Mixing (process engineering)

In industrial process engineering, mixing is a unit operation that involves manipulation of a heterogeneous physical system with the intent to make it more homogeneous. Familiar examples include pumping of the water in a swimming pool to homogenize the water temperature, and the stirring of pancake batter to eliminate lumps (deagglomeration). Mixing is performed to allow heat and/or mass transfer to occur between one or more steams, components or phases. Modern industrial processing almost always involves some form of mixing.[1] Some classes of chemical reactors are also mixers. With the right equipment, it is possible to mix a solid, liquid or gas into another solid, liquid or gas. A biofuel fermenter may require the mixing of microbes, gases and liquid medium for optimal yield; organic nitration requires concentrated (liquid) nitric and sulfuric acids to be mixed with a hydrophobic organic phase; production of pharmaceutical tablets requires blending of solid powders. The opposite of mixing is segregation. A classical example of segregation is the brazil nut effect.

Mixing classification

The type of operation and equipment used during mixing depends on the state of materials being mixed (liquid, semi-solid, or solid) and the miscibility of the materials being processed. In this context, the act of mixing may be synonymous with stirring-, or kneading-processes.[1]

Liquid–liquid mixing

Mixing of liquids is an operation which occurs frequently in process engineering. The nature of the liquid(s) to be blended determines the equipment used for mixing; single-phase blending tends to involve low-shear, high-flow mixers to cause liquid engulfment, while multi-phase mixing generally requires the use of high-shear, low-flow mixers to create droplets of one liquid in laminar, turbulent or transitional flow regimes, depending on the Reynolds number of the flow. Turbulent or transitional mixing is frequently conducted with turbines or impellers; laminar mixing is conducted with helical ribbon or anchor mixers.[2]

Single-phase blending

Mixing of liquids that are miscible or at least soluble in each other occurs frequently in process engineering (and in everyday life). An everyday example would be the addition of milk or cream to tea or coffee. Since both liquids are water-based, they dissolve easily in one another. The momentum of the liquid being added is sometimes enough to cause enough turbulence to mix the two, since the viscosity of both liquids is relatively low. If necessary, a spoon or paddle could be used to complete the mixing process. Blending in a more viscous liquid, such as honey, requires more mixing power per unit volume to achieve the same homogeneity in the same amount of time.

Multi-phase mixing

Mixing of liquids that are not miscible or soluble in each other often necessitates different equipment than is used for single-phase blending. An everyday example would be the mixing of oil into water (or vinegar), which necessitates the use of a whisk or fork rather than a spoon or paddle mixer. Specialized mixers for this purpose, called high shear devices, or HSDs, rotate at high speeds and generate intense shear which breaks up liquid into droplets.

Gas–gas mixing

Solid–solid mixing

Blending powders is one of the oldest unit-operations in the solids handling industries. For many decades powder blending has been used just to homogenize bulk materials. Many different machines have been designed to handle materials with various bulk solids properties. On the basis of the practical experience gained with these different machines, engineering knowledge has been developed to construct reliable equipment and to predict scale-up and mixing behavior. Nowadays the same mixing technologies are used for many more applications: to improve product quality, to coat particles, to fuse materials, to wet, to disperse in liquid, to agglomerate, to alter functional material properties, etc. This wide range of applications of mixing equipment requires a high level of knowledge, long time experience and extended test facilities to come to the optimal selection of equipment and processes.

One example of a solid–solid mixing process is mulling foundry molding sand, where sand, bentonite clay, fine coal dust and water are mixed to a plastic, moldable and reusable mass, applied for molding and pouring molten metal to obtain sand castings that are metallic parts for automobile, machine building, construction or other industries.

Mixing mechanisms

In powder two different dimensions in the mixing process can be determined: convective mixing and intensive mixing. In the case of convective mixing material in the mixer is transported from one location to another. This type of mixing process will lead to a less ordered state inside the mixer, the components which have to be mixed will be distributed over the other components. With progressing time the mixture will become more and more randomly ordered. After a certain mixing time the ultimate random state is reached. Usually this type of mixing is applied for free-flowing and coarse materials. Possible threat during macro mixing is the de-mixing of the components, since differences in size, shape or density of the different particles can lead to segregation. In the convective mixing range, Hosokawa has several processes available from silo mixers to horizontal mixers and conical mixers. When materials are cohesive, which is the case with e.g. fine particles and also with wet material, convective mixing is no longer sufficient to obtain a randomly ordered mixture. The relative strong inter-particle forces will form lumps, which are not broken up by the mild transportation forces in the convective mixer. To decrease the lump size additional forces are necessary; i.e. more energy intensive mixing is required. These additional forces can either be impact forces or shear forces.

