Military budget of the United States

| Part of a series on Government |

| United States budget and debt topics |

|---|

|

|

Major dimensions |

|

Programs |

|

Contemporary issues

|

|

Terminology |

The military budget is the portion of the discretionary United States federal budget allocated to the Department of Defense, or more broadly, the portion of the budget that goes to any military-related expenditures. This military budget pays the salaries, training, and health care of uniformed and civilian personnel, maintains arms, equipment and facilities, funds operations, and develops and buys new equipment. The budget funds all branches of the U.S. military: the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and Coast Guard.

For the period 2010-14, SIPRI found that the United States was the world's biggest exporter of major arms, accounting for 31 percent of global shares, followed by Russia with 27 percent. The USA delivered weapons to at least 94 recipients. The United States was also the world's eighth largest importer of major military equipment for the same period. The main imports were 19 transport aircraft from Italy; and equipment produced in the US under licence–including 252 trainer aircraft of Swiss design, 223 light helicopters of German design and 10 maritime patrol aircraft of Spanish design.[1]

Budget for 2011

For the 2011 fiscal year, the president's base budget for the Department of Defense and spending on "overseas contingency operations" combine to bring the sum to $664.84 billion.[2][3]

When the budget was signed into law on 28 October 2009, the final size of the Department of Defense's budget was $680 billion, $16 billion more than President Obama had requested.[4] An additional $37 billion supplemental bill to support the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan was expected to pass in the spring of 2010, but has been delayed by the House of Representatives after passing the Senate.[5][6]

Emergency and supplemental spending

The recent invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were largely funded through supplementary spending bills outside the federal budget, which are not included in the military budget figures listed below.[7] Starting in the fiscal year 2010, however, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were categorized as "overseas contingency operations", and the budget is included in the federal budget.

By the end of 2008, the U.S. had spent approximately $900 billion in direct costs on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The government also incurred indirect costs, which include interests on additional debt and incremental costs, financed by the Veterans Administration, of caring for more than 33,000 wounded. Some experts estimate the indirect costs will eventually exceed the direct costs.[8] As of June 2011, the total cost of the wars was approximately $3.7 trillion.[9]

By title

The federally budgeted (see below) military expenditure of the United States Department of Defense for fiscal year 2013 are as follows. While data is provided from the 2015 budget, data for 2014 and 2015 is estimated, and thus data is shown for the last year for which definite data exists (2013).[10]

| Components | Funding | Change, 2012 to 2013 |

| Operations and maintenance | $258.277 billion | -9.9% |

| Military Personnel | $153.531 billion | -3.0% |

| Procurement | $97.757 billion | -17.4% |

| Research, Development, Testing & Evaluation | $63.347 billion | -12.1% |

| Military Construction | $8.069 billion | -29.0% |

| Family Housing | $1.483 billion | -12.2% |

| Other Miscellaneous Costs | $2.775 billion | -59.5% |

| Atomic energy defense activities | $17.424 billion | -4.8% |

| Defense-related activities | $7.433 billion | -3.8% |

| Total Spending | $610.096 billion | -10.5% |

By entity

| Entity | 2010 Budget request[11] | Percentage of Total | Notes |

| Army | $244.9 billion | 31.8% | |

| Navy | $149.9 billion | 23.4% | excluding Marine Corps |

| Marine Corps | $40.0 billion | 4% | Total Budget taken allotted from Department of Navy |

| Air Force | $170.6 billion | 22% | |

| Defense Intelligence | $80.1 billion[12] | 3.3% | Because of classified nature, budget is an estimate and may not be the actual figure |

| Defense Wide Joint Activities | $118.7 billion | 15.5% |

Programs spending more than $1.5 billion

The Department of Defense's FY 2011 $137.5 billion procurement and $77.2 billion RDT&E budget requests included several programs with more than $1.5 billion.

