Muhammed ibn Umail al-Tamimi

Ibn Umayl, Senior Zadith, Muhammed ibn Umail at-Tamîmî (Arabic: محمد بن أميل التميمي) was an alchemist of the tenth century. He can be dated to 900–960 AD (286-348 AH) on the basis of the names of acquaintances he mentioned.[1] About his life, since he lived in seclusion, very little is known.[2] Ibn Umayl may have been born in Spain of Arabic parents for a Vatican catalogue lists one manuscript with the nisba Andalusian[3] but his writings suggest he mostly lived and worked in Egypt. He also visited North Africa and Iraq.[1][4]

In later European literature ibn Umayl became known by a number of names, including Senior from the title Sheikh becoming 'senior' by translation into Latin, Senior Zadith from the honorific al-sadik becoming Zadith phonetically[5] and Zadith filius Hamuel, Zadith ben Hamuel or Zadith Hamuelis from an erroneous translation of ibn Umail.

Allegorical alchemist

Ibn Umayl is what is now called an allegorical alchemist. He saw himself as following his “predecessors among the sages of Islam” in rejecting alchemists who take their subject literally. Although such experimenters discovered the sciences of metallurgy and chemistry, Ibn Umayl felt the allegorical meaning of alchemy is the precious goal that is tragically overlooked. He wrote:

“Eggs are only used as an analogy... the philosophers … wrote many books on such things as eggs, hair, the biles, milk, semen, claws, salt, sulphur, iron, copper, silver, mercury, gold and all the various animals and plants … But then people would copy and circulate these books according to the apparent meaning of these things, and waste their possessions and ruin their souls” The Pure Pearl chap. 1.[1]

For all his devotion to Greek alchemy Ibn Umayl writes as a Muslim, frequently mentioning his religion, explaining his ideas "for all our brothers who are pious Muslims" and quoting verses from the Quran.[1]

The interpreter

Ibn Umail presented himself as an interpreter of mysterious symbols. He set his allegory Silvery Water in an Egyptian temple Sidr wa-Abu Sîr, the Prison of Yasuf, where Joseph learned how to interpret the dreams of the Pharaoh. (Koran: 12 Yusuf and Genesis: 4)

"... none of those people who are famous for their wisdom could explain a word of what the philosophers said. In their books they only continue using the same terms that we find in the sages .... What is necessary, if I am a sage to whom secrets have been revealed, and if I have learned the symbolic meanings, is that I explain the mysteries of the sages." [4][6]

The psychologist CG Jung recognized in ibn Umayl’s story the ability to bring self-realization to a soul by interpreting dreams, and from the 1940s onwards focused his work on alchemy.

Works Attributed to ibn Umail

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- Ḥall al-Rumūz (Solving the Riddles)

- al-Durra al-Naqīya (The Pure Pearl)

- Kitāb al-Maghnisīya (The Book of Magnesium)

- Kitāb Mafātīḥ al-Ḥikma al-‘Uẓmā (The Book of the Keys of the Greatest Wisdom)

- al-Mā’ al-Waraqî wa'l-Arḍ al-Najmīya (The Silvery Water and the Starry Earth) that comprises a narrative; a poem Risālat al-Shams ilā al-Hilâl (Epistola solis ad lunam crescentem, the letter of the Sun to the Crescent Moon),[7][8]

Later Publications

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- 12th century: al-Mā’ al-Waraqī (Silvery Water) became a classic of Islamic Alchemy. It was translated into Latin in the twelfth or thirteenth century and was widely disseminated among alchemists in Europe often called Senioris Zadith tabula chymica (The Chemical Tables of Senior Zadith)[7]

- 1339: In the al-Mâ’ al-Waraqī transcript that is now in Topkapi Palace Library, Istanbul, the scribe added a note to the diagram that the sun represents the spirit (al-rūḥ) and the moon the soul (al-nafs) so the "Letter from the Sun to the Moon" is about perfecting the receptivity of soul to spirit.[7]

- 14th century: Chaucer's Canon's Yeoman's Tale has alchemy as a theme and cites Chimica Senioris Zadith Tabula (The Chemical Tables of Senior Zadith). Chaucer considered Ibn Umayl to be a follower of Plato.

