Mesopropithecus

| Mesopropithecus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mesopropithecus globiceps skull | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | †Palaeopropithecidae |

| Genus: | †Mesopropithecus Standing, 1905[2] |

| Species[3] | |

| |

| |

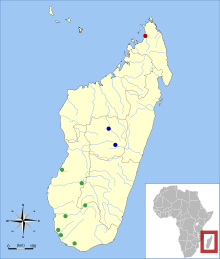

| Subfossil sites for Mesopropithecus[3] red = M. dolichobrachion; green = M. globiceps; blue = M. pithecoides | |

| Synonyms[2][4] | |

|

Neopropithecus Lamberton, 1936 | |

Mesopropithecus is an extinct genus of small to medium-sized lemur, or strepsirrhine primate, from Madagascar that includes three species, M. dolichobrachion, M. globiceps, and M. pithecoides. Together with Palaeopropithecus, Archaeoindris, and Babakotia, it is part of the sloth lemur family (Palaeopropithecidae). Once thought to be an indriid because its skull is similar to that of living sifakas, a recently discovered postcranial skeleton shows Mesopropithecus had longer forelimbs than hindlimbs—a distinctive trait shared by sloth lemurs but not by indriids. However, as it had the shortest forelimbs of all sloth lemurs, it is thought that Mesopropithecus was more quadrupedal and did not use suspension as much as the other sloth lemurs.

All three species ate leaves, fruits, and seeds, but the proportions were different. M. pithecoides was primarily a leaf-eater (folivores), but also ate fruit and occasionally seeds. M. globiceps ate a mix of fruits and leaves, as well as a larger quantity of seeds than M. pithecoides. M. dolichobrachion also consumed a mixed diet of fruits and leaves, but analysis of its teeth suggests that it was more of a seed predator than the other two species.

Although rare, the three species were widely distributed across the island yet allopatric to each other, with M. dolichobrachion in the north, M. pithecoides in the south and west, and M. globiceps in the center of the island. M. dolichobrachion was the most distinct of the three species due to its longer arms. Mesopropithecus was one of the smallest of the extinct subfossil lemurs, but was still slightly larger than the largest living lemurs. Known only from subfossil remains, it died out after the arrival of humans on the island, probably due to hunting pressure and habitat destruction.

Classification and phylogeny

Mesopropithecus is a genus within the sloth lemur family (Palaeopropithecidae), which includes three other genera: Palaeopropithecus, Archaeoindris, and Babakotia. This family in turn belongs to the infraorder Lemuriformes, which includes all the Malagasy lemurs.[2]

Mesopropithecus was named in 1905 by Herbert F. Standing using four skulls found at Ampasambazimba. He noted that the animal had characteristics of both Palaeopropithecus and the living sifakas (Propithecus).[5] In 1936, Charles Lamberton defined Neopropithecus globiceps (based on one skull from Tsirave) and N. platyfrons (based on two skulls from Anavoha). He thought that Neopropithecus was a separate, intermediate genus between Mesopropithecus and Propithecus. In 1971, paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall merged N. platyfrons into N. globiceps and Neopropithecus into Mesopropithecus.[3]

Until 1986, Mesopropithecus was only known from cranial (skull) remains from central and southern Madagascar, and because these are similar to teeth and skulls of living indriids, particularly those of Verreaux's Sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi), Mesopropithecus was often assigned to the family Indriidae.[2][6][7] For example, in 1974, Tattersall and Schwartz labeled Mesopropithecus as a sister group to sifakas.[1][3] With the discovery of an associated skeleton of M. dolichobrachion near Ankarana in 1986, it became clear that Mesopropithecus shared distinct traits with sloth lemurs.[1][6][8][9] Unlike the indriids, but like the sloth lemurs, they had elongated forelimbs and other adaptations for arboreal suspension (hanging in trees), linking them most closely to family Paleaeopropithecidae.[2] A comparison of these morphological traits between the sloth lemurs and indriids suggest that Mesopropithecus was the first genus to diverge within the sloth lemur family.[1]

Species

Three species are recognized within Mesopropithecus:[3]

