Mosul

Coordinates: 36°20′N 43°08′E / 36.34°N 43.13°E

| Mosul الموصل | |

|---|---|

|

Tigris River and bridge in Mosul | |

Mosul | |

| Coordinates: 36°20′N 43°08′E / 36.34°N 43.13°E | |

| Country |

|

| Province | Nineveh Governorate |

| Elevation[1] | 223 m (732 ft) |

| Population (2008) | |

| • Urban | 1,800,000 |

| Time zone | GMT +3 |

Mosul (/moʊˈsuːl/; Arabic: الموصل al-Mawṣil; Kurdish: مووسڵ Mûsil; North Mesopotamian Arabic: el-Mōṣul; Ottoman Turkish: موصل Musul; Syriac: ܢܝܢܘܐ Nînwe,Turkish: Musul), is a city of over a million people in northern Iraq, some 400 km north of Baghdad. It is currently the largest city controlled by the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant. The original city stands on the west bank of the Tigris River, opposite the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh on the east bank, but the metropolitan area has now grown to encompass substantial areas on both banks.

In the early 21st century, the majority of its population was Arab, with Assyrian, Iraqi Turkmen and Kurdish minorities. The city's population grew rapidly around the turn of the millennium and by 2008 was estimated to be 1,800,000.[2] Although half a million fled in 2014[3] it was still over a million that year. With the 2014 occupation by the terror organization ISIL, only Sunni Arabs remained in the city.

Historically important product of the area is Mosul marble. People from Mosul are called Maslawis. The city of Mosul was home to the University of Mosul, which was one of the largest educational and research centers in Iraq and the Middle East. Until 2014 the city was a historic center for the Nestorian Christianity of the Assyrians, containing the tombs of several Old Testament prophets such as Jonah.

In June 2014, the terror organization ISIL took over the city during the 2014 Northern Iraq offensive.[4][5][6] As of August 2014, the city's new ISIL administration is functional, but power cuts are frequent.[7]

Etymology

The name of the city is first mentioned by Xenophon in 401 BC in his expeditionary logs. There, he notes a small town of "Mépsila" (Ancient Greek: Μέψιλα) on the Tigris somewhere about where modern Mosul is today (Anabasis, III.iv.10). It may be safer to identify Xenophon's Mépsila with the site of Iski Mosul, or "Old Mosul", 20 miles north of modern Mosul, where six centuries after Xenophon's report, the Sasanian Persian center of Budh-Ardhashīr was built. Be that as it may, the name Mepsila is doubtlessly the root for the modern name.

Nineveh gave its place to Mepsila after its violent fall to the Babylonians, Medes, and the Iranic Sagartians in 612 BCE. In fact, Xenophon makes no mention of it in his expedition of 401 BC (during the reign of the Persian Achaemenid dynasty in this region), although he does note Mepsila.

In its current Islamic form and spelling, the term Mosul, or rather "Mawsil" stands for the "linking point" – or loosely, the Junction City, in Arabic. Mosul should not be confused with the ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh which is located across the Tigris from Mosul on the eastern banks, at the famed archaeological mound of Kuyunjik (Turkoman for "sheep's hill"). This area is better known today as the town of Nebi Yunus ("prophet Jonah") and almost entirely populated by Kurds, which makes it the only fully-Kurdish neighborhood in Mosul. The site contains the tomb of the Biblical Jonah as he lived and died in Nineveh, then the capital of ancient Assyria. Today, this entire area has been absorbed into Mosul metropolitan area. The surviving Assyrians refer to the entire city of Mosul as Nineveh (or rather, Ninweh).

It is also named al-Faiha ("the Paradise"), al-Khaḍrah ("the Green") and al-Hadbah ("the Humped"). It is sometimes described as "The Pearl of the North"[8] and "the city of a million soldiers."[9]

The demonym for inhabitants of Mosul is "Moslawi."

History

Ancient era and early Middle Ages

The Bible says that Nineveh was founded by Nimrod, son of Cush.[10]

In approximately 850 BCE, King Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria chose the city of Nimrud as his capital, 30 kilometres from present day Mosul. In approximately 700 BC, King Sennacherib made Nineveh the new capital of Assyria. The mound of Kuyunjik in Mosul is the site of the palaces of King Sennacherib and his grandson Ashurbanipal, who established the Library of Ashurbanipal.

Mosul later succeeded Nineveh as the Tigris bridgehead of the road that linked Syria and Anatolia with the Median Empire. In 612 BC, the Mede emperor Cyaxares the Great, together with the alliance of Nabopolassar king of Babylon and the Sagartians, conquered Nineveh.

It became part of the Seleucid Empire after Alexander's conquests in 332 BCE. While little is known of the city from the Hellenistic period, Mosul likely belonged to the Seleucid satrapy of Mesopotamia, which was conquered by the Parthian Empire in a series of wars that ended in 129 BC with the victory of Phraates II defeat of the Seleucid king Antiochus VII.

The city changed hands once again with the rise of Sassanid Persia in 225 CE. Christianity was present among the indigenous Assyrian people in Mosul as early as the 2nd century. It became an episcopal seat of the Nestorian faith in the 6th century. In 637 (other sources say 641), during the period of the Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab, the city was annexed to the Rashidun Caliphate by Utba bin Farqad Al-Salami.

Mosul was promoted to the status of capital of Mesopotamia under the Umayyads in the 8th century, during which it reached a peak of prosperity. During the Abbassid era it was an important trading centre because of its strategic location astride the trade routes to India, Persia, and the Mediterranean. The Muslim general and conqueror of Sindh, Muhammad bin Qasim, is said to have died here in the 8th century AD.

9th century to 1535

.jpeg)

In the late 9th century control over the city was seized by the Turkish dynasts Ishaq ibn Kundajiq and his son Muhammad, but in 893 Mosul came once again under the direct control of the Abbasid Caliphate. In the early 10th century Mosul came under the control of the native Arab Hamdanid dynasty. From Mosul, the Hamdanids under Abdallah ibn Hamdan and his son Nasir al-Dawla expanded their control over the Jazira for several decades, first as governors of the Abbassids and later as de facto independent rulers. A century later they were supplanted by the Uqaylids.

