Mitch Daniels

| Mitch Daniels | |

|---|---|

| |

| 12th President of Purdue University | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office January 14, 2013 | |

| Preceded by | Timothy Sands (Acting) |

| 49th Governor of Indiana | |

| In office January 10, 2005 – January 14, 2013 | |

| Lieutenant | Becky Skillman |

| Preceded by | Joe Kernan |

| Succeeded by | Mike Pence |

| Director of the Office of Management and Budget | |

| In office January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2003 | |

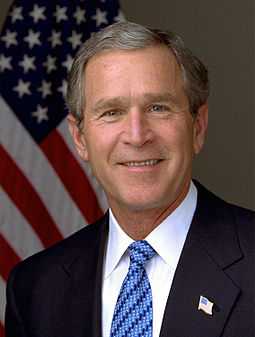

| President | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Jacob Lew |

| Succeeded by | Joshua Bolten |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mitchell Elias Daniels, Jr. April 7, 1949 Monongahela, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Cheri Herman (1978–1993; 1997–present) |

| Alma mater | Princeton University Georgetown University |

| Religion | Presbyterianism |

| Signature | |

| Website | Purdue University website Government website |

Mitchell Elias "Mitch" Daniels, Jr. (born April 7, 1949) is an American academic administrator and former politician who was Governor of Indiana from 2005 to 2013. He is a member of the Republican Party. Since 2013, Daniels has been President of Purdue University.

Born in Monongahela, Pennsylvania, Daniels is a graduate of Princeton University, studied briefly at the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law and received his Juris Doctor from Georgetown University Law Center. Daniels began his career working as an assistant to Richard Lugar, working as his Chief of Staff in the Senate from 1977 to 1982, and was appointed Executive Director of the National Republican Senatorial Committee when Lugar was Chairman from 1983 to 1984. He worked as a chief political adviser and as a liaison to President Ronald Reagan in 1985, before he was appointed President of the conservative think tank, the Hudson Institute. Daniels moved back to Indiana, joining Eli Lilly and Company, working as President of North American Pharmaceutical Operations from 1993 to 1997, and Senior Vice President of Corporate Strategy and Policy from 1997 to 2001. In January 2001, Daniels was appointed by President George W. Bush as the Director of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, where he served until June 2003.

Daniels announced his intention to run in Indiana's 2004 gubernatorial election after leaving the Bush administration. He won the Republican primary with 67% of the vote, and defeated Democratic incumbent Governor Joe Kernan in the general election. Daniels was reelected to a second term, defeating former U.S. Representative and US Department of Agriculture undersecretary Jill Long Thompson, on November 4, 2008. During his tenure as governor, Daniels cut the state government workforce by 18%, cut and capped state property taxes, and balanced the state budget through budget austerity measures and increasing spending by less than the inflation rate.[1][2] In his second term, Daniels saw protest by labor unions and Democrats in the state legislature over his policies regarding the Indiana's school voucher program and the Indiana House of Representatives attempt to pass right to work legislation, leading to the 2011 Indiana legislative walkouts. During the legislature's last session under Daniels, he signed the state's controversial right-to-work law; with Indiana becoming the 23rd state in the nation to do so.[3]

It was widely speculated that Daniels would be a candidate in the 2012 presidential election,[4][5][6] but he chose not to run.[7] He is the author of the best selling book Keeping the Republic: Saving America by Trusting Americans. Daniels was selected to be President of Purdue University after his term as Governor ended on January 14, 2013.

Early life

Family and education

Mitchell Elias Daniels, Jr., was born on April 7, 1949 in Monongahela, Pennsylvania, the son of Dorothy Mae (née Wilkes) and Mitchell Elias Daniels, Sr.[8] His father's parents were immigrants from Syria, of Eastern Orthodox Christian descent.[9] Daniels has been honored by the Arab-American Institute with the 2011 Najeeb Halaby Award for Public Service.[10][11][12] His mother's ancestry was mostly English (where three of his great-grandparents were born), as well as Scottish and Welsh.[13] Daniels spent his early childhood years in Pennsylvania, Tennessee,[14] and Georgia.

The Daniels family moved to Indiana from Pennsylvania in 1959 when his father accepted a job at the Indianapolis headquarters of the pharmaceutical company Pittman-Moore. Then 11-year-old Daniels was accustomed to the mountains, and he at first disliked the flatland of central Indiana. He was still in grade school at the time of the move and first attended Delaware Trail Elementary, Westlane Junior High School, and North Central High School. In high school he was student body president.[15] After graduation in 1967, Daniels was named one of Indiana's Presidential Scholars—the state’s top male high school graduate that year—by President Lyndon B. Johnson.[16]

In 1971, Daniels earned a Bachelor's degree from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. While there, he was a member of the American Whig–Cliosophic Society, where he overlapped with future Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito, who was a year below. He initially studied law at the Indiana McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis. After accepting a job with newly elected Senator Richard Lugar, he transferred to the Georgetown University Law Center, from which he earned a Juris Doctor.[11]

In 1970, while an undergraduate student at Princeton, a grand jury indicted Daniels for marijuana possession and for maintaining a common nuisance.[17] The charges were eventually dropped and Daniels pled guilty to “a disorderly person charge” based on a confession that he had used marijuana. He spent two nights in jail and paid a $350 fine.[18] According to Daniels roommate at the time, police obtained a warrant to search the room based on the activity of another student who used to live in the room. The roommate told the Daily Princetonian that “Unbeknownst to [Daniels and the other current roommates]…[the former roommate] was coming back there and using the room when we’re not there and was involved with drugs much worse than pot.” [17] Daniels told The Daily Princetonian in 2011 that "justice was served,"[19] and has disclosed the arrest on job applications, and spoken about the incident in columns in The Indianapolis Star[20] and The Washington Post.[21]

In February 2013, Princeton honored Daniels with the Woodrow Wilson Award, which recognizes an alumnus whose career embodies the call to duty in Wilson's famous speech, "Princeton in the Nation's Service." The award was presented during Alumni Day activities on February 23, 2013.

