Montgomery Place

|

Montgomery Place | |

|

U.S. National Historic Landmark District Contributing Property | |

| |

|

Front (east) elevation, 2008 | |

| |

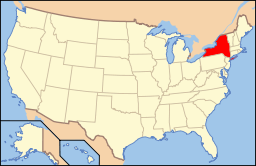

| Location | Annandale-on-Hudson, NY |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Kingston |

| Coordinates | 42°0′52″N 73°55′8″W / 42.01444°N 73.91889°WCoordinates: 42°0′52″N 73°55′8″W / 42.01444°N 73.91889°W |

| Area | 434 acres (176 ha)[1] |

| Built | 1803 |

| Architect | Alexander Jackson Davis; Peter Harris |

| Architectural style | Federal, Italianate |

| Visitation | 30,000[2] (1998[2]) |

| Governing body | Historic Hudson Valley |

| NRHP Reference # | 75001184 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 2, 1975[3] |

| Designated NHL | April 8, 1992[4] |

Montgomery Place, near Barrytown, New York, United States, is an early 19th-century estate that has been designated a National Historic Landmark. It is also a contributing property to the Hudson River Historic District, also a National Historic Landmark.[5] It is a Federal-style house, with expansion designed by architect Alexander Jackson Davis.[6] It reflects the tastes of a younger, post-Revolutionary generation of wealthy landowners in the Livingston family who were beginning to be influenced by French trends in home design, moving beyond the strictly English models exemplified by Clermont Manor a short distance up the Hudson River. It is the only Hudson Valley estate house from this era that survives intact, and Davis's only surviving neoclassical country house.[7]

Andrew Jackson Downing praised the landscapes of the estate, work he had informally consulted on that was not completed in its final form until almost the mid-20th century. The southern 70 acres (28 ha) of the estate, which he called the Wilderness and is today known as the South Woods, is the oldest oak forest in the Hudson Valley.[7] It has grown to 434 acres (176 ha), and includes many outbuildings. A network of trails and paths connects them and offers both quiet wooded tracts and views of the river and Catskill Mountains.

The estate was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. Ten years later, the Livingston descendants sold it to Historic Hudson Valley, a regional historic preservation group.[8] The district was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1990, and Montgomery Place received that designation itself in 1992.[4] Montgomery Place is located on Annandale Road near Barrytown, just off NY 9G. The house and grounds are open to the public; the interior has been open for tours since May 2010. (It was previously closed due to restoration efforts).[9][10] In 2009, the Historic Hudson Valley board considered selling the property.[8]

Property

The estate is bounded on the east by Annandale Road, the north by the Saw Kill and the west by the river. A tree-lined driveway from the road leads west to a visitor center and parking lot next to an orchard. From there it is short walk through a grove of trees to an open lawn in front of the main house, atop a bluff overlooking the river and the Catskill Escarpment across it in the distance.

Five of the 22 buildings, structures and sites identified on the estate have been listed as contributing resources to its historic character. These are the main house, three other Davis-designed buildings and the surviving landscaping.[7]

Main house

The house itself is a two-and-half-story five-by-four-bay building sided in stucco over rubble stone, with two frame wings on the north and south. The latter was originally sanded to give it a stonier appearance. A veranda is on the west (rear) elevation. The metallic hipped roof is pierced by two pairs of brick chimneys on the sides.[1]

All facades are heavily decorated. Swags are on all four chimneys, and balustrades rim most of the roof lines. A central pier on the east above the main entrance is topped with an urn, flanked by wreathed balustrades, a cornice and frieze with triglyphs and metope-ornamented medallions. The double-doored main entrance is flanked by pilasters and topped with a fanlight and ornate keystone. It is sheltered by a semicircular portico supported by fluted Corinthian columns.[1]

A similar portico adorns the rear, with its balustrade also topped by urns. On the wings flat pilasters support a frieze, with columns on the semi octagonal south wing creating an arcade.[1]

The main entrance leads into a rectangular hall with doors leading to the two parlors on either side. It is partly divided by a segmental arch supported by two tapered wooden columns. The library is to the north, with a stair hallway on the south. Much of the decorative woodwork is original.[1]

Outbuildings

Five outbuildings, most of them built around a garden, are in the nearest cluster, south and southwest of the main house. These include the shingle-sided Lodge and its board-and-batten shed, the clapboard-sided Court, a wrought iron greenhouse, and the coach house. This last building is the only outbuilding visible from the main house. It is a flushboard-sided one-and-a-half-story frame house with cross-gabled roof topped by a polygonal cupola. Pilasters mark the corners as well as the flanks of the main building. The interior contains much of the original woodwork.[1]

