Mineral physics

Mineral physics is the science of materials that compose the interior of planets, particularly the Earth. It overlaps with petrophysics, which focuses on whole-rock properties. It provides information that allows interpretation of surface measurements of seismic waves, gravity anomalies, geomagnetic fields and electromagnetic fields in terms of properties in the deep interior of the Earth. This information can be used to provide insights into plate tectonics, mantle convection, the geodynamo and related phenomena.

Laboratory work in mineral physics require high pressure measurements. The most common tool is a diamond anvil cell, which uses diamonds to put a small sample under pressure that can approach the conditions in the Earth's interior.

Creating high pressures

Achieving temperatures found within the interior of the earth is just as important to the study of Mineral Physics as creating high pressures. Several methods are used to reach these temperatures and measure them. Resistive heating is the most common and simplest to measure. The application of a voltage to a wire heats the wire and surrounding area. A large variety of heater designs are available including those that head the entire diamond anvil cell (DAC) body and those that fit inside the body to heat the sample chamber. Temperature below 700°C can be reached in air due to the oxidation of diamond above this temperature. With an argon atmosphere, higher temperatures up to 1700°C can be reached without damaging the diamonds. Resistive heaters have not achieved temperatures above 1000°C.

Laser-Heating is done in a diamond-anvil cell with Nd:YAG or CO2 lasers to achieve temperatures above 6000k. Spectroscopy is used to measure black body radiation from the sample to determine the temperature. Laser-heating is continuing to extend the temperature range that can be reached in diamond-anvil cell but suffers two significant drawbacks. First, temperatures below 1200°C are difficult to measure using this method. Second, large temperature gradients exist in the sample because only the portion of sample hit by the laser is heated.

Shock compression

Many of the pioneering studies in mineral physics involved explosions or projectiles that subjected a sample to a shock. For a brief time interval, the sample is under pressure as the shock wave passes through. Pressures as high as any in the Earth have been achieved by this method. However, the method has some disadvantages. The pressure is very non-uniform and is not adiabatic, so the pressure wave heats the sample up in passing. The conditions of the experiment must be interpreted in terms of a set of pressure-density curves called the Hugoniot curves.[1]

Multi-anvil press

Multi-anvil presses involve an arrangement of anvils to concentrate pressure from a press onto a sample. Typically the apparatus uses an arrangement eight cube-shaped tungsten carbide anvils to compress a ceramic octahedron containing the sample and a ceramic or Re metal furnace. The anvils are typically placed in a large hydraulic press. The method was developed by Kawai and Endo in Japan.[2] Unlike shock compression, the pressure exerted is steady, and the sample can be heated using a furnace. Pressures of about 28 GPa (equivalent to depths of 840 km),[3] and temperatures above 2300 °C,[4] can be attained using WC anvils and a lanthanum chromite furnace. The apparatus is very bulky and cannot achieve pressures like those in the diamond anvil cell (below), but it can handle much larger samples that can be quenched and examined after the experiment.[5] Recently, sintered diamond anvils have been developed for this type of press that can reach pressures of 90 GPa (2700 km depth).[6]

Diamond anvil cell

The diamond anvil cell is a small table-top device for concentrating pressure. It can compress a small (sub-millimeter sized) piece of material to extreme pressures, which can exceed 3,000,000 atmospheres (300 gigapascals).[7] This is beyond the pressures at the center of the Earth. The concentration of pressure at the tip of the diamonds is possible because of their hardness, while their transparency and high thermal conductivity allow a variety of probes can be used to examine the state of the sample. The sample can be heated to thousands of degrees.

Creating High Temperatures

Achieve temperatures found within the interior of the earth is just as important to the study of Mineral Physics as creating to desired pressures. Several methods are used to reach these temperatures and measure them. Resistive heating is the most common and easiest to measure. The application of a voltage to a wire heats the wire and surrounding area. A large variety of heater designs are available including those that head the entire DAC body and those that fit inside the body to heat the sample chamber. Temperature below 700 °C can be reached in air due to the oxidation of diamond above this temperature. With an argon atmosphere, higher temperatures up to 1700 °C can be reached without damaging the diamonds. Resistive heaters have not achieved temperatures above 1000 °C. Laser-Heating is done in a diamond-anvil cell with Nd:YAG or CO2 lasers to achieve temperatures above 6000k. Optical spectroscopy is used to measure black body radiation from the sample to determine the temperature. Laser-heating is continuing to extend the temperature range that can be reached in diamond-anvil cell but suffers to significant drawbacks. First, temperatures below 1200k are difficult to measure using this method. Second, large temperature gradients exist in the sample because only the portion of sample hit by the laser are heated.