Mosul was conquered by the Seljuks in the 11th century. After a period under semi-independent atabeg such as Mawdud, in 1127 it became the centre of power of the Zengid dynasty. Saladin besieged the city unsuccessfully in 1182 but finally gained control of it in 1186. In the 13th century it was captured by the Mongols led by Hulegu, but was spared the usual destruction since its governor, Badr al-Din Luʾluʾ, helped the Khan in his following campaigns in Syria. After the Mongol defeat in the Battle of Ain Jalut against the Mamluks, Badr al-Din's son sided with the latter; this led to the destruction of the city, which later regained some importance but never recovered its original splendor. Mosul was thenceforth ruled by the Mongol Ilkhanid and Jalayrid dynasties, and escaped Tamerlan's destructions.

During 1165 Benjamin of Tudela passed through Mosul;[11] in his papers he wrote that he found a small Jewish community estimated as 7000 people in Mosul, the community was led by rebbi Zakhi (זכאי) presumably connected to the King David dynasty. In 1288–1289, the Exilarch was in Mosul and signed a supporting paper for Maimonides.[11][12] In the early 16th century Mosul was under the Turkmen federation of the Ak Koyunlu, but in 1508 it was conquered by the Persian Safawids.

Ottomans: 1535 to 1918

In 1535, Ottoman Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent added Mosul to his empire. Thenceforth Mosul was governed by a pasha. Mosul was celebrated for its line of walls, comprising seven gates with large towers, a renowned hospital (maristan) and a covered market (qaysariyya), and was also famous for its fabrics and flourishing trades.

Although Mesopotamia had technically been integrated within the Ottoman Empire since 1533, until the reconquest of Baghdad in 1638 the city of Mosul was considered “still a mere fortress, important for its strategic position as an offensive platform for Ottoman campaigns into Iraq, as well as a defensive stronghold and (staging post) guarding the approaches to Anatolia and to the Syrian coast. Then with the Ottoman reconquest of Baghdad, the liwa’ of Mosul became an independent wilaya.”[13]:202

Despite being a part of the Ottoman Empire, during the four centuries of Ottoman rule Mosul was considered “the most independent district” within the Middle East, following the Roman model of indirect rule through local notables.[14]:203–4 “Mosuli culture developed less along Ottoman-Turkish lines than along Iraqi-Arab lines; and Turkish, the official language of the State, was certainly not the dominant language in the province.”[13]:203

In line with its status as a politically stable trade route between the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf the city developed considerably during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Similar to the development of the Mamluk dynasty in Baghdad, during this time “the Jalili family was establishing itself as the undisputed master of Mosul”, and “helping to connect Mosul with a pre-Ottoman, pre-Turcoman, pre-Mongol, Arab cultural heritage which was to put the town on its way to recapturing some of the prestige and prominence it had enjoyed under the golden reign of Badr ad-Din Lu’lu’.”[13]:203

Along with the al-Umari and Tasin al-Mufti families, the Jalilis formed an “urban-based small and medium gentry and a new landed elite”, which proceeded to displace the control of previous rural tribes.[15] Such families proceed to establish themselves through private enterprise, solidifying their influence and assets through rents on land and taxes on urban and rural manufacturing.

As well as elected officials, the social architecture of Mosul was highly influenced by the Dominican fathers who arrived in Mosul in 1750, sent by Pope Benedict XIV (Mosul had a large Christian population, predominantly Assyrians).[16] They were followed by the Dominican nuns in 1873. They established a number of schools, health clinics, a printing press and an orphanage. The nuns also established workshops to teach girls sewing and embroidery.[17] A congregation of Dominican sisters, founded in the 19th century, still had its motherhouse in Mosul by the early 21st century. Over 120 Assyrian Iraqi Sisters belonged to this congregation.[16]

In the nineteenth century the Ottoman government started to reclaim central control over its outlying provinces. Their aim was to “restore Ottoman law, and rejuvenate the military” as well as reviving “a secure tax base for the government”.[18]:24–6 In order to reestablish rule in 1834 the Sultan abolished public elections for the position of governor, and began “neutraliz[ing] local families such as the Jalilis and their class.”[18]:28–29 and appointing new, non-Maslawi governors directly. In line with its reintegration within central government rule, Mosul was required to conform to new Ottoman reform legislation, including the standardization of tariff rates, the consolidation of internal taxes and the integration of the administrative apparatus with the central government.[18]:26

This process started in 1834 with the appointment of Bayraktar Mehmet Pasha, who was to rule Mosul for the next four years. After the reign of Bayraktar Mehmet Pasha, the Ottoman government (wishing still to restrain the influence of powerful local families) appointed a series of governors in rapid succession, ruling “for only a brief period before being sent somewhere else to govern, making it impossible for any of them to achieve a substantial local power base.”[18]:29 Mosul's importance as a trading center declined after the opening of the Suez canal, which enabled goods to travel to and from India by sea rather than by land across Iraq and through Mosul.

Mosul remained under Ottoman control until 1918 when it was taken by the British, with a brief break in 1623 when Persia seized the city, and was the capital of Mosul Vilayet one of the three vilayets (provinces) of Ottoman Iraq.

1918 to 2003

In 1916 a secret agreement was made between the French and the British governments, known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement. It was to draw a straight line from the Jordan heights to Iran: where the northern zone (Syria, and Mount Lebanon) would be under French influence, and the southern zone (Mesopotamia, and later, after re-negotiations in 1917, Palestine, which initially was planned to include Transjordan) would be under British military control. Mosul was in the northern zone, and would have become a French-controlled city; but early discoveries of oil in the region, just before the end of the war in 1918, pushed the British government to yet another negotiation with the French; to include the region of Mosul into the southern (British) zone.

At the end of World War I in October 1918, after the signature of the Armistice of Mudros, British forces occupied Mosul. After the war, the city and the surrounding area became part of the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration (1918-1920), and shortly Mandatory Iraq (1920-1932). This mandate was contested by Turkey which continued to claim the area based on the fact that it was under Ottoman control during the signature of the Armistice. In the Treaty of Lausanne, the dispute over Mosul was left for future resolution by the League of Nations. Iraq's possession of Mosul was confirmed by the League of Nations brokered agreement between Turkey and Great Britain in 1926. Former Ottoman Mosul Vilayet eventually became Nineveh Province of Iraq, but Mosul remained the provincial capital.

The city's fortunes revived with the discovery of oil in the area, from the late 1920s onward. It became a nexus for the movement of oil via truck and pipeline to both Turkey and Syria. Qyuarrah Refinery was built within about an hour's drive from the city and was used to process tar for road-building projects. It was damaged but not destroyed during the Iran–Iraq War.