Early political career

Daniels had his first experience in politics while still a teenager when, in 1968, he worked on the unsuccessful campaign of fellow Hoosier and Princeton alumnus William Ruckelshaus, who was running for the U.S. Senate against incumbent Democrat Birch Bayh.[15] After the campaign Ruckelshaus helped Daniels secure an internship in the office of then-Indianapolis mayor Richard Lugar. Daniels worked on Lugar's re-election campaign in 1971, and later, in 1974, he worked on Lugar's first campaign for Senate via L. Keith Bulen's Campaign Communicators, Inc, a political consultancy where Daniels served as vice president. Daniels joined Lugar's mayoral staff in December, 1974.[22] Within three years, he became Lugar's principal assistant. After Lugar was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1976, Daniels followed him to Washington, D.C. as his Chief of Staff.[20]

Daniels served as Chief of Staff during Lugar's first term (1977–82); and, during this time, he met Cheri Herman, who was working for the National Park Service. The two married in 1978 and had four daughters. They divorced in 1993 and Cheri married again; Cheri later divorced her second husband and remarried Daniels in 1997.[11]

In 1983, when Lugar was elected Chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, Daniels was appointed its Executive Director. Serving in that position (1983–84), he played a major role in keeping the GOP in control of the Senate. Daniels was also manager of three successful re-election campaigns for Lugar. In August 1985, Daniels became chief political advisor and liaison to President Ronald Reagan.[20]

In 1987, Daniels returned to Indiana as President and CEO of the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank.[11][23] In 1988, Dan Quayle was elected Vice President of the United States, and Governor of Indiana Robert D. Orr offered to appoint Daniels to Quayle's vacant Senate seat. Daniels declined the offer, saying it would force him to spend too much time away from his family.[15]

Eli Lilly

In 1990, Daniels left the Hudson Institute to accept a position at Eli Lilly and Company, the largest corporation headquartered in Indiana at that time.[24] He was first promoted to President of North American Operations (1993–97) and then to Senior Vice President for Corporate Strategy and Policy (1997–2001).[10][11][20] During his time at Lilly, Daniels managed a successful strategy to deflect attacks on Lilly's Prozac product by a public relations campaign against the drug being waged by the Church of Scientology. In one interview in 1992, Daniels said of the organization that "it is no church," and that people on Prozac were less likely to become victims of the organization. The Church of Scientology responded by suing Daniels in a libel suit for $20 million. A judge dismissed the case.[25]

Eli Lilly experienced dramatic growth during Daniels' tenure at the company. Prozac sales made up 30–40% of Lilly's income during the mid-to-late 1990s, and Lilly doubled its assets to $12.8 billion and doubled its revenue to $10 billion during the same period. When Daniels later became Governor of Indiana, he drew heavily on his former Lilly colleagues to serve as advisers and agency managers.[26]

During the same period, Daniels also served on the board of directors of the Indianapolis Power & Light (IPL). He resigned from the IPL Board in 2001 to join the federal government, and sold his IPL stock for $1.45 million. Later that year the value declined when Virginia-based AES Corporation bought IPL.[10] The Indiana Securities Division subsequently investigated the sale and found no wrongdoing, but opponents brought up the sale and questioned it during his later election campaign.[25]

Office of Management and Budget

In January 2001, Daniels accepted President George W. Bush's invitation to serve as director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). He served as Director from January 2001 through June 2003. In this role he was also a member of the National Security Council and the Homeland Security Council.

During his time as the director of the OMB, Bush referred to him as "the Blade," for his noted acumen at budget cutting.[27] The $2.13 trillion budget Daniels submitted to Congress in 2001 would have made deep cuts in many agencies to accommodate the tax cuts being made, but few of the spending cuts were actually approved by Congress.[15] During Daniels' 29-month tenure in the position, the projected federal budget surplus of $236 billion declined to a $400 billion deficit, due to an economic downturn, and failure to enact spending cuts to offset the tax reductions.[20]

Shortly after the invasion of Afghanistan, Daniels gave a speech to the National Press Club in which he challenged the view of those who wanted to continue typical spending while the nation was at war. “The idea of reallocating assets from less important to more important things, especially in a time of genuine emergency, makes common sense and is applied everywhere else in life,” he said.[28]

Conservative columnist Ross Douthat stated in a column about Daniels time at OMB that Daniels "carried water, as director of the Office of Management and Budget, for some of the Bush administration’s more egregious budgets."[29] But Douthat, while calling Daniels “America’s Best Governor,” defended Daniels against accusations that Daniels inaccurately assessed the costs of the Iraq war.[30]

In the final days of 2002, when an invasion of Iraq was still a hypothetical question, Daniels told the New York Times that the cost of war with Iraq “could be” in the range of $50 to $60 billion. It was not clear whether Daniels was referring to the cost of a short invasion or a longer war, but he did indicate the administration was budgeting for both. He also described the “back-of-the-envelope” estimate by Bush Economic Advisor Lawrence B. Lindsey that it would cost $100 to $200 billion as much too high.[31] Two days later, after the New Years Holiday, an OMB spokesperson clarified Daniels’ remarks, adding that the $50 to $60 billion figure was not a hard White House estimate and “it is impossible to know what any military campaign would ultimately cost. The only cost estimate we know of in this arena is the Persian Gulf War and that was a $60 billion event".[32]

Three months later, on March 25, 2003, five days after the start of the invasion, President Bush requested $53 billion through an emergency supplemental appropriation to cover operational expenses in Iraq until September 30 of that year.[33] According to the Congressional Budget Office, Military operations in Iraq for 2003 cost $46 Billion, less than the amount projected by Daniels and OMB.[34] Douthat and other Daniel’s defenders accuse Daniels' critics of mischaracterizing the six-month supplemental appropriation as a request to fund the entire war.[29][30]

Between September 2001 and October 2012, lawmakers appropriated about $1.4 trillion for operations in both the war in Iraq and Afghanistan.[35]

Governor

Election campaign

Daniels' decision to run for Governor of Indiana led to most of the rest of Republican field of candidates to drop out of the race. The only challenger who did not do so was conservative activist and lobbyist Eric Miller. Miller worked for the Phoenix Group, a Christian rights defense group. Daniels' campaign platform centered around cutting the State budget and privatizing public agencies. He won the primary with 67% of the vote.[36]

While campaigning in the General Election, Daniels visited all 92 Counties at least three times. He traveled in a donated white RV nicknamed "RV-1" and covered with signatures of supporters and his campaign slogan, "My Man Mitch."[37] "My Man Mitch" was a reference to a phrase once used by President George W. Bush to refer to Daniels. Bush campaigned with Daniels on two occasions, as Daniels hoped that Bush's popularity would help him secure a win. In his many public stops, he frequently used the phrase "every garden needs weeding every sixteen years or so"; it had been 16 years since Indiana had had a Republican governor.[36] His opponent in the general election was the incumbent, Joe Kernan, who had succeeded to the office upon the death of Frank O'Bannon. Campaign ads by Kernan and the Democratic Party attempted to tie Daniels to number of issues—his jail time for marijuana use; a stock sale leading to speculations of insider trading; and, because of his role at Eli Lilly, the high cost of prescription drugs.[37] The 2004 election was the costliest in Indiana history, up until that time, with the candidates spending a combined US$23 million.[36] Daniels won the election, garnering about 53% of the vote compared to Kernan's 46%.[36] Kernan was the first incumbent Governor to lose an election in Indiana since 1892.[36]

First term

On his first day in office, Daniels created Indiana's first Office of Management and Budget to look for inefficiencies and cost savings throughout state government. The same day, he decertified all government employee unions by executive order, removing the requirement that state employees pay union dues by rescinding a mandate created by Governor Evan Bayh in a 1989 executive order. Dues-paying union membership subsequently dropped 90% among state employees.[38][39]