| Program | 2011 Budget request[13] | Change, 2010 to 2011 |

| F-35 Joint Strike Fighter | $11.4 billion | +2.1% |

| Ballistic Missile Defense (Aegis, THAAD, PAC-3) | $9.9 billion | +7.3% |

| Virginia class submarine | $5.4 billion | +28.0% |

| Brigade Combat Team Modernization | $3.2 billion | +21.8% |

| DDG 51 Burke-class Aegis Destroyer | $3.0 billion | +19.6% |

| P–8A Poseidon | $2.9 billion | −1.6% |

| V-22 Osprey | $2.8 billion | −6.5% |

| Carrier Replacement Program | $2.7 billion | +95.8% |

| F/A-18E/F Hornet | $2.0 billion | +17.4% |

| Predator and Reaper Unmanned Aerial System | $1.9 billion | +57.8% |

| Littoral combat ship | $1.8 billion | +12.5% |

| CVN Refueling and Complex Overhaul | $1.7 billion | −6.0% |

| Chemical Demilitarization | $1.6 billion | −7.0% |

| RQ-4 Global Hawk | $1.5 billion | +6.7% |

| Space-Based Infrared System | $1.5 billion | +54.4% |

Other military-related expenditures

This does not include many military-related items that are outside of the Defense Department budget, such as nuclear weapons research, maintenance, cleanup, and production, which is in the Department of Energy budget, Veterans Affairs, the Treasury Department's payments in pensions to military retirees and widows and their families, interest on debt incurred in past wars, or State Department financing of foreign arms sales and militarily-related development assistance. Neither does it include defense spending that is not military in nature, such as the Department of Homeland Security, counter-terrorism spending by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and intelligence-gathering spending by NASA.

Historical spending

The following is historical spending on defense from 1996-2015, spending for 2014-15 is estimated.[10] The Defense Budget is shown in billions of dollars and total budget in trillions of dollars. The percentage of the total U.S. budget spent on defense is indicated in the third row, and change in defense spending from the previous year in the final row.

| 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| Defense Budget (Billions) |

266 | 270 | 271 | 292 | 304 | 335 | 362 | 456 | 491 | 506 | 556 | 625 | 696 | 698 | 721 | 717 | 681 | 610 | 614 | 637 |

| Total Budget (Trillions) |

1.58 | 1.64 | 1.69 | 1.78 | 1.82 | 1.96 | 2.09 | 2.27 | 2.41 | 2.58 | 2.78 | 2.86 | 3.32 | 4.08 | 3.48 | 3.51 | 3.58 | 3.48 | 3.64 | 3.97 |

| Defense Budget % |

16.8 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 20.1 | 20.4 | 19.6 | 20.0 | 21.9 | 20.9 | 17.1 | 20.7 | 20.4 | 19.1 | 17.5 | 16.8 | 16.0 |

| Defense Spending Change |

-0.1 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 7.8 | 4.0 | 10.1 | 8.2 | 26.0 | 7.6 | 3.1 | 10.0 | 12.5 | 11.3 | 0.2 | 3.4 | -0.6 | -5.0 | -10.5 | 0.6 | 3.8 |

Audit of implementation of budget for 2010

The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) was unable to provide an audit opinion on the 2010 financial statements of the US Government because of 'widespread material internal control weaknesses, significant uncertainties, and other limitations'.[16] The GAO cited as the principal obstacle to its provision of an audit opinion 'serious financial management problems at the Department of Defense that made its financial statements unauditable'.[16]

In FY 2010, six out of thirty-three DoD reporting entities received unqualified audit opinions.[17]

Chief financial officer and Under Secretary of Defense Robert F. Hale acknowledged enterprise-wide problems with systems and processes,[18] while the DoD's Inspector General reported 'material internal control weaknesses ... that affect the safeguarding of assets, proper use of funds, and impair the prevention and identification of fraud, waste, and abuse'.[19] Further management discussion in the FY 2010 DoD Financial Report states 'it is not feasible to deploy a vast number of accountants to manually reconcile our books' and concludes that 'although the financial statements are not auditable for FY 2010, the Department's financial managers are meeting warfighter needs'.[20]