The opening of the University of Mosul in 1967 enabled the education of many in the city and surrounding areas.

After the 1991 uprisings by the Kurds Mosul did not fall within the Kurdish-ruled area, but it was included in the northern no-fly zone imposed and patrolled by the United States and Britain between 1991 and 2003.

Although this prevented Saddam's forces from mounting large-scale military operations again in the region, it did not stop the regime from implementing a steady policy of "Arabisation" by which the demography of some areas of Nineveh Governorate were gradually changed. Despite the program Mosul and its surrounding villages remained home to a mixture of Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians, Armenians, Turkmens, a few Jews, and isolated populations of Yazidis and Mandeans. Saddam was able to garrison portions of the 5th Army within the city of Mosul, had Mosul International Airport under military control, and recruited heavily from the city for his military's officer corps; this may have been due to the fact that most of the officers and generals of the Iraqi Army were from Mosul long before the Saddam regime era.

2003 to 2014

When the 2003 invasion of Iraq was being planned, the United States had originally intended to base troops in Turkey and mount a thrust into northern Iraq to capture Mosul. However, the Turkish parliament refused to grant permission for the operation. When the Iraq War did break out in March 2003, US military activity in the area was confined to strategic bombing with airdropped special forces operating in the vicinity. Mosul fell on April 11, 2003, when the Iraqi Army 5th Corps, loyal to Saddam, abandoned the city and eventually surrendered, two days after the fall of Baghdad. US Army Special Forces with Kurdish fighters quickly took civil control of the city. Thereafter began widespread looting before an agreement was reached to cede overall control to US forces.

On July 22, 2003, Saddam Hussein's sons, Uday Hussein and Qusay Hussein, were killed in a gunbattle with Coalition forces in Mosul after a failed attempt at their apprehension.[19] The city also served as the operational base for the US Army's 101st Airborne Division during the occupational phase of the Operation Iraqi Freedom. During its tenure, the 101st Airborne Division was able to extensively survey the city and, advised by the 431st Civil Affairs Battalion, non-governmental organizations, and the people of Mosul, began reconstruction work by employing the people of Mosul in the areas of security, electricity, local governance, drinking water, wastewater, trash disposal, roads, bridges, and environmental concerns.[20] Other US Army units to have occupied the city include the 4th Brigade Combat Team of the 1st Cavalry Division, the 172nd Stryker Brigade, the 3rd Brigade-2nd Infantry Division, 18th Engineer Brigade (Combat), the 1st Brigade-25th Infantry Division, the 511th Military Police Company, the 812th Military Police Company and company-size units from Reserve components, an element of the 364th Civil Affairs Brigade, and the 404th Civil Affairs Battalion which covered the areas north of the Green Line.

On June 24, 2004, a coordinated series of car-bombs killed 62 people, many of them policemen.

In November 2004, concurrently with the US and Iraqi attack on the city of Fallujah, the Battle of Mosul (2004) began. On November 10, insurgents conducted coordinated attacks on the police stations. The policemen who were not killed in the fighting fled the city, leaving Mosul without any civil police force for about a month. However, soon after the insurgents' campaign to overrun the city had begun, elements from the 25th Infantry Division and components from the Multinational force composed mainly of Albanian forces, took the offensive and began to maneuver into the most dangerous parts of the city. Fighting continued well into the 11th with the insurgents on the defensive and US forces scouring neighborhoods for any resistance.

After November 2004, the city of Mosul suffered tremendously due to deteriorated security conditions (including military actions as well as threats and killing of innocent civilians by insurgents and criminals), unprecedented violence levels (especially on an ethnic basis), continuous destruction of the main infrastructures of the city, and neglect and mismanagement by the occupation forces, by the Nineveh Governorate Council, by multiple political parties as well as by the central Iraqi Government in Baghdad.

On December 21, 2004, fourteen US soldiers, four American employees of Halliburton, and four Iraqi soldiers were killed in a suicide attack on a dining hall at the Forward Operating Base (FOB) Marez next to the main US military airfield at Mosul. The Pentagon reported that 72 other personnel were injured in the attack carried out by a suicide bomber wearing an explosive vest and the uniform of the Iraqi security services. The Islamist group Army of Ansar al-Sunna (partly evolved from Ansar al-Islam) declared responsibility for the attack in an Internet statement.

In early 2005, the head of Mosul's anti-corruption unit, Gen. Waleed Kashmoula, was killed by a bomb which exploded outside his office. In October 2005, the Iraq Interior Department attempted to fire the police chief of Mosul. Mosul Sunni leaders saw it as a Kurdish attempt to seize control over the police. In the end the police chief was replaced by a Sunni Arab, MG Wathiq Al Hamdani, who was a city resident.

In December 2007, Iraq reopened Mosul International Airport. An Iraqi Airways flight carried 152 Hajj pilgrims to Baghdad, the first commercial flight since US forces declared a no-fly zone in 1993, although further commercial flight remained prohibited.[21] On January 23, 2008, an explosion in an apartment building killed 36 people. The following day, a suicide bomber dressed as a police officer assassinated the local police chief, Brig. Gen. Salah Mohammed al-Jubouri, the director of police for Ninevah province, as he toured the site of the blast.[22]

In May 2008, a military offensive of the Ninawa campaign was launched by US-backed Iraqi Army Forces led by Maj. Gen. Riyadh Jalal Tawfiq, the commander of military operations in Mosul, in the hope of bringing back stability and security to the city.[23] Though the representatives of Mosul in the Iraqi Parliament, the intellectuals of the city, and other concerned humanitarian groups agreed on the pressing need for a solution to the unbearable conditions of the city, they still believed that the solution was merely political and administrative. They also questioned whether such a large scale military offensive would spare the lives of innocent people.[24]

All these factors deprived the city of its historical, scientific, and intellectual foundations in the last 4 years, when many scientists, professors, academics, doctors, health professionals, engineers, lawyers, journalists, religious clergy (both Muslims and Christians), historians, as well as professionals and artists in all walks of life, were either killed or forced to leave the city under the threat of being shot, exactly as happened elsewhere in Iraq in the years following 2003.[25][26][27][28]

In 2008, many Assyrian Christians (about 12,000) fled the city following a wave of murders and threats against their community. The murder of a dozen Assyrians, threats that others would be murdered unless they converted to Islam and the destruction of their houses sparked a rapid exodus of the Christian population. Some families crossed the borders to Syria and Turkey while others were given shelter in churches and monasteries. Accusations were exchanged between Sunni fundamentalists and some Kurdish groups for being behind this new exodus. For the time being the motivation of these acts is unclear, but some claims linked it to the imminent provincial elections which took place in January 2009, and the related Assyrian Christians' demands for broader representation in the provincial councils.[29][30]

An investigation in 2009 pointed out that more than 2,500 Kurds had been killed and more than 40 families displaced in Mosul since 2003. The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan blamed Al-Qaeda and former Ba'ath Party members.

