Misia Sert

| Misia Sert | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Maria Zofia Olga Zenajda Godebska March 30, 1872 St. Petersburg, Russia |

| Died |

October 15, 1950 (aged 78) Paris, France |

| Occupation | pianist, patron of the arts |

Misia Sert (born Maria Zofia Olga Zenajda Godebska; March 30, 1872 – October 15, 1950) was a pianist of Polish descent who hosted an artistic salon in Paris. She was a patron and friend of numerous artists, for whom she regularly posed.

Early life

Maria Zofia Olga Zenajda Godebska was born on March 30, 1872 in Tsarskoye Selo, outside of St. Petersburg, Russia. Her father, Cyprian Godebski was a renowned Polish sculptor, and professor at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. Her mother, Zofia Servais, of Russian- Belgian extraction, was the daughter of noted Belgian cellist, Adrien-François Servais. Aware of her husband’s propensity to engage in extra-marital affairs, a concerned, pregnant Zofia traveled to Tsarskoye Selo, where she surprised Godebski who was living with his current mistress.[1] Zofia Godebska died after giving birth to her daughter, thereafter called Misia, the Polish diminutive of the name Maria.

The infant was sent to live with her maternal Servais grandparents in Brussels. It was a musical household which hosted concerts performed by noted musicians. Franz Liszt was a friend of the family. It was in this environment that Sert received her musical education, her grandfather introducing the child barely out of infancy, to musical notes.[1] Under his mentorship, she became a gifted pianist.

Sert's father remarried several times, ultimately reclaiming his daughter and bringing her to live with him and her newest stepmother in Paris. Sert missed the ambiance of her grandparents’ home in Brussels. Her father placed her in a convent boarding school, the Sacre-Coeur. She remained there for six years, her only pleasure being the piano lessons she took one day a week as the student of the eminent Gabriel Fauré. At age fifteen, an argument with her stepmother caused Sert to flee home for London on money she had managed to borrow. After several months she returned to Paris, taking her own lodgings, supporting herself as a piano teacher to students referred to her by Fauré.[1]

Marriages and social milieu

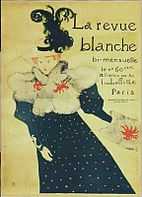

At age 21 Sert married her twenty-year-old cousin Thadée Natanson, a Polish émigré. Natanson dedicated most of his time frequenting the haunts favored by the artistic and intellectual circles of Paris. He became involved in political causes, championing the ideals of socialism, which he shared with his friend Leon Blum, and was a Dreyfusard. The Natanson home on the Rue St. Florentine became a gathering place, a salon, for such cultural lights as Marcel Proust, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Odilon Redon, Paul Signac, Claude Debussy, Stéphane Mallarmé, and André Gide. The entertainment was lavish. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec enjoyed playing bartender at parties the Natanson's hosted and became known for serving a potent cocktail— a drink of colorful layered liqueurs dubbed the Pousse-Café.[2] All were mesmerized by the charm and youth of their hostess. In 1889, Natanson debuted, La Revue blanche, a periodical committed to the discovery and nurture of new talent and to serve as a showcase for the work of the post-Impressionists, Les Nabis. Sert became the muse and symbol of La Revue blanche, appearing in advertising posters created by Toulouse-Lautrec, Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard.[3] A portrait of Sert by Renoir is now in the Tate Gallery. Marcel Proust used Sert as the prototype for the characters of "Princess Yourbeletieff" and "Madame Verdurin" in his roman à clef, the epic work, "À la recherche du temps perdu," ("Rembrance of Things Past").[2]

Natanson’s La Revue blanche coupled with his political activism required an influx of capital, which he alone was unable to supply. Needing a benefactor, he connected with Alfred Edwards, a newspaper magnate, the founder of the foremost newspaper in Paris, Le Matin. Edwards had become enamored with Sert and had taken her as his mistress in 1903. He would supply money, but only on the condition that Natanson relinquish his wife to him.

