Michel-Joseph Maunoury

| Michel-Joseph Maunoury | |

|---|---|

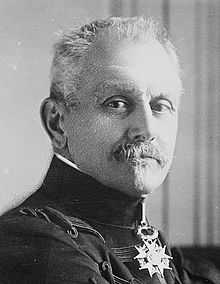

General Maunoury | |

| Born |

17 December 1847 Maintenon |

| Died | 28 March 1923 (aged 75) |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | French Army |

| Years of service | 1876–1920 |

| Rank | Marshal of France |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Awards | Marshal of France (posthumous) |

Michel-Joseph Maunoury (17 December 1847 – 28 March 1923) was a commander of French forces in the early days of World War I.

Initially commanding in Lorraine, as the success of the German thrust through Belgium became clear he was sent to take command of the new Sixth Army which was assembling near Amiens. The Sixth Army played an important role in the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914. With a small portion of its strength rushed to the front in commandeered taxicabs, it attacked von Kluck's German First Army from the west at the Battle of the Ourcq. Although the attack did not succeed, the resulting German redeployment opened up a gap which was exploited by French Fifth Army and the small British Expeditionary force, ultimately causing the Germans to retreat.

Prewar career

Maunoury was born on 17 December 1847.[1]

He was wounded as a lieutenant in the Franco-Prussian War.[2][3] He was a Polytechnician and an artillery specialist.[4] He studied at the Ecole de Guerre, and was then an instructor at St Cyr before becoming a full colonel.[5]

He commanded an artillery brigade then from 1905 commanded III then XX Corps.[6] He was a member of the Conseil Superieur de la Guerre and was then Military Governor of Paris.[7] He was earmarked for command of an army in the event of war, but retired in 1912.[8]

He is described by Holger Herwig as “slender, almost delicate”[9] and by Tuchman as “svelte, delicate, small-boned”.[10]

First World War

Lorraine

Main Articles: Plan XVII , Battle of the Ardennes

As Third and Fourth Armies thrust into the Ardennes (the Commander-in-Chief Joffre issued orders on 20 August, for operations to begin on 22 August) they opened up a potential gap between Third Army’s right and the left of Second Army, which had just launched an unsuccessful attack into Lorraine. So Joffre created an Army of Lorraine at Verdun to fill the gap, including three divisions taken from Third Army. Maunoury was recalled from retirement to command it.[11] The Army of Lorraine had seven divisions in total, three of them from Ruffey. It consisted of Bonneau’s VII Corps, which had begun the war with a move into Alsace, and 55th and 56th Reserve Divisions from Ruffey’s Third Army. [12] Joffre’s Ordre Particuliere no 18 (21 August), ordered the Army of Lorraine to “fix” as many Germans as possible.[13]

The Army of Lorraine consisted entirely of reserve divisions. Ruffey was not initially aware of its existence. [14] At 1.30pm on 22 August Ruffey begged for help – Maunoury sent Jules Chailley’s 54th Reserve Infantry Division and Henri Marabail’s 67th Reserve Infantry Division. This proved not enough to rescue Ruffey’s offensive.[15]

Redeployment to the West

After meeting with Sir John French and Lanrezac (commander of Fifth Army), who were barely on speaking terms, at St Quentin on the morning of 26 August, and hearing reports (which later turned out to be exaggerated) of the destruction of British II Corps at Le Cateau, Joffre became deeply concerned at the weakness of his left flank and the risk of the British Expeditionary Force being overrun. That night he enacted Instruction No 2, ordering a new army to be formed under Maunoury around Amiens on the French west flank, consisting of four reserve divisions and a corps. He also dissolved the Army of Lorraine and sent its staff to Maunoury’s new army, although not its divisions which were reabsorbed into Third Army. He also dissolved Pau’s Army of Alsace.[16][17][18]

Joffre had little choice but to deploy reserve divisions in the front line. Ebener’s Sixth Group, consisting of 61st and 62nd Infantry Divisions, both reserve formations, which had made up the Paris Garrison before being railed to Arras, were ordered to march south to block the German advance on Bapaume and Peronne (the future Somme battlefield of 1916). Marching down from Cambrai to link up with Maunoury’s forces, they brushed aside a German cavalry screen and entered Bapaume, then on 28 August as the fog lifted they were ambushed by Linsingen’s II Corps at Moislains north of Peronne (and near Sailly-Saillisel, which was to be the scene of French operations on the Somme in 1916). 62nd Division retreated north back to Arras, 61st retreated to Amiens. Further south Peronne fell.[19]

Maunoury’s army, initially called the “Army of Manoeuvre”, began as a collection of 80,000 reservists and second line troops, before being reinforced with troops redeployed by rail from Lorraine.[20] Maunoury’s force was also initially called the “Army of the Somme”. Advancing into the Santerre plain, Maunoury gave a good account of himself against von Kluck’s forces at Proyart on 29 August. The 14th Infantry Division, regulars redeployed from the east, blocked Linsingen’s columns advancing along the left bank of the Somme, using concentrated rifle and artillery fire. However, they were unable to block the Germans advancing from Peronne for long.[21]

