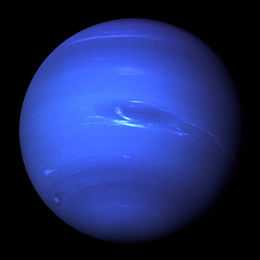

Moons of Neptune

Neptune has 14 known moons, which are named for minor water deities in Greek mythology.[note 1] By far the largest of them is Triton, discovered by William Lassell on October 10, 1846, just 17 days after the discovery of Neptune itself; over a century passed before the discovery of the second natural satellite, Nereid. The moon orbiting farthest from its planet in the Solar System is Neptune's Neso and has an orbital period of about 26 yrs.[1]

Triton is unique among moons of planetary mass in that its orbit is retrograde to Neptune's rotation and inclined relative to Neptune's equator, which suggests that it did not form in orbit around Neptune but was instead gravitationally captured by it. The next-largest irregular satellite in the Solar System, Saturn's moon Phoebe, has only 0.03% of Triton's mass. The capture of Triton, probably occurring some time after Neptune formed a satellite system, was a catastrophic event for Neptune's original satellites, disrupting their orbits so that they collided to form a rubble disc. Triton is massive enough to have achieved hydrostatic equilibrium and to retain a thin atmosphere capable of forming clouds and hazes.

Inward of Triton are seven small regular satellites, all of which have prograde orbits in planes that lie close to Neptune's equatorial plane; some of these orbit among Neptune's rings. The largest of them is Proteus. They were re-accreted from the rubble disc generated after Triton's capture after the Tritonian orbit became circular. Neptune also has six more outer irregular satellites other than Triton, including Nereid, whose orbits are much farther from Neptune and at high inclination: three of these have prograde orbits, while the remainder have retrograde orbits. In particular, Nereid has an unusually close and eccentric orbit for an irregular satellite, suggesting that it may have once been a regular satellite that was significantly perturbed to its current position when Triton was captured. The two outermost Neptunian irregular satellites, Psamathe and Neso, have the largest orbits of any natural satellites discovered in the Solar System to date.

Discovery and naming

Discovery

Triton was discovered by William Lassell in 1846, just seventeen days after the discovery of Neptune.[2] Nereid was discovered by Gerard P. Kuiper in 1949.[3] The third moon, later named Larissa, was first observed by Harold J. Reitsema, William B. Hubbard, Larry A. Lebofsky and David J. Tholen on May 24, 1981. The astronomers were observing a star's close approach to Neptune, looking for rings similar to those discovered around Uranus four years earlier.[4] If rings were present, the star's luminosity would decrease slightly just before the planet's closest approach. The star's luminosity dipped only for several seconds, which meant that it was due to a moon rather than a ring.

No further moons were found until Voyager 2 flew by Neptune in 1989. Voyager 2 rediscovered Larissa and discovered five inner moons: Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, Galatea and Proteus.[5] In 2001 two surveys using large ground-based telescopes found five additional outer moons, bringing the total to thirteen.[6] Follow-up surveys by two teams in 2002 and 2003 respectively re-observed all five of these moons, which are Halimede, Sao, Psamathe, Laomedeia, and Neso.[6][7] A sixth candidate moon was also found in the 2002 survey and was lost thereafter: it may have been a centaur instead of a satellite, although its small amount of motion relative to Neptune over a month suggests that it was indeed a satellite.[6] It was estimated to have diameter 33 km and to have been about 25.1 million km (0.168 AU) from Neptune when it was found.[6]

On July 15, 2013, a team of astronomers led by Mark R. Showalter of the SETI Institute revealed to Sky & Telescope magazine that they had discovered a previously unknown fourteenth moon in images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope from 2004–2009. The as yet unnamed fourteenth moon, currently identified as S/2004 N 1, is thought to measure no more than 16–20 km in diameter.[8]

Names

Triton did not have an official name until the twentieth century. The name "Triton" was suggested by Camille Flammarion in his 1880 book Astronomie Populaire,[9] but it did not come into common use until at least the 1930s.[10] Until this time it was usually simply known as "the satellite of Neptune". Other moons of Neptune are also named for Greek and Roman water gods, in keeping with Neptune's position as god of the sea:[11] either from Greek mythology, usually children of Poseidon, the Greek Neptune (Triton, Proteus, Despina, Thalassa); classes of minor Greek water deity (Naiad, Nereid); or specific Nereids (Halimede, Galatea, Neso, Sao, Laomedeia, Psamathe).[11] Two asteroids share the same names as moons of Neptune: 74 Galatea and 1162 Larissa.