Budgetary measures

In his first State of the State address on January 18, 2005, Daniels put forward his agenda to improve the State's fiscal situation. Indiana has a biennial budget, and had a projected two-year deficit of $800 million. Daniels called for strict controls on all spending increases, and reducing the annual growth rate of the budget. He also proposed a one-year 1% tax increase on all individuals and entities earning over $100,000. The taxing proposal was controversial and the Republican Speaker of the House, Brian Bosma, criticized Daniels and refused to allow the proposal to be debated.[36][40]

The General Assembly approved $250 million in spending cuts and Daniels renegotiated 30 different state contracts for a savings of $190 million, resulting in a budget of $23 billion. Annual spending growth for future budgets was cut to 2.8% from the 5.9% that had been standard for many years.[40][41] Increase in revenues, coupled with the spending reductions, led to a $300 million budget surplus. Indiana is not permitted to take loans, as borrowing was prohibited in its constitution following the 1837 state bankruptcy. The state, therefore, had financed its deficit spending by reallocating $760 million in revenue that belonged to local government and school districts over the course of many years. The funds were gradually and fully restored to the municipal governments using the surplus money, and the state reserve fund was grown to $1.3 billion.[41]

Two of Daniels' other tax proposals were approved: a tax on liquor and beverages to fund the construction of the Lucas Oil Stadium and a tax on rental cars to expand the Indiana Convention Center. The new source of funding resulted in a state take-over of a project initially started by the City of Indianapolis and led to a bitter feud between Daniels and the city leadership over who should have ownership of the project. The state ultimately won and took ownership of the facilities from the city.[42]

In 2006, Daniels continued his effort to reduce state operating costs by signing into law a bill privatizing the enrollment service for the state's welfare programs. Indiana's welfare enrollment facilities were replaced with call centers operated by IBM. In mid-2009, after complaints of poor service, Daniels canceled the contract and returned the enrollment service to the public sector.[30]

Daylight Saving Time

One of the most controversial measures Daniels successfully pushed through was the state adoption of Daylight Saving Time, which Daniels argued would save the state money on energy costs.[42] Although the state is in the Eastern Time Zone, Indiana's counties had adopted their own time zone practices, and in practice the state effectively observed two different times, and the central part of the state maintained a single time—Eastern Standard—year round.[42] Interests for both EST and CST time zones had prevented the official adoption of daylight saving since the 1930s, and had led to decades of debate. Daniels pressed for the entire state to switch to Central Time, but the General Assembly could not come to terms. Ultimately after a long debate, they adopted Eastern Daylight Saving Time in April 2005, the measure passing by one vote, putting all but northwestern and southwestern Indiana on the same time for the first time.[42]

Highways

A controversial plan, known as the Major Moves plan, was passed in 2006. The Indiana Toll Road was leased to Statewide Mobility Partners, a joint venture company owned by Spanish firm Cintra and Australia's Macquarie Infrastructure Group for 75 years in exchange for a one time payment of $3.85 billion. The measure was opposed by most Democrats, who began an advertising campaign accusing Daniels of selling the road to foreign nations.[43][44] The income from the lease was used to finance a backlog of public transportation projects and create a $500 million trust fund to generate revenue for the maintenance of the highway system.[41]

Daniels' support for such controversial legislation led to a rapid drop in his approval rating; in May 2005, a poll showed an 18-point drop in support and that only 42% of Hoosiers approved of the way he was doing his job. In the following months, many of his reforms began to have a positive effect; and his ratings began to improve, and his approval rebounded.[45]

Economic development

When Daniels was elected, he stated his number one priority was job creation.[10] To achieve that goal, he created the public-private Indiana Economic Development Corporation (IEDC), became chairman of its board, and ordered it to “act at the speed of business, not the speed of government,” to attract new jobs. During its first year, the IEDC closed more transactions than similar efforts had during the previous two years combined. Between 2005 and 2008, 485 businesses committed to creating more than 60,000 new jobs and invest $14.5 billion into the Indiana economy.[10]

During a 12-day trade mission in Asia, Daniels visited Indiana soldiers serving on the border of the Korean Demilitarized Zone. On the 56th anniversary of the start of the Korean War, he laid a bouquet of white flowers at the base of a plaque listing 900 soldiers from Indiana who died in the war. During the visit he met with Asian auto executives and successfully promoted the expansion of facilities in Indiana.[46]

In 2006, the IEDC topped its 2005 results. It landed three high profile automotive investments from Toyota, Honda, and Cummins. In 2007, the IEDC announced its third consecutive record-breaking year for new investment and job commitments in Indiana with its largest deal being made with BP to construct $3.2 billion in facilities to assist in recovery of fuel from the Canadian tar sands.[10][41]

Healthy Indiana Plan

In 2007, Daniels signed the Healthy Indiana Plan, which provided 132,000 uninsured Indiana workers with coverage. The program works by helping its beneficiaries purchase a private health insurance policy with a subsidy from the state. The plan promotes health screenings, early prevention services, and smoking cessation. It also provides tax credits for small businesses that create qualified wellness and Section 125 plans. The plan was paid for by an increase in the state’s tax on cigarettes and the reallocation of federal medicaid funds through a special wavier granted by the federal government. In a September 15, 2007 Wall Street Journal column, Daniels was quoted as saying about the Healthy Indiana Plan and cigarette tax increase saying, “A consumption tax on a product you'd just as soon have less of doesn't violate the rules I learned under Ronald Reagan."[47]

The plan allows low to moderate income households where the members have no access to employer provided healthcare to apply for coverage. The fee for coverage is calculated using a formula that results in a charge between 2%–5% of a person's income. A $1,100 annual deductible is standard on all policies and allows applicants to qualify for a health savings account. The plan pays a maximum of $300,000 in annual benefits.[48]

WGU Indiana

Western Governor's University of Indiana is the eighth university in Indiana and was formed with the support of Gov. Mitch Daniels in 2010.[49] The purpose of the new on-line university is to increase education opportunities for working adults across Indiana. In December 2012 WGU Indiana celebrated its 500th graduate.[50]

Property tax reform

In 2008, Daniels proposed a property tax ceiling of one percent on residential properties, two percent for rental properties and three percent for businesses. The plan was approved by the Indiana General Assembly on March 14, 2008 and signed by Daniels on March 19, 2008. In 2008, Indiana homeowners had an average property tax cut of more than 30 percent; a total of $870 million in tax cuts. Most money collected through property taxes funds local schools and county government. To offset the loss in revenues to the municipal bodies, the state raised the sales tax from 6% to 7% effective April 1, 2008.[51]

Fearing a future government may overturn the statute enforcing property tax rate caps, Daniels and other state Republican leaders pressed for an amendment to add the new tax limits to the state constitution. The proposed amendment was placed on the 2010 General election ballot and was a major focus of Daniels' reelection campaign. In November 2010, voters elected to adopt the tax caps into the Indiana Constitution.[52]

Daniels' successes at balancing the state budget began to be recognized nationally near the end of his first term. Daniels was named on the 2008 "Public Officials of the Year" by the Governing magazine.[53] The same year, he received the 2008 Urban Innovator Award from the Manhattan Institute for his ideas for dealing with the state's fiscal and urban problems.[54]