Properties of materials

Equations of state

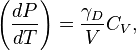

To deduce the properties of minerals in the deep Earth, it is necessary to know how their density varies with pressure and temperature. Such a relation is called an equation of state (EOS). A simple example of an EOS that is predicted by the Debye model for harmonic lattice vibrations is the Mie-Grünheisen equation of state:

where  is the heat capacity and

is the heat capacity and  is the Debye gamma. The latter is one of many Grünheisen parameters that play an important role in high-pressure physics. A more realistic EOS is the Birch–Murnaghan equation of state.[8]

is the Debye gamma. The latter is one of many Grünheisen parameters that play an important role in high-pressure physics. A more realistic EOS is the Birch–Murnaghan equation of state.[8]

Interpreting seismic velocities

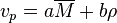

Inversion of seismic data give profiles of seismic velocity as a function of depth. These must still be interpreted in terms of the properties of the minerals. A very useful heuristic was discovered by Francis Birch: plotting data for a large number of rocks, he found a linear relation of the compressional wave velocity  of rocks and minerals of a constant average atomic weight

of rocks and minerals of a constant average atomic weight  with density

with density  :[9][10]

:[9][10]

.

.

This relationship became known as Birch's law. This makes it possible to extrapolate known velocities for minerals at the surface to predict velocities deeper in the Earth.

Other physical properties

- Viscosity

- Creep (deformation)

- Melting

- Electrical conduction and other transport properties

Methods of Crystal Interrogation

There are a number of experimental procedures designed to extract information from both single and powdered crystals. Some techniques can be used in a diamond anvil cell(DAC) or a multi anvil press(MAP). Some techniques are summarized in the following table.

| Technique | Anvil Type | Sample Type | Information Extracted | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction(XRD) | DAC or MAP | Powder or Single Crystal | cell parameters | |

| Electron Microscopoy | Neither | Powder or Single Crystal | Symmetry Group | Surface Measurements Only |

| Neutron Diffraction | Neither | Powder | cell parameters | Large Sample needed |

| Infrared spectroscopy | DAC | Powder, Single Crystal or Solution | Chemical Composition | Not all materials are IR active |

| Raman Spectroscopy | DAC | Powder, Single Crystal or Solution | Chemical Composition | Not all materials are Raman active |

| Brillouin Scattering | DAC | Single Crystal | Elastic Moduli | Need optically thin sample |

| Ultrasonic Interferometry[11] | DAC or MAP | Single Crystal | Elastic Moduli |

First Principles Calculations

Using quantum mechanical numerical techniques, it is possible to achieve very accurate predictions of crystal's properties including structure, thermodynamic stability, elastic properties and transport properties. The limit of such calculations tends to be computing power, as computation run times of weeks or even months are not uncommon.

References

- ↑ Ahrens, T. J. (1980). "Dynamic compression of Earth materials". Science 207 (4435): 1035–1041. Bibcode:1980Sci...207.1035A. doi:10.1126/science.207.4435.1035.

- ↑ Kawai, Naoto (1970). "The generation of ultrahigh hydrostatic pressures by a split sphere apparatus". Review of Scientific Instruments 41 (8): 1178–1181. Bibcode:1970RScI...41.1178K. doi:10.1063/1.1684753.

- ↑ Kubo, Atsushi; Akaogi, Masaki (2000). "Post-garnet transitions in the system Mg4Si4O12–Mg3Al2Si3O12 up to 28 GPa: phase relations of garnet, ilmenite and perovskite". Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 121 (1-2): 85–102. Bibcode:2000PEPI..121...85K. doi:10.1016/S0031-9201(00)00162-X.

- ↑ Zhang, Jianzhong; Liebermann, Robert C.; Gasparik, Tibor; Herzberg, Claude T.; Fei, Yingwei (1993). "Melting and subsolidus relations of silica at 9 to 14 GPa". Journal of Geophysical Research 98 (B11): 19785–19793. Bibcode:1993JGR....9819785Z. doi:10.1029/93JB02218.

- ↑ "Studying the Earth's formation: The multi-anvil press at work". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ↑ Zhai, Shuangmeng; Ito, Eiji (2011). "Recent advances of high-pressure generation in a multianvil apparatus using sintered diamond anvils". Geoscience Frontiers 2 (1): 101–106. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2010.09.005.

- ↑ Hemley, Russell J.; Ashcroft, Neil W. (1998). "The Revealing Role of Pressure in the Condensed Matter Sciences". Physics Today 51 (8): 26. Bibcode:1998PhT....51h..26H. doi:10.1063/1.882374.

- ↑ Poirier 2000

- ↑ Birch, F. (1961). "The velocity of compressional waves in rocks to 10 kilobars. Part 2". Journal of Geophysical Research 66 (7): 2199–2224. Bibcode:1961JGR....66.2199B. doi:10.1029/JZ066i007p02199.

- ↑ Birch, F. (1961). "Composition of the Earth's mantle". Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 4: 295–311. Bibcode:1961GeoJI...4..295B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1961.tb06821.x.

- ↑ http://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/mineralogy/mineral_physics/ultrasonic.html

Further reading

- Poirier, Jean-Paul (2000). Introduction to the Physics of the Earth's Interior. Cambridge Topics in Mineral Physics & Chemistry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66313-X.

External links

- "Teaching Mineral Physics Across the Curriculum". On the cutting edge - professional development for geoscience faculty. Retrieved 21 May 2012.