- M. pithecoides, described in 1905, was the first species to be formally named.[2] Its specific name, pithecoides, derives from the Greek word pithekos, meaning "monkey" or "ape", and the Greek suffix -oides, meaning "like" or "form", and reflects Standing's impression that the animal resembled monkeys in form.[5][10][11] It was a small to medium-sized lemur,[12] weighing approximately 10 kg (22 lb) and having an intermembral index (ratio of limb proportions) of 99.[1] Its skull was similar to that of M. globiceps, but had a broader snout and was more robust, particularly in its sagittal and nuchal crests (ridges on the skull for muscle attachments) and massive zygomatic arches (cheekbones).[1][2] Its skull length averaged 98 mm (3.9 in),[1] ranging from 94.0 to 103.1 mm (3.70 to 4.06 in).[7] It was predominantly folivorous (leaf-eating), but also consumed some fruit and (rarely) seeds.[13][14] It was moderately abundant on the high, central plateau of Madagascar.[12][13][15] It shared its range with the larger sloth lemurs, Palaeopropithecus maximus and Archaeoindris fontoynontii.[15] One sample of its subfossil remains has been radiocarbon dated, yielding a date of 570–679 CE.[1]

- M. globiceps was discovered in 1936 and originally classified in its own genus, Neopropithecus.[2] The name globiceps comes from its prominent forehead[16] and derives from the Latin word globus, meaning "ball", and the New Latin suffix -ceps, meaning "head".[17][18] Like M. pithecoides, it was a small to medium-sized lemur,[12] weighing approximately 11 kg (24 lb) and having an intermembral index of 97.[1] It had the most narrow snout and gracile skeleton of the Mesopropithecus species, similar to but smaller than M. pithecoides, making it more like the living sifakas.[1][2] Its teeth were similar to but larger than those of living sifakas, except for its lower premolars, which were shorter, and the M3 (third upper molar), which was moderately constricted by the cheek and tongue. Its skull length averaged 94 mm (3.7 in),[1] ranging from 93.4 to 94.8 mm (3.68 to 3.73 in).[7] It was a mixed feeder, eating fruit, leaves, and a moderate amount of seeds,[13] having a diet similar to that of the living Indri (Indri indri).[14] Although its forelimbs were more like those of living indriids, its hindlimbs and axial skeleton (skull, spine, and ribs) were more specialized for suspension, as in Palaeopropithecus and Babakotia.[1] It was found in the south and west of Madagascar.[15] Three samples of its subfossil remains have been radiocarbon dated, yielding dates of 354–60 BCE, 58–247 CE, and 245–429 CE.[1]

- M. dolichobrachion was discovered in 1986 and formally described in 1995. It was found in the caves of Ankarana, northern Madagascar, around the same time that the first remains of Babakotia were unearthed.[7] The species name dolichobrachion is Greek, coming from dolicho- ("long") and brachion ("arm"), and means "long-armed".[7][19][20] It was a medium-sized lemur,[12] slightly larger than the other two members of its genus,[7] weighing approximately 14 kg (31 lb).[1] It differed significantly from the other two in its limb proportions and its postcranial morphology.[7][15] Most notably, it was the only species in the genus to have forelimbs that were longer than the hindlimbs, due to a substantially longer and more robust humerus (yielding an intermembral index of 113), as well as more curved phalanges (finger and toe bones).[1][7][21][22] For these reasons, it is thought to have been more sloth-like in its use of suspension.[1][12][21] This was further supported by a study of a single lumbar vertebra. This vertebra was similar to that of Babakotia in having a moderately reduced, dorsally oriented spinous process and a transverse processes (plates of bone that protrude from the vertebrae) that points to the side (laterally). The vertebra was intermediate in length when compared with other sloth lemurs, and its laminae (two plates of bone that connect to the spinous process) were not as broad as seen in Palaeopropithecus.[23] In M. dolichobrachion, skull length averaged 102 mm (4.0 in),[1] ranging from 97.8 to 105.5 mm (3.85 to 4.15 in).[7] The only notable difference from the two other species in its teeth was that the third upper molar had a relatively wider trigon and smaller talon (groups of cusps on the molar teeth).[1] It was a mixed feeder, eating leaves, fruits, and seeds.[13][14] This species was more of a seed predator than the other two species, but was not as specialized as closely related Babakotia radofilai.[14] M. dolichobrachion was rare[12] and shared its range with two other sloth lemurs, Babakotia radofilai and Palaeopropithecus maximus.[3][15] It was the most distinct member of its genus and was geographically restricted to the extreme north of the island.[1]