Occupation by ISIL

On June 10, 2014, Mosul was occupied by Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).[31][32] Troop shortages and infighting among top officers and Iraqi political leaders played into Islamic State's hands and fueled panic that led to the city's abandonment.[33] Kurdish intelligence had been warned by a reliable source in early 2014 that Mosul would be attacked by ISIL and ex-Baathists (and had informed the US and UK)[34] however Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and the Defence Minister turned down repeated offers of help from the Peshmerga. Half a million people escaped on foot or by car in the next 2 days.[35] ISIL acquired three divisions' worth of up-to-date American arms and munitions - including M1129 Stryker 120-mm mortars and at least 700 armoured Humvee vehicles from the then fleeing, or since massacred, Iraqi army.[36] Many residents initially welcomed ISIL[37] and according to a member of the UK Defence Select Committee Mosul "fell because the people living there were fed up with the sectarianism of the Shia dominated Iraqi government."[36]

2015

On 21 January 2015, the US began coordinating airstrikes with a Kurdish launched offensive, to help them begin the planned operation to retake the city of Mosul.[38]

Women

Women be accompanied by a male guardian.[35][39]

Persecution of religious and ethnic minorities and destruction of cultural sites

ISIL issued an edict expelling the remaining Christian Mosul citizens, after the Christians failed to attend a meeting to discuss their future status. According to Duraid Hikmat an expert on minority relationships and resident of Mosul the Christians were fearful to attend.[40] Emboldened ISIL authorities systematically destroyed Abrahamic cultural artifacts such as the cross from St. Ephrem's Cathedral, the tomb of Jonah, and a statue of the Virgin Mary. ISIL militants destroyed and pillaged the Tomb of Seth in Mosul. Artifacts within the tomb were removed to an unknown location.[41]

Students from Muslim minorities have been abducted.[3]

According to a UN report ISIL forces are persecuting ethnic groups near Mosul. The Yazidis and Shabaks are victims of killings and kidnappings and the destruction of their cultural sites.[40]

- Mosque of the Prophet Yunus or Younis (Jonah): On one of the two most prominent mounds of Nineveh ruins, used to rise the Mosque (a Nestorian-Assyrian Church year) of Prophet Younis "Biblical Jonah". Jonah the son of Amittai, from the 8th century BC, is believed to be buried here, where King Esarhaddon had once built a palace. It was one of the most important mosques in Mosul and one of the few historic mosques that are found on the east side of the city. On July 24, 2014, the building was destroyed by explosives set by forces of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.[42]

- Mosque of the Prophet Jerjis (Georges): The mosque is believed to be the burial place of Prophet Jerjis. Built of marble with shen reliefs and renovated last in 1393 AD it was mentioned by the explorer Ibn Jubair in the 12th century AD, and is believed also to embrace the tomb of Al-Hur bin Yousif.

- Mashad Yahya Abul Kassem: Built in the 13th century it was on the right bank of the Tigris and was known for its conical dome, decorative brickwork and calligraphy engraved in Mosul blue marble.

- Mosul library: Including the Sunni Muslim library, the library of the 265-year-old Latin Church and Monastery of the Dominican Fathers and the Mosul Museum Library. Among the 112,709 books and manuscripts thought lost are a collection of Iraqi newspapers dating from the early 20th century, as well as maps, books and collections from the Ottoman period; some were registered on a UNESCO rarities list. The library was ransacked and destroyed by explosives on 25 February 2015.[43]

- Mosul Museum and Nirgal Gate: Statues and artefacts that date from the Assyrian and Akkadian empires, including artefacts from sites including the Assyrian cities of Nineveh and Nimrud and the Greco-Roman site of Hatra.[44][45]

Their plans for uprising were accelerated when ISIL scheduled the destruction of the al-Ḥadbā[46] Many former supporters of ISIL's Caliphate have voiced protest against ISIL online in the aftermath of destruction of ancient cultural sites.

Detention of diplomats

Turkish diplomats and consular staff were detained for over 100 days.[47]

Human Rights

Scores of people have been executed without fair trial.[48][49]

Armed opposition

The urban guerrilla warfare groups may be called the Nabi Yunus Brigade after the Nabi Yunus mosque, or the Kataeb al-Mosul (Mosul Brigade).[50] The brigade claims to have killed ISIL members with sniper fire.[51]

Demography

.jpg)

During the 20th century, Mosul city had been indicative of the mingling ethnic and religious cultures of Iraq. There used to be a Sunni Arab majority in urban areas, such as downtown Mosul on the Tigris; across the Tigris and further north in the suburban areas, thousands of Assyrians, Kurds, Turkmens, Shabaks and Armenians made up the rest of Mosul's population.[52] Shabaks were concentrated on the eastern outskirts of the city.

Arabization plans in the 1980s by former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein and his Ba'ath party forced some of those minorities to move outside the city, back into nearby Kurdish regions of Iraq. With the Islamic State occupation in 2014, only Sunni Arabs remained in the city. The total population of Mosul dropped to about one million from previous 1.5 million.

Religion

The majority of people in Mosul are Sunni Muslims. Most people of other religions, including Assyrian Christians and Shiite Muslims, were driven out by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Despite institutional ethnic persecution by various political powers, including the Ba'ath Party regime, Mosul maintained a multicultural and multi-religious mosaic until ISIL took over. The difficult history of Mosul, however, still contributed to tensions among its modern inhabitants.

Mosul had a community of Assyrian Christians who also had a presence in the villages around Mosul in ancient Nineveh since the foundation of the city (majority follow the Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church, and a minority follow the Assyrian Church of the East). There were also a number of Arab Christians belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, the Chaldean Catholic Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church, and a number of Protestant churches. Long before the Muslim conquest of the seventh century, the old city of Nineveh was Christianized when the Assyrians converted to Christianity during the first and second centuries.

