Merkle–Hellman knapsack cryptosystem

The Merkle–Hellman knapsack cryptosystem was one of the earliest public key cryptosystems invented by Ralph Merkle and Martin Hellman in 1978.[1] The ideas behind it are simpler than those involving RSA, and it has been broken.[2]

Description

Merkle-Hellman is an asymmetric-key cryptosystem, meaning that two keys are required for communication: a public key and a private key. Furthermore, unlike RSA, it is one-way: the public key is used only for encryption, and the private key is used only for decryption. Thus it is unusable for authentication by cryptographic signing.

The Merkle-Hellman system is based on the subset sum problem (a special case of the knapsack problem). The problem is as follows: given a set of numbers A and a number b, find a subset of A which sums to b. In general, this problem is known to be NP-complete. However, if the set of numbers (called the knapsack) is superincreasing, meaning that each element of the set is greater than the sum of all the numbers before it, the problem is "easy" and solvable in polynomial time with a simple greedy algorithm.

Key generation

In Merkle-Hellman, the keys are two knapsacks. The public key is a 'hard' knapsack A, and the private key is an 'easy', or superincreasing, knapsack B, combined with two additional numbers, a multiplier and a modulus. The multiplier and modulus can be used to convert the superincreasing knapsack into the hard knapsack. These same numbers are used to transform the sum of the subset of the hard knapsack into the sum of the subset of the easy knapsack, which is a problem that is solvable in polynomial time.

Encryption

To encrypt a message, a subset of the hard knapsack A is chosen by comparing it with a set of bits (the plaintext) equal in length to the key. Each term in the public key that corresponds to a 1 in the plaintext is an element of the subset A_m, while terms that corresponding to 0 in the plaintext are ignored when constructing A_m - they are not elements of the key. The elements of this subset are added together and the resulting sum is the ciphertext.

Decryption

Decryption is possible because the multiplier and modulus used to transform the easy knapsack into the public key can also be used to transform the number representing the ciphertext into the sum of the corresponding elements of the superincreasing knapsack. Then, using a simple greedy algorithm, the easy knapsack can be solved using O(n) arithmetic operations, which decrypts the message.

Mathematical method

Key generation

To encrypt n-bit messages, choose a superincreasing sequence

- w = (w1, w2, ..., wn)

of n nonzero natural numbers. Pick a random integer q, such that

-

,

,

and a random integer, r, such that gcd(r,q) = 1 (i.e. r and q are coprime).

q is chosen this way to ensure the uniqueness of the ciphertext. If it is any smaller, more than one plaintext may encrypt to the same ciphertext. Since q is larger than the sum of every subset of w, no sums are congruent mod q and therefore none of the private key's sums will be equal. r must be coprime to q or else it will not have an inverse mod q. The existence of the inverse of r is necessary so that decryption is possible.

Now calculate the sequence

- β = (β1, β2, ..., βn)

where

- βi = rwi mod q.

The public key is β, while the private key is (w, q, r).

Encryption

To encrypt an n-bit message

- α = (α1, α2, ..., αn),

where  is the i-th bit of the message and

is the i-th bit of the message and  {0, 1}, calculate

{0, 1}, calculate

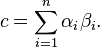

The cryptogram then is c.

Decryption

In order to decrypt a ciphertext c a receiver has to find the message bits αi such that they satisfy

This would be a hard problem if the βi were random values because the receiver would have to solve an instance of the subset sum problem, which is known to be NP-hard. However, the values βi were chosen such that decryption is easy if the private key (w, q, r) is known.

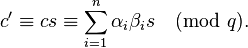

The key to decryption is to find an integer s that is the modular inverse of r modulo q. That means s satisfies the equation s r mod q = 1 or equivalently there exist an integer k such that sr = kq + 1. Since r was chosen such that gcd(r,q)=1 it is possible to find s and k by using the Extended Euclidean algorithm. Next the receiver of the ciphertext c computes

Hence

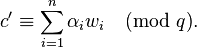

Because of rs mod q = 1 and βi = rwi mod q follows

Hence

The sum of all values wi is smaller than q and hence  is also in the interval [0,q-1].

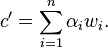

Thus the receiver has to solve the subset sum problem

is also in the interval [0,q-1].

Thus the receiver has to solve the subset sum problem

This problem is easy because w is a superincreasing sequence. Take the largest element in w, say wk. If wk > c' , then αk = 0, if wk≤c' , then αk = 1. Then, subtract wk×αk from c' , and repeat these steps until you have figured out α.

Example

First, a superincreasing sequence w is created

w = {2, 7, 11, 21, 42, 89, 180, 354}

This is the basis for a private key. From this, calculate the sum.

Then, choose a number q that is greater than the sum.

q = 881Also, choose a number r that is in the range  and is coprime to q.

and is coprime to q.

r = 588The private key consists of q, w and r.

To calculate a public key, generate the sequence β by multiplying each element in w by r mod q

β = {295, 592, 301, 14, 28, 353, 120, 236}

because

(2 * 588) mod 881 = 295 (7 * 588) mod 881 = 592 (11 * 588) mod 881 = 301 (21 * 588) mod 881 = 14 (42 * 588) mod 881 = 28 (89 * 588) mod 881 = 353 (180 * 588) mod 881 = 120 (354 * 588) mod 881 = 236

The sequence β makes up the public key.

Say Alice wishes to encrypt "a". First, she must translate "a" to binary (in this case, using ASCII or UTF-8)

01100001

She multiplies each respective bit by the corresponding number in β

a = 01100001

0 * 295

+ 1 * 592

+ 1 * 301

+ 0 * 14

+ 0 * 28

+ 0 * 353

+ 0 * 120

+ 1 * 236

= 1129She sends this to the recipient.

To decrypt, Bob multiplies 1129 by r −1 mod  (See Modular inverse)

(See Modular inverse)

1129 * 442 mod 881 = 372Now Bob decomposes 372 by selecting the largest element in w which is less than or equal to 372. Then selecting the next largest element less than or equal to the difference, until the difference is  :

:

372 - 354 = 1818 - 11 = 77 - 7 = 0

The elements we selected from our private key correspond to the 1 bits in the message

01100001When translated back from binary, this "a" is the final decrypted message.

References

- ↑ Merkle, Ralph; Hellman, Martin (1978). "Hiding information and signatures in trapdoor knapsacks". Information Theory, IEEE Transactions on 24 (5): 525–530. doi:10.1109/TIT.1978.1055927.

- ↑ Shamir, Adi (1984). "A polynomial-time algorithm for breaking the basic Merkle - Hellman cryptosystem". Information Theory, IEEE Transactions on 30 (5): 699–704. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1982.5.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||