Michał Kalecki

| |

| Born |

22 June 1899 Łódź, Congress Poland |

|---|---|

| Died |

18 April 1970 (aged 70) Warsaw, People's Republic of Poland |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Field | Macroeconomics |

School or tradition | Neo-Marxian economics/Post-Keynesian economics |

| Influences | Karl Marx (1885), Rosa Luxemburg (1913), Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky (1905) |

| Influenced | Nicholas Kaldor, Joan Robinson, Richard Kahn, Luigi Pasinetti, Alfred Eichner, John Eatwell, Josef Steindl, Piero Sraffa, Hyman Minsky, Marc Lavoie, Lance Taylor, Lawrence Klein,[1] Jan Kregel, John Maynard Keynes,[2] Athanasios Asimakopulos, Paul Sweezy, Paul A. Baran, Richard M. Goodwin, Robin Hahnel, Bill Mitchell, Jonathan Nitzan, Shimshon Bichler, Yanis Varoufakis |

| Contributions | The profit equation, Theories of mark-up and effective demand |

Michał Kalecki ([ˈmixau̯ kaˈlɛt͡ski]; 22 June 1899 – 18 April 1970) was a Polish economist. Over the course of his life, Kalecki worked at the London School of Economics, University of Cambridge, University of Oxford and Warsaw School of Economics as well as an economic advisor to governments of Cuba, Israel, Mexico and India. He also served as the deputy director of the United Nations Economic Department in New York City.

Kalecki has been called "one of the most distinguished economists of the 20th century." It is often claimed that he developed many of the same ideas as Keynes, before Keynes; however, since he published in Polish and French, he remains much less known to the English-speaking world. He offered a synthesis that integrated Marxist class analysis and the then-new literature on oligopoly theory, and his work had a significant influence on both Neo-Marxian (Monopoly Capital)[3] and Post Keynesian schools of economic thought. He was also one of the first macroeconomists to apply mathematical models and statistical data to economic questions.

In 1970, Michał Kalecki was nominated to the Nobel Prize in Economics, but died the same year.[4]

Biography

Early years: 1899–1932

Michal Kalecki was born in Łódź, Poland, on 22 June 1899. Information about his early years of life is very sparse, part of it being lost during the Nazi occupation. In 1917 Kalecki finished a Bachelor's degree, in order to join later the University of Warsaw, where he began civil engineering. He was a very clever student, and in this period he formalized a generalization of Pascal's theorem, concerning a hexagon drawn within a second degree curve. Kalecki generalized this for a polygon of 2n sides.

However, after his father had lost a small textile workshop, and though he obtained a job as an accountant, the young Kalecki had to search for another job in order to earn some money. During his first year in Warsaw he continued working sporadic jobs. After finishing his first year of engineering, he had to abandon his studies and from 1918 to 1921 he was in military service. Upon leaving the military he joined Gdańsk Polytechnic, staying there until 1924. Kalecki was then 25 years old.

During these years he first approached economics, although informally. He read mostly "unorthodox" works, particularly those of Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky and Rosa Luxemburg. Years later, this early influence of these two economists would be felt in some of his own writings related to the potential growth of a capitalist system.

In 1924 Kalecki was about to finish his studies when his father lost his job again. This forced him to leave the university again and this time permanently, because he needed to find a better paid job. His first job (which was also economic in nature) was to collect data on companies which asked for credit. In this same period he tried unsuccessfully to start a newspaper and then was forced to write articles for two economic newspapers, the Polska gospodarcza and Przeglad gospodarczy. It was probably in writing these articles that he began to acquire skills in obtaining and analyzing empirical information which was later included in his writings.

After five years and many articles he applied in 1929 for work at the Research Institute of Business Cycle and Prices (RIBCP). The experience he had acquired in the use of statistics got him the job. On 18 June 1930 he married Ada Szternfeld. In RIBCP he met Ludwig Landau, whose knowledge of statistics influenced the way that years later Kalecki presented the statistical part of his works. As a result his first works had a practical character particularly in establishing relationships between macro-magnitudes. In fact the first article that anticipated many subsequent contributions was published in 1932 in a magazine (which disappeared the same year) called Przeglad socjalistyczny (Socialist Review), under the pseudonym of Henryk Braun. The article dealt with the subject of the impact of wage cuts during an economic downturn. It was the first step towards the contributions he would make the following year.