Anatomy and physiology

| Mesopropithecus placement within the lemur phylogeny[8][24][25] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The genus Mesopropithecus includes some of the smallest of the recently extinct subfossil lemurs, but all species were still noticeably larger than all living (extant) lemurs. They ranged in weight from 10 to 14 kg (22 to 31 lb).[1][2][13] They were also the least specialized of the sloth lemurs, more closely resembling living indriids in both skull and postcranial characteristics.[15] Skull length ranged from 93.4 to 105.5 mm (3.68 to 4.15 in).[7] The dentition and cranial proportions, however, more closely resembled those of the sifakas.[2] The dental formula of Mesopropithecus was the same as in the other sloth lemur and indriids: either 2.1.2.31.1.2.3[2][6] or 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 × 2 = 30.[3] Mesopropithecus had a four-toothed toothcomb, like all indriids and most other sloth lemurs.[1][9] It is unclear whether one of the permanent teeth in the toothcomb is an incisor or canine, resulting in the two conflicting dental formulae.[26] Like other sloth lemurs and indriids, Mesopropithecus had rapid tooth development.[1]

Despite the similarities, there are several features that distinguish Mesopropithecus skulls from those of living indriids. The skull, including the zygomatic arch, is more robustly built. The temporal lines join together anteriorly into a sagittal crest and there is a distinct nuchal ridge that joins the rear of the zygomatic arch. The skull has a more rounded braincase, slightly smaller and more convergent orbits, more pronounced postorbital constriction (narrowing of the skull behind the eye sockets), more robust postorbital bar (bone that encircles the eye socket), a steeper facial angle, more robust and cranially convex zygomatic bone, and a broader, squared snout. The upper incisors and canines are larger.[1][2][3][7] The more robust mandible (lower jaw) and mandibular symphysis (point where the two halves of the lower jaw meet) suggest a more folivorous diet, which requires extra grinding. The orbits are as large (in absolute size) as those in smaller living indriids,[15] which suggests low visual acuity.[27] Mesopropithecus and its closest sloth lemur relative, Babakotia, did share a few ancestral traits with indriids, unlike the largest sloth lemurs, Palaeopropithecus and Archaeoindris. These include the aforementioned four-toothed toothcomb, an inflated auditory bulla (bony structure that encloses part of the middle and inner ear), and an intrabullar ectotympanic ring (bony ring that holds the eardrum).[1]

While the skull of Mesopropithecus most closely resembles that of modern sifakas, the postcranial skeleton is quite different. Rather than having elongated hindlimbs for leaping, Mesopropithecus had elongated forelimbs, suggesting they predominantly used quadrupedal locomotion, slow climbing, with some forelimb and hindlimb suspension.[2][8][9][13] In fact, they were the most quadrupedal of the sloth lemurs,[13][15][21] having an intermembral index between 97 and 113, compared to the lower value for indriids and higher values for the other sloth lemurs.[1][15] (In arboreal primates, an intermembral index of 100 predicts quadrupedalism, higher values predict suspensory behavior, and lower values predict leaping behavior.)[28] Wrist bones found in 1999 further demonstrate that Mesopropithecus was a vertical climber[29] and the most loris-like of the sloth lemurs.[9] Analysis of a lumbar vertebra of M. dolichobrachion further supported this conclusion.[23]

Our understanding of the morphology of Mesopropithecus has not always been so complete. Until recently, important pieces of the skeleton had not been discovered, including the radius, ulna, vertebrae, hand and foot bones, and the pelvis. In 1936, Alice Carleton mistakenly associated postcranial remains of the Diademed Sifaka (Propithecus diadema) from Ampasambazimba with Mesopropithecus pithecoides and came to the false conclusion that its morphology was like that of a monkey. This mistaken attribution was corrected in 1948 by Charles Lamberton.[9]