Characteristics

The moons of Neptune can be divided into two groups: regular and irregular. The first group includes the seven inner moons, which follow circular prograde orbits lying in the equatorial plane of Neptune. The second group consists of all other moons including Triton. They generally follow inclined eccentric and often retrograde orbits far from Neptune; the only exception is Triton, which orbits close to the planet following a circular orbit, though retrograde and inclined.[12]

Regular moons

In order of distance from Neptune, the regular moons are Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, Galatea, Larissa, S/2004 N 1, and Proteus. Naiad, the closest regular moon, is also the second smallest among the inner moons (following the discovery of S/2004 N 1), whereas Proteus is the largest regular moon and the second largest moon of Neptune. The inner moons are closely associated with Neptune's rings. The two innermost satellites, Naiad and Thalassa, orbit between the Galle and LeVerrier rings.[5] Despina may be a shepherd moon of the LeVerrier ring, because its orbit lies just inside this ring.[13]

The next moon, Galatea, orbits just inside the most prominent of Neptune's rings, the Adams ring.[13] This ring is very narrow, with a width not exceeding 50 km,[14] and has five embedded bright arcs.[13] The gravity of Galatea helps confine the ring particles within a limited region in the radial direction, maintaining the narrow ring. Various resonances between the ring particles and Galatea may also have a role in maintaining the arcs.[13]

Only the two largest regular moons have been imaged with a resolution sufficient to discern their shapes and surface features.[5] Larissa, about 200 km in diameter, is elongated. Proteus is not significantly elongated, but not fully spherical either:[5] it resembles an irregular polyhedron, with several flat or slightly concave facets 150 to 250 km in diameter.[15] At about 400 km in diameter, it is larger than the Saturnian moon Mimas, which is fully ellipsoidal. This difference may be due to a past collisional disruption of Proteus.[16] The surface of Proteus is heavily cratered and shows a number of linear features. Its largest crater, Pharos, is more than 150 km in diameter.[5][15]

All of Neptune's inner moons are dark objects: their geometrical albedo ranges from 7 to 10%.[17] Their spectra indicate that they are made from water ice contaminated by some very dark material, probably complex organic compounds. In this respect, the inner Neptunian moons are similar to the inner moons of Uranus.[5]

Irregular moons

In order of their distance from the planet, the irregular moons are Triton, Nereid, Halimede, Sao, Laomedeia, Neso and Psamathe, a group that includes both prograde and retrograde objects.[12] The five outer moons are similar to the irregular moons of other giant planets, and are believed to have been gravitationally captured by Neptune, unlike the regular satellites which probably formed in situ.[7]

Triton and Nereid are unusual irregular satellites and are thus treated separately from the other five irregular Neptunian moons, which are more like the outer irregular satellites of the other outer planets.[7] Firstly, they are the largest two known irregular moons in the Solar System, with Triton being almost an order of magnitude larger than all other known irregular moons. Secondly, they both have atypically small semi-major axes, with Triton's being over an order of magnitude smaller than those of all other known irregular moons. Thirdly, they both have unusual orbital eccentricities: Nereid has one of the most eccentric orbits of any known irregular satellite, and Triton's orbit is a nearly perfect circle. Finally, Nereid also has the lowest inclination of any known irregular satellite.[7]