The revolution of Kalecki and Keynes: 1933–1939

In 1933 Kalecki wrote an essay that brought together many of the issues which would dominate his thoughts for the rest of his life. This essay was Proba teorii koniunktury (An Essay on the Theory of the Business Cycle), which was published by the RIBCP and in which for the first time Kalecki was able to develop a comprehensive theory of business cycles. In October of the same year Kalecki read his essay to the International Econometrics Association and in 1935 published it in two major journals: Revue d’Economie Politique and Econometrica. Although the readers of both journals were not particularly impressed, Kalecki's article received favourable comments from such leading economists as Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen.

The following year he was granted a scholarship, which enabled him to travel to Sweden with his wife, where the followers of Knut Wicksell were trying to formalize a theory similar to Kalecki's. About that time he learnt of the publication of John Maynard Keynes's General Theory. This was most likely his motive for traveling to England. He first visited the London School of Economics and afterward went to Cambridge. Thus began his friendship with Richard Kahn, Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa, leaving an indelible mark on all of them. In 1937 he met Keynes. The meeting was cooler than expected, Keynes keeping aloof. Although the conclusions they had arrived at in their respective works were very similar, their characters could not have been more different. Kalecki very graciously neglected to mention that he enjoyed priority of publication. As Joan Robinson reminds us:

“Michal Kalecki’s claim to priority of publication is indisputable. With proper scholarly dignity (which, however, is unfortunately rather rare among scholars) he never mentioned this fact. And, indeed, except for the authors concerned, it is not particularly interesting to know who first got into print. The interesting thing is that two thinkers, from completely different political and intellectual starting points, should come to the same conclusion. For us in Cambridge it was a great comfort.”[5]

In 1939 Kalecki wrote one of his most important works, Essays in the Theory of Economic Fluctuations. Although his conception changed through the years, all the essential elements of Kaleckian economics were already present in this work: in a sense his subsequent work would consist of mere elaborations on ideas he had already propounded.

While Kalecki was generally enthusiastic about the Keynesian revolution, he predicted that it would not endure, in his article "Political Aspects of Full Employment", which Anatole Kaletsky has called one of the "most prescient economic paper ever published."[6] In the article Kalecki predicted that the full employment delivered by Keynesian policy would eventually lead to a more assertive working class and weakening of the social position of business leaders, causing the elite to use their political power to force the displacement of the Keynesian policy even though profits would be higher than under a laissez faire system: The erosion of social prestige and political power would be unacceptable to the elites despite higher profits.[6][7]

The war years: 1940–1945

In 1937 his friend Ludwig Landau was ejected from the RIBCP for political motives, which moved Kalecki to resign in protest and extend his stay abroad. But for this fortuitous fact, the war would have caught Kalecki in Poland and given his Jewish origins he would probably not have survived.

In any case, the Oxford Institute of Statistics (OIS) hired Kalecki in 1940. His job there consisted mainly of writing reports for the British Government concerning the management of the war economy. This did not prevent him from giving the occasional lecture at Oxford University. However, despite the elaborate reports prepared by Kalecki for the Government (most of them were concerned with the operation of the rationing of goods) the economists working for the Government often disregarded these reports. They did so, among other reasons, because many economists at the OIS were refugees. In the words of G. Feiwel: “As a consequence of this void in historical reporting, Kalecki's work of the war period is far less known than it deserves to be”.[8]

However, some of Kalecki’s major works were written during this period: in 1943 he wrote two articles, one of which dealt with new additions made to traditional business cycle theory. The second article presented Kalecki’s completely original theory of business cycles caused by political events. The latter was published in 1944 and was based on the premise of full employment. Actually that article was a compilation of studies by Kalecki and his colleagues at the OIS, who, however, were strongly influenced by Kalecki’s thinking.[9]

In 1945 Kalecki left the OIS, upset because he felt that his talents were not sufficiently appreciated. Kalecki displayed great modesty about his work and did not expect to be paid splendid tribute for his accomplishments. He was offended at being discriminated against on account of his immigrant status. In fact, one reason why he left the OIS and was not appointed to a more senior position was that he had not applied to become a British subject. (“Subject” was the term then used in Britain instead of “citizen”.)