Voter registration

In the 2005 session of the General Assembly, Daniels and Republicans, with some Democratic support, successfully enacted a voter registration law that required voters to show a government issued photo ID before they could be permitted to vote. The law was the first of its kind in the United States, and many civil rights organizations, like the ACLU, opposed the bill saying it would unfairly impact minorities, poor, and elderly voters who may be unable to afford an ID or may be physically unable to apply for an ID. To partially address those concerns, the state passed another law authorizing state license branches to offer free state photo ID cards to individuals who did not already possess another type of state ID.[55]

A coalition of civil rights groups began a court challenge of the bill in Indiana state courts, and the Daniels' administration defended the government in the case. The Indiana Supreme Court ruled in favor of the state in late 2007. The petitioners appealed the bill to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, and that body upheld the State Supreme Court decision in the case of Crawford v. Marion County Election Board. Upon appeal the United States Supreme Court also ruled in favor of the state in April 2008, setting a legal precedent. Several other states subsequently enacted similar laws in the years following.[55]

Reelection campaign

Daniels entered the 2008 election year with a 51% approval rate, and 28% disapproval rate. Daniels' reelection campaign focused on the states unemployment rate, which had lowered during his time in office, the proposed property tax reform amendment, and the successful balancing of the state budget during his first term.[56]

On November 4, 2008, Daniels defeated Democratic candidate Jill Long Thompson and was elected to a second term as Governor with 57.8% of votes.[57] He was reinaugurated on January 12, 2009. Washington Post blogger Chris Cillizza named the Daniels reelection campaign "The Best Gubernatorial Campaign of 2008" and noted that some Republicans were already bandying about his name for the 2012 presidential election.[58] Daniels garnered 20 percent of the African American vote and 37 percent of Latinos in his 2008 re-election campaign. He won with more votes than any candidate in the state's history.

On July 14, 2010 at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Daniels was on hand to help announce the return of IndyCar Series chassis manufacturing to the state of Indiana.[59] Dallara Automobili will build a new technology center in Speedway, Indiana and the state of Indiana will subsidize the sale of the first 28 IndyCar chassis with a $150,000 discount.[60]

Daniels has been recognized for his commitment to fiscal discipline. He is a recent recipient of the Herman Kahn Award from the conservative think tank the Hudson Institute, of which he is a former President and CEO, and was one of the first to receive the Fiscy award for fiscal discipline.[61] A November 2010 poll gave Daniels a 75% approval rate.[62]

Second term

Democrats won a majority in the Indiana House of Representatives in the 2006 and 2008 elections. This caused Indiana to have a divided government, with Democrats controlling the Indiana House of Representatives and the Republicans controlling the Governor's office and the Indiana Senate. This also lead to a stalemate in the budget debate, which caused Mitch Daniels call a special session of the Indiana General Assembly. The state was faced with a $1 billion shortfall in revenue for the 2009–11 budget years. Daniels proposed a range of spending cuts and cost-saving measures in his budget proposal. The General Assembly approved some of his proposals, but relied heavily on the state's reserve funds to pay for the budget shortfall. Daniels signed the $27 billion two-year budget into law.

2011 legislative walkout

In the 2010 mid-term elections, Republican super-majorities regained control of the House, and took control of the Senate, giving the party full control of General Assembly for the first time in Daniels' tenure as governor. The 2011 Indiana General Assembly's regular legislative session began in January and the large Republicans majorities attempted to implement a wide-ranging conservative agenda largely backed by Daniels. Most of the agenda had been "dormant" since Daniels' election due to divided control of the assembly.[63] In February, Republican legislators attempted to pass a right to work bill in the Indiana House of Representatives. The bill would have made it illegal for employees to be required to join a workers' union. Republicans argued that it would help the state attract new employers. Unable to prevent the measure from passing, Democratic legislators fled the state to deny the body quorum while several hundred protesters staged demonstrations at the capital. Minority walkouts are somewhat common in the state, occurring as recently as 2005.[64]

While Daniels supported the legislation, he believed the Republican lawmakers should drop the bill because it was not part of their election platform and deserved a period of public debate. Republicans subsequently dropped the bill, but the Democratic lawmakers still refused to return to the capital, demanding additional bills be tabled, including a bill to create a statewide school voucher program. Their refusal to return left the Indiana General Assembly unable to pass any legislation, until three of the twelve bills they objected to were dropped from the agenda on March 28. The minority subsequently returned to the statehouse to resume their duties.[64]

Daniels was interviewed in February 2011 about the similar 2011 Wisconsin budget protests in Madison. While supporting the Wisconsin Republicans, he said that in Indiana "we're not in quite the same position or advocating quite the same things they are up in Madison."[65]

Education

Following the legislative walkouts, the assembly began passing most of the agenda and Daniels signed the bills into law. Written in collaboration with Indiana Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Bennett, a series of education reform laws made a variety of major changes to statewide public schools. A statewide school voucher program was enacted. Children in homes with an income under $41,000 could receive vouchers equal to 90% of the cost of their public school tuition and use that money to attend a private school. It provides lesser benefits to households with income over $41,000. The program will be gradually phased in over a three-year period and would be available to all state residents by 2014.[63][66][67]

Other funds were redirected to creating and expanding charter schools, and expanding college scholarship programs. The law also created a merit pay system to give better performing teachers higher wages, and gave broader authority to school superintendents to terminate the employment of teachers and restricts the collective bargaining rights of teachers.[66]

WGU Indiana was established through an executive order on June 14, 2010 by Daniels, as a partnership between the state and Western Governors University in an effort to expand access to higher education for Indiana residents and increase the percentage of the state’s adult population with education beyond high school.

Curriculum and funding

In July 2013, the Associated Press obtained emails under Indiana open record laws in which Daniels asked for assurances that a textbook, "The People's History of the United States," written by historian Howard Zinn "is not in use anywhere in Indiana." Daniels wrote in 2010, "This crap should not be accepted for any credit by the state."[68][69][70][71][72] Daniels' e-mails were addressed to Scott Jenkins, his education adviser, and David Shane, a top fundraiser and state school board member. Daniels and his aides came to agreement and the governor wrote to them, “Go for it. Disqualify propaganda ...." Part of Shane's input was that a statewide review “would force to daylight a lot of excrement.”[70] Though Teresa Lubbers, the state commissioner of higher education, was mentioned in the e-mails regarding the statewide review of courses, she later said that she "was never asked to conduct the survey of courses described in the e-mail exchanges, and that her office did not conduct such a survey".[69]

In one of the emails, Daniels expressed contempt for Zinn upon his death:

This terrible anti-American academic has finally passed away...The obits and commentaries mentioned his book, ‘A People’s History of the United States,’ is the ‘textbook of choice in high schools and colleges around the country.’ It is a truly execrable, anti-factual piece of disinformation that misstates American history on every page. Can someone assure me that it is not in use anywhere in Indiana? If it is, how do we get rid of it before more young people are force-fed a totally false version of our history?[73]

