Messiria tribe

The Messiria known also under the name of Misseriya Arabs are a branch of the Baggara Arabs tribes.[1] Their language is the Chadic Arabic. Numbering over one million, the Baggara are the second largest people group in Western Sudan, extending into Eastern Chad. They are primarily nomadic cattle herders and their journeys are dependent upon the seasons of the year. The use of the term Baggara carries negative connotations as slave raiders, so they prefer to be called instead Messiria.

Geography of Messiria Country (Dar Al Messiria)

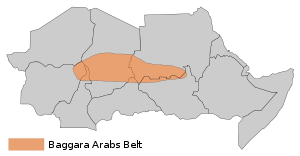

The term Dar means land or location. The word Al or al and sometimes El or el corresponds to the definite article The in English. The term Dar Al Messiria means the land or location of the Messiria. According to Ian Cunnison 1966,[2] the Arab nomads of the Sudan and Chad republics are of two kinds: camelmen (called Abbala) and cattlemen (called Baggara). the Term Baggara means simply cowman but the Sudanese apply the word particularly to the nomadic cattlemen, who span the belt of savanna between Lake Chad and the White Nile. This belt is the homeland for the Baggara people for centuries. Ian Cunnison, referenced above said "History and environment together throw light on their distribution". In Sudan, while the Abbala lives on the semi-desert part of the region: northern Kordofan and Darfur, the Baggara on the other hand lives on their southern fringes; occupying the area roughly south of 12 degree north and extending well into flood basins of the White Nile to the south.

In general the Dar Al Messiria or their zones can be divided into three areas:

1.1. Dar Al Messiria in Kordofan, Sudan.

1.2. Dar Al Messiria in Darfur, Sudan.

1.3. Dar Al Messiria in Chad.

The Messiria in the three different zones are separated for long times to the point that they have developed localized cultural and social differences. The Messiria in Kordofan know little if any about the Messiria in Dar Fur and Chad, but they belong to the same tribe and they have similar subtribal divisions and diversities.

Dar Al Messiria in Kordofan, Sudan

In Kordofan, the Messiria occupies the area historically known as West Kordofan, among their well known locations are: Abyei, Babanousa, El Muglad, Lagawa, El Mairam, and Lake Kailak.

Messiria Divisions in Kordofan

The main divisions of Messiria in Kordofan are Messiria Zurug; literally the name means The dark ones and Messiria Humr; means The red ones. These names: Zurug and Humr do not mean in any way that the Zurug are darker in skin color than Humr, but most likely the Humr are darker than Zurug ones. According to MacMichael, 1967:[3] The two divisions have become so distinct that the Humr have ceased to rate themselves Messiria. However, in Sudan today, still they are called Messiria Humr and Messiria Zurug and still they acknowledge their common history and ancestry.

- Messiria Zurug – According to MacMichael, 1967[3] the Messiria Zurug have the following divisions:

Still there subtribal divisions with each subtribes.

- Messiria Humr – According to Ian Cunnison, 1966:[2] The Humr are divided into:

Dar Al Messiria in Darfur, Sudan

The area known as Nitega (نتيقة) is the mainland of the Messiria in Dar Fur, among the landmarks in the area is the Mountain Karou (جبل كرو).

Second Sudanese Civil War: 1983–2005

Background of the conflict

The Misseriyya mostly live around Kordofan and migrate south into the Dinka territory. They are marginally represented in Darfur and there they live a semi-sedentary life. The Misseriyya were once a larger group, but overtime it fractured into smaller groups.[4]