Other religions, such as Yazidi, Yarsan and Mandean religions also called Mosul home.[53][54]

Mosul had a Jewish population. Like their counterparts elsewhere in Iraq, most left in 1950–51. Most Iraqi Jews have moved to Israel, and some to the United States.[55] A rabbi in the American army found an abandoned, dilapidated synagogue in Mosul dating back to the 13th century.[56]

Language

The Arabic of Mosul is considered to be much softer in its pronunciation than that of Baghdad Arabic, bearing considerable resemblance to Levantine dialects, particularly Aleppan Arabic.

Mosul Arabic is influenced largely by the languages of every ethnic minority group co-existing in the city: Kurds, Turkmen, Armenians, Assyrians, as well as others – thus infusing Kurmanji Kurdish, Turkmen, Armenian, and Neo-Aramaic. Each minority language is respectively spoken alongside North Mesopotamian Arabic.

North Mesopotamian Arabic is the lingua franca of communication, education, business, and official work to the majority of the city's residents. Upper class and university-educated residents usually have varying degrees of proficiency in English as well.

Government

There are sometimes impromptu checkpoints. Beginning in 2014, there were public executions held by ISIL.[57]

Plans to recapture

Between Summer 2014 and January 2015, the Iraqi government was planning to retake the city with the help of the peshmerga, Sunni tribes and US-led coalition air support.[58] On 21 January 2015, the Kurdish Peshmerga, aided by US airstrikes, began the planned operation.

Economy

Inflation and unemployment are high.[59]

Infrastructure

Water supply cuts are common[60] and mobile phone networks have been shut down.[57]

The city is served by Mosul International Airport, which hosts three airlines but had all services suspended after ISIL took over the city during 2014.

Climate

Mosul experiences a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh) with extremely hot, almost rainless summers and cool, rainy winters. Mosul, although not at a particularly high elevation, still receives much more rain than most of Iraq. Rainfall is close to three times that of Baghdad and over twice that of Basra, despite being much further from the Persian Gulf than either. It is in fact adequate for rain-fed cropping of wheat and barley. The Kurdish regions to the north are even wetter.

Snow fell on 23 February 2004,[61] 9 February 2005[62] and 10 January 2013.[63]

| Climate data for Mosul | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.1 (70) |

26.9 (80.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

35.5 (95.9) |

42.9 (109.2) |

44.1 (111.4) |

47.8 (118) |

49.3 (120.7) |

46.1 (115) |

42.2 (108) |

32.5 (90.5) |

25.0 (77) |

49.3 (120.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.4 (54.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

39.2 (102.6) |

42.9 (109.2) |

42.6 (108.7) |

38.2 (100.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

21.1 (70) |

14.1 (57.4) |

27.76 (81.98) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.0 (77) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.2 (45) |

3.8 (38.8) |

12.83 (55.09) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.6 (0.3) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

8.9 (48) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−6.1 (21) |

−15.4 (4.3) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 62.1 (2.445) |

62.7 (2.469) |

63.2 (2.488) |

44.1 (1.736) |

15.2 (0.598) |

1.1 (0.043) |

0.2 (0.008) |

0.0 (0) |

0.3 (0.012) |

11.8 (0.465) |

45.0 (1.772) |

57.9 (2.28) |

363.6 (14.316) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 11 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 71 |

| Source #1: World Meteorological Organisation (UN)[64] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weatherbase (extremes only)[65] | |||||||||||||

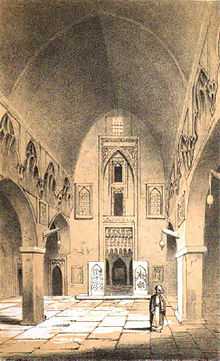

Historical and religious buildings

Mosul is rich in old historical places and ancient buildings: mosques, castles, churches, monasteries, and schools, many of which have architectural features and decorative work of significance. The town center is dominated by a maze of streets and attractive 19th-century houses. There are old houses here of beauty. The markets are particularly interesting not simply for themselves alone but for the mixture of people who jostle there: Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians, Iraqi Jews, Kurdish Jews, Iraqi Turkmens, Armenians, Yazidi, Mandeans, Romani and Shabaks.

The Mosul Museum contains many interesting finds from the ancient sites of the old Assyrian capital cities Nineveh and Nimrud. The Mosul Museum is a beautiful old building, around a courtyard and with an impressive facade of Mosul marble containing displays of Mosul life depicted in tableau form. Recently, On February 26, 2015, ISIS militants destroyed the ancient Assyrian artifacts of the museum.

The famous English writer, Agatha Christie, lived in Mosul whilst her second husband, an archaeologist, was involved in the excavation in Nimrud.

- Bash Tapia Castle: Mosul's old walls have disappeared, with the exception of these imposing ruins rising high over the Tigris.

- Qara Serai (The Black Palace): The remnants of the 13th-century palace of Sultan Badruddin Lu'lu'.

Mosques and shrines

- Umayyad Mosque: The first ever in the city, built in 640 AD by Utba bin Farqad Al-Salami after he conquered Mosul in the reign of Caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab. The only original part still extant is the remarkably elaborate brickwork 52m high minaret that leans like the Tower of Pisa, called Al-Hadba (The Humped).

- The Great (Nuriddin) Mosque: Built by Nuriddin Zangi in 1172 AD next door to the Umayyad Mosque. Ibn Battuta (the great Moroccan traveller) found a marble fountain there and a mihrab (the niche that indicates the direction of Mecca) with a Kufic inscription.

- Mujahidi Mosque: The mosque dates back to 12th century AD, and is distinguished for its shen dome and elaborately wrought mihrab.

- Prophet Younis Mosque and Shrine: Located east of the city, and included the tomb of Prophet Younis (Jonah), dating back to the 8th century BC, with a tooth of the whale that swallowed and later released him. It was completely annihilated by ISIS in July 2014.[66]

- Prophet Jirjis Mosque and Shrine: The late 14th century mosque and shrine honoring Prophet Jirjis (George) was built over the Quraysh cemetery. It was destroyed by ISIS in July 2014.[67]

- Prophet Daniel Shrine: A Tomb attricuted to Prophet Daniel was destroyed by ISIS in July 2014.[68][69]

- Hamou Qado (Hema Kado) Mosque: An Ottoman-era mosque in the central Maydan area built in 1881, and officially named Mosque of Abdulla Ibn Chalabi Ibn Abdul-Qadi.[70] It was destroyed by ISIS in March 2015 because it contained a tomb that was revered and visited by local Muslims on Thursdays and Fridays.[71]

Churches and monasteries

Mosul had the highest proportion of Assyrian Christians of all the Iraqi cities outside of the Kurdish region, and contains several interesting old churches, some of which originally date back to the early centuries of Christianity. Its ancient Assyrian churches are often hidden and their entrances in thick walls are not easy to find. Some of them have suffered from overmuch restoration.