By 1 September Sixth Army, as it was now called, included VII Corps (originally part of First Army) and V Corps (originally part of Third Army), as well as four reserve divisions, containing men from Lorraine, Auvergne, Brittany and the Charente. That day, with French forces falling back, Joffre vetoed Maunoury’s proposal to attack the Germans near Compiegne and instead ordered him to fall back, cover Paris and make contact with Gallieni, Military Governor.[22] [23]

Planning the Counterattack

In a handwritten note, responding to a request for information, Joffre recommended to Gallieni that “part of General Maunoury’s active forces” strike east against the German right wing. Joffre’s orders at this stage did not specify a date or time for the attack, although he did suggest that if the Germans continued to push south south east Maunoury might best operate on the north bank of the Marne. Von Kluck was probing into the gap between the BEF and French Fifth Army, a gap covered only by Conau’s cavalry corps.[24][25]

At 09:10 on 4 September Gallieni, following air reconnaissance reports and concerned that a continued French retreat would leave Paris uncovered and vulnerable to German attack, ordered Maunoury to be ready to strike east to take von Kluck in flank. Joffre, who was not consulted in advance but who had separately reached the same conclusion, approved the order, while still making up his mind about the timing of Fifth Army’s stand on the Marne. Gallieni also put Antoine Drude’s newly arrived Algerian 45h Infantry Division under Maunoury, raising Sixth Army to about 150,000 soldiers. Maunoury attended Gallieni’s three hour meeting with Murray (BEF Chief of Staff) on 4 September, which ended with their believing that the BEF would not join in any attack. [26][27][28]

Simultaneous negotiations were taking place between Wilson (BEF Sub Chief of Staff) and Franchet d’Esperey (the new commander of Fifth Army). At 10pm on 4 September, having heard that Franchet d’Esperey was ready to counter-attack, Joffre issued Instruction Generale No 6, fixing the date of the counter-attack for 7 September. As part of a general allied offensive, Maunoury was to cross the Ourcq in the direction of Chateau-Thierry. At Gallieni’s urging, Joffre brought the date of the attack forward to 6 September, as Maunoury would already be heavily engaged by then, a move which Joffre would later regret. [29][30]

Battle of the Ourcq: Maunoury attacks

Main article: First Battle of the Marne

Sixth Army marched out from Paris on the morning of 5 September.[31] Maunoury was to take up positions north-east of Meaux and was due to attack the next day along the north bank of the Marne. Instead fighting began at 13:00 on 5 September, in an area where French cavalry had encountered no Germans whilst scouting, but which had since been occupied by German IV Reserve Corps, whose commander decided to attack on his own initiative. During the night the Germans withdrew to the east, but von Kluck, commander of German First Army, shifted further forces up to face Maunoury’s Army. Kluck had II, IV, III and IX Corps south of the Marne.[32]

By 5 September Sixth Army consisted of 150,000 men: Frederic Vautier’s VII Corps, Henri de Lamaze's Fifth Group (55 and 56 Reserve Infantry Divisions), Charles Ebener’s Sixth Group (61 and 62 Infantry Divisions), Brigade Chasseur, Jean-Francois Sordet’s cavalry corps and Anthoine Drude’s 45th division. Together with the BEF, Maunoury had 191 battalions and 942 guns against von Kluck’s 128 battalions and 748 guns.[33]

Battle of the Ourcq: Germans redeploy

At 03:00 on 6 September Kluck ordered II Corps north, then at 16:30 IV Corps (a different unit to IV Reserve Corps). The following night (7/8 September) Kluck ordered the rest of his forces north, believing that a cavalry screen would be enough to hold back the “repeatedly beaten British”. Other than a brief advance on 6 September Maunoury’s Army struggled to defend its positions and on 8 September he drew his subordinate commanders’ attention to another line to which they could withdraw. Although Sixth Army had failed to envelop the German west flank as Joffre had hoped, Kluck’s redeployment had opened up a gap into which the BEF and French Fifth Army could advance. [34] [35]

Maunoury’s Army was reinforced by Victor Boelle’s IV Corps (formerly part of Third Army) on 7 September. [36] Maunoury enjoyed a numerical superiority of 32 infantry battalions and 2 cavalry divisions. 63 Reserve Infantry Division was broken by German bombardments and infantry charges, but the day was saved by Colonel Robert Nivelle, then commanding 5th Artillery Regiment of 45th Reserve Infantry Division, who first attracted attention to himself by having his 75mm guns fire directly onto the enemy. [37]

On the night of 7/8 September, Sordet, commander of the French cavalry, had joined Deprez’s 61st Infantry Division in falling back from the French left wing, instead of raiding into von Kluck’s rear at La Ferte-MIllon. Maunoury sacked Sordet.[38]