Three years later, in the wake of the revelations, 90 of Purdue's roughly 1,800 professors issued an open letter expressing their concern over Daniels' commitment to academic freedom.[74][75] Daniels responded by saying that if Zinn were alive and a member of the Purdue faculty, he would defend his free speech rights and right to publish.[76] In a letter responding to the professors, Daniels wrote, "In truth, my emails infringed on no one's academic freedom and proposed absolutely no censorship of any person or viewpoint."[68]

In a separate and unrelated round of emails composed in 2009, Indiana Education officials shared concerns with Daniels about the lobbying resources and activities of the Indiana Urban Schools Association. Daniels asked that the administration "examine cutting them out, at least of the [funding] 'surge' we are planning for the next couple yrs." The executive director of IUSA is Charles Little, an Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis professor of education, who had criticized him. It wasn’t immediately clear if the audit went through.[68] Daniels said he had never heard of Charles Little.[77]

Abortion

On April 27, 2011, the Indiana legislature passed a bill authored by State Rep. Eric Turner that prohibited taxpayer dollars from supporting organizations that performed abortions. The legislation also prohibited abortions for women more than 20 weeks pregnant, four weeks sooner than the previous law.[78] Although Daniels would later say he supported the bill from the outset, it was not part of his legislative agenda and he did not indicate whether he would sign or veto the law until after it passed the General Assembly.[79] Daniels signed the bill on May 10, 2011.[78]

Planned Parenthood and the ACLU subsequently brought a lawsuit against the state alleging it was being targeted unfairly, that the state law violated federal medicaid laws, and that their Fourteenth Amendment rights were violated. A May 11 ruling allowing the case to move forward, but denied the request from the petitioners to grant a temporary injunction to restore the funding;[80] however, a June 24 ruling prohibited the state from enforcing the law.[81]

Daniels also signed at the end of the 2011 session a bill banning synthesized marijuana.[63]

Immigration

On May 10 Daniels signed into law two immigration bills; one denying in-state tuition prices to illegal immigrants and another creating fines for employers that employed illegal immigrants. Several protestors, at least five of whom were illegal immigrants, were arrested while protesting the law at the statehouse when they broke into Daniels' office after being denied a meeting. Student leaders called for their release, while some state legislators called for their deportation.[82]

State Democratic Party leaders accused Daniels and the Republicans of passing controversial legislation only to enhance Daniels image so he could seek the Presidency. Daniels, however, denied the charges saying he would have enacted the same agenda years earlier had the then-Democratic majority permitted him to do so.[63]

Budget cuts

The state forecast continued revenue declines in 2010 that would result in a $1.7 billion budget shortfall if the state budget grew at its normal rate. Daniels submitted a two-year $27.5 billion spending plan to the General Assembly which would result in a $500 million surplus that would be used to rebuild the state reserve funds to $1 billion. He proposed a wide range of budget austerity measures, including employee furloughing, spending reductions, freezing state hiring, freezing state employee wages, and a host of administrative changes for state agencies. The state had already been gradually reducing its workforce by similar freezes, and by 2011, Indiana had the fewest state employees per capita than any other state—a figure Daniels touted to say Indiana had the nation's smallest government.[83][84]

Daniels backed the creation of additional toll roads, expanding on his 2006 overhaul of the Indiana Toll Road system (known as "Major Moves"), in an attempt to secure an additional source of revenue for the state. But opposition from within his own party led to the bill being withdrawn by its Republican sponsor, Sen. Tom Wyss, which resulted in Daniels's only significant legislative defeat during the 2011 session.[67]

The legislative walkouts delayed progress on the budget passage for nearly two months, but the House of Representatives was able to begin working on it in committee in April. The body made several alterations to the bill, including a reapportionment of education funding based more heavily on the number of students at a school, and removing some public school funding to finance the new voucher system and charter schools.[84]

Energy

Daniels announced in October 2006 that a substitute natural gas company intended to build a facility in southern Indiana that would produce pipeline quality substitute natural gas (SNG).[85] The lead investor was Leucadia National, which proposed a $2.6 billion plant in Rockport, Indiana. Under the terms of the deal endorsed by Daniels, the state would buy almost all the Rockport gas and resell it on the open market throughout the country. If the plant made money from the sale, excess profits would be split between Leucadia National's Indiana subsidiary, Indiana Gassification, and the state. If it lost money from the sale, then 100% of the losses would be passed onto Indiana consumers. Leucadia agreed to reimburse the state for any losses, up to $150 million over 30 years.[86] Gas from the plant would make up about 17 percent of the state's supply. Critics feared that if gas prices fell over the next 30 years, the costs of the lost profits would get passed onto the bills of residents once the $150 million guarantee by Leucadia was used up.[86] The deal also received criticism due to government intrusion in the energy markets.[87] Questions were also raised due to Leucadia National hiring Mark Lubbers to promote the deal. Lubbers is a former aide and close friend of Daniels.[88] The Daniels administration maintained that the plant would create jobs in an economically depressed part of the state and offer environmental benefits through an in-state energy source.[28] The project was ultimately panned by the state legislature in 2013.[89]

Right to Work

Indiana became the first state in a decade to adopt Right to Work legislation.[90] Indiana is home to many manufacturing jobs. The Indiana Economic Development Corp. has reported that 90 firms said the new law was an important factor in deciding to move to Indiana.[91] Gov. Daniels signed the legislation on Feb 1, 2012 without much fanfare in the hopes of dispersing labor protesters before the Super Bowl in Indianapolis.[92]

2012 presidential speculation

Although Daniels had claimed to be reluctant to seek higher office, many media outlets, including Politico, The Weekly Standard, Forbes, The Washington Post, CNN, The Economist, and The Indianapolis Star began to speculate that Daniels may intend to seek the Republican nomination for president in 2012 after he joined the national debate on cap and trade legislation by penning a response in The Wall Street Journal to policies espoused by the Democratic-majority Congress and the White House in August 2010.[44][93] The speculation has included Daniels' record of reforming government, reducing taxes, balancing the budget, and connecting with voters in Indiana.[94][95][96][97] Despite his signing into law of bills that toughened drug enforcement, regulated abortion, and a defense of marriage act, he has angered some conservatives because of his call for a "truce" on social issues so the party can focus on fiscal issues. His "willingness to consider tax increases to rectify a budget deficit" has been another source of contention.[98]

In August 2010, The Economist praised Daniels' "reverence for restraint and efficacy" and concluded that "he is, in short, just the kind of man to relish fixing a broken state—or country."[44] Nick Gillespie of Reason called Daniels "a smart and effective leader who is a serious thinker about history, politics, and policy," and wrote that "Daniels, like former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson, is a Republican who knows how to govern and can do it well."[99] In February 2011, David Brooks of The New York Times described Daniels as the "Party's strongest [would be] candidate", predicting that he "couldn't match Obama in grace and elegance, but he could on substance."[100]

On December 12, 2010, Daniels suggested in a local interview that he would decide on a White House run before May 2011.[101]

Different groups and individuals pressured Daniels to run for office.[102] In response to early speculation, Daniels dismissed a presidential run in June 2009, saying "I've only ever run for or held one office. It's the last one I'm going to hold."[103] However, in February 2010 he told a Washington Post reporter that he was open to the idea of running in 2012.[104]