The postwar years: 1945–1968

Leaving OIS, Kalecki went to París, where he stayed not long, moving to Montreal later, where he stayed fifteen months. In July 1946 he accepted the Polish government invitation to head the Central Planning Office of the Ministry of Economics, but he left some months later. At the end of 1946 he decided to move to New York. He liked the position offered him in the Economic Department of the United Nations Secretariat. He remained there until 1954, allowing him to develop his work as a political advisor. As in 1945, Kalecki resigned the position as a protest signal. It was argued instead that he was punished on political grounds (a non merited economic planner stance was attributed to him). In any case, the Senator Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunt depressed him as many of his closest friends were directly affected. In 1955 he returned to Poland and basically never went back to work abroad for any extended period.

When he arrived in Poland, Kalecki was quite hopeful with the ability to make reforms that were socially advantageous. In 1957 he was appointed chairman of the Committee for the Perspective Plan. The plan had a horizon covering 1961 to 1975, and was basically a practical level embodiment of Kalecki's theories of growth in socialist economies. However, final plan developed by Kalecki was dismissed by board members as too gloomy and tinged as defeatist. Then things got worse, as related by G. Feiwel:

“By 1959 the policy makers had forsaken rationality altogether and had reverted to "hurrah planning". Constraints on the growth rate were disregarded under the spell of optimism engendered by the good performance in 1956–57. Although Kalecki remained with the Commission of the Perspective Plan for another year beyond 1959, all concerned knew that it was a pro forma function. The end of 1958 had marked the beginning of the erosion of his influence.”[10]— G.Feiwel (1975)

Thereafter, Kalecki spent much time of the rest of his life in teaching and research. There were however issues that he had neglected during his time at the Commission. In 1959 he began directing a seminar on the socio-economic problems of the Third World along with Oskar Lange and Czesław Bobrowski. For him the problem was not new, having already written outstanding articles dealing with these issues thoroughly, especially those related to development.

He also devoted this period to the study of mathematics. In fact, this was in part a continuation of the interest he had when he was young and generalized Pascal’s theorem. The investigations were in number theory and probability. For him these periods of time dedicated to mathematics were a release of extreme disappointment caused by the lack of power to help his country in economic policy.

Later years 1968–1970

John Maynard Keynes had said years before that knowledge of the laws governing the capitalist economy would make people more prosperous, happy and more responsible respect the economic decisions taken. However, Kalecki contested this view, arguing that in fact the idea of political business cycle (governments can force situations to their advantages) seems to point in the opposite direction. As he grew older, Kalecki was ever more convinced of this, showing an increasingly pessimistic view of humanity.

Michal Kalecki died on 4 April 1970 at the age of 70 years, and although he was bitterly disappointed with all political developments, he lived long enough to see recognition of the value of his many original contributions to economics. In his last visit to Cambridge he gave a conference where he was greatly applauded for the clearness of his explanation as well as by the trajectory of his life. Probably one of the most moving paragraphs concerning the end of his life we owe Feiwel, an excellent summary of the life of this remarkable man:

“With Michal Kalecki's death, the world lost a unique individual of extremely high principles, powerful energy, and brilliant mind, and economics lost a model and inspiration. His legacy, however, cannot be erased. […] He demanded perfection, or at least an unalloyed commitment to that goal, he could not tolerate slovenly thought or superficial minds, and, most significant, he simply would not compromise his principles. Looking back over his troubled years, Kalecki once made the sad but true observation that the story of his life could be compressed into a series of resignations in protest-against tyranny, prejudice, and oppression.”[11]

Theoretical contributions

The profit equation

The volume of economic literature written by Kalecki during his life was very large. Although in most of his articles he returned to the same subjects (business cycles, determinants of investment or socialist planning), he often did it from a slightly unusual perspective and with original contributions.

Kalecki's most famous contribution is his profit equation. Kalecki, whose early influences always came from Marxian economists,[12] thought that the volume and profit sharing in a capitalist society were vital points to be treated. This followed from Marx's work on certain relationships such as the rate of surplus value or the organic composition of capital (and even a forecast about the overall trend of profits). However, Marx was never able to make any meaningful statement about the total volume of profits in a given period.

Kalecki derived this relationship in an extremely concise, elegant and intuitive way. He starts by making simplifications which he later progressively eliminates. These assumptions are:

- Divide the whole economy into two groups: workers, who earn only wages and capitalists, who earns only profits.

- Workers do not save.

- The economy is closed (there is no international trade) and there is no public sector.

