Microfiltration

Microfiltration (commonly abbreviated to MF) is a type of physical filtration process where a contaminated fluid is passed through a special pore-sized membrane to separate microorganisms and suspended particles from process liquid. It is commonly used in conjunction with various other separation processes such as ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis to provide a product stream which is free of undesired contaminants.

General Principles

Microfiltration usually serves as a pre-treatment for other separation processes such as ultrafiltration, and a post-treatment for granular media filtration. The typical particle size used for microfiltration ranges from about 0.1 to 10 µm.[1] In terms of approximate molecular weight these membranes can separate macromolecules generally less than 100,000 g/mol.[2] The filters used in the microfiltration process are specially designed to prevent particles such as, sediment, algae, protozoa or large bacteria from passing through a specially designed filter. More microscopic, atomic or ionic materials such as water (H2O), monovalent species such as Sodium (Na+) or Chloride (Cl−) ions, dissolved or natural organic matter, and small colloids and viruses will still be able to pass through the filter.[3]

The suspended liquid is passed though at a relatively high velocity of around 1–3 m/s and at low to moderate pressures (around 100-400 kPa) parallel or tangential to the semi-permeable membrane in a sheet or tubular form.[4] A pump is commonly fitted onto the processing equipment to allow the liquid to pass through the membrane filter. There are also two pump configurations, either pressure driven or vacuum. A differential or regular pressure gauge is commonly attached to measure the pressure drop between the outlet and inlet streams. See Figure 1 for a general setup.[5]

The most abundant use of microfiltration membranes are in the water, beverage and bio-processing industries (see below). The exit process stream after treatment using a micro-filter has a recovery rate which generally ranges to about 90-98 %.[6]

Range of Applications

Water Treatment

Perhaps the most prominent use of microfiltration membranes pertains to the treatment of potable water supplies. The membranes are a key step in the primary disinfection of the uptake water stream. Such a stream might contain pathogens such as the protozoa Cryptosporidium and Giardia lamblia which are responsible for numerous disease outbreaks. Both species show a gradual resistance to traditional disinfectants (i.e. chlorine).[7] The use of MF membranes presents a physical means of separation (a barrier) as opposed to a chemical alternative. In this sense, both filtration and disinfection take place in a single step, negating the extra cost of chemical dosage and the corresponding equipment (needed for handling and storage).

Similarly, the MF membranes are used in secondary wastewater effluents to remove turbidity but also to provide treatment for disinfection. At this stage, coagulants (iron or aluminum) may potentially be added to precipitate species such as phosphorus and arsenic which would otherwise have been soluble.

Sterilization

Another crucial application of MF membranes lies in the cold sterilisation of beverages and pharmaceuticals.[8] Historically, heat was used to sterilize refreshments such as juice, wine and beer in particular, however a palatable loss in flavour was clearly evident upon heating. Similarly, pharmaceuticals have been shown to lose their effectiveness upon heat addition. MF membranes are employed in these industries as a method to remove bacteria and other undesired suspensions from liquids, a procedure termed as ‘cold sterilisation’, which negate the use of heat.

Petroleum Refining

Furthermore, microfiltration membranes are finding increasing use in areas such as petroleum refining,[9] in which the removal of particulates from flue gases is of particular concern. The key challenges/requirements for this technology are the ability of the membrane modules to withstand high temperatures (i.e. maintain stability), but also the design must be such to provide a very thin sheeting (thickness < 2000 angstroms) to facilitate an increase of flux. In addition the modules must have a low fouling profile and most importantly, be available at a low-cost for the system to be financially viable.

Dairy Processing

Aside from the above applications, MF membranes have found dynamic use in major areas within the dairy industry, particularly for milk and whey processing. The MF membranes aid in the removal of bacteria and the associated spores from milk, by rejecting the harmful species from passing through. This is also a precursor for pasteurisation, allowing for an extended shelf-life of the product. However, the most promising technique for MF membranes in this field pertains to the separation of casein from whey proteins (i.e. serum milk proteins).[10] This results in two product streams both of which are highly relied on by consumers; a casein-rich concentrate stream used for cheese making, and a whey/serum protein stream which is further processed (using ultrafiltration) to make whey protein concentrate. The whey protein stream undergoes further filtration to remove fat in order to achieve higher protein content in the final WPC (Whey Protein Concentrate) and WPI (Whey Protein Isolate) powders.