Liquid–solid mixing

Liquid–solid mixing is typically done to suspend coarse free-flowing solids, or to break up lumps of fine agglomerated solids. An example of the former is the mixing granulated sugar into water; an example of the latter is the mixing of flour or powdered milk into water. In the first case, the particles can be lifted into suspension (and separated from one another) by bulk motion of the fluid; in the second, the mixer itself (or the high shear field near it) must destabilize the lumps and cause them to disintegrate.

One example of a solid–liquid mixing process in industry is concrete mixing, where cement, sand, small stones or gravel and water are commingled to a homogeneous self-hardening mass, used in the construction industry.

Solid suspension

Suspension of solids into a liquid is done to improve the rate of mass transfer between the solid and the liquid. Examples include dissolving a solid reactant into a solvent, or suspending catalyst particles in liquid to improve the flow of reactants and products to and from the particles. The associated eddy diffusion increases the rate of mass transfer within the bulk of the fluid, and the convection of material away from the particles decreases the size of the boundary layer, where most of the resistance to mass transfer occurs. Axial-flow impellers are preferred for solid suspension, although radial-flow impellers can be used in a tank with baffles, which converts some of the rotational motion into vertical motion. When the solid is denser than the liquid (and therefore collects at the bottom of the tank), the impeller is rotated so that the fluid is pushed downwards; when the solid is less dense than the liquid (and therefore floats on top), the impeller is rotated so that the fluid is pushed upwards (though this is relatively rare). The equipment preferred for solid suspension produces large volumetric flows but not necessarily high shear; high flow-number turbine impellers, such as hydrofoils, are typically used. Multiple turbines mounted on the same shaft can reduce power draw.[3]

Solid deagglomeration

Very fine powders, such as titanium dioxide pigments, and materials that have been spray dried may agglomerate or form lumps during transportation and storage. Starchy materials or those which form gels when exposed to solvent may form lumps which are wetted on the outside but are dry on the inside. These types of materials are not easily mixed into liquid with the types of mixers preferred for solid suspension because the agglomerate particles must be subjected to intense shear to be broken up. In some ways, deagglomeration of solids is similar to the blending of immiscible liquids, except for the fact that coalescence is usually not a problem. An everyday example of this type of mixing is the production of milkshakes from liquid milk and solid ice cream. The type of mixer preferred for solid deagglomeration is a high-shear disperser or a low-power number turbine that can be spun at high speed to produce intense shear fields which rip agglomerates into particles.

Liquid–gas mixing

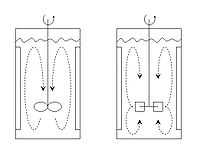

Liquids and gases are typically mixed to allow mass transfer to occur. For instance, in the case of air stripping, gas is used to remove volatiles from a liquid. Typically, a packed column is used for this purpose, with the packing acting as a motionless mixer and the air pump providing the driving force. When a tank and impeller are used, the objective is typically to ensure that the gas bubbles remain in contact with the liquid for as long as possible. This is especially important if the gas is expensive, such as pure oxygen, or diffuses slowly into the liquid. Mixing in a tank is also useful when a (relatively) slow chemical reaction is occurring in the liquid phase, and so the concentration difference in the thin layer near the bubble is close to that of the bulk. This reduces the driving force for mass transfer. If there is a (relatively) fast chemical reaction in the liquid phase, it is sometimes advantageous to disperse but not recirculate the gas bubbles, ensuring that they are in plug flow and can transfer mass more efficiently.

Rushton turbines have been traditionally used do disperse gases into liquids, but newer options, such as the Smith turbine and Bakker turbine are becoming more prevalent.[4] One of the issues is that as the gas flow increases, more and more of the gas accumulates in the low pressure zones behind the impeller blades, which reduces the power drawn by the mixer (and therefore its effectiveness). Newer designs, such as the GDX impeller, have nearly eliminated this problem.

Gas–solid mixing

Gas–solid mixing may be conducted to transport powders or small particulate solids from one place to another, or to mix gaseous reactants with solid catalyst particles. In either case, the turbulent eddies of the gas must provide enough force to suspend the solid particles, which will otherwise sink under the force of gravity. The size and shape of the particles is an important consideration, since different particles will have different drag coefficients, and particles made of different materials will have different densities. A common unit operation the process industry to separate gases and solids is the cyclone which slows the gas and causes the particles to settle out.