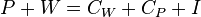

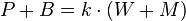

With these assumptions Kalecki derives the following accounting identity:

where  is the volume of gross profits (profits plus depreciation),

is the volume of gross profits (profits plus depreciation),  is the volume of total wages,

is the volume of total wages,  is capitalists consumption,

is capitalists consumption,  is workers consumption and

is workers consumption and  is the gross investment that have been made in the economy. Since we have supposed workers who do not save (that is, to say

is the gross investment that have been made in the economy. Since we have supposed workers who do not save (that is, to say  in the preceding equation), we can simplify the two terms and arrive at:

in the preceding equation), we can simplify the two terms and arrive at:

This is the famous profits equation, which says that profits are equal to the sum of investment and capitalist’s consumption.

At this point, Kalecki goes on to determine the causal link between the two sides of the equation: Does capitalist’s consumption and investment determine profits or profits instead determine capitalist consumption and investment? In answer to this, Kalecki says

“The answer to this question depends on which of these items is directly subject to the decisions of capitalists. Now, it is clear that capitalists may decide to consume and to invest more in a given period than in the preceding one, but they cannot decide to earn more. It is, therefore, their investment and consumption decisions which determine profits, and not vice versa”.[13]

For someone who has not seen before the preceding relationship, it might after a rigorous examination seem somewhat paradoxical. If the capitalists consume more, obviously the amount of funds which they have at the end of the year should be less. However, this reasoning, obvious to the individual entrepreneur, is not true for the business class as a whole, as the consumption of one capitalist becomes part of the profits of another. In a way, they are masters of their fate.[14]

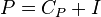

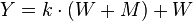

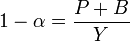

On the other hand, we should point out that if in the preceding equation we move capitalist consumption to the left, the equation becomes:

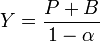

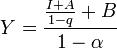

Since profits minus capitalist’s consumption are the total saving in the economy because the workers do not save. The previous causal relationship still applies, and goes from investment to saving. That is to say, total savings are determined once investment has been determined. So, in some way, investment generates sufficient resources. Investment finances itself,[15] so that equality between savings and investment is not caused by any interest rate mechanism as earlier economists thought. Finally, we can eliminate the assumptions of the original equation: the economy can be open, there may be a government sector and we can let workers save something. The resulting equation is:

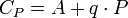

In this model total profits (net taxes this time) are the sum of capitalist consumption, investment, public deficit, net external surplus (exports minus imports) minus workers savings. Before trying to explain income distribution, Kalecki introduces some behavioural assumptions in his simplified equation of profits. For him, investment is determined by a combination of many factors difficult to explain, which are considered given, exogenous. Regarding capitalist consumption, he considers that a simplified form is the following equation:

That is, capitalist consumption depends on a fixed part (independent part), the term  , and a proportional share of profits, the term

, and a proportional share of profits, the term  , which is called the marginal propensity to consume of the capitalists. If this consumption function is substituted into the profit equation, we have:

, which is called the marginal propensity to consume of the capitalists. If this consumption function is substituted into the profit equation, we have:

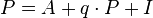

And, if we finally express in terms of  , this give us:

, this give us:

The advantage of this manipulation is that we have reduced the two earnings determinants (capitalist’s consumption and investment) to only one (investment).

Income distribution and the constancy of the share of wages

Income distribution is the other pillar of Kalecki’s efforts to build a business cycle theory. To do this, Kalecki assumes that the industries compete in imperfectly competitive markets, more particularly in oligopolistic markets where the firms set a mark-up on its variable average costs (raw materials, wages of employees on the shop floor that are supposed to be variable) in order to cover their overhead costs (salaries to senior management and administration) to obtain a certain amount of profit. The mark-up fixed by firms is higher or lower depending on the degree of monopoly, or the ease with which firms raise the price without seeing reduced the quantity demanded. This can be summarized in the next equation:

where  and

and  are respectively again profits and wages,

are respectively again profits and wages,  is the average mark-up for the whole economy,

is the average mark-up for the whole economy,  is the cost of raw materials and

is the cost of raw materials and  is the total amount of salaries (which must be distinguished from wages, since these are variables and salaries are considered fixed).

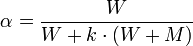

The preceding equation allows us to derive the wage share in the national income. If we add to both members

is the total amount of salaries (which must be distinguished from wages, since these are variables and salaries are considered fixed).