Audit of 2011 budget

Again in 2011, the GAO could not "render an opinion on the 2011 consolidated financial statements of the federal government", with a major obstacle again being "serious financial management problems at the Department of Defense (DOD) that made its financial statements unauditable".[21]

In December 2011, the GAO found that "neither the Navy nor the Marine Corps have implemented effective processes for reconciling their FBWT." According to the GAO, "An agency’s FBWT account is similar in concept to a corporate bank account. The difference is that instead of a cash balance, FBWT represents unexpended spending authority in appropriations." In addition, "As of April 2011, there were more than $22 billion unmatched disbursements and collections affecting more than 10,000 lines of accounting."[22]

Support service contractors

The role of support service contractors has increased since 2001 and in 2007 payments for contractor services exceeded investments in equipment for the armed forces for the first time.[23] In the 2010 budget, the support service contractors will be reduced from the current 39 percent of the workforce down to the pre-2001 level of 26 percent.[24] In a Pentagon review of January 2011, service contractors were found to be "increasingly unaffordable."[25]

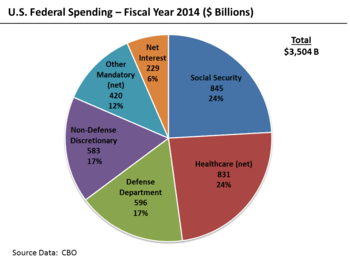

Military budget and total US federal spending

The U.S. Department of Defense budget accounted in fiscal year 2010 for about 19% of the United States federal budgeted expenditures and 28% of estimated tax revenues. Including non-DOD expenditures, military spending was approximately 28–38% of budgeted expenditures and 42–57% of estimated tax revenues. According to the Congressional Budget Office, defense spending grew 9% annually on average from fiscal year 2000–2009.[26]

Because of constitutional limitations, military funding is appropriated in a discretionary spending account. (Such accounts permit government planners to have more flexibility to change spending each year, as opposed to mandatory spending accounts that mandate spending on programs in accordance with the law, outside of the budgetary process.) In recent years, discretionary spending as a whole has amounted to about one-third of total federal outlays.[27] Department of Defense spending's share of discretionary spending was 50.5% in 2003, and has risen to between 53% and 54% in recent years.[28]

For FY 2010, Department of Defense spending amounts to 4.7% of GDP.[29] Because the U.S. GDP has risen over time, the military budget can rise in absolute terms while shrinking as a percentage of the GDP. For example, the Department of Defense budget is slated to be $664 billion in 2010 (including the cost of operations in Iraq and Afghanistan previously funded through supplementary budget legislation[30][31]), higher than at any other point in American history, but still 1.1–1.4% lower as a percentage of GDP than the amount spent on military during the peak of Cold-War military spending in the late 1980s.[29] Admiral Mike Mullen, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has called four percent an "absolute floor".[32] This calculation does not take into account some other military-related non-DOD spending, such as Veterans Affairs, Homeland Security, and interest paid on debt incurred in past wars, which has increased even as a percentage of the national GDP.

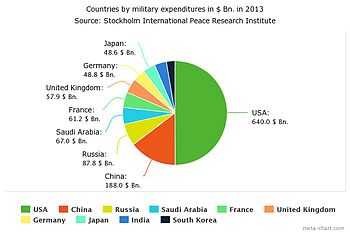

Comparison with other countries

The 2009 U.S. military budget accounts for approximately 40% of global arms spending. The 2012 budget is 6–7 times larger than the $106 billion military budget of China The United States and its close allies are responsible for two-thirds to three-quarters of the world's military spending (of which, in turn, the U.S. is responsible for the majority).[33][34][35] The US also maintains the largest number of military bases on foreign soil across the world.[36]