Triton

Triton follows a retrograde and quasi-circular orbit, and is thought to be a gravitationally captured satellite. It was the second moon in the Solar System that was discovered to have a substantial atmosphere, which is primarily nitrogen with small amounts of methane and carbon monoxide.[18] The pressure on Triton's surface is about 14 μbar.[18] In 1989 the Voyager 2 spacecraft observed what appeared to be clouds and hazes in this thin atmosphere.[5] Triton is one of the coldest bodies in the Solar System, with a surface temperature of about 38 K (−235.2 °C).[18] Its surface is covered by nitrogen, methane, carbon dioxide and water ices[19] and has a high geometric albedo of more than 70%.[5] The Bond albedo is even higher, reaching up to 90%.[5][note 2] Surface features include the large southern polar cap, older cratered planes cross-cut by graben and scarps, as well as youthful features probably formed by endogenic processes like cryovolcanism.[5] Voyager 2 observations revealed a number of active geysers within the polar cap heated by the Sun, which eject plumes to the height of up to 8 km.[5] Triton has a relatively high density of about 2 g/cm3 indicating that rocks constitute about two thirds of its mass, and ices (mainly water ice) the remaining one third. There may be a layer of liquid water deep inside Triton, forming a subterranean ocean.[20]

Nereid

Nereid is the third-largest moon of Neptune. It has a prograde but very eccentric orbit and is believed to be a former regular satellite that was scattered to its current orbit through gravitational interactions during Triton's capture.[21] Water ice has been spectroscopically detected on its surface. Nereid shows large, irregular variations in its visible magnitude, which are probably caused by forced precession or chaotic rotation combined with an elongated shape and bright or dark spots on the surface.[22]

Normal irregular moons

Among the remaining irregular moons, Sao and Laomedeia follow prograde orbits, whereas Halimede, Psamathe and Neso follow retrograde orbits. Given the similarity of their orbits, it was suggested that Neso and Psamathe could have a common origin in the break-up of a larger moon.[7] Psamathe and Neso have the largest orbits of any natural satellites discovered in the Solar system to date. They take 25 years to orbit Neptune at an average of 125 times the distance between Earth and the Moon. Neptune has the largest Hill sphere in the Solar System, owing primarily to its large distance from the Sun; this allows it to retain control of such distant moons.[12] Nevertheless, Jupiter's S/2003 J 2 orbits at the greatest percentage of the primary's Hill radius of all the moons in the Solar System on average, and the Jovian moons in the Carme and Pasiphae groups orbit at a greater percentage of their primary's Hill radius than Psamathe and Neso.[12]

Formation

The mass distribution of the Neptunian moons is the most lopsided of any group of gas giant satellites in the Solar System. One moon, Triton, makes up nearly all of the mass of the system, with all other moons together comprising only one third of one percent. This may be because Triton was captured well after the formation of Neptune's original satellite system, much of which would have been destroyed in the process of capture.[21][23][note 3]

Triton's orbit upon capture would have been highly eccentric, and would have caused chaotic perturbations in the orbits of the original inner Neptunian satellites, causing them to collide and reduce to a disc of rubble.[21] This means it is likely that Neptune's present inner satellites are not the original bodies that formed with Neptune. Only after Triton's orbit became circularised could some of the rubble re-accrete into the present-day regular moons.[16] This great perturbation may possibly be the reason why the satellite system of Neptune does not follow the 10,000:1 ratio of mass between the parent planet and all its moons seen in the satellite systems of all the other gas giants.[24]

The mechanism of Triton’s capture has been the subject of several theories over the years. One of them postulates that Triton was captured in a three-body encounter. In this scenario, Triton is the surviving member of a binary Kuiper belt object[note 4] disrupted by its encounter with Neptune.[25]

Numerical simulations show that there is a 0.41 probability that the moon Halimede collided with Nereid at some time in the past.[6] Although it is not known whether any collision has taken place, both moons appear to have similar ("grey") colors, implying that Halimede could be a fragment of Nereid.[26]

Table

| ‡ Prograde irregular moons |

♠ Retrograde irregular moons |

The Neptunian moons are listed here by orbital period, from shortest to longest. Irregular (captured) moons are marked by color. Triton, the only Neptunian moon massive enough for its surface to have collapsed into a spheroid, is bolded.