Other Applications

Other common applications utilising microfiltration as a major separation process include

- Clarification and purification of cell broths where macromolecules are to be separated from other large molecules, proteins, or cell debris.[11]

- Other biochemical and bio-processing applications such as clarification of dextrose.[12]

- Production of Paints and Adhesives.[13]

Main Process Characteristics

Membrane filtration processes can be distinguished by three major characteristics; Driving force, retentate stream and permeate streams. The microfiltration process is pressure driven with suspended particles and water as retentate and dissolved solutes plus water as permeate. The use of hydraulic pressure accelerates the separation process by increasing the flow rate (flux) of the liquid stream but does not affect the chemical composition of the species in the retentate and product streams.[14]

A major characteristic that limits the performance of microfiltration or any membrane technology is a process known as fouling. Fouling describes the deposition and accumulation of feed components such as suspended particles, impermeable dissolved solutes or even permeable solutes, on the membrane surface and or within the pores of the membrane. Fouling of the membrane during the filtration processes decreases the flux and thus overall efficiency of the operation. This is indicated when the pressure drop increases to a certain point. It occurs even when operating parameters are constant (pressure, flow rate, temperature and concentration) Fouling is mostly irreversible although a portion of the fouling layer can be reversed by cleaning for short periods of time.[15]

Microfiltration membranes can generally operate in one of two configurations.

Cross-flow filtration: where the fluid is passed through tangentially with respect to the membrane.[16] Part of the feed stream containing the treated liquid is collected below the filter while parts of the water are passed through the membrane untreated. Cross flow filtration is understood to be a unit operation rather than a process. Refer to Figure 2 for a general schematic for the process.

Dead-end filtration; all of the process fluid flows and all particles larger than the pore sizes of the membrane are stopped at its surface. All of the feed water is treated at once subject to cake formation.[17] This process is mostly used for batch or semicontinuous filtration of low concentrated solutions,[18] Refer to Figure 3 for a general schematic for this process.

NOTE: Figures 2 and 3 are missing from the article

Process and Equipment Design

The major issues which influence the selection of the membrane include [19]

Site Specific Issues (Unique to the site where the plant is located)

- Capacity and demand of the facility.

- Percentage recovery and rejection.

- Fluid characteristics (viscosity, turbidity, density)

- Quality of the fluid to be treated

- Pre-treatment processes

Membrane Specific Issues (Unique to the manufacturer or supplier)

- Cost of material procurement and manufacture

- Operating temperature

- Trans-membrane pressure

- Membrane flux

- Handling fluid characteristics (Viscosity, Turbidity, Density)

- Monitoring and maintenance of the system

- Cleaning and treatment

- Disposal of process residuals

Process Design Variables (Regarding proper membrane selection)

- Operation and control of all processes in the system,

- Materials of construction

- Equipment and instrumentation (controllers, sensors) and their cost.

Fundamental Design Heuristics

A few important design heuristics and their assessment are discussed below:

- When treating raw contaminated fluids, hard sharp materials can wear and tear the porous cavities in the micro-filter, rendering it ineffective. Liquids must be subjected to pre-treatment before passage through the micro-filter.[20] This may be achieved by a variation of macro separation processes such as screening, or granular media filtration.

- When undertaking cleaning regimes the membrane must not dry out once it has been contacted by the process stream.[21] Thorough water rinsing of the membrane modules, pipelines, pumps and other unit connections should be carried out until the end water appears clean.

- Microfiltration modules are typically set to operate at pressures of 100 to 400 kPa.[22] These pressures allow removal of materials such as sand, slits and clays, and also bacteria and protozoa.

- When the membrane modules are being used for the first time, i.e. during plant start-up, conditions need to be well devised. Generally a slow-start is required when the feed is introduced into the modules, since even slight perturbations above the critical flux will result in irreversible fouling.[23]

Like any other membranes Microfiltration membranes are prone to fouling. (See Figure 4 below) It is therefore necessary that regular maintenance be carried out to prolong the life of the membrane module.

- Routine ‘backwashing’, is used to achieve this. Depending on the specific application of the membrane, backwashing is carried out in short durations (typically 3 to 180 s) and in moderately frequent intervals (5 min to several hours). Turbulent flow conditions with Reynolds numbers greater than 2100, ideally between 3000 - 5000 should be used.[24] This should not however be confused with ‘backflushing’, a more rigorous and thorough cleaning technique, commonly practiced in cases of particulate and colloidal fouling.