In 2005, the United States spent 4.06% of its GDP on its military (considering only basic Department of Defense budget spending), more than France's 2.6% and less than Saudi Arabia's 10%.[37]information 2006 This is historically low for the United States since it peaked in 1944 at 37.8% of GDP (it reached the lowest point of 3.0% in 1999–2001). Even during the peak of the Vietnam War the percentage reached a high of 9.4% in 1968.[38]

Recent commentary on military budget

Secretary of Defense Robert Gates wrote in 2009 that the U.S. should adjust its priorities and spending to address the changing nature of threats in the world: "What all these potential adversaries—from terrorist cells to rogue nations to rising powers—have in common is that they have learned that it is unwise to confront the United States directly on conventional military terms. The United States cannot take its current dominance for granted and needs to invest in the programs, platforms, and personnel that will ensure that dominance's persistence. But it is also important to keep some perspective. As much as the U.S. Navy has shrunk since the end of the Cold War, for example, in terms of tonnage, its battle fleet is still larger than the next 13 navies combined—and 11 of those 13 navies are U.S. allies or partners."[39] Secretary Gates announced some of his budget recommendations in April 2009.[40]

The Congressional Research Service has noted a discrepancy between a budget that is declining as a percentage of GDP while the responsibilities of the DoD have not decreased and additional pressures on the military budget have arisen due to broader missions in the post-9/11 world, dramatic increases in personnel and operating costs, and new requirements resulting from wartime lessons in the Iraq War and Operation Enduring Freedom.[41]

Four billion dollars of the five billion dollars in budget cuts mandated by the Congress in the 2013 budget were achieved by declaring that nearly 65 thousand troops were now temporary and no longer part of the permanent forces and so their costs were shifted to the Afghanistan war budget.[42]

As part of Obama's East Asia "pivot", his 2013 national military request moves funding from the Army and Marines to favor the Navy, but the Congress has resisted this.[43]

Reports emerged in February 2014 that Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel was planning to trim the defense budget by billions of dollars. The secretary in his first defense budget planned to limit pay rises, increase fees for healthcare benefits, freeze the pay of senior officers, and reduce military housing allowances. A reduction in the number of soldiers serving in the U.S. Army would reduce the size of the force to levels not seen since prior to the start of World War II.[44]

In July 2014, American Enterprise Institute scholar Michael Auslin opined in the National Review that the Air Force needs to be fully funded as a priority, due to the air superiority, global airlift, and long-range strike capabilities it provides.[45]

2012 fiscal cliff

On 5 December 2012, the Department of Defense announced it was planning for automatic spending cuts, which include $500 billion and an additional $487 billion due to the 2011 Budget Control Act, due to the fiscal cliff.[46][47][48][49][50] According to the newspaper Politico, the Department of Defense declined to explain to the House of Representatives Appropriations Committee, which controls federal spending, what its plans were regarding the fiscal cliff planning.[51]

This was after half a dozen defense experts either resigned from Congress or lost their reelection fights.[52]

Lawrence Korb has noted that given recent trends military entitlements and personnel costs will take up the entire defense budget by 2039.[53]

GAO audits

The Government Accountability Office was unable to provide an audit opinion on the 2010 financial statements of the U.S. government due to "widespread material internal control weaknesses, significant uncertainties, and other limitations."[54] The GAO cited as the principal obstacle to its provision of an audit opinion "serious financial management problems at the Department of Defense that made its financial statements unauditable."[16]

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2011, seven out of 33 DoD reporting entities received unqualified audit opinions.[55] Under Secretary of Defense Robert F. Hale acknowledged enterprise-wide weaknesses with controls and systems.[56] Further management discussion in the FY 2011 DoD Financial Report states "we are not able to deploy the vast numbers of accountants that would be required to reconcile our books manually".[55] Congress has established a deadline of FY 2017 for the DoD to achieve audit readiness.[57]

For FYs 1998-2010 the Department of Defense's financial statements were either unauditable or such that no audit opinion could be expressed .[58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69]

