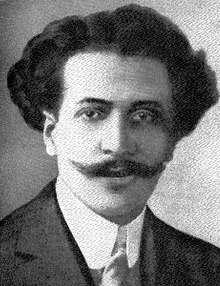

Miguel Almereyda

| Miguel Almereyda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Eugène Bonaventure Jean-Baptiste Vigo 3 January 1883 Béziers, Hérault, France |

| Died |

14 August 1917 (aged 34) Fresnes Prison, Fresnes, Val-de-Marne, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Photographer, journalist |

| Known for | Anti-militarism |

Eugène Bonaventure Jean-Baptiste Vigo (known as Miguel Almereyda; 5 January 1883 – 14 August 1917) was a French journalist and activist against militarism. He was first an anarchist and then a socialist. He founded and wrote in the newspaper La Guerre sociale and the satirical weekly Le Bonnet rouge. During World War I (1914–18) he engaged in dubious business dealings that brought him considerable wealth. He became engaged in a struggle with right-wing forces, and was eventually arrested on the grounds of being a German agent. He died in prison at the age of 34, almost certainly murdered. He was the father of the film director Jean Vigo.

Early years

Eugène Bonaventure Jean-Baptiste Vigo was born on 5 January 1883 in Béziers, Hérault. His father was engaged in trade, born in Saillagouse, and his mother Aimée Salles was a seamstress from Perpignan. The family originated in Err, Pyrénées-Orientales.[1] His grandfather, from a family of minor nobility, was the magistrate and military chief of Andorra. His father died young. His mother moved back to Perpignan, where she married Gabriel Aubès, a photographer.[2] Eugène Bonaventure remained with his mother's parents when his mother and stepfather moved to the Dordogne and then to Paris. He joined them there at the age of fifteen, and Aubès helped him gain an apprenticeship as a photographer. He struggled to make a living, but found friends in anarchist circles, including the slightly older Fernand Desprès, for which he became known to the police.[2]

Eugène Vigo was arrested in May 1900, ostensibly as an accessory in the receipt of stolen goods, but in fact for his anarchist activity. He served two months in prison at la Petite Roquette. It was here that he changed his name to "Miguel Almereyda". "Almereyda" is an anagram of "y'a la merde!" (there's shit) After being released he found work with a photographer on the Boulevard Saint-Denis, and published his first article in Le Libertaire in which he described plans to attack the judge who had convicted him with a bomb. This fizzled out, but in the summer of 1901 the police found explosives in his room.[3] Almereyda was sentenced to a year in prison. He was released after serving most of his sentence, and again found work with a photographer.[4]

Militant journalist

Almereyda again began writing for Le Libertaire, and by the start of 1903 was one of the most prolific of the journal's writers. In March 1903 he gave up photography to devote himself to journalism and political activism.[4] Around this time he fell in love with Emily Cléro, a young militant, and they began to live together.[5] The Ligue antimilitariste was founded in December 1902 by the anarchists Georges Yvetot, Henri Beylie, Paraf-Javal, Albert Libertad and Émile Janvion. This became the French section of the Association internationale antimilitariste (AIA), which was the subject of intense police surveillance.[6] In 26–28 June 1904 the AIA held its founding congress in Amsterdam, with a 12-member delegation from France. Yvetot and Almereyda led the French section and sat on the AIA committee. The congress was dominated by anarchists, but also included syndicalists and communists. The question of whether refusal of military service should be AIA strategy was hotly debated.[7]

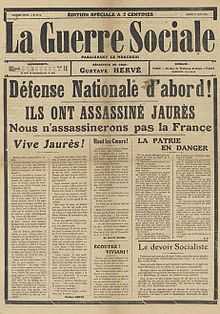

In April 1905 Almereyda's companion Emily Cléro gave birth to a son, whom they called Jean.[8] In the fall of 1905 Almereyda and Gustave Hervé plastered AIA posters all over Paris urging young men to resist conscription with violence if needed. They were charged for this, and on 30 December 1905 were found guilty and sent to Clairvaux prison. They and others were freed on 14 July 1906 in an amnesty. At the end of 1906 Almereyda and Eugène Merle founded La Guerre Sociale (The Social War), a weekly paper, with Hervė as the principal editor. In April 1908 Almereyda was sentenced to two years in prison for praising the mutiny of the 17th Battalion at Narbonne, with another year added for having criticized the French expedition to Morocco.[9]

Almereyda remained in prison until August 1909. After his release he began discussing formation of a Revolutionary Party. He was leader of the "Liabeuf" affair, in which a large crowd demonstrated over the execution of a young cobbler, and a detective was killed.[10] Hervé was arrested for an article defending Liabeuf and was given a long prison sentence. During the railway strike of October 1910 Almereyda and Merle formed a group to organize sabotage, and were arrested and imprisoned until March 1911. On his release Almereyda founded the revolutionary group les Jeunes gardes révolutionnaires.[11] La Guerre Sociale steadily became less revolutionary and more a supporter of left-wing republican ideals to be achieved legally. In December 1912 Almereyda joined the Socialist Party. By 1913 La Guerre Sociale had a circulation of 50,000, and Almereyda had a growing reputation in respectable liberal circles.[12]