Multiphase mixing

Multiphase mixing occurs when solids, liquids and gases are combined in one step. This may occur as part of a catalytic chemical process, in which liquid and gaseous reagents must be combined with a solid catalyst (such as hydrogenation); or in fermentation, where solid microbes and the gases they require must be well-distributed in a liquid medium. The type of mixer used depends upon the properties of the phases. In some cases, the mixing power is provided by the gas itself as it moves up through the liquid, entraining liquid with the bubble plume. This draws liquid upwards inside the plume, and causes liquid to fall outside the plume. If the viscosity of the liquid is too high to allow for this (or if the solid particles are too heavy), an impeller may be needed to keep the solid particles suspended.

Constitutive equations

Many of the equations used for determining the output of mixers are empirically derived, or contain empirically-derived constants. Since mixers operate in the turbulent regime, many of the equations are approximations that are considered acceptable for most engineering purposes.

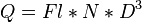

When a mixing impeller rotates in the fluid, it generates a combination of flow and shear. The impeller generated flow can be calculated with the following equation:

Flow numbers for impellers have been published in the North American Mixing Forum sponsored Handbook of Industrial Mixing.[5]

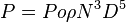

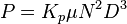

The power required to rotate an impeller can be calculated using the following equations:

(Turbulent regime)[6]

(Turbulent regime)[6]

(Laminar regime)

(Laminar regime)

is the (dimensionless) power number, which is a function of impeller geometry;

is the (dimensionless) power number, which is a function of impeller geometry;  is the density of the fluid;

is the density of the fluid;  is the rotational speed, typically rotations per second;

is the rotational speed, typically rotations per second;  is the diameter of the impeller;

is the diameter of the impeller;  is the laminar power constant; and

is the laminar power constant; and  is the viscosity of the fluid. Note that the mixer power is strongly dependent upon the rotational speed and impeller diameter, and linearly dependent upon either the density or viscosity of the fluid, depending on which flow regime is present. In the transitional regime, flow near the impeller is turbulent and so the turbulent power equation is used.

is the viscosity of the fluid. Note that the mixer power is strongly dependent upon the rotational speed and impeller diameter, and linearly dependent upon either the density or viscosity of the fluid, depending on which flow regime is present. In the transitional regime, flow near the impeller is turbulent and so the turbulent power equation is used.

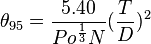

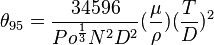

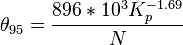

The time required to blend a fluid to within 5% of the final concentration,  , can be calculated with the following correlations:

, can be calculated with the following correlations:

(Turbulent regime)

(Turbulent regime)

(Transitional region)

(Transitional region)

(Laminar regime)

(Laminar regime)

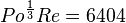

The Transitional/Turbulent boundary occurs at

The Laminar/Transitional boundary occurs at

Laboratory mixing

At a laboratory scale, mixing is achieved by magnetic stirrers or by simple hand-shaking. Sometimes mixing in laboratory vessels is more thorough and occurs faster than is possible industrially. Magnetic stir bars are radial-flow mixers that induce solid body rotation in the fluid being mixed. This is acceptable on a small scale, since the vessels are small and mixing therefore occurs rapidly (short blend time). A variety of stir bar configurations exist, but because of the small size and (typically) low viscosity of the fluid, it is possible to use one configuration for nearly all mixing tasks. The cylindrical stir bar can be used for suspension of solids, as seen in iodometry, deagglomeration (useful for preparation of microbiology growth medium from powders), and liquid–liquid blending. Another peculiarity of laboratory mixing is that the mixer rests on the bottom of the vessel instead of being suspended near the center. Furthermore, the vessels used for laboratory mixing are typically more widely varied than those used for industrial mixing; for instance, Erlenmeyer flasks, or Florence flasks may be used in addition to the more cylindrical beaker.

Mixing in microfluidics

When scaled down to the microscale, fluid mixing behaves radically different.[7] This is typically at sizes from a couple (2 or 3) millimeters down to the nanometer range. At this size range normal convection does not happen unless you force it. Diffusion is the dominate mechainism whereby two different fluids come together. Diffusion is a relatively slow process. Hence a number of researchers had to devise ways to get the two fluids to mix. This involved Y junctions, T junctions, three-way intersections and designs where the interfacial area between the two fluids is maximized. Beyond just interfacing the two liquids people also made twisting channels to force the two fluids to mix. These included multilayered devices where the fluids would corkscrew, looped devices where the fluids would flow around obstructions and wavy devices where the channel would constrict and flare out. Additionally channels with features on the walls like notches or groves were tried.