Reform

In a statement of 6 January 2011 Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates stated: "This department simply cannot risk continuing down the same path – where our investment priorities, bureaucratic habits and lax attitude towards costs are increasingly divorced from the real threats of today, the growing perils of tomorrow and the nation's grim financial outlook." Gates has proposed a budget which, if approved by the Congress, would reduce the costs of many DOD programs and policies, including reports, the IT infrastructure, fuel, weapon programs, DOD bureaucracies, and personnel.[70]

The 2015 expenditure for Army research, development and acquisition changed from $32 billion projected in 2012 for FY15, to $21 billion for FY15 expected in 2014.[71]

See also

| Wikinews has related news: Global annual military spending tops $1.2 trillion |

- United States military aid

- United States Foreign Military Financing

- Military budget of the Russian Federation

- Military budget of the People's Republic of China

- Foreign Military Sales

- Foreign policy of the United States

- Overseas expansion of the United States

- Overseas interventions of the United States

- List of United States military history events

- List of United States military bases

- List of countries by military expenditures

- List of countries by size of armed forces

- Top 100 US Federal Contractors

References

- ↑ "Trends in International Arms Transfer, 2014". www.sipri.org. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Updated Summary Tables, Budget of the United States Government Fiscal Year 2010 (Table S.12)

- ↑ "Department of Defense" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ↑ "Senate OKs defense bill, 68-29". TheHill. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ The New York Times, Pentagon Expected to Request More War Funding

- ↑ Gates ‘concerned’ about delayed war supplemental

- ↑ David Isenberg, Budgeting for Empire: The effect of Iraq and Afghanistan on Military Forces, Budgets and Plans

- ↑ Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments-Cost of the Iraq & Afghanistan Wars Through 2008

- ↑ Trotta, Daniel (29 June 2011). "Cost of war at least $3.7 trillion and counting". Reuters. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Historical Tables, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2015". United States Government Publishing Office. 2015. Retrieved 2015-01-13.

- ↑ "Death and Taxes". wallstats.com. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Intelligence Budget Data". Fas.org. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ↑ Defense Comptroller, FY 2011 Program Acquisition Costs by Weapon System

- ↑ Historical Outlays by Function and Subfunction, Archived on April 10, 2010 at the Internet Archive

- ↑ Historical Outlays by Agency

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "US Government's 2010 Financial Report Shows Significant Financial Management and Fiscal Challenges". US Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "FY 2010 DoD Agencywide Agency Financial Report (vid.)" (PDF). US Department of Defense. p. 25. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ "FY 2010 DoD Agencywide Agency Financial Report (vid. p.18)" (PDF). US Department of Defense. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ "FY 2010 DoD Agencywide Agency Financial Report (vid. p.32)" (PDF). US Department of Defense. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ "FY 2010 DoD Agencywide Agency Financial Report (vid. pp. 20, 28)" (PDF). US Department of Defense. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ "Significant Financial Management and Fiscal Challenges Reflected in the U.S. Government's 2011 Financial Report". US Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "DOD Financial Management: Ongoing Challenges with Reconciling Navy and Marine Corps Fund Balance with Treasury". US Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Sandra I. Erwin (June 2007). "More Services, Less Hardware Define Current Military Buildup". Defense Watch. National Defense Industrial Association. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ↑ "Secretary of Defense Testimony: Defense Budget Recommendation Statement (Arlington, VA)". defense.gov. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ Liebelson, Dana. "NYT Misses Elephant in the Room: Defense Service Contractors." POGO, 3 January 2012.

- ↑ "Monthly Budget Review" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ Congressional Appropriations: An Updated Analysis

- ↑ "Fiscal Year 2002 Budget". Center for Defense Information. Archived from the original on 2005-11-27. Retrieved 2006-07-13.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 The President's FY 2010 Budget

- ↑ Mike Carney (22 October 2007). "Bush submits $42.3B Iraq war supplemental funding bill". USA Today. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ AUGUST COLE (5 February 2008). "Bush's Successor to Confront Tough Decisions on Defense". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ Joint Chiefs Chairman Looks Beyond Current Wars

- ↑ "World Military Spending". globalissues.org. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ "World Wide Military Expenditures". GlobalSecurity.org. 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ↑ "The FY 2009 Pentagon Spending Request – Global Military Spending". armscontrolcenter.org. Center for Arms Control and Non-proliferation. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ "Tomgram: Nick Turse, The Pentagon's Planet of Bases". tomdispatch.com. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ CIA World Factbook. "Rank Order – Military expenditures percent of GDP". Retrieved 2006-05-26.

