Movable singularity

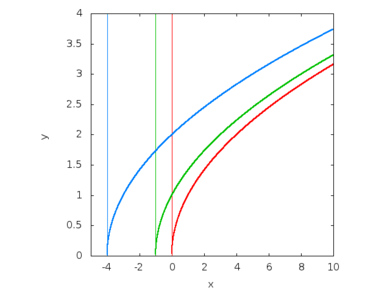

subject to the initial conditions y(0)=0, 1 and 2 (red, green and blue curves respectively). The positions of the moving singularity at x= 0, -1 and -4 is indicated by the vertical lines.

subject to the initial conditions y(0)=0, 1 and 2 (red, green and blue curves respectively). The positions of the moving singularity at x= 0, -1 and -4 is indicated by the vertical lines.In the theory of ordinary differential equations, a movable singularity is a point where the solution of the equation behaves badly and which is "movable" in the sense that its location depends on the initial conditions of the differential equation.[1] Suppose we have an ordinary differential equation in the complex domain. Any given solution y(x) of this equation may well have singularities at various points (i.e. points at which it is not a regular holomorphic function, such as branch points, essential singularities or poles). A singular point is said to be movable if its location depends on the particular solution we have chosen, rather than being fixed by the equation itself.

For example the equation

has solution  for any constant c. This solution has a branchpoint at

for any constant c. This solution has a branchpoint at  , and so the equation has a movable branchpoint (since it depends on the choice of the solution, i.e. the choice of the constant c).

, and so the equation has a movable branchpoint (since it depends on the choice of the solution, i.e. the choice of the constant c).

It is a basic feature of linear ordinary differential equations that singularities of solutions occur only at singularities of the equation, and so linear equations do not have movable singularities.

When attempting to look for 'good' nonlinear differential equations it is this property of linear equations that one would like to see: asking for no movable singularities is often too stringent, instead one often asks for the so-called Painlevé property: 'any movable singularity should be a pole', first used by Sofia Kovalevskaya.

References

- ↑ Bender, Carl M.; Orszag, Steven A. (1999). Advanced Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers: Asymptotic Methods and Perturbation Series. Springer. p. 7.

- Einar Hille (1997), Ordinary Differential Equations in the Complex Domain, Dover. ISBN 0-486-69620-0