To the east, close to the road, is the barn complex. It consists of an 1861 barn along with frame structures like the farm office and storage sheds, along with an octagonal stone reservoir building. The board-and-batten farmhouse features a cross-gabled roof and a triple Palladian-style window on the rear.[1]

A group of cottages is located just downhill from the farmhouse. Most are simple frame structures, but one, the Swiss Cottage, was designed by Davis. It features a low-sloping truncated-gabled roof with vergeboard on the roofline and balconies on the rear. The Thompson House also has a dentilled and bracketed cornice.[1]

There are some other isolated outbuildings elsewhere, mostly modern, such as the visitors' center. A cement power station is at the creek mouth, with dams. Some small 20th century cottages are scattered in the orchards. Some buildings described by past visitors to the estate, such as the conservatory, are no longer extant.[1]

Landscapes

The north and south sections of the property, known as the North and South Woods, remain heavily wooded. The South Woods, approximately 70 acres (28 ha) in size, is the oldest oak forest in the Hudson Valley. The North Woods slopes down to the ravine the Saw Kill flows through. Winding paths and trails lead through both wooded tracts. In the North Woods they lead to a waterfall; in the South Woods to the river's edge.

On the east are the property's orchards, leased and operated by Montgomery Place Orchards. On the farm, over 60 different varieties of apple and pear trees are planted and harvested as well as berries, vegetables, grapes and peaches. Annandale Atomic hard cider is also now produced on the farm from early American and English varietal apples. The produce is sold at the Montgomery Place Orchards market. Black locust trees line the 0.5-mile (0.80 km) unpaved allée and surround the lawn of the main house. The lawn on the west of the house slopes down to a reflecting pond at the edge of the wooded shore.

History

Archaeological investigations on the property have revealed evidence of Native American use as a seasonal hunting ground at least 5,000 years ago. These investigations have continued and the area's historic designation reflects its potential in this area as well.[11]

After European settlement in the 18th century, the Saw Kill was used for various mills. Janet Livingston Montgomery purchased 242 acres (98 ha) in the late 1770s, shortly after the death of her husband, General Richard Montgomery, at the Battle of Quebec. The couple had been living in nearby Rhinebeck at the time, where they were building their Grasmere estate, and she moved into that after the Revolutionary War.[7]

She had plans for a Federal style mansion on the riverfront property drawn up and hired a local builder. Naming the house Chateau de Montgomery after her late husband, she moved in after it was completed in 1805. With tree samples her friends sent her from many places near and distant, she established a working farm on the property, employing many slaves and freemen. She lived there until her death in 1828, when the property was bequeathed to her brother.[7]

Edward Livingston had summered there with his wife Louise while he was living in Louisiana, where he had moved after a scandal cost him his jobs as U.S. Attorney for New York and mayor of the city. He had returned to New York and was serving in the House when his sister died. Subsequently he was chosen a Senator and later became the 11th Secretary of State, then as ambassador to France before leaving public service in 1835. They renamed the estate Montgomery Place.[7]

.jpg)

He died the next year, leaving the house to his wife Louise. In 1844 she hired Alexander Jackson Davis to convert the stately mansion into a more ornate villa, in keeping with the era's emerging Romantic sesnsibilities. The two wings and exterior decoration were added at this time. A colonnade on the front entry, the only ornament on the original house, was moved to the interior, one of the only changes to Janet Livingston's original plan.[7]

With the informal help of Andrew Jackson Downing, a friend of Louise's and mentor to Davis, she began developing the landscapes. Her daughter Cora Barton worked with the architect on designing a garden and conservatory. Davis also drew up plans for outbuildings on the estate.[7]

In 1860, upon Louise's death, Cora and her husband hired Davis again to actually build some of the earlier outbuildings. These were the Coach House, Swiss Cottage and farmhouse. They also extended the landscaping. These were part of their overall intent to make the house and its "pleasure grounds" more separate and distinct from the farming operations, which they also began to reduce in scope.[7]

From Cora's relatives it eventually passed to another Livingston descendant, John Ross Delafield, in 1921. He added modern heating and plumbing to the main house. He and his wife, Violetta White Delafield, made the last major additions to the property by extending the landscaping and adding small gardens to it in the years before World War II.[7]

After his death in 1964, his son John White Delafield and his wife moved in. They established two corporations to own and operate the property.[1] In 1975 it was listed on the Register. Eleven years later it was sold for $3 million to Sleepy Hollow Restorations, which later renamed itself Historic Hudson Valley. After a five year and $3 million restoration, the house [7][12] was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1992.