- Shamoun Al-Safa (St. Peter, Mar Petros): This church dates from the 13th century is and named after Shamoun Al-Safa or St. Peter (Mar Petros in Assyrian Aramaic). Earlier it had the name of the two Apostles, Peter and Paul, and was inhabited by the nuns of the Sacred Hearts.

- Church of St. Thomas (Mar Touma in Assyrian Aramaic): One of the oldest historical churches, named after St. Thomas the Apostle who preached the Gospel in the East, including India. The exact time of its foundation is unknown, but it was before 770 AD, since Al-Mahdi, the Abbasid Caliph, is mentioned as listening to a grievance concerning this church on his trip to Mosul.

- Mar Petion Church: Mar Petion, educated by his cousin in a monastery, was martyred in 446 AD. It is the first Chaldean Catholic church in Mosul, after the union of many Assyrians with Rome in the 17th century. It dates back to the 10th century, and lies 3 m below street level. This church suffered destruction, and it has been reconstructed many times. A hall was built on one of its three parts in 1942. As a result, most of its artistic features have been messed up.

- Ancient Tahira Church (The Immaculate): Near Bash Tapia, considered one of the most ancient churches in Mosul. No evidence helps to determine its exact area. It could be either the remnants of the church of the Upper Monastery or the ruined Mar Zena Church. Al-Tahira Church dates back to the 7th century, and it lies 3 m below street level. Reconstructed last in 1743.

- Mar Hudeni Church: It was named after Mar Ahudemmeh (Hudeni) Maphrian of Tikrit who was martyred in 575 AD. Mar Hudeni is an old church of the Tikritans in Mosul. It dates back to the 10th century, lies 7 m below street level and was first reconstructed in 1970. People can get mineral water from the well in its yard. The chain, fixed in the wall, is thought to cure epileptics.

- St. George's Monastery (Mar Gurguis): One of the oldest churches in Mosul, named after St. George, located to the north of Mosul, was probably built late in the 17th century. Pilgrims from different parts of the North visit it yearly in the spring, when many people also go out to its whereabouts on holiday. It is about 6 m below street level. A modern church was built over the old one in 1931, abolishing much of its archeological significance. The only monuments left are a marble door-frame decorated with a carved Estrangelo (Syriac) inscription, and two niches, which date back to the 13th or 14th century.

- Mar Matte: This famous monastery is situated about 20 km east of Mosul on the top of a high mountain (Mount Maqloub). It was built by Mar Matte, a monk who fled with several other monks in 362 AD from the Monastery of Zuknin near the City of Amid (Diyarbakir) in the southern part of Asia Minor (modern Turkey) and the north of Iraq during the reign of Emperor Julian the Apostate (361–363 AD). It has a precious library containing Syrianic scriptures.

- Monastery of Mar Behnam: Also called Deir Al-Jubb (The Cistern Monastery) and built in the 12th or 13th century, it lies in the Nineveh Plain near Nimrud about 32 km southwest of Mosul. The monastery, a great fort-like building, rises next to the tomb of Mar Behnam, a prince who was killed by the Sassanians, perhaps during the 4th century AD. A legend made him a son of an Assyrian king.

- St. Elijah's Monastery (Dair Mar Elia): The oldest Christian Monastery in Iraq, it dates from the 6th century.[72]

Other Christian historical buildings:

- The Roman Catholic Church (built by the Dominican Fathers in Nineveh Street in 1893)

- Mar Michael

- Mar Elias

- Mar Oraha

- Rabban Hormizd Monastery, the monastery of Notre-Dame des Semences, near the Assyrian town of Alqosh

Arts

Painting

The so-called Mosul School of Painting refers to a style of miniature painting that developed in northern Iraq in the late 12th to early 13th century under the patronage of the Zangid dynasty (1127–1222). In technique and style the Mosul school was similar to the painting of the Seljuq Turks, who controlled Iraq at that time, but the Mosul artists had a sharper sense of realism based on the subject matter and degree of detail in the painting rather than on representation in three dimensions, which did not occur. Most of the Mosul iconography was Seljuq – for example, the use of figures seated cross-legged in a frontal position. Certain symbolic elements however, such as the crescent and serpents, were derived from the classical Mesopotamian repertory.

Most Mosul paintings were illustrations of manuscripts—mainly scientific works, animal books, and lyric poetry. A frontispiece painting, now held in the Bibliothèque National, Paris, dating from a late 12th century copy of Galen's medical treatise, the Kitab al-diriyak ("Book of Antidotes"), is a good example of the earlier work of the Mosul school. It depicts four figures surrounding a central, seated figure who holds a crescent-shaped halo. The painting is in a variety of whole hues; reds, blues, greens, and gold. The Küfic lettering is blue. The total effect is best described as majestic. Another mid-13th century frontispiece held in the Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, to another copy of the same text suggests the quality of later Mosul painting. There is realism in its depiction of the preparation of a ruler's meal and of horsemen engaged in various activities, and the painting is as many hued as that of the early Mosul school, yet it is somehow less spirited. The composition is more elaborate but less successful. By this time the Baghdad school, which combined the styles of the Syrian and early Mosul schools, had begun to dominate. With the invasion of the Mongols in the mid-13th century the Mosul school came to an end, but its achievements were influential in both the Mamluk and the Mongol schools of miniature painting.

Metalwork

From the 13th-century metal craftsmen centred in Mosul influenced the metalwork of the Islamic world, from North Africa to eastern Iran. Under the active patronage of the Zangid dynasty, the Mosul School developed an extraordinarily refined technique of inlay—particularly in silver—far overshadowing the earlier work of the Sāmānids in Persia and the Būyids in Iraq.

Mosul craftsmen used both gold and silver for inlay on bronze and brass. After delicate engraving had prepared the surface of the piece, strips of gold and silver were worked so carefully that not the slightest irregularity appeared in the whole of the elaborate design. The technique was carried by Mosul metalworkers to Aleppo, Damascus, Baghdad, Cairo, and Persia; similar pieces from those centres are called Mosul bronzes.