The preceding equation allows us to derive the wage share in the national income. If we add to both members  , and pass one to the other side, we have:

, and pass one to the other side, we have:

If we multiply each side by  , and we pass to the other term, we have:

, and we pass to the other term, we have:

or, which is the same:

where  is the wage share in the national income and

is the wage share in the national income and  is the relation between the cost of raw materials and wages. It follows that the wage share in the national income depends negatively on mark-up and on the relationship of raw material costs to wages.

At this point Kalecki’s interest is in finding out what’s happen to the wage share during the business cycle. During recessions, firms collaborate among themselves to cope with the fall of profits, so the degree of monopoly increases and this increases the mark-up. The

is the relation between the cost of raw materials and wages. It follows that the wage share in the national income depends negatively on mark-up and on the relationship of raw material costs to wages.

At this point Kalecki’s interest is in finding out what’s happen to the wage share during the business cycle. During recessions, firms collaborate among themselves to cope with the fall of profits, so the degree of monopoly increases and this increases the mark-up. The  parameter goes up. Nonetheless, the lack of demand during recessions causes a fall in the price of raw materials, so the

parameter goes up. Nonetheless, the lack of demand during recessions causes a fall in the price of raw materials, so the  parameter goes down. The argument is symmetrical during the boom: prices of raw materials rise (

parameter goes down. The argument is symmetrical during the boom: prices of raw materials rise ( parameter increases) meanwhile the strength of unions due to increased occupation of labour causes the degree of monopoly to fall and thereby the mark-up level. We conclude therefore that α parameter is roughly constant over the business cycle.

parameter increases) meanwhile the strength of unions due to increased occupation of labour causes the degree of monopoly to fall and thereby the mark-up level. We conclude therefore that α parameter is roughly constant over the business cycle.

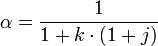

Finally, we need an equation that determines the total product of an economy. We can state that:

that is simply to say that the share of profits and salaries are the complement of the share of wages. Solving for we have:

we have:

Now we have the three components necessary to determine total product: an equation of profits, a theory of income distribution and an equation that links the product with profits and income distribution. Now it only remains to substitute the equation of  which we obtained before:

which we obtained before:

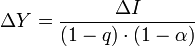

The preceding equation finally shows the determination of income in a closed system without public sector. It shows that output is completely determined by investment. How will output change from one period to the next? Insofar we have assumed that  and

and  are constants, the above formula comes down to the multiplier:

are constants, the above formula comes down to the multiplier:

That is to say, the problem of the change in output and hence the business cycle it is due to changes in the volume of investment. Therefore it is in investment where we must find the reasons for the fluctuations of a capitalist economy.

Determinants of investment

All this allows us to see the crucial role played by investment in a capitalist system. If we can find an investment function which somehow was well specified, then surely we could resolve many problems of the capitalist economy. This subject was treated for a long time by Kalecki, and he was never completely satisfied with his solutions. This is because the factors that determine the investment decisions are multiple and not always clear. A thorough analysis of this subject would be intolerably long, so the best way to continue is to introduce the solution that Kalecki gave in one of his books.

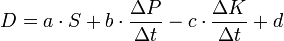

Kalecki’s investment function in the study of business cycles is the following:

where  is the amount of investment decisions in fixed capital,

is the amount of investment decisions in fixed capital,  ,

,  and

and  are parameters that specify a linear relation,

are parameters that specify a linear relation,  is a constant which can vary in the long-run,

is a constant which can vary in the long-run,  are profits,

are profits,  is the gross saving generated by the firm, and

is the gross saving generated by the firm, and  is the stock of fixed capital.

The previous equation shows that investment decisions depend positively on the savings generated by the firm, on the rate of change of profits and a constant subject to long-term changes, and negatively on the increase of fixed capital.

is the stock of fixed capital.

The previous equation shows that investment decisions depend positively on the savings generated by the firm, on the rate of change of profits and a constant subject to long-term changes, and negatively on the increase of fixed capital.

We can see that the above equation is able to generate cycles by itself. During booms, firms are able to generate more cash-flow and enjoy increases in profits. However, the increase in orders for capital investment increases the stock of capital, until it proves unprofitable to make more investments. Ultimately, the variations in the level of investment generate the business cycles. As Kalecki would say later:

“The tragedy of investment is that it causes crisis because it is useful. Doubtless many people will consider this paradoxical. But it is not the theory which is paradoxical, but its subject –the capitalist economy.”[16]

Influence

In the first half of the 1990s, Oxford University Press published 7 volumes of the Collected Works of Michal Kalecki, referring to him as "one of the most distinguished economists of the 20th century." Many of his works were translated into English for the first time in this collection.