- When major cleaning is needed to remove entrained particles, a CIP (Clean In Place) technique is used.[25] Cleaning agents/detergents, such as sodium hypochlorite, citric acid, caustic soda or even special enzymes are typically used for this purpose. The concentration of these chemicals is dependent on the type of the membrane (its sensitivity to strong chemicals), but also the type of matter (e.g. scaling due to the presence of calcium ions) to be removed.

- Another method to increase the lifespan of the membrane may be feasible to design two microfiltration membranes in series. The first filter would be used for pre-treatment of the liquid passing though the membrane, where larger particles and deposits are captured on the cartridge. The second filter would act as an extra “check” for particles which are able to pass through the first membrane as well as provide screening for particles on the lower spectrum of the range.[26]

Design Economics

The cost to design and manufacture a membrane per unit of area are about 20% less compared to the early 1990s and in a general sense are constantly declining.[27] Microfiltration membranes are more advantageous in comparison to conventional systems. Microfiltration systems do not require expensive extraneous equipment such as flocculates, addition of chemicals, flash mixers, settling and filter basins.[28] However the cost of replacement of capital equipment costs (membrane cartridge filters etc.) might still be relatively high as the equipment may be manufactured specific to the application. Using the design heuristics and general plant design principles (mentioned above), the membrane life-span can be increased to reduce these costs.

Through the design of more intelligent process control systems and efficient plant designs some general tips to reduce operating costs are listed below[29]

- Running plants at reduced fluxes or pressures at low load periods (winter)

- Taking plant systems off-line for short periods when the feed conditions are extreme.

- A short shutdown period (approximately 1 hour) during the first flush of a river after rainfall (in water treatment applications) to reduce cleaning costs in the initial period.

- The use of more cost effective cleaning chemicals where suitable (sulphuric acid instead of citric/ phosphoric acids.)

- The use of a flexible control design system. Operators are able to manipulate variables and setpoints to achieve maximum cost savings.

Table 1 (below) expresses an indicative guide of membrane filtration capital and operating costs per unit of flow.

| Parameter | Amount | Amount | Amount | Amount | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design Flow (mg/d) | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 10 | 100 |

| Average Flow (mg/d) | 0.005 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 4.4 | 50 |

| Capital Cost ($/gal) | $18.00 | $4.30 | $1.60 | $1.10 | $0.85 |

| Annual Operating and Managing Costs ($/kgal) | $4.25 | $1.10 | $0.60 | $0.30 | $0.25 |

Table 1 Approximate Costing of Membrane Filtration per unit of flow[30]

Note:

- Capital Costs are based on dollars per gallon of the treatment plant capacity

- Design flow is measured in millions of gallons per day.

- Membrane Costs only (No Pre-Treatment or Post-Treatment equipment considered in this table)

- Operating and Annual costs, are based on dollars per thousand gallons treated.

- All prices are in US dollars current of 2009, and is not adjusted for inflation.

Process Equipment

Membrane Materials

The materials which constitute the membranes used in microfiltration systems may be either organic or inorganic depending upon the contaminants that are desired to be removed, or the type of application.

- Organic membranes are made using a diverse range of polymers including cellulose acetate (CA), polysulfone, polyvinylidene fluoride, polyethersulfone and polyamide. These are most commonly used due to their flexibility, and chemical properties.[4]

- Inorganic membranes are usually composed of sintered metal or porous alumina. They are able to be designed in various shapes, with a range of average pore sizes and permeability.[4]

Membrane Equipment

General Membrane structures for microfiltration include

- Screen filters (Particles and matter which are of the same size or larger than the screen openings are retained by the process and are collected on the surface of the screen)

- Depth filters (Matter and particles are embedded within the constrictions within the filter media, the filter surface contains larger particles, smaller particles are captured in a narrower and deeper section of the filter media.)