One way to tell if mixing is happening due to convection or diffusion is by finding the Peclet number. It is the ratio of convection to diffusion. At high Peclet numbers, convection dominates. At low Peclet numbers, diffusion dominates.

Peclet = flow velocity * mixing path / diffusion coefficient

Industrial mixing equipment

At an industrial scale, efficient mixing can be difficult to achieve. A great deal of engineering effort goes into designing and improving mixing processes. Mixing at industrial scale is done in batches (dynamic mixing), inline or with help of static mixers. Moving mixers are powered with electric motors which operate at standard speeds of 1800 or 1500 RPM, which is typically much faster than necessary. Gearboxes are used to reduce speed and increase torque. Some applications require the use of multi-shaft mixers, in which a combination of mixer types are used to completely blend the product.[8]

Turbines

A selection of turbine geometries and power numbers are shown below.

| Name | Power number | Flow direction | Blade angle (degrees) | Number of blades | Blade geometry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rushton turbine | 4.6 | Radial | 0 | 6 | Flat |

| Pitched blade turbine | 1.3 | Axial | 45–60 | 3–6 | Flat |

| Hydrofoil | 0.3 | Axial | 45–60 | 3–6 | Curved |

| Marine Propeller | 0.2 | Axial | N/A | 3 | Curved |

Different types of impellers are used for different tasks; for instance, Rushton turbines are useful for dispersing gases into liquids, but are not very helpful for dispersing settled solids into liquid. Newer turbines have largely supplanted the Rushton turbine for gas–liquid mixing, such as the Smith turbine and Bakker turbine.[9] The power number is an empirical measure of the amount of torque needed to drive different impellers in the same fluid at constant power per unit volume; impellers with higher power numbers will require more torque but operate at lower speed than impellers with lower power numbers, which will operate at lower torque but higher speeds.

Close-clearance mixers

There are two main types of close-clearance mixers: anchors and helical ribbons. Anchor mixers induce solid-body rotation and do not promote vertical mixing, but helical ribbons do. Close clearance mixers are used in the laminar regime, because the viscosity of the fluid overwhelms the inertial forces of the flow and prevents the fluid leaving the impeller from entraining the fluid next to it. Helical ribbon mixers are typically rotated to push material at the wall downwards, which helps circulate the fluid and refresh the surface at the wall.[10]

High shear dispersers

High shear dispersers create intense shear near the impeller but relatively little flow in the bulk of the vessel. Such devices typically resemble circular saw blades and are rotated at high speed. Because of their shape, they have a relatively low drag coefficient and therefore require comparatively little torque to spin at high speed. High shear dispersers are used for forming emulsions (or suspensions) of immiscible liquids and solid deagglomeration.[11]

Static mixers

Static mixers are used when a mixing tank would be too large, too slow, or too expensive to use in a given process.

See also

- Banbury mixer

- Industrial mixer

References

For an in-depth resource covering mixing theory, technology, and a very broad range of applications please refer to the Handbook of Industrial Mixing: Science and Practice.[5]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ullmann, Fritz (2005). Ullmann's Chemical Engineering and Plant Design, Volumes 1–2. John Wiley & Sons. http://app.knovel.com/hotlink/toc/id:kpUCEPDV02/ullmanns-chemical-engineering

- ↑ http://www.bakker.org/cfm/webdoc13.htm

- ↑ http://www.bakker.org/cfm/webdoc4.htm

- ↑ http://cercell.com/support/bactovessel-details/turbine-principles/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Edward L. Paul, Victor Atiemo-Obeng, and Suzanne M. Kresta, ed. (2003). Handbook of Industrial Mixing: Science and Practice. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-26919-9.

- ↑ http://cercell.com/support/bactovessel-details/turbine-power/

- ↑ Nguyen, Nam-Trung; Wu, Zhigang (1 February 2005). "Micromixers—a review". Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 15 (2): R1–R16. Bibcode:2005JMiMi..15R...1N. doi:10.1088/0960-1317/15/2/R01.

- ↑ http://www.hockmeyer.com/products/high-viscosity-mixers/dual-triple-shaft-mixer-detail.html

- ↑ http://www.bakker.org/cfm/bt6.htm

- ↑ http://www.bakker.org/cfm/webdoc10.htm

- ↑ http://www.hockmeyer.com/technical/publications/73-dispersion-tips-help.html