By time of the Battle of the Ourcq Maunoury had been strengthened by Trentinian’s 7th Infantry Division (formerly part of Fourth Army). Much of the division's infantry, artillery and staff of left Paris by train and truck on night of 7/8 September. Gallieni sent 103 and 104 Infantry Regiments (five battalions) by taxicab. Police commandeered 1200 black Renault cabs and shuttled 500 of them from Les Invalides west to Gagny, where each picked up 4 or 5 soldiers then drove to Nanteuil-les-Meaux overnight. The execution was less successful. Dimmed lights, and few maps, resulted in collisions and flared tempers. Some soldiers were forced to walk the final 2km to the front. [39][40]

For 8 September Joffre ordered Maunoury to “gain ground towards the north on the right bank of the Ourcq. Instead Maunoury aimed to retake the ground lost during the night and again attempt to outflank the German First Army. Herwig calls this “a poor decision”. Two assaults were beaten back by the Germans. It was very hot and food and water ran short. Late on the day, sensing von Kluck’s imminent counterattack, Gallieni urged Maunoury to hold his ground “with all your energy”. Maunoury informed Joffre that his “decimated and exhausted” troops were holding their positions. [41] By the evening of 8 September, Rudolf von Lepel’s brigade, marching southwest from Brussels, aimed to take Maunoury’s left flank. [42]

Battle of the Ourcq: Germans break off, Allies advance

By 9 September Lepel was engaging Maunoury’s left flank at Baron, northwest of Nanteuil-le-Haudoin. [43] During the fighting on the Ourcq and aware of the BEF advance from aviators’ reports, Lt-Col Hentsch of the German General Staff, concerned at the threat faced by Bulow's Second Army further south, ordered the battle broken off.[44][45] Von Kluck was not concerned about the BEF, which he thought could be held off by two German cavalry corps, and thought that German First Army was about to turn Maunoury’s left flank, and was dumbfounded to be ordered to retreat.[46][47]

On the evening of 9 September, with the Germans withdrawing and the BEF crossing the Marne, Joffre was not yet willing to announce victory and instead sent the War Minister a message praising Maunoury’s Sixth Army for defending Paris. Later that night he issued Instruction Particuliere No. 20 ordering a general advance. Sixth Army “resting its right on the Ourcq” was to try to envelop the Germans from the west. Eugene Bridoux’s V Cavalry Corps was set to play a key role. The BEF and Franchet d’Esperey’s Fifth Army were to push north from the Marne.[48][49]

Abandoning the plan to envelop the Germans from the west, Joffre now ordered all the French armies, including Sixth, to advance northeast. On 13 September Maunoury informed Joffre that Sixth Army, “which has not had a day of rest in about fifteen days, very much needs 24 hours rest”. Franchet and Foch (commander of the new Ninth Army) were saying similar things as the German line solidified north of the Aisne, although the French armies, along with the BEF, continued to attack until 18 September. [50]

Later War

Maunoury himself was severely wounded by being shot through the eye by a German sniper and rendered partially blind while touring the front on 11 March 1915, thereby ending his active career.[51]

Later Life

He died in 1923, and was posthumously promoted to Marshal of France.[52]

References

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 218

- ↑ Tuchman 1962, p344

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 241

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 218

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 218

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 218

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 241

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 218

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 241

- ↑ Tuchman 1962, p344

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 26

- ↑ Tuchman 1962, p263, 344

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 102

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 146

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 149–50

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p 78

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 29

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 177

- ↑ Philpott 2009, pp 18–19, 23

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 240, 311–12

- ↑ Philpott 2009, p 23

- ↑ Clayton 2003, pp 50–51

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p 82

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 227

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p 87

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 227

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 229

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp 88–89

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 229

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp 88–89

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 240–41

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp 92–93

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 231, 240–41

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp 92–93

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 54

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 226

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 247–48

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 261–62

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 262

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 56

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 262–63

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 277

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 265

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 56

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 274–75

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 56

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 281–82

- ↑ Herwig 2009, p 294

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p 96

- ↑ Herwig 2009, pp 304–05

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p 122

- ↑ Clayton 2003, p 218

References

- Brécard, Général C. T. (1937). Le Maréchal Maunoury 1847–1923 (in French). Paris: Editions Berger-Levrault. OCLC 12483293.

- Clayton, Anthony (2003). Paths of Glory. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35949-1.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02726-8.

- Evans, M. M. (2004). Battles of World War I. Select Editions. ISBN 1-84193-226-4.

- Herwig, Holger (2009). The Marne. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-7829-2.

- Klein, C. A. (1989). Maréchal Maunoury Le Soldat exemplaire, Hugues de Froberville (in French). Paris: Blois. ISBN 978-2-907659-02-4.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Tuchman, Barbara (1962). August 1914. Constable & Co. ISBN 978-0-333-30516-4.

|