The location of Messiria of Kordofan is at the border zone between Sudan and Southern Sudan, specially the southern Fringes of their nomadic zone. The Abyei area is claimed by Messira as well as by Ngok Dinka, to be theirs. While the Messiria are Baggara Arabs, Sunni Muslims and identified as Northerners, on the other hand, Ngok Dinka are Southerners and identified as Africans either Christians or Animists. The Messiria historians tell that, one of their grand parents named sheikh Abu Nafisa his burial is found far southern of present Abyei town and he had died around the early 1770s. Henderson, MacMichael and Ian Cunnison all attest the presence of Messiria in the eighteenth century. Similar history is also available for the nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms on the same area. Being both nomads, The Messiria and Dinka coexisted for long time and shared the grazing resources. Those Messiria who have most contact with Ngok Dinka are the Messiria Humr. The Messiria Zurug share most of their land with the Nuba tribes, along the western sides of the national highway connecting Deling city to Kadugli; the capital city of South Kordofan and extending to Talodi city. On the eastern side of this national highway found the Hawazma tribes sharing the land also with the Nuba tribes. The Nuba are indigenous Africans inhabiting the area known as Nuba Mountains of Southern Kordofan and mostly Sunni Muslims. Both Nuba and Dinka are sided with Southern Rebels (SPLA/SPLM) during the civil war, while Messiria and Hawazma sided with Sudanese Government.

Historical grazing disputes

During the dry season the Misseriya migrate to the river Kiir in Abyei. They call the region the Bahr Al Arab.[5]

Both branches of Messiria, the Humr and the Zurug, are involved in historical grazing disputes and isolated fights along their southern borders, either with Dinka, Nuer or Nuba over grazing and water resources. The traditional fighting was intensified during the first Southern guerrilla’s fighting, called Anyanya I, in 1964 when a whole Messiria nomad camp around lake Abyyad was massacred in a terrible human slaughter by Anyanya fighters, none were spared including children, elderly and brides; many Messiria were abducted and women were raped by the rebels. The Messiria retaliated with a sequence of attacks targeting Southern villages and nomadic camps; they abducted children and raided cattle. At the time, the abductions and retaliations became the norm in the region, but, mostly children and cattle were retrieved by local authorities and the spirit and will of coexistence always prevailed.

Such targeting of Anyanya fighters on Messiria nomads lead to Messiria starting to accumulate weaponry to counterbalance the rebel fighters' force. Earlier incidents in the early eighteenth century during British rule, had led to both Hawazma and Messiria taking up arms. In around 1908, the British armed the Nuba to fight against the expansion of the Northern Arabs in the region. Weapons, known locally as Marmatoun and Ab’gikra, were as common among Nuba as AK-47 among Baggara Arabs today. All these indicate that the ingredients of ethnic war already exist in the region and the new SPLA war was just an ignition of an existing ethnic chasm in the area.

In Abyei the Dinka Ngok and Misseryia are engaged in territorial disputes.[6]

The Civil War

See the Civil War under Hawazma. The Messiria are the first Northern tribes and the first Baggara tribes to suffer from the Southern war.

The Sudanese government gave the Misseriya Arab militia machine guns and ordered them to drive the Nilotic peoples from the Western Upper Nile oil region. They successfully took the Luk Nuer in Bentiu and Eastern Jikany Nuer in 1984.[7]

References

- ↑ Adam, Biraima M. 2012. Baggara of Sudan: Culture and Environment, Amazon online Books. Baggara of Sudan: Culture and Environment

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ian Cunnison, 1966, Baggara Arabs, Power and the lineage in a Sudanese Nomad Tribe, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pages: 1–3

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Harold Alfred MacMichael, 1967, The Tribes of Northern and Central Kordofán, Published by Cass, ISBN 0-7146-1113-1, ISBN 978-0-7146-1113-6, 260 pages.

- ↑ Flint, J. and Alex de Waal, 2008 (2nd Edn), Darfur: A new History of a Long War, Zed Books.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch (Organization) (2008). Abandoning Abyei: destruction and displacement, May 2008. Human Rights Watch. p. 12. ISBN 1-56432-364-1. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ↑ Al Jazeera (5 Jan 2011). "Tribal trouble in Sudan". ALJAZEERA. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ Jemera Rone, Human Rights Watch (Organization) (1999). Famine in Sudan, 1998: the human rights causes. Human Rights Watch. p. 140. ISBN 1-56432-193-2. Retrieved 9 January 2011.