Microfiltration Membrane Modules

Plate and frame (flat sheet)

Membrane modules for dead-end flow microfiltration are mainly plate-and-frame configurations. They possess a flat and thin-film composite sheet where the plate is asymmetric. A thin selective skin is supported on a thicker layer that has larger pores. These systems are compact and possess a sturdy design, Compared to cross-flow filtration, plate and frame configurations possess a reduced capital expenditure; however the operating costs will be higher. The uses of plate and frame modules are most applicable for smaller and simpler scale applications (laboratory) which filter dilute solutions.[31]

Spiral-wound

This particular design is used for cross-flow filtration. The design involves a pleated membrane which is folded around a perforated permeate core, akin to a spiral, that is usually placed within a pressure vessel. This particular design is preferred when the solutions handled is heavily concentrated and in conditions of high temperatures and extreme pH. This particular configuration is generally used in more large scale industrial applications of microfiltration.[31]

Fundamental Design Equations

As separation is achieved by sieving, the principle mechanism of transfer for microfiltration through micro porous membranes is bulk flow.[32]

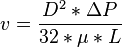

Generally, due to the small diameter of the pores the flow within the process is laminar (Reynolds Number < 2100) The flow velocity of the fluid moving through the pores can thus be determined (by Hagen-Poiseuille’s equation), the simplest of which assuming a parabolic velocity profile.

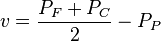

Transmembrane Pressure (TMP)[33]

The transmembrane pressure (TMP) is defined as the mean of the applied pressure from the feed to the concentrate side of the membrane subtracted by the pressure of the permeate. This is applied to dead-end filtration mainly and is indicative of whether a system is fouled sufficiently to warrant replacement.

Where

- P_f is the pressure on the Feed Side

- P_c is the pressure of the Concentrate

- P_p is the pressure of the Permeate

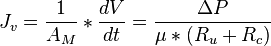

Permeate Flux [34]

The permeate flux in microfiltration is given by the following relation, based on Darcy’s Law

Where

- Ru = Permeate membrane flow resistance (m-1)

- Rc = Permeate cake resistance (m-1)

- μ = Permeate viscosity (kg m-1s-1)

- ∆P = Pressure Drop between the cake and membrane

The cake resistance is given by:

Where

- r = Specific cake resistance (m-2)

- Vs = Volume of cake (m3)

- AM = Area of membrane (m2)

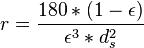

For micron sized particles the Specific Cake Resistance is roughly.[35]

Where

- ε = Porosity of cake (unitless)

- d_s = Mean particle diameter (m)

Rigorous design equations[36]

To give a better indication regarding the exact determination of the extent of the cake formation, one-dimensional quantitative models have been formulated to determine factors such as

- Complete Blocking (Pores with an initial radius less that the radius of the pore)

- Standard Blocking

- Sublayer Formation

- Cake Formation

See External Links for further details

Environmental Issues, Safety and Regulation

Although environmental impacts of membrane filtration processes differs between applications a generic method of evaluation is the Life-cycle assessment (LCA), a tool for the analysis of the environmental burden of membrane filtration processes at all stages. It accounts for all types of impacts upon the environment including emission to land, water and air.

In regards to microfiltration processes there are a number of potential environmental impacts to be considered. They include: global warming potential, photo – oxidant formation potential, eutrophication potential, human toxicity potential, freshwater ecotoxicity potential, marine ecotoxicity potential and terrestrial ecotoxicity potential. In general, the potential environmental impact of the process is largely dependent on flux and the maximum transmembrane pressure, however other operating parameters remain a factor to be considered. A specific comment on which exact combination of operational condition will yield the lowest burden on the environment cannot be made as each application will require different optimisations.[37]

In a general sense, membrane filtration processes are relative “low risk” operations, that is, the potential for dangerous hazards are small. There are, however several aspects to be mindful of. All pressure – driven filtration processes including microfiltration requires a degree of pressure to be applied to the feed liquid stream as well as imposed electrical concerns. Other factors contributing to safety are dependent on parameters of the process. For example, processing dairy product will lead to bacteria formations that must be controlled to comply with safety and regulatory standards.[38]

Comparison with Similar Processes

Membrane microfiltration is fundamentally the same as other filtration techniques utilising a pore size distribution to physically separate particles. It is analogous to other technologies such as ultra/nanofiltration and reverse osmosis, however, the only difference exists in the size of the particles retained, and also the osmotic pressure. The main of which are described in general below:

Ultrafiltration (UF)

Ultrafiltration membranes have pore sizes ranging from 0.1 µm to 0.01 µm and are able to retain proteins, endotoxins, viruses and silica. UF has diverse applications which span from waste water treatment to pharmaceutical applications.

Nanofiltration (NF)

Nanofiltration membranes have pores sized from 0.001 µm to 0.01 µm and filters multivalent ions, synthetic dyes, sugars and specific salts. As the pore size drops from MF to NF, the osmotic pressure requirement increases.