- 15th century: Aurora consurgens is a commentary by Pseudo Aquinas on a Latin translation of Al-mâ' al-waraqî (Silvery Water).

- 1605 Senioris Zadith filii Hamuelis tabula chymica (The Chemical Tables of Senior Zadith son of Hamuel) was printed as part I of Philosophiae Chymicae IV. Vetvstissima Scripta by Joannes Saur[9]

- 1660: The Chemical Tables of Senior Zadith retitled Senioris antiquissimi philosophi libellus was printed in volume 5 of the Theatrum chemicum.

- 1933 Three Arabic treatises on alchemy by Muhammad ibn Umail (10th century AD) translated from the Arabic by H.E. Stapleton and M.H. Husein. Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta.[4]

- 1997: Corpus Alchemicum Arabicum, a new translation of Hall ar-Rumuz with a commentary by the Jungian psychologist and scholar Marie-Louise von Franz[10]

Value to Scholars

The Silvery Water was particularly valuable to Stapleton,[4] Lewis and Sherwood Taylor, who showed that of some of Umail's ‘Sayings of Hermes’ came from Greek originals. Also its numerous quotations from earlier alchemical authors[2]:102 allowed, for example, Stapleton to provenance the Turba Philosophorum as being Arabic in origin,[2]:83 and Plessner to date the Turba ca. 900AD.[11]

Gallery

-

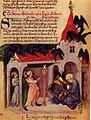

Ibn Umayl was depicted in later European books. In Aurora consurgens, c.1400, Here Senior Zadith carries the Key that opens The Treasure House of Wisdom.

-

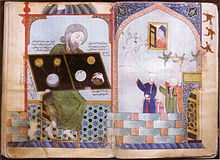

Aurora Consurgens also illustrates The Silvery Water description of an Egyptian temple statue of an ancient sage holding the tablet of wisdom.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Starr, Peter: Towards a Context for Ibn Umayl, Known to Chaucer as the Alchemist Senior. Retrieved 2013-05-22

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Holmyard, E.J. (1990) [1957]. Alchemy (reprint ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0486262987.

- ↑ Paul Kraus: Jâbir ibn Haiyân, Cairo, IFAO, 1942–3, p. 299.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Stapleton, H.E.; M.H. Husein (1933). Three Arabic treatises on Alchemy by Muhammad ibn Umail (10th century AD). Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- ↑ Julius Ruska, Senior Zadith = Ibn Umail. Orientalistische Literaturzeitung 31, 1928, pp. 665-666.

- ↑ Stapleton/Husein's seminal work was reprinted in facsimile in 2002 as Ibn Umayl (fl. c. 912). Texts and Studies (Collection "Natural Science in Islam", vols. nº 55-75). Ed. F. Sezgin. ISBN 3-8298-7081-7. Published by Institut für Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften, University of Frankfurt, Westendstrasse 89 , D-60325 Frankfurt am Main.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Berlekamp, Persis (2003). Murqarnas Volume 20: Painting as Persuasion, a visual defense of alchemy in an Islamic manuscript of the Mongol period. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 9004132074.

- ↑ Julius Ruska, Studien zu Muhammad Ibn Umail al-Tamimi's Kitab al-Ma' al-Waraqi wa'l-Ard an-Najmiyah, Isis, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Feb., 1936), pp. 310-342.

- ↑ Dickinson College Digital Collections Philosophiae Chymicae IV. Vetvstissima Scripta

- ↑ Von Franz, Marie-Louise (2007). Corpus Alchemicum Arabicum: Book of the Explanation of the Symbols Kitab Hall Ar-Rumuz, a Psychological Commentary. Switzerland: Daimon Verlag. ISBN 3952260835.

- ↑ Martin Plessner, The Place of the Turba Philosophorum in the Development of Alchem. ISIS, Vol. 45, No. 4, Dec. 1954, pp. 331-338

External links

- Chaucer Name Dictionary 1988, Jacqueline de Weever, Garland Publishing

- (French) Commentary on the Bibliotheca Chemica at item 86.

- Millesima, Julia (2011). "ibn Umail-Senior Zadith, Introduction to Tabula Chimica". Alchemy Key Concepts & the Art of Fire. Ancient Authors & Hidden Evidence. Labyrinth Designers. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||