Minimum total potential energy principle

The minimum total potential energy principle is a fundamental concept used in physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering. It asserts that a structure or body shall deform or displace to a position that minimizes the total potential energy, with the lost potential energy being dissipated as heat. For example, a marble placed in a bowl will move to the bottom and rest there, and similarly, a tree branch laden with snow will bend to a lower position. The lower position is the position for minimum potential energy: it is the stable configuration for equilibrium. The principle has many applications in structural analysis and solid mechanics.

A binding energy is the energy that must be exported from a system for the system to enter a bound state at a negative level of energy. Negative energy is called "potential energy".[1] A bound system has a lower (i.e., more negative) potential energy than the sum of its parts—this is what keeps the system aggregated in accordance with the minimum total potential energy principle. Therefore, a system's binding energy is the system's synergy. This, in its turn, implies that the minimum total potential energy principle is the maximum total synergy principle.

Some examples

- A free proton and free electron will tend to combine to form the lowest energy state (the ground state) of a hydrogen atom, the most stable configuration. This is because that state's energy is 13.6 electron volts (eV) lower than when the two particles separated by an infinite distance. The dissipation in this system takes the form of spontaneous emission of electromagnetic radiation, which increases the entropy of the surroundings.

- A rolling ball will end up stationary at the bottom of a hill, the point of minimum potential energy. The reason is that as it rolls downward under the influence of gravity, friction produced by its motion transfers energy in the form of heat of the surroundings with an attendant increase in entropy.

- A protein folds into the state of lowest potential energy. In this case, the dissipation takes the form of vibration of atoms within or adjacent to the protein.

Structural Mechanics

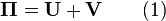

The total potential energy,  , is the sum of the elastic strain energy, U, stored in the deformed body and the potential energy, V, associated to the applied forces:

, is the sum of the elastic strain energy, U, stored in the deformed body and the potential energy, V, associated to the applied forces:

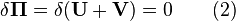

This energy is at a stationary position when an infinitesimal variation from such position involves no change in energy:

The principle of minimum total potential energy may be derived as a special case of the virtual work principle for elastic systems subject to conservative forces.

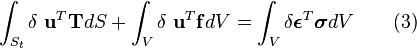

The equality between external and internal virtual work (due to virtual displacements) is:

where

-

= vector of displacements

= vector of displacements -

= vector of distributed forces acting on the part

= vector of distributed forces acting on the part  of the surface

of the surface -

= vector of body forces

= vector of body forces

In the special case of elastic bodies, the right-hand-side of (3) can be taken to be the change,  , of elastic strain energy U due to infinitesimal variations of real displacements.

In addition, when the external forces are conservative forces, the left-hand-side of (3) can be seen as the change in the potential energy function V of the forces. The function V is defined as:

, of elastic strain energy U due to infinitesimal variations of real displacements.

In addition, when the external forces are conservative forces, the left-hand-side of (3) can be seen as the change in the potential energy function V of the forces. The function V is defined as:

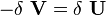

where the minus sign implies a loss of potential energy as the force is displaced in its direction. With these two subsidiary conditions, (3) becomes:

This leads to (2) as desired. The variational form of (2) is often used as the basis for developing the finite element method in structural mechanics.

References

- ↑ Why is the Potential Energy Negative? HyperPhysics