Reverse Osmosis (RO)

Reverse Osmosis is the finest separation membrane process available, pore sizes range from 0.0001 µm to 0.001 µm. RO is able to retain mostly all molecules except for water and due to the size of the pores, the required osmotic pressure is significantly greater than that for MF. Both reverse osmosis and nanofiltration are fundamentally different since the flow goes against the concentration gradient, because those systems use pressure as a means of forcing water to go from low pressure to high pressure.

Recent Developments

Recent advances in MF have focused on manufacturing processes for the construction of membranes and additives to promote coagulation and therefore the fouling of the membrane. Since MF, UF, NF and RO are closely related, these advances are applicable to multiple processes and not MF alone.

Recently studies have shown dilute KMnO4 preoxidation combined FeCl3 is able to promote coagulation, leading to decreased fouling, in specific the KMnO4 preoxidation exhibited an effect which decreased irreversible membrane fouling.[39]

Similar research has been done into the construction high flux poly(trimethylene terephthalate) (PTT) nanofiber membranes, focusing on increased throughput. Specialised heat treatment and manufacturing processes of the membrane’s internal structure exhibited results indicating a 99.6% rejection rate of TiO2 particles under high flux. The results indicate that this technology may be applied to existing applications to increase their efficiency via high flux membranes.[40]

See also

- Membrane Technology

- Ultrafiltration

- Nanofiltration

- Reverse osmosis

- Membrane bioreactor

References

- ↑ Baker, R 2012, Microfiltration, in Membrane Technology and Applications, 3rd edn, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, California. p. 303

- ↑ Microfiltration/Ultrafiltration, 2008, Hyflux Membranes, accessed 27 September 2013. <http://www.hyfluxmembranes.com/microfiltration.html rel="nofollow>"

- ↑ Crittenden, J, Trussell, R, Hand, D, Howe, K & Tchobanoglous, G. 2012, Principles of Water Treatment, 2nd edn, John Wiley and Sons, New Jersey. 8.1

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Perry, RH & Green, DW, 2007. Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 8th Edn. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York. p. 2072

- ↑ Baker, R 2000, Microfiltration, in Membrane Technology and Applications, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, California. p. 279.

- ↑ Kenna,E & Zander, A 2000, Current Management of Membrane Plant Concentrate, American Waterworks Association, Denver. p.14

- ↑ Water Treatment Solutions. 1998, Lenntech, accessed 27 September 2013 <http://www.lenntech.com/microfiltration.htm

- ↑ Veolia Water, Pharmaceutical & Cosmetics. 2013, Veolia Water, accessed 27 September 2013. Available from: <http://www.veoliawaterst.com/industries/pharmaceutical-cosmetics/.>

- ↑ Baker, R.,3rd ed, Microfiltration, in Membrane Technology and Applications John Wiley & Sons Ltd: California. p. 303-324.

- ↑ GEA Filtration - Dairy Applications. 2013, GEA Filtration, accessed 26 September 2013, <http://www.geafiltration.com/applications/industrial_applications.asp.>

- ↑ Baker, R 2012, Microfiltration, in Membrane Technology and Applications, 3rd edn, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, California. p. 303-324.

- ↑ Valentas J., Rotstein E, & Singh, P 1997, Handbook of Food Engineering Practice, CRC Press LLC, Florida, p.202

- ↑ Starbard, N 2008, Beverage Industry Microfiltration, Wiley Blackwell, Iowa. p.4

- ↑ Cheryan, M 1998, Fouling and Cleaning. in Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Handbook 2nd edn., CRC Press, Florida, p.1-9.

- ↑ Cheryan, M 1998, 'Fouling and Cleaning. in Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Handbook' 2nd edn., CRC Press, Florida, p.1-9.

- ↑ Perry, RH & Green, DW, 2007. Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 8th Edn. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York. p 2072-2100

- ↑ Perry, RH & Green, DW, 2007. Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook, 8th Edn. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York. p2072-2100

- ↑ Seadler ,J & Henley, E 2006, Separation Process Principles, 2nd Edn, John Wiley & Sons Inc. New Jersey. p.501

- ↑ American Water Works Association, 2005. Microfiltration and Ultrafiltration Membranes in Drinking Water (M53) (Awwa Manual) (Manual of Water Supply Practices). 1st edn.. American Waterworks Association. Denver. p 165

- ↑ Water Treatment Solutions. 1998, Lenntech, accessed 27 September 2013 < http://www.lenntech.com/microfiltration.htm