On February 24, 1905, Sert became the wife of Alfred Edwards. Sert and her new husband took up an opulent lifestyle in their apartment on Rue de Rivoli, overlooking the Tuileries. Here Sert continued welcoming artists, writers, and musicians in her home. Maurice Ravel dedicated Le Cygne (The Swan) in "Histoires naturelles" and La Valse (The Waltz) to her. Sert accompanied Enrico Caruso on the piano while the opera star entertained the assembled listeners with a repertory of Neapolitan songs.[4] Edwards proved an unfaithful husband, and he and Sert divorced in 1909.[5]

In 1914, Sert married her third husband, Spanish painter José-Maria Sert, (Josep Maria Sert). This period began her reign and fame as cultural arbiter, which lasted some fifty years. Writer Paul Morand described her as a "collector of geniuses, all of them in love with her." [6] It was recognized that "You had to be gifted before Misia wanted to know you." It was in her salon, while listening to Erik Satie at the piano playing his iconic composition "Trois Morceau en forme en poire" — that the assembled guests were informed that World War I had begun.[7]

The Sert marriage was an emotionally tumultuous one. Her husband became involved with a member of the aristocratic Russian Mdivani family, Princess Isabelle Roussadana Mdivani, known as “Roussy.” Sert tried to accommodate herself to the liaison her husband was having with another women. She herself also entered into a physical relationship with Rousssy. For some period of time the three—husband, wife, and Roussy—sustained a ménage á trois.[8]

The Sert’s social set was made up of bohemian elites, and the upper echelons of society. It was a libertine group rife with emotional, and sexual intrigues—all fueled by drug use and abuse.[9] She had an enduring association with couturiere Coco Chanel. The two met at the home of actress, Cécile Sorel in 1917, and thereafter were close friends. Sert provided Chanel with the emotional support the bereaved woman needed following the death of her lover, Arthur Capel in a car accident in 1918. It is said that theirs was an immediate bond of like souls, and Sert was attracted to Chanel by “her genius, lethal wit, sarcasm and maniacal destructiveness, which intrigued and appalled everyone.” Both women, convent bred, maintained a friendship of shared interests, confidences and drug use.[7][10][11]

Sert was generous and supportive to friends in need. She provided financial assistance to poet Pierre Reverdy when he needed funds to retreat to a Benedictine monastery in Solesmes. She also had a long association with Sergi Diaghilev and was involved in all creative aspects of the Ballets Russes from friendships with its dancers, to input on costume designs to choreography. Through the years she supplied funds for the often financially distressed ballet company. On the opening night of "Petrushka", she came to the rescue with the 4000 francs needed to prevent repossession of the costumes. When Diaghilev lay dying in Venice she was at his side and, after his death in August 1929, she paid for his funeral, honoring the man who had been such an important influence in the world of ballet.[2][12]

She weathered the World War II Nazi occupation of Paris without serious condemnation of her character, unlike some of her social set whose wartime activities and allegiances were questionable if not damning.[2]

Death

Misia Sert died on October 15, 1950 in Paris.

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Charles-Roux, Edmonde, "Chanel and her World," Hachette-Vendome, 1981, p. 143

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 http://www.clivejames.com, "Misia and All Paris," London Review of Books, 1980, retrieved August 10, 2012

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde, "Chanel and her World," Hachette-Vendome, 1981, p. 143, 145, 149

- ↑ .clivejames.com, "Misia and All Paris," London Review of Books, 1980, retrieved August 10, 2012

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde, "Chanel and her World," Hachette-Vendome, 1981, p. 149, 150, 152

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde, "Chanel and her World," Hachette-Vendome, 1981, p. 157

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 http://www.clivejames.com, "Misia and All Paris," London Review of Books, 1980, retrieved August 9, 2012

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde, "Chanel and her World," Hachette-Vendome, 1981, p. 234

- ↑ Vaughan, Hal, "Sleeping With the Enemy, Coco Chanel's Secret War," Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, p. 63

- ↑ Vaughan, Hal, "Sleeping With the Enemy, Coco Chanel's Secret War," Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, p. 13, 80-81

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde, "Chanel and her World," Hachette-Vendome, 1981, p. 158

- ↑ Charles-Roux, Edmonde, "Chanel and her World," Hachette-Vendome, 1981, p. 154, 234, 252

- Time Magazine Profile of Misia Sert

- A Biography for People who influenced Ravel

- A web page about well known salons, in French

- Gold, Arthur; Fizdale, Robert (1992). The Life of Misia Sert. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-74186-0.

- H.H. Stuckenschmidt - "Maurice Ravel" Variationen über Person und Werk

External links

- Pierre Bonnard, the Graphic Art, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Sert (see index)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portraits of Misia Sert. |

|