Distribution and ecology

Mesopropithecus species appear to have been generally rare within their wide range. Collectively, the three species have been found in the north, south, west, and center of Madagascar,[15] although they appear to have been geographically separated (allopatric) from each other.[3] Subfossil discoveries indicate that they lived in the same region (sympatric) with other sloth lemurs in the north and center of Madagascar.[15] The subfossil remains of M. globiceps have been found at seven subfossil sites on Madagascar: Anavoha, Ankazoabo-Grotte, Belo sur Mer, Manombo-Toliara, Taolambiby, Tsiandroina, Tsirave.[1] The subfossil remains of both M. pithecoides and M. dolichobrachion have only been found at one site each, Ampasambazimba and Ankarana respectively.[1]

M. pithecoides from the central plateau was a specialized leaf-eater (folivore), but the other two species had a more mixed diet, eating fruits and seeds in addition to leaves.[13][14][15] The level of seed predation varies between the three species, with tooth wear indicating that M. dolichobrachion exhibited the greatest level of seed predation within the genus.[14]

Extinction

Because Mesopropithecus died out relatively recently and is only known from subfossil remains, it is considered to be a modern form of Malagasy lemur.[12] It may have been among the last subfossil lemurs to go extinct, possibly surviving until 500 years ago,[2][30] although radiocarbon dating places the most recent remains at 570–679 CE for a M. pithecoides from Ampasambazimba.[1][30] The arrival of humans roughly 2,000 years ago is thought to have sparked the decline of Mesopropithecus through hunting, habitat destruction, or both.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 Godfrey, Jungers & Burney 2010, Chapter 21

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Nowak 1999, pp. 89–91

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Godfrey & Jungers 2002, pp. 108–110

- ↑ McKenna & Bell 1997, p. 336

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Standing, H.F. (1905). "Rapport sur des ossements sub-fossiles provenant d'Ampasambazimba" [Report on subfossil bones from Ampasambazimba]. Bulletin de l'Académie malgache (in French) 4: 95–100.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mittermeier et al. 1994, pp. 33–48

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 Simons, E.L.; Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Chatrath, P.S.; Ravaoarisoa, J. (1995). "A new species of Mesopropithecus (Primates, Palaeopropithecidae) from Northern Madagascar". International Journal of Primatology 15 (5): 653–682. doi:10.1007/BF02735287.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Godfrey & Jungers 2003, pp. 1247–1252

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2003). "The extinct sloth lemurs of Madagascar" (PDF). Evolutionary Anthropology 12 (6): 252–263. doi:10.1002/evan.10123.

- ↑ Borror 1988, p. 76

- ↑ Borror 1988, p. 66

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Sussman 2003, pp. 107–148

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 37–51

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Godfrey, L.R.; Semprebon, G.M.; Jungers, W.L.; Sutherland, M.R.; Simons, E.L.; Solounias, N. (2004). "Dental use wear in extinct lemurs: evidence of diet and niche differentiation" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution 47 (3): 145–169. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.06.003. PMID 15337413.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 15.9 15.10 15.11 Godfrey et al. 1997, pp. 218–256

- ↑ Lamberton, C. (1936). "Nouveaux lémuriens fossiles du groupe des Propithèques et l'intérêt de leur découverte" [New fossil lemurs of the group Propithecus and the significance of their discovery]. Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. 2 (in French) 8: 370–373.

- ↑ Borror 1988, p. 43

- ↑ Borror 1988, p. 23

- ↑ Borror 1988, p. 33

- ↑ Borror 1988, p. 58

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Simons 1997, pp. 142–166

- ↑ Jungers, W.L.; Godfrey, L.R.; Simons, E.L.; Chatrath, P.S.; Williamson, J.R. (1997). "Phalangeal curvature and positional behavior in extinct sloth lemurs (Primates, Palaeopropithecidae)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 94 (1): 11998–12001. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9411998J. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.22.11998. PMC 23681. PMID 11038588.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Shapiro, L.J.; Seiffert, C.V.M.; Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Simons, E.L.; Randria, G.F.N. (2005). "Morphometric analysis of lumbar vertebrae in extinct Malagasy strepsirrhines" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology 128 (4): 823–839. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20122. PMID 16110476.

