Moonshine

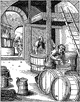

Moonshine, white lightning, mountain dew, hooch, and white whiskey are terms used to describe high-proof distilled spirits that are generally produced illicitly.[1][2] Moonshine is typically made with corn mash as the main ingredient.[3] The word "moonshine" is believed to be derived from the term "moonrakers" used for early English smugglers and the clandestine (i.e., by the light of the moon) nature of the operations of illegal Appalachian distillers who produced and distributed whiskey.[4][5] The distillation was done at night to avoid discovery.[6]

Moonshine was especially important to the Appalachian area. This white whiskey most likely entered the Appalachian region in the late 1700s to early 1800s. Scots-Irish immigrants from the Ulster region of Northern Ireland brought their recipe for their uisce beatha, Gaelic for "water of life". The settlers made their whiskey without aging it, and this is the same recipe that became traditional in the Appalachian area.[7]

Years after these initial settlers, moonshine served as a source of income for many Appalachian residents. In early 20th century Cocke County, Tennessee, farmers made moonshine from their own corn crop in order to transport more value in a smaller load.[8] Moonshine allowed them to bring in additional income while at the same time cutting down on transportation costs. Moonshiners in Harlan County, Kentucky, like Maggie Bailey, made the whiskey to sell in order to provide for their families.[9]

In modern usage, the term "moonshine" ordinarily implies that the liquor is produced illegally; however, the term has also been used on the labels of some legal products as a way of marketing them as providing a similar drinking experience as found with illegal liquor.

Safety

Poorly produced moonshine can be contaminated, mainly from materials used in the construction of the still. Stills employing automotive radiators as condensers are particularly dangerous; in some cases, glycol, products from antifreeze, can appear as well. Radiators used as condensers also may contain lead at the connections to the plumbing. These methods often resulted in blindness or lead poisoning for those consuming tainted liquor.[10] This was an issue during Prohibition when many died from ingesting unhealthy substances.

Although methanol is not produced in toxic amounts by fermentation of sugars from grain starches,[11] contamination is still possible by unscrupulous distillers using cheap methanol to increase the apparent strength of the product. Moonshine can be made both more palatable and less damaging by discarding the "foreshot"—the first few ounces of alcohol that drip from the condenser. The foreshot contains most of the methanol, if any, from the mash because methanol vaporizes at a lower temperature than ethanol. The foreshot also typically contains small amounts of other undesirable compounds such as acetone and various aldehydes.

Alcohol concentrations above about 50% alcohol by volume (101 proof) are flammable and therefore dangerous to handle. This is especially true during the distilling process when vaporized alcohol may accumulate in the air to dangerous concentrations if adequate ventilation has not been provided.[12]

Tests

A quick estimate of the alcoholic strength, or proof, of the distillate (the ratio of alcohol to water) is often achieved by shaking a clear container of the distillate. Large bubbles with a short duration indicate a higher alcohol content, while smaller bubbles that disappear more slowly indicate lower alcohol content.

A common folk test for the quality of moonshine was to pour a small quantity of it into a spoon and set it on fire. The theory was that a safe distillate burns with a blue flame, but a tainted distillate burns with a yellow flame. Practitioners of this simple test also held that if a radiator coil had been used as a condenser, then there would be lead in the distillate, which would give a reddish flame. This led to the mnemonic, "Lead burns red and makes you dead." or "Red means dead."[13] Although the flame test will show the presence of lead and fusel oils, it will not reveal the presence of methanol (also poisonous), which burns with an invisible flame.[14]

Prevalence

Varieties of moonshine are produced throughout the world.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Guy Logsdon. "Moonshine". Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ http://www.flasks.com/blog/what-is-moonshine/

- ↑ Guy Logsdon. "Moonshine". Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ↑ Ellison, Betty Boles (2003). Illegal Odyssey: 200 Years of Kentucky Moonshine. IN: Author House. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4107-8407-0.

- ↑ Kellner, Esther (1971). Moonshine: its history and folklore. IN: Bobbs-Merrill. p. 5.

- ↑ Jason Sumich. "It's All Legal Until You Get Caught: Moonshining in the Southern Appalachians". Appalachian State University. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ Joyce, Jamie (2014). Moonshine: A Cultural History of America's Infamous Liquor. Minneapolis: Zenith. pp. 8–14. ISBN 978-0-7603-4584-9.

- ↑ Peine, Emelie K.; Schafft, Kai A. (2012). "Moonshine, Mountaineers, and Modernity: Distilling Cultural History in the Southern Appalachian Mountains". Journal of Appalachian Studies 18: 99.

- ↑ Block, Melissa. ""'Queen of the Mountain Bootleggers' Maggie Bailey"". National Public Radio. Retrieved 12/4/14. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Peine, Emelie K.; Schafft, Kai A. (2012). "Moonshine, Mountaineers, and Modernity: Distilling Cultural History in the Southern Appalachian Mountains". Journal of Appalachian Studies 18: 97.

- ↑ "Distillation: Some Purity Considerations", A Step By Step Guide

- ↑ "How to Make Moonshine Safely". Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ "Moonshine". Skylark Medical Clinic. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ↑ Methanol Institute

Further reading

- Davis, Elaine. Minnesota 13: "Wet" Wild Prohibition Days (2007) ISBN 9780979801709

- Peine, Emelie K., and Kai A. Schafft. “Moonshine, Mountaineers, and Modernity: Distilling Cultural History in the Southern Appalachian Mountains,” Journal of Appalachian Studies, 18 (Spring–Fall 2012), 93–112.

- Rowley, Matthew. Moonshine! History, songs, stories, and how-tos (2007) ISBN 9781579906481

- Watman, Max. Chasing the White Dog: An Amateur Outlaw's Adventures in Moonshine (2010) ISBN 9781439170243

- King, Jeff. The Home Distiller's Workbook: Your Guide to Making Moonshine, Whisky, Vodka, Rum and So Much More! (2012) ISBN 9781469989396

External links

- "Moonshine – Blue Ridge Style" An Exhibition Produced by the Blue Ridge Institute and the Museum of Ferrum College

- Déantús an Phoitín (Poteen Making), by MacDara Ó Curraidhín, is a one-hour documentary film on the origins of the craft.

- North Carolina Moonshine – Historical information, images, music, and film excerpts

- Moonshine news page – Alcohol and Drugs History Society

- Georgia Moonshine – History and folk traditions in Georgia, USA

- "Moonshine 'tempts new generation'" – BBC on distilling illegal liquor in the 21st century.

- Moonshine Franklin Co Virginia Moonshine Still from the past – Video

- Home Moonshine Distiller Making Moonshine at home – Video

| ||||||||||||||||||