Morisco rebellions in Granada

In southern Spain, following the conquest of Granada city in 1492 by the "Catholic Monarchs" - Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel of Castile - the Moorish inhabitants of the city and province twice revolted against Christian rule. The second rebellion led to the expulsion of 80,000 Moriscos from the city and province. The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices occurred in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences. From then on, indigenous Islam is considered to have been extinguished in Spain.[1]

The fall of Granada and the first rebellion of the Moors, 1499-1500

In the wake of the Reconquista most of the Moors had continued to live in Spain, and until the 16th century were granted religious freedom, albeit subject to some legal discrimination. They became known as Mudéjares.

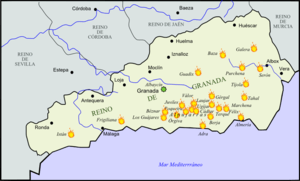

The Kingdom of Granada was the last Muslim-ruled state in Spain. After a long siege, the city of Granada fell to the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella I, in 1492. The Muslim population was initially tolerated under the terms of the Treaty of Granada. However, pressure on them to convert to Christianity led to the 1499 uprising in Granada city, quickly put down, and in the following year to more serious revolts in the mountain villages of the Alpujarra - the region below the Sierra Nevada; Ferdinand himself led an army into the area. There were also revolts in the western parts of the former Kingdom. Suppression by the Catholic forces was severe; in one village (Andarax) they blew up the principal mosque, in which women and children had taken refuge.

The revolt enabled the Catholics to claim that the Muslims had violated the terms of the Treaty of Granada, which were therefore withdrawn. Throughout the region, Moors were thus forced to choose between conversion to Christianity or exile. They became known as "Moriscos" or "New Christians", though many continued to speak Arabic and to wear Moorish clothing.

Interlude

In 1526, Charles I (of Spain - he later became Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor) - issued an Edict under which laws against heresy (e.g. Muslim practices by "New Christians") would be strictly enforced; among other restrictions, it forbade the use of Arabic and the wearing of Moorish dress. The Moriscos managed to get this suspended for forty years by the payment of a large sum (80,000 ducados).

Since now all remaining Moors were officially Christian, mosques could be destroyed or turned into churches. Their children had to be baptised; marriage had to be performed by a priest.

In 1556 Philip II became King, and in 1566 the forty-year suspension of the Edict ran out. It was revised by a "Pragmatica" - even more severe as it required the Moriscos to learn Castilian within three years, after which no-one would be allowed to use Arabic. Moorish names were not to be used; Moorish garments were forbidden. And in 1567 Philip II issued a decree ending all toleration of Moorish culture. He banned the Arabic and Berber languages, prohibited Moorish dress, required Moriscos to adopt Christian names, ordered the destruction of all books and documents in Arabic script, and decreed that Morisco children would be educated only by Catholic priests.

The second rebellion, 1568-71

Philip's harsh approach sparked the outbreak of armed rebellion throughout the former Kingdom of Granada; it is also known as the War of Las Alpujarras. It began in Granada city on Christmas Eve of 1568, but this failed because only a small number of rebels turned up (heavy snowfall in the mountains had prevented others from arriving).

However, Moriscos of Granada, the Alpujarras, and elsewhere, including many who had fled from their villages under Christian rule and become outlaws in the mountains (monfies), secretly assembled in the Valle de Lecrin. They repudiated Christianity, and proclaimed Aben Humeya (born Fernando de Valor, and he claimed descent from the former Umayad dynasty) as their king.

The mountain villages had joined the revolt, burning churches, assassinating priests and other Christians. The Marques of Mondejar led an army into the Alpujarra. In the first major battle, despite difficult terrain, he managed to take control of the Poqueira valley, where Aben Humeya had set up his headquarters. From there, his forces continued through the mountain, taking many villages, rescuing Christians whom the Moriscos had imprisoned in churches.

The war however degenerated into massacres and pillage, with atrocities committed by both sides. In the next year, when the number of rebels had greatly increased, Philip II replaced the Marques of Mondejar - considered too lenient - with his own half-brother John of Austria, with a large force of Spanish and Italian troops. The rebels, divided and disorganised, lost to a ruthless enemy whatever gains they had made. Aben Humeya was assassinated by his own followers and replaced by Aben Aboo. The war came to an end in March 1571, when Aben Aboo in his turn was killed by his own people.

Aftermath

After the suppression of the revolt, almost the entire Morisco population was expelled from the former Kingdom of Granada. First rounded up and held in churches, then in harsh winter conditions, with little food, they were taken on foot in groups, escorted by soldiers; many died on the way. Many went to Cordova, others to Toledo and as far as Leon. Those from the Almería region were taken in galleys as far as Seville. The total number expelled has been estimated at some 80,000.

In the rural areas, the exiled Moriscos were partially replaced with Christian settlers brought in from other parts of Spain, even as far away as Galicia. These settlers, lacking experience of mountain farming, had a difficult time, and some gave up. Some villages were abandoned. While the Morisco population of the Alpujarra can be estimated at some 40,000 before the revolt, the population by the end of the century was probably only about 7,000.

In ordering the dispersal of the Moriscos to other parts of the country, Philip had expected that this would fragment the Morisco community and accelerate their assimilation into the Christian population. However, the Moriscos from Granada actually had some influence on the local Moriscos who had until then become more assimilated. Nevertheless, in 1609 King Philip III ordered the expulsion of Moriscos from everywhere in Spain; most ended in North Africa as their final destination, others avoided expulsion or managed to return.

References

Sources

- Mármol de Carvajal, Historia de la Rebelión y Castigo de los Moriscos del Reino de Granada (1600).

- Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, Guerra de Granada (1627).

- Julio Caro Barata, Los Moriscos del Reino de Granada (1999).

- Justo Navarro, El país perdido: la Alpujarra en la guerra morisca, Fundación José Manuel Lara, 2013, ISBN 9788496824232.

- Michael Tracy, Bubión - the story of an Alpujarran village (2013).

- Kaplan, Benjamin J., Religious Conflict and the Practice of Toleration in Early Modern Europe, Harvard University Press, 2007, pp. 310–311.

- Zagorin, Perez, Rebels and rulers, 1500-1660, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982, pp. 13–15.