| Order [note 5] |

Label [note 6] |

Name | Pronunciation (key) |

Image | Diameter (km)[note 7] |

Mass (×1016 kg) [note 8] |

Semi-major axis (km)[29] |

Orbital period (d)[29] |

Orbital inclination (°)[29][note 9] |

Eccentricity [29] |

Discovery year[11] |

Discoverer [11] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neptune III | Naiad | /ˈneɪ.əd/ | | 66 (96 × 60 × 52) | ≈ 19 | 48227 | 0.294 | 4.691 | 0.0003 | 1989 | Voyager Science Team |

| 2 | Neptune IV | Thalassa | /θəˈlæsə/ | | 82 (108 × 100 × 52) | ≈ 35 | 50074 | 0.311 | 0.135 | 0.0002 | 1989 | Voyager Science Team |

| 3 | Neptune V | Despina | /dɨsˈpiːnə/ | | 150 (180 × 148 × 128) | ≈ 210 | 52526 | 0.335 | 0.068 | 0.0002 | 1989 | Voyager Science Team |

| 4 | Neptune VI | Galatea | /ˌɡæləˈtiːə/ |  | 176 (204 × 184 × 144) | ≈ 375 | 61953 | 0.429 | 0.034 | 0.0001 | 1989 | Voyager Science Team |

| 5 | Neptune VII | Larissa | /ləˈrɪsə/ | | 194 (216 × 204 × 168) | ≈ 495 | 73548 | 0.555 | 0.205 | 0.0014 | 1981 | Reitsema et al. |

| 6 | — | S/2004 N 1 | | ≈ 16–20[8] | ≈ 0.5 ± 0.4 | 105300 ± 50 | 0.936[8] | 0.000 | 0.0000 | 2013 | Showalter et al.[30] | |

| 7 | Neptune VIII | Proteus | /ˈproʊtiəs/ | .jpg) | 420 (436 × 416 × 402) | ≈ 5035 | 117646 | 1.122 | 0.075 | 0.0005 | 1989 | Voyager Science Team |

| 8 | Neptune I | Triton♠ | /ˈtraɪtən/ | .jpg) | 2705.2±4.8 (2709 × 2706 × 2705) | 2140800±5200 | 354759 | −5.877 | 156.865 | 0.0000 | 1846 | Lassell |

| 9 | Neptune II | Nereid‡ | /ˈnɪəriː.ɪd/ |  | ≈ 340 ± 50 | ≈ 2700 | 5513818 | 360.13 | 7.090 | 0.7507 | 1949 | Kuiper |

| 10 | Neptune IX | Halimede♠ | /ˌhælɨˈmiːdiː/ | | ≈ 62 | ≈ 16 | 16611000 | −1879.08 | 112.898 | 0.2646 | 2002 | Holman et al. |

| 11 | Neptune XI | Sao‡ | /ˈseɪ.oʊ/ | ≈ 44 | ≈ 6 | 22228000 | 2912.72 | 49.907 | 0.1365 | 2002 | Holman et al. | |

| 12 | Neptune XII | Laomedeia‡ | /ˌleɪ.ɵmɨˈdiːə/ | ≈ 42 | ≈ 5 | 23567000 | 3171.33 | 34.049 | 0.3969 | 2002 | Holman et al. | |

| 13 | Neptune X | Psamathe♠ | /ˈsæməθiː/ |  | ≈ 40 | ≈ 4 | 48096000 | −9074.30 | 137.679 | 0.3809 | 2003 | Sheppard et al. |

| 14 | Neptune XIII | Neso♠ | /ˈniːsoʊ/ | ≈ 60 | ≈ 15 | 49285000 | −9740.73 | 131.265 | 0.5714 | 2002 | Holman et al. |

Notes

- ↑ This is a IAU guideline that will be followed at the naming of every Neptunian moon, although one (S/2004 N 1) has yet to receive a permanent name.

- ↑ The geometric albedo of an astronomical body is the ratio of its actual brightness at zero phase angle (i.e. as seen from the light source) to that of an idealized flat, fully reflecting, diffusively scattering (Lambertian) disk with the same cross-section. The Bond albedo, named after the American astronomer George Phillips Bond (1825–1865), who originally proposed it, is the fraction of power in the total electromagnetic radiation incident on an astronomical body that is scattered back out into space. The Bond albedo is a value strictly between 0 and 1, as it includes all possible scattered light (but not radiation from the body itself). This is in contrast to other definitions of albedo such as the geometric albedo, which can be above 1. In general, though, the Bond albedo may be greater or smaller than the geometric albedo, depending on surface and atmospheric properties of the body in question.