Kalecki's work would inspire the Cambridge (UK) Post-Keynesians, especially Joan Robinson, Kaldor and Goodwin, as well as modern American Post Keynesian economics.[17]

Publications

In Polish

- Próba teorii koniunktury (1933)

- Szacunek dochodu społecznego w roku 1929 (1934, z Ludwikiem Landauem)

- Dochód społeczny w roku 1933 i podstawy badań periodycznych nad zmianami dochodu (1935, z Landauem)

- Teoría cyklu koniunkturalnego (1935)

- Płace nominalne i realne (1939)

- Teoría dynamiki gospodarczej (1958)

- Zagadnienia finansowania rozwoju ekonomicznego (1959, w: Problemy wzrostu ekonomicznych krajów słabo rozwiniętych pod redakcją Ignacego Sachsa i Jerzego Zdanowicza)

- Uogólnienie wzoru efektywności inwestycji (1959, z Mieczysławem Rakowskim)

- Polityczne aspekty pełnego zatrudnienia (1961)

- O podstawowych zasadach planowania wieloletniego (1963)

- Zarys teorii wzrostu gospodarki socjalistycznej (1963)

- Model ekonomiczny a materialistyczne pojmowanie dziejów (1964)

- Dzieła (1979–1980, 2 tomy)

In English

- "Mr Keynes's Predictions", 1932, Przegląd Socjalistyczny.

- An Essay on the Theory of the Business Cycle (Próba teorii koniunktury), 1933.

- "On foreign trade and domestic exports", 1933, Ekonomista.

- "Essai d'une theorie du mouvement cyclique des affaires", 1935, Revue d'economie politique.

- "A Macrodynamic Theory of Business Cycles", 1935, Econometrica.

- "The Mechanism of Business Upswing" (El mecanismo del auge económico), 1935, Polska Gospodarcza.

- "Business upswing and the balance of payments" (El auge económico y la balanza de pagos), 1935, Polska Gospodarcza.

- "Some Remarks on Keynes's Theory", 1936, Ekonomista.

- "A Theory of the Business Cycle", 1937, Review of Economic Studies.

- "A Theory of Commodity, Income and Capital Taxation", 1937, Economic Journal.

- "The Principle of Increasing Risk", 1937, Económica.

- "The Determinants of Distribution of the National Income", 1938, Econometrica.

- Essays in the Theory of Economic Fluctuations, 1939.

- "A Theory of Profits", 1942, Economic Journal.

- Studies in Economic Dynamics, 1943.

- "Political Aspects of Full Employment", 1943, Political Quarterly.

- Economic Implications of the Beveridge Plan (1943)

- "Professor Pigou on the Classical Stationary State", 1944, Economic Journal.

- "Three Ways to Full Employment", 1944 in Economics of Full Employment.

- "On the Gibrat Distribution", 1945, Econometrica.

- "A Note on Long Run Unemployment", 1950, Review of Economic Studies.

- Theory of Economic Dynamics: An essay on cyclical and long-run changes in capitalist economy, 1954. 1965 reprint.

- "Observations on the Theory of Growth", 1962, Economic Journal.

- Studies in the Theory of Business Cycles, 1933–1939, 1966.

- "The Problem of Effective Demand with Tugan-Baranovski and Rosa Luxemburg", 1967, Ekonomista.

- "The Marxian Equations of Reproduction and Modern Economics", 1968, Social Science Information.

- "Trend and the Business Cycle", 1968, Economic Journal.

- "Class Struggle and the Distribution of National Income" (Lucha de clases y distribución del ingreso), 1971, Kyklos.

- Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, 1933–1970, 1971.

- Selected Essays on the Economic Growth of the Socialist and the Mixed Economy, 1972.

- The Last Phase in the Transformation of Capitalism, 1972.

- Essays on Developing Economies, 1976.

- Collected Works of Michał Kalecki (seven volumes..), Oxford University Press, 1990–1997.