Aesthetics

Janet Livingston's original home reflected the tastes of its era. She and her family derived most of their wealth and prestige from agriculture, leasing lands to tenant farmers. Accordingly their own homes often sat on high ground where they could view their holdings, which in the Livingston family's case included, at that time, portions of the Catskills across the river. The rectilinear forms of the Federal and Greek Revival styles established their authority and dominance of the land.

In the second quarter of the 19th century this began to change. Andrew Jackson Downing of nearby Newburgh championed villa and cottage-style houses in the styles that later came to be known as Carpenter Gothic and Picturesque. These were smaller structures, generally frame, that were topped by steeply pitched, often cross-gabled, roofs with decorated cornices that were intended to harmonize with surrounding natural features, giving the impression of a comfortable place to live. His pattern books sold widely and were used for many houses all over the growing nation.

Janet's descendants called on Downing's friend Alexander Jackson Davis to expand and renovate the house into a more classically-inspired villa over a period of 20 years. He used curved forms in the balustrades and wings to offset the strong vertical lines of the existing building. The arcaded pavilion makes the veranda common on many mid-19th century houses into a wing of its own. Textures were added to the surface in the abundant decorations, many using floral motifs. All these features link the house more firmly to its surrounding landscape. Davis scholar Jane Davies calls it his finest country house.[7]

The farmhouse, too, shows Davis's variations on a popular Downing pattern, "Bracketed Cottage with Veranda", from the posthumously published The Architecture of Country Houses. Davis updated it to the Italianate style more popular at that time, adding the Palladian-style window.[7]

Downing's influence can also be seen in Davis's Swiss Cottage. This pattern, widely republished but rarely built, was varied by Davis, who is not known to have built any other such cottages. He added more entrances since it was expected to have multiple tenants, but four of them are disguised as windows. The essential features of Downing's pattern, such as its floor plan, the low, broad roof; construction into a hillside exposing the basement on one side and multiple galleries and balconies offering views of a nearby stream, remain.[7]

The landscapes were inspired by contemporary European trends. The Bartons had followed Edward Livingston to France when he served there and saw many of Europe's celebrated gardens. Cora Barton had a full set of copies of Joseph Paxton's The Magazine of Botany sent to her when she moved in. Downing, a friend, visited in 1847 and wrote favorably about the resulting landscapes for his own magazine, The Horticulturist. He praised "the deep and mysterious wood" with "dark, intricate and mazy walks" in the "Wilderness" in the north of the property near the Saw Kill. He called it "the most complete estate in America".[7]

Further reading

- Great Houses of the Hudson River, Michael Middleton Dwyer, editor, with preface by Mark Rockefeller, Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company, published in association with Historic Hudson Valley, 2001. ISBN 0-8212-2767-X.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Beebe, Lynn (March 1975). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Montgomery Place". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rozhon, Tracie (August 20, 1998). "From Gehry, A Bilbao on The Hudson". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Montgomery Place". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-15.

- ↑ Neil Larson (September 19, 1990). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Hudson River Historic District" (pdf). National Park Service.

- ↑ Susan Stein, editor (1981). "Montgomery Place Mansion (HABS No. 5627)". Historic American Buildings Survey data pages. Historic American Buildings Survey. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 Haley, Jacquetta (September 19, 1989). "National Historic Landmark application, Montgomery Place". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Strom, Stephanie (November 16, 2009). "A Revolutionary War Widow’s Estate Becomes a Preservation Battleground". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

They decided to turn the house and its grounds, with working orchards and more than a dozen outbuildings, into a museum. So they sold it to what is now Historic Hudson Valley, a nonprofit group founded by John D. Rockefeller Jr. that owns Washington Irving’s house, Sunnyside, in Tarrytown, N.Y., and several other properties.

- ↑ "Montgomery Place". Historic Hudson Valley. 2008. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Montgomery Place listing" hudsonriverheritage.org, retrieved June 29, 2010

- ↑ Historic Hudson Valley brochure available at visitor's center.

- ↑ Melvin, Tessa (May 17, 1987). "Restoration Is Called Key To Protecting Land". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Montgomery Place. |

- Official website

- 13 photos, 1 map, and 11 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- 3 photos, 1 drawing, 3 data pages of Farmhouse at Montgomery Place.

- 2 photos, 1 page of drawings, and 7 data pages, of Swiss Cottage at Montgomery Place, at HABS.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||