Motivation crowding theory

Motivation crowding theory, in labor economics and social psychology, suggests that extrinsic motivators such as monetary incentives or punishments can undermine (or, under different conditions, strengthen) intrinsic motivation.[1] For example, if the imposition of a fine or other concrete penalty results in an increase of a prohibited behavior, the penalty is said to "crowd out" the intrinsic social disincentive by associating violations with a more psychologically acceptable cost.[2] Tangible incentives crowding out intrinsic motivation is known as the overjustification effect. Similarly, the Yerkes–Dodson law describes physiological or mental arousal first strengthening and then crowding out productivity over short time scales.

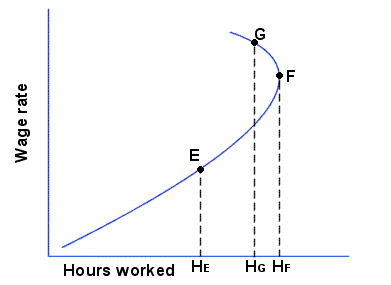

The theory contrasts with the relative price effect on which mainstream economics is based.[1] In neoclassical labor microeconomics, when the supply of labor is decided by the worker, such as in volunteer or paid voluntary labor, the amount of work performed is often described by the backward bending supply curve of labour. The curve indicates that while workers will initially chose to work more when paid more per hour, there is a point after which rational workers will choose to work less, as the marginal value of more money is outweighed by the loss of available time. Since the vertical axis only represents extrinsic compensation, the curve does not represent a complete description of voluntary labor.

Researchers are interested in understanding the conditions which maximize motivation and productivity.[1] Recent studies and literature reviews suggest that as managers have become more aware of the conditions involved in influencing overall motivation, external incentives for volunteers and laborers have not led to decreases in intrinsic motivation or output productivity.[3][4][5][6][7] Those results are consistent with an earlier meta-analysis that found intrinsic motivation is only diminished by tangible rewards when they are both expected and given simply for doing a task, and then those rewards are removed, instead of given for achieving the task's goals, or given unexpectedly.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Frey, B.S. and Jegen, R. (2001) "Motivation Crowding Theory" Journal of Economic Surveys 15(5):589–611

- ↑ Levitt, S.D. and Dubner, S.J. (2005) Freakonomics, Chapter 1

- ↑ Fang, M. and Gerhart, B. (June 2011) "Does pay for performance diminish intrinsic interest?" International Journal of Human Resource Management

- ↑ Thompson, G.D., et al. (2010) "Does Paying Referees Expedite Reviews? Results of a Natural Experiment" Economic Journal 76(3):678–92

- ↑ Fiorillo, D. (2011) "Do monetary rewards crowd out intrinsic motivations of volunteers? Some empirical evidence for Italian volunteers" Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 82(2):139–65

- ↑ Eisenberger, R. et al. (1999) "Does pay for performance increase or decrease perceived self-determination and intrinsic motivation?" Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77(5):1026–40

- ↑ Reitman, D. (1998) "The real and imagined harmful effects of rewards: implications for clinical practice" Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 29(2):101–13 PMID 9762587

- ↑ Cameron, J. and Pierce, W.D. (1994) "Reinforcement, Reward, and Intrinsic Motivation: A Meta-Analysis" Review of Educational Research 64(3):363–423