On March 6, 2011, Daniels was the winner of an Oregon (Republican Party) straw poll. Daniels drew 29.33% of the vote, besting second place finisher Mitt Romney (22.66%) and third place finisher Sarah Palin (18.22%), and was the winner of a similar straw poll in the state of Washington.[105] On May 5, 2011, Daniels told an interviewer that he would announce "within weeks" his decision of whether or not to run for the Republican presidential nomination. He said he felt he was not prepared to debate on all the national issues, like foreign policy, and needed time to better understand the issues and put together formal positions.[106] Later in May, as the Republican field began to resolve with announcements and withdrawals of other candidates, Time said, "Even setting aside his somewhat unusual family situation, Daniels would need to hurry to put together an organization" and raise enough money if he intended to run.[107]

Daniels announced he would not seek the Republican nomination for the presidency on the night of May 21, 2011, via an email to the press, citing family constraints and the loss of privacy the family would experience should he become a candidate.[108]

2016 presidential speculation

In January 2014, the Republican National Committee sent an email to subscribers, asking them to pick their top three presidential choices. The poll included thirty two potential candidates including Daniels.[109]

Purdue University

Selection

The Purdue University Board of Trustees unanimously elected Mitch Daniels president of Purdue University on June 21, 2012. As governor, Daniels had appointed 8 of the 10 Board members and had reappointed the other two, which critics claimed was a conflict of interest. A state investigation released in October 2012 found that the circumstances did not violate the Indiana Code of Ethics.[110] Other critics of his selection pointed out that unlike previous Purdue presidents, he lacked a background in academia.[111] His term as president began upon completion of his term as governor in January 2013. In preparation for his term as President of Purdue University, Daniels stopped participating in partisan political activity during the 2012 election cycle and focused instead on issues related to higher education and fiscal matters.

In order to avoid the financial cost of a formal inauguration, Daniels instead wrote an "Open Letter to the People of Purdue" in which he documented the challenges facing higher education and outlined his initial priorities such as affordability, academic excellence and academic freedom.[112] Daniels has continued this practice, opting to send Open Letters to the Purdue community instead of giving a formal State of the University speech, as is more common in higher education.

Student interactions

Daniels works out daily at the student gym and eats frequently with students in student dining facilities.[113] In March 2013, he joined forces with a group of engineering students to create a viral music video promoting engineering and Purdue University. Within 24 hours, the video had received over 50,000 views.[114]

Purdue home football games feature a segment entitled "Where's Mitch?", in which, the stadium video board shows the camera panning the crowd and eventually finding Daniels sitting among the fans, sometimes in the student section. Former Purdue President's rarely left their suite in the press-box structure.

Tuition freezes and cost reductions

The total cost of attending Purdue has fallen since Daniels assumed Purdue’s presidency, despite a trend at Big Ten institutions of rising costs. Total loan debt among the student body has also fallen 18% or $40 million.[115] Tuition at Purdue, prior to Daniels’ arrival had increased every year since 1976.[116] Two months after Daniels assumed his role as president, Purdue announced it would freeze tuition for two years, later extending the freeze for a third year. Because of the consecutive freezes, four-year graduates from the class of 2016 will become the first in at least 40 years to leave Purdue having never experienced a tuition increase.[117]

Daniels committed to freezing tuition before the state had determined Purdue's funding for the next biennium. Amidst questions about the timing, Daniels argued that he didn't need to wait because "it doesn't matter what the General Assembly does. This is the right thing to do and we are going to do it...the same way families do; the same way some governments do and all businesses do. We are going to adjust our spending to what we believe is the available and in this case the fair amount of revenue. I know often with good reason there has been an opportunity in higher education to adjust tuition to match what the place wanted to spend, and I just think we've reached the point where we ought to break that pattern."[118] The first tuition freeze required the university to find $40 million in savings or new revenue. In order to make up for the lost revenue from the tuition freeze, the Purdue Board of Trustees reduced the budgets of the Calumet and Fort Wayne satellite campuses, among other cuts. [119] Thanks in part to increased state funding, the university was able to still allocate an estimated $25 million to expand the school's engineering department.[120]

Daniels also reduced meal plan rates by 10 percent and cut the university's cooperative education fees which had increased every year prior on record. The meal cost reduction and fee cut affected 10,000 students and saved them and their families $3.5 million.[121] In fall 2014, Daniels announced a deal with Amazon to save students on textbooks and provide students, faculty and staff with free one day shipping to locations on campus.[122]

Agenda

In September 2013, Daniels announced the major priorities of his administration, known as "Purdue Moves."[123] The plan continued Daniels’ focus on affordability but also called for new investments in research, and STEM, including an addition of 165 new faculty. In an open letter to the Purdue community in January of 2014, Daniels announced that he would award $500,000 to the first academic unit that developed a 3-year degree program and another $500,000 to the first to develop a competency based degree program.[124]

Compensation

When Daniels was hired by Purdue he requested that is salary be less than his predecessors maximum salary and that 30 percent of his take home be based on the results of biannual performance reviews. Daniel’s base salary of $420,000 is $135,000 less than the prior president’s salary. Under the contract, his salary can grow to a maximum of $546,000 based on the results of a performance-bonus system—still less than his predecessor and the 3rd lowest in the 12-member Big Ten.[125] In November 2014, Daniels earned 88 percent of his at risk pay, receiving the grade of a B+ from the Trustees.[126]

Board service

In February 2013, Daniels was asked to co-chair a National Research Council committee to review and make recommendations on the future of the U.S. human spaceflight program. Daniels also co-chairs a Council on Foreign Relations Task Force on NonCommunicable diseases.[127] In March 2013, Daniels was elected to the board of Energy Systems Network (ESN), Indiana’s industry-driven clean technology initiative.

Electoral history

| Indiana gubernatorial election, 2004 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

| Republican | Mitch Daniels | 1,302,912 | 53.2 | ||

| Democratic | Joe Kernan (Incumbent) | 1,113,900 | 45.5 | ||

| Libertarian | Kenn Gividen | 31,664 | 1.3 | ||

| Indiana gubernatorial election, 2008 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

| Republican | Mitch Daniels (Incumbent) | 1,542,371 | 57.8 | ||

| Democratic | Jill Long Thompson | 1,067,863 | 40.1 | ||

| Libertarian | Andy Horning | 56,651 | 2.1 | ||

Authorship

- Daniels, Mitch (2012), Aiming Higher: Words That Changed a State, IBJ Book Publishing, ISBN 978-1-934922-86-6

- Daniels, Mitch (2011), Keeping the Republic: Saving America by Trusting Americans, Sentinel, ISBN 978-1-59523-080-5

- Daniels, Mitch (2004), Notes from the Road: 16 months of towns, tales and tenderloins, Mitch Daniels Transition Team, ISBN 978-0-9766026-0-6

See also

References

- ↑ Vaughan, Martin A. (June 11, 2008). "States Move To Cut, Cap Property Taxes As Home Values Decline, Many Will Have to Make Up Lost Revenue by Other Means". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Leonhardt, David (January 4, 2011). "Budget Hawk Eyes Deficit". nytimes.com.