- ↑ Cheryan, M 1998, Fouling and Cleaning. 2nd edn. Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Handbook, CRC Press, Florida p. 237-278

- ↑ Baker, R 2012, Microfiltration, in Membrane Technology and Applications, 3rd edn, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, California p. 303-324

- ↑ Cheryan, M 1998, Fouling and Cleaning. 2nd edn. Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Handbook, CRC Press, Florida p 237-278

- ↑ Cheryan, M 1998, Fouling and Cleaning. in Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Handbook 2nd edn., CRC Press, Florida, p. 237-278

- ↑ Baker, R 2012, Microfiltration, in Membrane Technology and Applications, 3rd edn, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, California. p. 303-324

- ↑ Baker, R 2000, Microfiltration, in Membrane Technology and Applications, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, California. p. 280

- ↑ Mullenberg 2009, ‘Microfiltration: How Does it compare, Water and wastes digest, web log post, December 28, 2000, accessed 3 October 2013,<http://www.wwdmag.com/desalination/microfiltration-how-does-it-compare.>

- ↑ Layson A, 2003, Microfiltration – Current Know-how and Future Directions, IMSTEC, accessed 01 October 2013 http://www.ceic.unsw.edu.au/centers/membrane/imstec03/content/papers/MFUF/imstec152.pdf> University of New South Wales. p6

- ↑ Layson A, 2003, Microfiltration – Current Know-how and Future Directions, IMSTEC, accessed 01 October 2013 <http://www.ceic.unsw.edu.au/centers/membrane/imstec03/content/papers/MFUF/imstec152.pdf> University of New South Wales. p6

- ↑ Microfiltration/Ultrafiltration, 2009, Water Research Foundation, accessed 26 September 2013; <http://www.simultaneouscompliancetool.org/SCToolSmall/jsp/modules/welcome/documents/TECH7.pdf>

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Seadler ,J & Henley, E 2006, Separation Process Principles, 2nd Edn, John Wiley & Sons Inc. New Jersey p.503

- ↑ Seadler ,J & Henley, E 2006, Separation Process Principles, 2nd Edn, John Wiley & Sons Inc. New Jersey p.540-542

- ↑ Cheryan, M 1998, Fouling and Cleaning. in Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Handbook 2nd edn., CRC Press, Florida, 645.

- ↑ Ghosh, R, 2006, Principles of Bioseparations Engineering, Word Scientific Publishing Co.Pte.Ltd, Toh Tuck Link, p.233

- ↑ Ghosh, R, 2006,Principles of Bioseparations Engineering, Word Scientific Publishing Co.Pte.Ltd, Toh Tuck Link, p.234

- ↑ Polyakov, Yu, Maksimov, D & Polyakov, V, 1998 ‘On the Design of Microfilters’ Theoretical Foundations of Chemical Engineering, Vol. 33, No. 1, 1999, pp. 64–71.

- ↑ Tangsubkul, N, Parameshwaran , K, Lundie, S, Fane,AG & Waite, TD 2006 , ‘Environmental life cycle assessment of the microfiltration process’, Journal of Membrane Science vol. 284, pp. 214–226

- ↑ Cheryan, M 1998, Fouling and Cleaning. 2nd edn. Ultrafiltration and Microfiltration Handbook, CRC Press, Florida, p. 352-407.

- ↑ Tian, J, Ernst, M, Cui, F, & Jekel, M 2013 ‘KMnO4 pre-oxidation combined with FeCl3 coagulation for UF membrane fouling control’, Desalination, vol. 320, 1 July, pp 40-48,

- ↑ Li M, Wang ,D, Xiao, R ,Sun, G, Zhao, Q & Li, H 2013 ‘A novel high flux poly(trimethylene terephthalate) nanofiber membrane for microfiltration media’, Separation and Purification Technology, vol. 116, 15 September, pp 199-205

External links

Polyakov, Yu, Maksimov, D, & Polyakov, V, 1998 ‘On the Design of Microfilters’ Theoretical Foundations of Chemical Engineering, Vol. 33, No. 1, 1999. < http://web.njit.edu/~polyakov/docs/Microfiltration_TFCE_English.pdf>

Layson A, 2003, Microfiltration – Current Know-how and Future Directions, IMSTEC, accessed 1 October 2013 http://www.ceic.unsw.edu.au/centers/membrane/imstec03/content/papers/MFUF/imstec152.pdf> University of New South Wales Chemical Engineering Website.