- ↑ Saturn's satellite system is the next most lopsided, with most of its mass being in its largest moon Titan. Jupiter and Uranus have more balanced systems.

- ↑ Binary objects, objects with moons such as the Pluto–Charon system, are quite common among the larger trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). Around 11% of all TNOs may be binaries.[25]

- ↑ Order refers to the position among other moons with respect to their average distance from Neptune.

- ↑ Label refers to the Roman numeral attributed to each moon in order of their discovery.[11]

- ↑ Diameters with multiple entries such as "60×40×34" reflect that the body is not spherical and that each of its dimensions has been measured well enough to provide a 3 axis estimate. The dimensions of the five inner moons were taken from Karkoschka, 2003.[17] Dimensions of Proteus are from Stooke (1994).[15] Dimensions of Triton are from Thomas, 2000,[27] whereas its diameter is taken from Davies et al., 1991.[28] The size of Nereid is from Smith, 1989.[5] The sizes of the outer moons are from Sheppard et al., 2006.[7]

- ↑ Mass of all moons of Neptune except Triton were calculated assuming a density of 1.3 g/cm³. The volumes of Larissa and Proteus were taken from Stooke (1994).[15] The mass of Triton is from Jacobson, 2009.

- ↑ Each moon's inclination is given relative to its local Laplace plane. Inclinations greater than 90° indicate retrograde orbits (in the direction opposite to the planet's rotation).

References

- ↑ http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_elem#neptune (as of Dec-2014)

- ↑ Lassell, W. (1846). "Discovery of supposed ring and satellite of Neptune". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 7: 157. Bibcode:1846MNRAS...7..157L.

- ↑ Kuiper, Gerard P. (1949). "The Second Satellite of Neptune". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 61 (361): 175–176. Bibcode:1949PASP...61..175K. doi:10.1086/126166.

- ↑ Reitsema, H. J.; Hubbard, W. B.; Lebofsky, L. A.; Tholen, D. J. (1982). "Occultation by a Possible Third Satellite of Neptune". Science 215 (4530): 289–291. Bibcode:1982Sci...215..289R. doi:10.1126/science.215.4530.289. PMID 17784355.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 5.11 Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Banfield, D.; Barnet, C.; Basilevsky, A. T.; Beebe, R. F.; Bollinger, K.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A. (1989). "Voyager 2 at Neptune: Imaging Science Results". Science 246 (4936): 1422–1449. Bibcode:1989Sci...246.1422S. doi:10.1126/science.246.4936.1422. PMID 17755997.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Holman, M. J.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Grav, T. et al. (2004). "Discovery of five irregular moons of Neptune" (PDF). Nature 430 (7002): 865–867. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..865H. doi:10.1038/nature02832. PMID 15318214. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Sheppard, Scott S.; Jewitt, David C.; Kleyna, Jan (2006). "A Survey for "Normal" Irregular Satellites around Neptune: Limits to Completeness". The Astronomical Journal 132: 171–176. arXiv:astro-ph/0604552. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..171S. doi:10.1086/504799.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kelly Beatty (2013-07-15). "Neptune's Newest Moon". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- ↑ Flammarion, Camille (1880). Astronomie populaire (in French). p. 591. ISBN 2-08-011041-1.

- ↑ "Camile Flammarion". Hellenica. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. 2006-07-21. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Jewitt, David; Haghighipour, Nader (2007). "Irregular Satellites of the Planets: Products of Capture in the Early Solar System" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 45 (1): 261–95. arXiv:astro-ph/0703059. Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45..261J. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092459.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Miner, Ellis D.; Wessen, Randii R.; Cuzzi, Jeffrey N. (2007). "Present knowledge of the Neptune ring system". Planetary Ring System. Springer Praxis Books. ISBN 978-0-387-34177-4.