Almereyda launched Le Bonnet rouge, a satirical anarchist publication, on 22 November 1913. The journal, "organ of the Republican defense", was the sworn enemy of the right-wing monarchist political movement Action Française. It began as a weekly paper, and quickly became popular. It became a daily in March 1914.[13] Le Bonnet rouge published articles at the request of the Finance Minister Joseph Caillaux that defended his wife, Henriette Caillaux. She was accused of murdering Gaston Calmette, director of Le Figaro. Calmette had led a violent campaign against Caillaux, whom he accused of a policy of rapprochement with the Germans. Madame Caillaux had murdered him in a moment of madness.[13]

World War I

With the outbreak of war Le Bonnet Rouge and La Guerre Sociale accepted the need to fight to defend the country. After visiting the battlefields, Almereyda became convinced of the horrors of war, which he discussed in his articles, but also of the need to defend the republic and the government against extreme right-wing forces.[14] The Interior Minister Louis Malvy gave a subsidy to Almereyda and Le Bonnet Rouge on the grounds that although they would criticize the war they would discourage violent opposition to the war, a tactic he called co-opting the left.[15]

Almereyda began to use Le Bonnet Rouge to advance various business interests, using the money for his personal use and to support the paper. Thus, he abandoned a campaign against alcohol when Pernod began giving the paper subsidies. By 1915 he was leading a lavish lifestyle, with a car, mistresses and a private mansion.[16] Almereyda suffered from nephritis.[17] His health deteriorated and he began taking morphine to relieve pain.[18]

In June 1915 Almereyda became involved in an increasingly vicious struggle with the L'Action Française movement. Léon Daudet, editor of the movement's journal L'Action Française, described Almereyda as "Vigo the Traitor" and made vague insinuations about Almereyda's reasons for using a pseudonym.[19] Le Bonnet Rouge became more and more critical of the conduct of the war. It made much of US President Woodrow Wilson's effort to have the belligerents declare their goals in preparation for a peace conference. It published Lenin's explanations of his goals in Russia. To the right wing, Lenin was a German agent. The paper lost its government subsidy and was subject to growing censorship.[18] Between July 1916 and July 1917, when Le Bonnet Rouge was closed down, the censors blanked out 1,076 of the paper's articles.[17]

In July 1917 the business administrator of Le Bonnet Rouge was arrested on his return from a trip to Switzerland, and was found to have a check on a German bank account for 100,000 francs. Almereyda faced a furious attack from the far right and from Georges Clemenceau. Almereyda's political allies Louis Malvy and Joseph Cailloux were accused of commerce with the enemy. Almerayda was arrested and sent to La Santé Prison in the 14th arrondissement.[20] Due to his health problems he was transferred to Fresnes Prison outside Paris.[21] In the morning of 14 August 1917 he was found dead in his cell, strangled with his bootlaces. The cause of death was given as suicide, but he had almost certainly been murdered.[13] The autopsy found that his abdomen was full of pus and he was struggling with a burst appendix.[17]

Almereyda's son Jean Vigo later became a well-known film director.[22] He had been profoundly affected by his turbulent childhood, and was always convinced that his father was innocent. The influence of Almereyda shows clearly in several of Vigo's films such as À propos de Nice, Zéro de conduite and L'Atalante.[21]

Publications

- Almereyda, Miguel (1906). Le Procès des quatre : [Malato, Vallina, Harvey, Caussanel]. Paris: Libertaire. p. 32.

- Almereyda, Miguel (1915). Les naufrageurs de la Patrie: le Bonnet Rouge contre l'Action Française. Éd. du "Bonnet Rouge". p. 64.

References

- ↑ Pelayo 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gomes 1971, p. 9.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 10.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gomes 1971, p. 11.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 12.

- ↑ Miller 2002, p. 38.

- ↑ Miller 2002, p. 41.

- ↑ Ronsin & Ubeda 2008.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 14.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 15.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 16.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 17.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Ladjimi 2008, p. 4.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 18.

- ↑ Fleming 2008, p. 168.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 20.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 White & Buscombe 2003, p. 291.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Gomes 1971, p. 23.

- ↑ Gomes 1971, p. 21.

- ↑ Temple 2005, p. 5.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Temple 2005, p. 6.

Sources

- Fleming, Thomas (2008-08-05). The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-2498-7. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- Gomes, Paulo Emílio Salles (1971-01-01). Jean Vigo. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01676-7. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- Ladjimi, C.E. (2008). "Affaire du " Bonnet rouge "" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- Miller, Paul B. (2002-03-14). From Revolutionaries to Citizens: Antimilitarism in France, 1870–1914. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-8058-7. Retrieved 2014-12-03.

- Pelayo, Donato (2011-06-26). "Jules Montels: une vie d’éternel rebelle". What's new (in French). Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- Ronsin, Francis; Ubeda, Isabelle (2008-01-25). "HUMBERT, Jeanne". Archives de l’Institut International d’Histoire Sociale, Amsterdam. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- Temple, Michael (2005). Jean Vigo. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5632-1. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- White, Rob; Buscombe, Edward (2003). "La Bande À Vigo". British Film Institute Film Classics. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-57958-328-6. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

|