Among the most famous surviving Mosul pieces is a brass ewer inlaid with silver from 1232, and now in the British Museum, by the artist Shujā’ ibn Mana. The ewer features representational as well as abstract design, depicting battle scenes, animals and musicians within medallions. Mosul metalworkers also created pieces for Eastern Christians. A candlestick of this variety from 1238 and housed in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, attributed to Dà’ūd ibn Salamah of Mosul, is bronze with silver inlay. It displays the familiar medallions but is also engraved with scenes showing Christ as a child. Rows of standing figures, probably saints, decorate the base. The background is decorated with typically Islamic vine scrolls and intricate arabesques, giving the piece a unique look.

Education

Schools are gender segregated.[57] Previously the city's largest university, the University of Mosul was closed in 2014.[73]

Health

The most important hospitals in Mosul are: Al Jamhuri hospital, Ibn seena hospital, Al Khansaa teaching hospital, Al-Salam teaching hospital, Ibn Alatheer hospital, Mosul General hospital, Al Batool hospital, Oncology and Nuclear medicine hospital, Al Shifaa hospital for infections.

Sport

The city has one football team capable of competing in the top-flight of Iraqi football – Mosul FC.

On the 28 May 2010, Mosul FC beat the Iraqi champions Arbil, in front of a full crowd at the Al Mosul University Stadium by a single goal scored by Anmar Ismaeil.

Notable Moslawis

- Tariq Aziz, Deputy Prime Minister 1979-2003 (from Tel Keppe)

- Munir Bashir, Assyrian musician and famous musician in the Mideast during the 20th century

- Asenath Barzani, first Jewish female rabbi

- Vian Dakhil, current member of the Iraqi parliament

- Hawar Mulla Mohammed, Iraqi soccer player for the national team

- Paulos Faraj Rahho, Assyrian Chaldean Archbishop of Mosul, assassinated 2008

- Taha Yassin Ramadan, former Vice President of Iraq

- Hormuzd Rassam, Assyrian Assyriologist and diplomat

- Kathem Al Saher, Iraqi pop singer, songwriter, and musician

- Salah al-Din al-Sabbagh, Iraqi Army officer

- Ghazi Mashal Ajil al-Yawer, Interim President of Iraq during 2004–2005

- Ignatius Zakka I, Patriarch of Antioch and all east for the Syrian Orthodox Church

- Ignatius Gabriel I Tappouni, Patriarch of Antioch and all east for the Syriac Catholic Church between 1929 - 1968, Church Father of the Second Vatican Council and the first Eastern Rite prelate to be raised to the College of Cardinals since the reign of Pope Pius IX

See also

- Al-Mishraq, site of 2003 sulfur dioxide disaster

- Chaldean Catholic Archeparchy of Mosul

- List of Emirs of Mosul

- List of places in Iraq

- Nineveh plains

- Tel Keppe

- Mosul Question

References

- ↑ Gladstone, Philip (10 February 2014). "Synop Information for ORBM (40608) in Mosul, Iraq". Weather Quality Reporter. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ↑ "Mosul, the next major test for the U.S. military in Iraq". McClatchy CD. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Report on the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict in Iraq: 6 July – 10 September 2014" (PDF). UNAMI and OHCHR. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ Abdulrahim, Raja (5 October 2014). "Iraqi Kurdish forces moving toward complex battle in Mosul". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "Iraq's battles need sense of resolve". BBC News.

- ↑ "Iraq, Islamic State, Baghdad, War", Al monitor, Sep 2014.

- ↑ Laila Ahmed. "Since Islamic State swept into Mosul, we live encircled by its dark fear". the Guardian.

- ↑ Mosul, Iraq from AtlasTours.net

- ↑ "The war against Islamic State (2): Mosul beckons". The Economist. 11 April 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ Genesis 10:11 From that land he went to Assyria, where he built Nineveh, Rehoboth Ir, Calah. Bible.cc. Retrieved on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 עזרא לניאדו, יהודי מוצל, מגלות שומרון עד מבצע עזרא ונחמיה, המכון לחקר יהדות מוצל, טירת-כרמל: ה'תשמ"א.

- ↑ Davidson, Herbert A. (2005). Moses Maimonides: The Man and His Works. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 560. ISBN 0-19-517321-X.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Kemp, Percy (1983). "Power and Knowledge in Jalili Mosul". Middle Eastern Studies 19 (2): 201–12. doi:10.1080/00263208308700543.

- ↑ Al-Tikriti, Nabil (2007). "Ottoman Iraq". Journal of the Historical Society 7 (2): 201–11. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2007.00214.x.

- ↑ Khoury, Dina Rizk (1997), State and Provincial Society in the Ottoman Empire. Mosul, 1540–1834, Studies in Islamic Civilization, Cambridge, p. 19.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Woods, Richard (2006). "Iraq Perspectives: Catholics and Dominicans in Iraq". Dominican Life. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ↑ Rasam, Suha (2005). Christianity in Iraq: its origins and development to the present day. Gracewing. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Shields, Sarah D. (2000). Mosul before Iraq; Like Bees Making Five-Sided Cells. Albanay: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4487-2.

- ↑ Pentagon: Saddam's sons killed in raid . CNN.com (2003-07-22). Retrieved on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ Mosul. Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ Iraq reopens Mosul airport after 14 years – US military

- ↑ Gamel, Kim (January 25, 2008). "Provincial Police Chief Killed in Mosul". Associated Press.

- ↑ "Sadrists and Iraqi Government Reach Truce Deal". New York Times. May 11, 2008.

- ↑ Archived October 11, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Plight of Iraqi Academics at the Wayback Machine (archived May 15, 2006)

- ↑ Human Rights in Iraq at the Wayback Machine (archived June 29, 2006)

- ↑ "Iraq's deadly brain drain". France 24. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Losing Mosul?". Time. October 16, 2004. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ↑ Muir, Jim. (2008-10-28) Middle East | Iraqi Christians' fear of exile. BBC News. Retrieved on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "Christians flee Iraqi city after killings, threats, officials say." CNN. 11 October 2008.

- ↑ "Iraqi insurgents seize city". BBC. 11 June 2014.

- ↑ "Militant group seizes cities in Iraq". CNN. 11 June 2014.

- ↑ "How Mosul fell - An Iraqi general disputes Baghdad's story". Reuters. 14 October 2014.