- ↑ Horn, Linda J.; Hui, John; Lane, Arthur L.; Colwell, Joshua E. (1990). "Observations of Neptunian rings by Voyager photopolarimeter experiment". Geophysics Research Letters 17 (10): 1745–1748. Bibcode:1990GeoRL..17.1745H. doi:10.1029/GL017i010p01745.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Stooke, Philip J. (1994). "The surfaces of Larissa and Proteus". Earth, Moon, and Planets 65 (1): 31–54. Bibcode:1994EM&P...65...31S. doi:10.1007/BF00572198.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Banfield, Don; Murray, Norm (October 1992). "A dynamical history of the inner Neptunian satellites". Icarus 99 (2): 390–401. Bibcode:1992Icar...99..390B. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90155-Z.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Karkoschka, Erich (2003). "Sizes, shapes, and albedos of the inner satellites of Neptune". Icarus 162 (2): 400–407. Bibcode:2003Icar..162..400K. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00002-2.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Elliot, J. L.; Strobel, D. F.; Zhu, X.; Stansberry, J. A.; Wasserman, L. H.; Franz, O. G. (2000). "The Thermal Structure of Triton's Middle Atmosphere" (PDF). Icarus 143 (2): 425–428. Bibcode:2000Icar..143..425E. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6312.

- ↑ Cruikshank, D.P.; Roush, T.L.; Owen, T.C.; Geballe, TR et al. (1993). "Ices on the surface of Triton". Science 261 (5122): 742–745. Bibcode:1993Sci...261..742C. doi:10.1126/science.261.5122.742. PMID 17757211.

- ↑ Hussmann, Hauke; Sohl, Frank; Spohn, Tilman (November 2006). "Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects". Icarus 185 (1): 258–273. Bibcode:2006Icar..185..258H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Goldreich, P.; Murray, N.; Longaretti, P. Y.; Banfield, D. (1989). "Neptune's story". Science 245 (4917): 500–504. Bibcode:1989Sci...245..500G. doi:10.1126/science.245.4917.500. PMID 17750259.

- ↑ Shaefer, Bradley E.; Tourtellotte, Suzanne W.; Rabinowitz, David L.; Schaefer, Martha W. (2008). "Nereid: Light curve for 1999–2006 and a scenario for its variations". Icarus 196 (1): 225–240. arXiv:0804.2835. Bibcode:2008Icar..196..225S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.02.025.

- ↑ Naeye, R. (September 2006). "Triton Kidnap Caper". Sky & Telescope 112 (3): 18. Bibcode:2006S&T...112c..18N.

- ↑ Naeye, R. (September 2006). "How Moon Mass is Maintained". Sky & Telescope 112 (3): 19. Bibcode:2006S&T...112c..19N.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Agnor, C.B.; Hamilton, D.P. (2006). "Neptune's capture of its moon Triton in a binary-planet gravitational encounter" (PDF). Nature 441 (7090): 192–4. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..192A. doi:10.1038/nature04792. PMID 16688170.

- ↑ Grav, Tommy; Holman, Matthew J.; Fraser, Wesley C. (2004-09-20). "Photometry of Irregular Satellites of Uranus and Neptune". The Astrophysical Journal 613 (1): L77–L80. arXiv:astro-ph/0405605. Bibcode:2004ApJ...613L..77G. doi:10.1086/424997.

- ↑ Thomas, P.C. (2000). "NOTE: The Shape of Triton from Limb Profiles". Icarus 148 (2): 587–588. Bibcode:2000Icar..148..587T. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6511.

- ↑ Davies, Merton E.; Rogers, Patricia G.; Colvin, Tim R. (1991). "A control network of Triton". Journal of Geophysical Research 96 (E1): 15,675–681. Bibcode:1991JGR....9615675D. doi:10.1029/91JE00976.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Jacobson, R.A. (2008). "NEP078 – JPL satellite ephemeris". Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ↑ "Hubble Finds New Neptune Moon". Space Telescope Science Institute. 2013-07-15. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

External links

- Neptune's Moons by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Gazeteer of Planetary Nomenclature—Neptune (USGS)

- Simulation showing the position of Neptune's Moon

- The 13 Moons Of Neptune – Astronoo

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||