In Spanish

- Teoría de la dinámica económica: ensayo sobre los movimientos cíclicos y a largo plazo de la economía capitalista, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1956

- El Desarrollo de la Economía Socialista, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1968

- Estudios sobre la Teoría de los Ciclos Económicos, Ariel, 1970

- Economía socialista y mixta: selección de ensayos sobre crecimiento económico, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1976

- Ensayos escogidos sobre dinámica de la economía capitalista 1933–1970, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1977

- Ensayos sobre las economías en vías de desarrollo, Crítica, 1980

See also

References

- ↑ Don Patinkin, Anticipations of the General Theory?: And Other Essays on Keynes, University of Chicago Press, 1984, p. 61.

- ↑ Bill Mitchell (August 13, 2010), "Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment": "... those scholars who do not see Keynes as being the central figure in the development of the theory of effective demand [...] lean to the view that the transition from the Treatise (1930) to the General Theory (1936) was so great that it is likely that Keynes knew what Kalecki had written and published and was influenced by it."

- ↑ Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler. Capital as power: a study of order and creorder. Taylor & Francis, 2009, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Ivan Figura (October 2005). "PROFILES OF WORLD ECONOMISTS: MICHAL KALECKI" (PDF). BIATEC – odborný bankový časopis XIII: 21–25.

- ↑ Robinson, Joan (1966). "Kalecki and Keynes". Problems of Economic Dynamics and Planning: Essays in Honour of Michal Kalecki. Polish Scientific Publishers. p. 337.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Anatole Kaletsky (2011). Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy. Bloomsbury. pp. 52–53, 173, 262. ISBN 978-1-4088-0973-0.

- ↑ Kalecki (1943). "Political Aspects of Full Employment". Monthly Review. The Political Quarterly. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ George R. Feiwel (1975). p. 239.

- ↑ Confianza, Reformas y Crisis Económica

- ↑ George R. Feiwel (1975). p. 297.

- ↑ George Feiwel: 1975, p. 455.

- ↑ Alessandro Roncaglia, The wealth of ideas: a history of economic thought, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 411.

- ↑ Michal Kalecki (1971), pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Maurice Dobb (1973), p. 223.

- ↑ Michal Kalecki (1971), p. 84.

- ↑ Dobb (1973), p. 222

- ↑ "Michal Kalecki, 1899–1970". Profiles. The History of Economic Thought. The New School. Retrieved 12 March 2009. http://www.hetwebsite.org/het/profiles/kalecki.htm

Sources

- Dobb, Maurice (1973). Theories of value and distribution since Adam Smith. Cambridge University Press.

- Feiwel, George R. (1975). The Intellectual Capital of Michal Kalecki: A Study in Economic Theory and Policy. Fondo de Cultura Económica, México.

- Kalecki, M. (2009) Theory of Economic Dynamics: An Essay on Cyclical and Long-Run Changes in Capitalist Economy, Monthly Review Press

- Kalecki, M. Collected Works of Michal Kalecki, Oxford University Press, USA.

- Kalecki, M. (1971) Selected essays on the dynamics of the capitalist economy, Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Sadowski, Zdzislaw L.; Szeworski, Adam (2004). Kalecki's Economics Today. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29993-4.

- King, J. E. (2003). "An economist from Poland". A History of Post Keynesian Economics Since 1936. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. pp. 35–55. ISBN 1-84376-650-7.

- Kriesler, Peter (1997). "Keynes, Kalecki and The General Theory". In Harcourt, Geoffrey Colin; Riach R. A.; Riach, P. A. (ed.). A "Second Edition" of the General Theory. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14943-6.

- Vianello, F. [1989], “Effective Demand and the Rate of Profits: Some Thoughts on Marx, Kalecki and Sraffa”, in: Sebastiani, M. (ed.), Kalecki's Relevance Today, London, Macmillan, ISBN 978-03-12-02411-6.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Michał Kalecki |

- Biography

- Kalecki Distribution Cycle

- Peter Kriesler's Keynes, Kalecki and the General Theory"

- Peter Kriesler's "Microfoundations: A Kaleckian perspective"

- Malcolm Sawyer's "The Kaleckian Analysis and the New Mellium"

- Review (by Gary Dymski) of Sebastiani's book, Kalecki and Unemployment Equilibrium in JEL

- Alberto Chilosi "Kalecki's Theory of Income Determination: A Reconstruction and an Assessment"

- Julio López G. and Michaël Assous"Michal Kalecki"

- Theory of Economic Dynamics – Monthly Review

- Kalecki’s pricing and distribution theory F.M. Rugitsky

|