- ↑ Horvath, J.; Weisrock, D.W.; Embry, S.L.; Fiorentino, I.; Balhoff, J.P.; Kappeler, P.; Wray, G.A.; Willard, H.F.; Yoder, A.D. (2008). "Development and application of a phylogenomic toolkit: Resolving the evolutionary history of Madagascar's lemurs" (PDF). Genome Research 18 (3): 489–499. doi:10.1101/gr.7265208. PMC 2259113. PMID 18245770.

- ↑ Orlando, L.; Calvignac, S.; Schnebelen, C.; Douady, C.J.; Godfrey, L.R.; Hänni, C. (2008). "DNA from extinct giant lemurs links archaeolemurids to extant indriids". BMC Evolutionary Biology 8: 121. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-121. PMC 2386821. PMID 18442367.

- ↑ Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 253–257

- ↑ Godfrey, Jungers & Schwartz 2006, pp. 41–64

- ↑ Ankel-Simons 2007, pp. 49–53

- ↑ Hamrick, M.W.; Simons, E.L.; Jungers, W.L. (2000). "New wrist bones of the Malagasy giant subfossil lemurs". Journal of Human Evolution 38 (5): 635–650. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0372. PMID 10799257.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Burney, D.A.; Burney, L.P.; Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Goodman, S.M.; Wright, H.T.; Jull, A.J.T. (2004). "A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution 47 (1–2): 25–63. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. PMID 15288523.

- Books cited

- Ankel-Simons, F. (2007). Primate Anatomy (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-372576-3.

- Borror, D.J. (1988). Dictionary of Word Roots and Combining Forms. Mayfield Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87484-053-7. (Note: this book was first published 1960)

- Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P., eds. (2003). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30306-3.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2003). "Subfossil Lemurs". pp. 1247–1252. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2003). "Subfossil Lemurs". pp. 1247–1252. Missing or empty

- Goodman, S.M.; Patterson, B.D., eds. (1997). Natural Change and Human Impact in Madagascar. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-682-9.

- Simons, E.L. (1997). "Chapter 6: Lemurs: Old and New". pp. 142–166. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Reed, K.E.; Simons, E.L.; Chatrath, P.S. (1997). "Chapter 8: Subfossil Lemurs". pp. 218–256. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Simons, E.L. (1997). "Chapter 6: Lemurs: Old and New". pp. 142–166. Missing or empty

- Gould, L.; Sauther, M.L., eds. (2006). Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-34585-7.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Schwartz, G.T. (2006). "Chapter 3: Ecology and Extinction of Madagascar's Subfossil Lemurs". pp. 41–64. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Schwartz, G.T. (2006). "Chapter 3: Ecology and Extinction of Madagascar's Subfossil Lemurs". pp. 41–64. Missing or empty

- Hartwig, W.C., ed. (2002). The Primate Fossil Record. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66315-6.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2002). "Chapter 7: Quaternary fossil lemurs". pp. 108–110. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L. (2002). "Chapter 7: Quaternary fossil lemurs". pp. 108–110. Missing or empty

- McKenna, M.C.; Bell, S.K. (1997). Classification of Mammals: Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-231-11013-6.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Konstant, W.R.; Hawkins, F.; Louis, E.E. et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (2nd ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 1-881173-88-7. OCLC 883321520.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Tattersall, I.; Konstant, W.R.; Meyers, D.M.; Mast, R.B. (1994). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (1st ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 1-881173-08-9. OCLC 32480729.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- Sussman, R.W. (2003). Primate Ecology and Social Structure. Pearson Custom Publishing. ISBN 978-0-536-74363-3.

- Werdelin, L.; Sanders, W.J., eds. (2010). Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25721-4.

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Burney, D.A. (2010). "Chapter 21: Subfossil Lemurs of Madagascar". Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Godfrey, L.R.; Jungers, W.L.; Burney, D.A. (2010). "Chapter 21: Subfossil Lemurs of Madagascar". Missing or empty