Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory or "Met Lab" was the code name for part of the World War II–era Manhattan Project - the U.S. program to develop the atomic bomb. It was headed by Arthur H. Compton, a Nobel Prize laureate and Professor of Physics at the University of Chicago. The Lab produced the first controlled nuclear chain reaction in Chicago Pile-1, built at the University's old football stadium, Stagg Field.

History

In July 1939, at the urging of nuclear physicists Eugene Wigner and Leó Szilárd, Albert Einstein sent a letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, explaining the military potential of nuclear fission and calling for the United States to develop atomic weapons before Nazi Germany.

In response, Roosevelt appointed a committee to direct the research. Early funding was meager, but in 1940, scientists at Columbia University and the University of California demonstrated the weapons potential of the isotope uranium-235 and the newly discovered element plutonium.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, development of the atomic bomb became urgent. Compton proposed consolidation of atomic research at University of Chicago, and also an ambitious schedule that called for producing the first atomic bomb in January 1945, a goal that was missed by only six months. Both proposals were adopted.

Compton's new operation was given the "cover" name of the "Metallurgical Laboratory". The Lab's tasks were to produce chain-reacting "piles" of uranium to convert to plutonium, find ways to separate the plutonium from the uranium, and to design a bomb. Most of the Lab's offices were in the University's Eckhart Hall; Szilard later wrote that "the morale of the scientists could almost be plotted in a graph by counting the number of lights burning after dinner in the offices at Eckhart Hall."[1][2]

The notable scientists assembled at the Lab included, besides Compton and Szilard, another Nobel laureate, Enrico Fermi, and future laureates Wigner and Glenn T. Seaborg.

In August 1942, Seaborg's team chemically isolated the first weighable amount of plutonium from uranium irradiated in cyclotrons.

Fermi worked on the design and construction of a "pile" of uranium and graphite that could be brought to critical mass in a controlled, self-sustaining nuclear reaction.

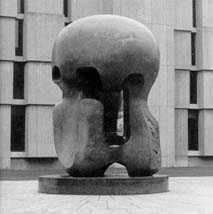

Fermi's team built Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) at the University's abandoned football stadium. They demonstrated it on 2 December 1942. (It was the world's first "nuclear reactor," although that term was not used until 1952.) The location is commemorated as the Site of the First Self-Sustaining Nuclear Reaction, a National Historic Landmark, featuring a sculpture by Henry Moore.

Later activities

Once the Lab had demonstrated the key elements of the atomic bomb, it was now necessary to implement the Lab's discoveries on an industrial scale, and to build and test the bomb.

This further work was done at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Hanford, Washington, and Los Alamos, New Mexico. Many of the top scientists left the Lab for these other sites.

In 1943, CP-1 was dismantled, and rebuilt as CP-2, in Red Gate Woods, a forest preserve outside the city. Because of the location, the site was code-named "Argonne", after the Forest of Argonne in France, where U.S. troops fought in World War I.

The Lab continued to do important atomic research, both on the campus of the University and at "Argonne", which became the Lab's primary site. On 1 July 1946, the Lab became Argonne National Laboratory.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Richard Melzer (1999). How the Secret of the Atomic Bomb was Stolen During World War II. Sunstone Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-86534-304-7.

- ↑ http://www.anl.gov/about-argonne/history

External links

- The First Pile by Corbin Allardice and Edward R. Trapnell

- Manhattan Project Signature Facilities

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory Review

- Chicago Pile 1 Pioneers

- The First Pile

- The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||