- ↑ Davey, Monica (February 1, 2012). "Indiana Governor Signs a Law Creating a ‘Right to Work’ State". nytimes.com.

- ↑ York, Byron (June 4, 2009). "Can Mitch Daniels save the GOP?". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- ↑ Will, George F. (2010-02-07). "Charting a simple road to government solvency". Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ Douthat, Ross (2010-03-01). "A Republican Surprise". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ King, Neil (2011-05-22). "Daniels Withdraws From Presidential Race". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-05-22.odyssey=tab%7Cmostpopular%7Ctext%7CFRONTPAGE

- ↑ "Governor Fun Facts". State of Indiana. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ↑ "Gov. Daniels says White House speculation reinforced Syrian roots". Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 "Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels". National Governors Association. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Gugin, p. 404

- ↑ "2009 Kahlil Gibran Gala". Arab American Institute. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- ↑ "Ancestry of Mitch Daniels". Wargs.com. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ At Statesmen's Dinner, Republicans urged to flip Obama's slogan on its head

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Indianapolis Monthly 25. April 2002. pp. 142–45. ISSN 0899-0328.

- ↑ "Presidential Scholars". Presidential Scholars Association. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Schleifer, Teddy (February 24, 2011). "Daniels ’71: Into the spotlight". The Daily Princetonian. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- ↑ "Democrats want more info on Daniels' arrest". Wthr.com. 1970-05-14. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ Sullum, Jacob (2011-03-02) Mitch Daniels' Pot Luck, Reason

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "Mitch Daniels". IndyStar. 01-11-2005. Retrieved 2008-07-09. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Daniels, Mitch, The Washington Post, August 22, 1989, accessed May 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Public-Relations Pair to Join Lugar Staff." Indianapolis Star, 07 December, 1974, p. 26: "Daniels, 25, a CCI vice-president who worked in Lugar's office as a summer interne [sic] in 1969 and 1970…"

- ↑ "About the Governor: Mitchell E. Daniels, Jr., Governor of Indiana". in.gov. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ "Twenty Largest Indiana Public Companies" (PDF). Indiana State Auditor. 1998. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ferguson, Andrew (2010-06-14). "Ride Along With Mitch". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ↑ "The Eli Lilly Years". gooznewsauthor=Kensen, Joanne. May 11, 2011. Retrieved 2012-05-12.

- ↑ Slevin, Peter (2004-10-04). "In Indiana Race, Bush's Budget Blade Becomes 'My Man Mitch'". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

President Bush admiringly called him "the Blade," for the gleam in his budget-cutting eye.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Daniels, Mitchell E. , Jr., "Remarks to The National Press Club", whitehouse.gov, 11/28/2001.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Ross Douthat's Blog, 3 March 2010". The New York Times. 2010-03-03. Retrieved 2011-03-10.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Douthat, Ross (2010-03-01). "A Republican Surprise". New York Times.

- ↑ nytimes.com, 2002/12/31.

- ↑ cnn.com, 2003/01/01.

- ↑ Bush to Seek $75 Billion to Fight War, Terrorism, March 25, 2003, Los Angeles Times. The total request was for $75 billion but only $53 billion went to Iraq operations. "The spending measure would cover these expenses to the end of this fiscal year—Sept. 30—according to a senior administration official who briefed reporters Monday."

- ↑ CBO Congressional Testimony, October 24, 2007, Table 2, Pg. 4, in the 2003 column

- ↑ CBO Appropriations for Iraq and Afghanistan

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 Gugin, p. 402

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Gugin, p. 403

- ↑ Stoll, Ira (2010-03-08). "Mitch Daniels on the State of the Nation". Hudson Institute. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ↑ "Wisconsins Unions Get Ugly". Wall Street Journal. April 1, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "State Releases Budget Numbers". Inside Indiana Business. July 15, 2005. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Hemmingway, Mark (2009). "Mitch the Knife". National Review. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Gugin, p. 405

- ↑ Mwape, James Muma (2009). Guide to Electronic Toll Payments. Xulon Press. ISBN 978-1-61579-364-8.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Mitch Daniels: The right stuff". The Economist. 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ Gugin, p. 206

- ↑ "Governor visits Indiana troops in South Korea". Indystar.com. 25 June 2006.

- ↑ Barnes, Fred (Sep. 15, 2007). "Hoosier Jump Shot". The Wall Street Journal. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Health Indiana Plan". HealthyIndianaPlan.org. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- ↑ Lederman, Doug (2010-07-14). "Indiana teams up with WGU to educate adults online". USA Today.

- ↑ insideindianabusiness.com.

- ↑ "Governor Signs Property Tax Relief Bill" (PDF). IN.gov. 2010-03-19. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ↑ "Indiana Voters OK property tax cap". Indianapolis Business Journal. Associated Press. November 2, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ↑ Goodman, Josh (2008). "Public Officials of the Year". Governing magazine. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ "2008 Urban Innovator Award Winner". Manhattan Institute. 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Barns, Robert (April 29, 2008). "High Court Upholds Indiana Voter Registration Law". Washington Post. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ↑ "Governor Mitch Daniels Well-Positioned Entering Election Year". Republican Governors' Association. 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ↑ "Indiana – Election Results 2008 – The New York Times". Elections.nytimes.com. 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ Cillizza, Chris. "The Best Gubernatorial Campaign of 2008". Voices.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ↑ Van Wyk, Rich. "Dallara picked for new IndyCar chassis". WTHR-TV. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ "Dallara commits to new Speedway facility". IndyCar Series. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- ↑ "Award Recipients". Fiscy. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ Trinko, Katrina (November 18, 2010). "Mitch Daniels’s Next Hurdle". National Review. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 Weidenbener, Lesley (May 1, 2011). "title unknown". Louisville Courier-Journal. pp. A1, A18.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Democratic lawmakers leave Indiana, block labor bill". Indianapolis Business Journal. Associated Press. February 22, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ↑ "State Budgets and Public Unions", transcript, The Diane Rehm Show, 2011-02-21. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Allen, Kevin (April 22, 2011). "Indiana OKs Voucher program". South Bend Tribune. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Shella, Jim (April 25, 2011). "DANIEls Chalks Up Legislative Wins". WISHTV News. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 "Read Mitch Daniels emails about Howard Zinn", Journal & Courier, July 17, 2013.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Jaschik, Scott, "The Governor's Bad List", Inside Higher Ed, July 17, 2013.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "As governor, Mitch Daniels looked to censor academic writings and courses", Indystar.com, Jul. 16, 2013.

- ↑ Rothschild, Matthew, "How Mitch Daniels Had It In for Howard Zinn", progressive.org, July 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Censoring Howard Zinn: Former Indiana Gov. Tried to Remove 'A People’s History' from State Schools", DemocracyNow!, July 22, 2013. Including interviews with Anthony Arnove, co-editor with Zinn of "Voices of a People’s History of the United States," and Cornel West, professor at Union Theological Seminary and, formerly, at Princeton and Harvard. Retrieved 2013-07-22.