- ↑ "Relative Size of US Military Spending from 1940 to 2003". TruthAndPolitics.org.

- ↑ "Speech:". Defense.gov. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ↑ "Robert Gates follows through on his promises to reform the Pentagon". Slate Magazine. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ CRS Defense: FY2010 Authorization and Appropriations, pages 6–8

- ↑ Bender, Bryan. "Pentagon accused of end run on budget cuts." Boston Globe. 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Pellerin, Cheryl. "Carter: DOD Puts Strategy Before Budget for Future Force." American Forces Press Service, 30 May 2012.

- ↑ "Pentagon plan looks at lean, mean US army". The US News. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ "National Review". National Review Online. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ Wright, Robert (7 December 2012). "Why Not Push the Pentagon off the Fiscal Cliff?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ Martinez, Luis (5 December 2012). "Pentagon Begins Planning for $500B in ‘Fiscal Cliff’ Cuts". ABC. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ Mount, Mike (5 December 2012). "Pentagon told to start planning for fiscal cliff cuts". CNN. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "After months of delay, Pentagon told to plan for 'fiscal cliff'". Indian Express. 6 December 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ Alexander, David (5 December 2012). "UPDATE 2-After months of delay, Pentagon told to plan for 'fiscal cliff'". United Kingdom Reuters. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ SHERMAN, JAKE; JOHN BRESNAHAN and CARRIE BUDOFF BROWN (6 December 2012). "W.H. to House GOP: We're not moving". Politico Newspaper. p. 2. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ Darren Samuelsohn & Stephanie Gaskell. "Many old-time defense hawks take flight". POLITICO. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Pentagon faces a rebel yell over pensions". Financial Times. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ "US Government's 2010 Financial Report Shows Significant Financial Management and Fiscal Challenges". U.S. Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "FY 2011 DoD Agency Financial Report (vid. pp. 25–29)" (PDF). Comptroller, Department of Defense. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ "FY 2011 DoD Agencywide Agency Financial Report (vid. p.45)" (PDF). Comptroller, Department of Defense. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ "Financial Improvement and Audit Readiness (FIAR) Plan Status Report" (PDF). Comptroller, Department of Defense. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency Financial Report for FY 2011 (vid. p.46)" (PDF). Comptroller, Department of Defense. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency Financial Report for FY 2010 (vid. p.44)" (PDF). Comptroller, Department of Defense. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency Financial Report for FY 2009 (vid. p.23)" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "FY 2008 Agency Financial Report (vid. p.21)" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency Financial Report FY 2007 (vid. p.17)" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Performance and Accountability Report FY 2006 (vid. p.74)" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Performance and Accountability Report FY 2005 (vid. p.137)" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "FY 2004, FY 2003, FY 2002 Component Financial Statements". Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency-Wide Financial Statements Audit Opinion FY 2001" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency-Wide Financial Statements Audit Opinion FY 2000" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency-Wide Financial Statements Audit Opinion FY 1999" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "DoD Agency-Wide Financial Statements Audit Opinion FY 1998" (PDF). Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ "Gates Reveals Budget Efficiencies, Reinvestment Possibilities". US Department of Defense. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ Drwiega, Andrew. "Missions Solutions Summit: Army Leaders Warn of Rough Ride Ahead" Rotor&Wing, June 4, 2014. Accessed: June 8, 2014.

External links

- "Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)" Annual Department of Defense budget materials.

- Booknotes interview with Tim Weiner on Blank Check: The Pentagon's Black Budget, October 21, 1990.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||