- ↑ Richard Spencer (22 June 2014). "How US and Britain were warned of Isis advance in Iraq but 'turned a deaf ear'". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Since Islamic State swept into Mosul, we live encircled by its dark fear". Guardian. 29 August 2014.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Adam Holloway (26 September 2014). "Sharing a border with Isil - the world's most dangerous state". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "Under an ISIS Flag, the Sons of Mosul Are Rallying". Daily Beast. 16 June 2014.

- ↑ Morris, Loveday.'Kurds say they have ejected Islamic State militants from large area in Northern Iraq'.January 22, 2015 Washington Post.http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/kurds-say-they-have-ejected-islamic-state-from-a-big-area-in-northern-iraq/2015/01/21/ac459372-a1c6-11e4-b146-577832eafcb4_story.html, retrieved January 25, 2015

- ↑ "BBC News - Islamic State crisis: Mother fears for son at Mosul school". BBC News.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Rubin, Alissa J. (18 July 2014) ISIS Forces Last Iraqi Christians to Flee Mosul'. Retrieved 1 August 2013

- ↑ Al Arabiya News (26 July 2014) destroys Prophet Sheth shrine in Mosul'. Retrieved 1 August 2014

- ↑ "Isis militants blow up Jonah's tomb". The Guardian. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ Buchanan, Rose Troup and Saul, Heather (25 February 2015) Isis burns thousands of books and rare manuscripts from Mosul's libraries The Independent

- ↑ ISIL video shows destruction of Mosul artefacts 27 Feb 2015 Al Jazeera

- ↑ Shaheen, Kareem (26 February 2015) Isis fighters destroy ancient artefacts at Mosul museum The Guardian

- ↑ Kariml, Ammar; Mojon, Jean-Marc. (31 July 2014) In Mosul, resistance against ISIS rises from city’s rubble'. The Daily Star-Lebanon, Retrieved 1 August 2014

- ↑ Sevil Erkuş (25 September 2014). "Mosul Consulate ‘overpowered’ by ISIL militants at the gates, Turkish hostage says - MIDEAST". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "UN Envoy Condemns Public Execution of Human Rights Lawyer, Ms. Sameera Al-Nuaimy". United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI).

- ↑ "Report on the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict in Iraq: 6 July – 10 September 2014" (PDF). Executions following illegal/irregular/unlawful courts, in disrespect of due process and fair trial standards: UNAMI Human Rights Office.

- ↑ Mezzofiore, Gianluca (30 July 2014) 'Mosul Brigades: Local Armed Resistance to Islamic State Gains Support'. Retrieved 1 August 2014

- ↑ "IS Cracks Down In Mosul, Fearing Residents Mobilizing Against Them". http://www.rferl.org

- ↑ Mosul| Encyclopedia.com: Facts, Pictures, Information. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ ArabNet Mosul Entry ArabNet

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica Originally appearing in Volume V18, Page 904

- ↑ Mosul. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ Cf. Carlos C. Huerta, Jewish heartbreak and hope in Nineveh.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 "Islamic State: Diary of life in Mosul". BBC.

- ↑ "Iraqi army readies for assault on Mosul". Al Jazeera. 10 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ "Citizens of Mosul endure economic collapse and repression under Isis rule". Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ "In Mosul, Water, Electricity Shortages, And Warnings Of Disease".

- ↑ Snow in Mosul Photo - Mosul

- ↑ Early snow fall in Mosul. | Flickr - Photo Sharing!

- ↑ Het weer. Weersverwachtingen. Huidig weer. Weeralarmen bij zwaar weer | freemeteo.nl

- ↑ "World Weather Information Service – Mosul". United Nations. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ↑ "Mosul, Iraq Travel Weather Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- ↑ ISIS destroys ‘Jonah’s tomb’ in Mosul

- ↑ Islamic State destroys ancient Mosul mosque, the third in a week

- ↑ Clark, Heather (27 July 2014). "Muslim Militants Blow Up Tombs of Biblical Jonah, Daniel in Iraq". Christian News Network. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

Al-Sumaria News also reported on Thursday that local Mosul official Zuhair al-Chalabi told the outlet that ISIS likewise “implanted explosives around Prophet Daniel’s tomb in Mosul and blasted it, leading to its destruction.”

- ↑ Hafiz, Yasmine. "ISIS Destroys Jonah's Tomb In Mosul, Iraq, As Militant Violence Continues". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

The tomb of Daniel, a man revered by Muslims as a prophet though unlike Jonah, he is not mentioned in the Quran, has also been reportedly destroyed. Al-Arabiya reports that Zuhair al-Chalabi, a local Mosul official, told Al-Samaria News that “ISIS implanted explosives around Prophet Daniel’s tomb in Mosul and blasted it, leading to its destruction."

- ↑ ISIS destroys beloved mosque in central Mosul

- ↑ Iraq: Isis destroys 19th century Ottoman mosque in central Mosul

- ↑ Chaplains Struggle to Protect Monastery in Iraq. NPR's Morning Edition, 21 November 2007. Retrieved on 2011-07-02.

- ↑ "ISIS Takeover In Iraq: Mosul University Students, Faculty Uncertain About The Future Of Higher Education". IBT. 3 December 2014.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- Jedidiah Morse; Richard C. Morse (1823), "Mosul", A New Universal Gazetteer (4th ed.), New Haven: S. Converse

- "Mosul". Edinburgh Gazetteer (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. 1829.

- Josiah Conder (1834), "Mosul", Dictionary of Geography, Ancient and Modern, London: T. Tegg

- Charles Wilson, ed. (1895), "Mosul", Handbook for Travellers in Asia Minor, Transcaucasia, Persia, etc., London: John Murray, OCLC 8979039

- Edward Balfour, ed. (1871). "Mosul". Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia (2nd ed.). Madras.

- Published in the 20th century

- "Mosul", Palestine and Syria (5th ed.), Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1912

- "Mosul". Encyclopaedia of Islam. E.J. Brill. 1934. p. 609+.

- Jacqueline Griffin (1996), "Mosul", in Trudy Ring, Middle East and Africa, International Dictionary of Historic Places, Routledge, ISBN 9781884964039

- Published in the 21st century

- C. Edmund Bosworth, ed. (2007). "Mosul". Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 9004153888.

- Michael R.T. Dumper; Bruce E. Stanley, eds. (2008), "Mosul", Cities of the Middle East and North Africa, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1576079198

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mosul. |

- ninava-explorer

- Iraq Image – Mosul Satellite Observation

- Detailed map of Mosul by the National Imagery and Mapping Agency, from lib.utexas.edu

- ArchNet.org. "Mosul". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning.

| ||||||||||||||||