- ↑ Ohlheiser, Abby. "Former Governor, Now Purdue President, Wanted Howard Zinn Banned in Schools". Atlantic Wire. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Wang, Stephanie. "Purdue faculty 'troubled' by Mitch Daniels' Howard Zinn comments". Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ LoBianco, Tom (2013-07-22). "Mitch Daniels Letter: Purdue Professors Blast Former GOP Gov Over Howard Zinn Comments". Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Krull, John. "Daniels says issue is not freedom but Zinn's scholarship". Evansville Courier & Press. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Kehoe, Troy, "Daniels says report 'distorted' emails", WISH-TV.com, July 17, 2013. "The former governor said he had never heard of Charles Little prior to this week..."

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 House Bill 1210, Indiana General Assembly 2011 Session.

- ↑ Indiana Gov. Daniels to Sign Bill Defunding Planned Parenthood, April 29, 2011

- ↑ Gillers, Heather (May 11, 2011). "Planned Parenthood eyes restraining order". USA Today. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- ↑ Guyett, Susan (2011-06-25). "Indiana can't end Planned Parenthood funds: judge". Reuters. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ↑ Nye, Charlie (May 11, 2011). "Immigration bills signed amid arrests". IndyStar.com. Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- ↑ "Ways and Means Presentation" (PDF). Governor's Office. March 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-014. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 84.0 84.1 Carden, Dan (2011-04-28). "State budget set for final vote : Elections". Nwitimes.com. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ↑ Indiana advances leadership in clean coal technology., Indiana Governor History, March 24, 2009.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Evanoff, Ted (January 2, 2011). "Daniels takes natural gas bet that others refused". Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ↑ Bradner, Eric (2010-12-16). "State, developers reach agreement on Rockport, Ind., gasification plant". Courier & Press. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ↑ Welsh, Gary (May 1, 2011). "Lubbers: Critics Of Coal Gasification Deal Are Sneaky And Evil". Advance Indiana. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ↑ Bradner, Eric (2013-04-27). "BRADNER: Rockport plant will never be". Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ↑ economist.com.

- ↑ ibj.com

- ↑ wbez.org.

- ↑ Daniels, Mitch (15 May 2009). "Indiana Says 'No Thanks' to Cap and Trade". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Zickar, Lou (18 May 2009). "The innovators of today's GOP".

- ↑ Robinson, Peter (15 May 2009). "The Future Of The GOP". Forbes.

- ↑ Cillizza, Chris (12 May 2009). "Can Mitch Daniels Save the GOP?". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Tully, Matthew (17 May 2009). "How do Daniels' moves add up?".

- ↑ Silver, Nate (2011-02-04) A Graphical Overview of the 2012 Republican Field, New York Times

- ↑ Gillespie, Nick (2011-01-05) NY Times Flips its Whig Over Gov. Mitch Daniels (R-Ind.), Reason

- ↑ Brooks, David (February 25, 2011). "Run Mitch, Run". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- ↑ ^ Mellinger, Mark (2010-12-16). "Daniels to decide on WH run before May", WANE.com. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- ↑ Various (2 January 2011). "Student Initiative to Draft Daniels".

- ↑ "Daniels Ends 2012 Speculation". RealClearPolitics.com. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ↑ Cook, Dave (February 23, 2010). "Mitch Daniels open to presidential run, despite '100 reasons' to pass". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ Mapes, Jeff (March 6, 2011). "Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels wins GOP presidential straw poll in Oregon". The Oregonian. Retrieved 03-7-2011. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Haberman, Maggie (May 5, 2011). "Mitch Daniels". Politico. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ Duffy, Michael, "Seven Days in May: How One Week Clarified the GOP Field, Time magazine, May 15, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ↑ Haberman, Maggie (May 22, 2011). "Mitch Daniels won't run in 2012". Politico. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ↑ Siddiqui, Sabrina (January 10, 2014). "Republican National Committee Polls Voters On 2016 Presidential Candidates". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Thomas, David O. (October 16, 2012). The Governor as Purdue University President (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2013-01-14.

- ↑ Russell, John; Sabalow, Ryan; Schneider, Mary Beth; Sikich, Chris (June 20, 2012). "Gov. Mitch Daniels pick called a coup for Purdue, but qualifications questioned". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 2013-01-14.

- ↑ Daniels, Mitch. "An Open Letter to the People of Purdue".

- ↑ Weddle, Eric (Jan 19, 2013). "Daniels begins Purdue term with 12-hour days, fact-finding tour". Journal & Courier. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ↑ Video on YouTube.

- ↑ Daniels, Mitch (January 2015). "An Open Letter to the People of Purdue". Purdue.edu.

- ↑ . Purdue University http://www.purdue.edu/president/images/1501-openletter/Slide5.jpg. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Trustees extend tuition freeze through 2015-16 academic year". Purdue.edu/newsroom.

- ↑ "Purdue President Mitch Daniels on Tuition Freeze Plan". Press Conference, quote is 35 seconds in. WBAA News. March 1, 2013.

- ↑ Colombo, Hayleigh (May 18, 2003). "Purdue near $40M target; less than 3 months after tuition freeze news". Journal & Courier.

- ↑ "Purdue trustees review fee cuts and budget plan". The Purdue Exponent. May 12, 2013.

One area of investment over the next biennium will help fund a dramatic expansion in engineering faculty, with an estimated $25 million recurring investment in faculty, staff and facilities by the end of the biennium. The primary goal is to hire about 30 new faculty per year over five years.

- ↑ Colombo, Hayleigh (May 22, 2013). "Silence golden in vote on Purdue tuition freeze". Journal & Courier.

Factoring in a 5 percent meal plan reduction and a more than 50 percent cut in Purdue’s co-op fee, Purdue estimates more than 10,000 students and families will save about $3.5 million total.

- ↑ "Purdue, Amazon to offer students savings on textbooks, provide first-ever on-campus pickup services". Purdue Newsroom. August 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Daniels provides additional details on Purdue campus initiatives". Purdue News. Sep. 9, 2013. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Daniels awards prize for competency-based degree to Purdue Polytechnic Institute". Purdue Newsroom. September 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Purdue trims president's pay, breaks new ground for executive compensation", Purdue News, December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Tyner, Brittany (November 5, 2014). "Daniels awarded $111K in at-risk pay". WLFI.com.

- ↑ "Independent Task Force on Noncommunicable Diseases". Council on Foreign Relations. February 2014.

- Gugin, Linda C. & St. Clair, James E, ed. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mitch Daniels. |

- Purdue University President Mitch Daniels Purdue University site

- Appearances on C-SPAN

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jacob Lew |

Director of the Office of Management and Budget 2001–2003 |

Succeeded by Joshua Bolten |

| Preceded by Joe Kernan |

Governor of Indiana 2005–2013 |

Succeeded by Mike Pence |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Timothy Sands Acting |

President of Purdue University 2013–present |

Incumbent |

| ||||||||

| ||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

|