Membrane gas separation

Gas mixtures can be effectively separated by synthetic membranes made from polymers such as polyamide or cellulose acetate, or from ceramic materials.[1]

Makeup

Synthetic membranes are made from a variety of polymers including polyethylene, polyamides, polyimides, cellulose acetate, polysulphone and polydimethylsiloxan.[2]

Membrane types

There are two types of membrane separator, each working through a different mechanism.

Non-porous

Also known as dense-film membranes. Above the glass transition temperature amorphous segments of polymer exhibit liquid-like properties and allow gases to pass through by a solution diffusion mechanism. Temperature has a very significant effect which gives transport rates according to the Arrhenius equation.[2]

Non-porous membranes are highly selective but must be very thin to achieve reasonable capacities per unit area. This limits their mechanical strength.[2]

Small molecules of penetrants move among polymer chains according to the formation of local gaps by thermal motion of polymer segments. The free volume of the polymer, its distribution and local changes in distribution are of the utmost importance. The diffusivity of a penetrant depends mainly on its molecular size.

Porous

Porous membranes typically contain larger voids than non-porous membranes which have interconnected pores significantly larger than the molecular diameters of gases passing through them. Transfer through the pores depends on structure and size distribution. Selectivity is determined primarily by the relative molecular sizes of the gases being separated, giving poorer selectivity. Unlike non-porous membranes, porous membranes exhibit no molecular interaction between the membrane polymer and the diffusing species.[2]

Porous membranes can be made much thicker than non-porous membranes and retain high capacities with good mechanical strength so despite their reduced selectivity they are commonly used for bulk separation.[2]

The pore diameter must be smaller than the mean free path of gas molecules. Under normal conditions (100 kPa, 300 K), this is about 50 nm. In this case, the gas flux through the pore is proportional to the molecule's velocity, i.e., inversely proportional to the square root of the molecule's mass. This is known as Knudsen diffusion. Gas flux through a porous membrane is much higher than through a nonporous one by 3 to 5 orders of magnitude. The separation efficiency is moderate; hydrogen diffuses 4 times faster than oxygen. Porous polymeric or ceramic membranes for ultrafiltration serve the purpose. Note that when the pores are larger than the limit then viscous flow occurs, and hence there is no separation.

Other Membrane Technologies

In special cases other materials can be utilized; for example, palladium membranes permit transport solely of hydrogen.[3] In addition to palladium membranes (which are typically palladium silver alloys to stop embrittlement of the alloy at lower temperature) there is also a significant research effort looking into finding non-precious metal alternatives. Although slow kinetics of exchange on the surface of the membrane and tendency for the membranes to crack or disintegrate after a number of duty cycles or during cooling are problems yet to be fully solved.[4]

Construction

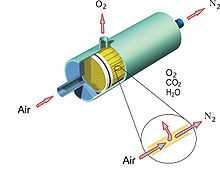

Membranes are typically contained in one of three modules:[2]

- Hollow fibre bundles in a metal module

- Spiral wound bundles in a metal module

- plate and frame module constructed like a plate and frame heat exchanger

Uses

Membranes are employed in:[1]

- Recovery of hydrogen from product streams of ammonia plants

- Recovery of hydrogen in oil refinery processes

- Separation of methane from the other components of biogas

- Enrichment of air by oxygen for medical or metallurgical purposes

- Enrichment of ullage by nitrogen in Inerting systems designed to prevent fuel tank explosions

- Removal of water vapor from natural gas and other gasesFurther information: Membrane driers

- Removal of volatile organic liquids (VOL) from air of exhaust streams

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kerry, Frank (2007). Industrial Gas Handbook: Gas Separation and Purification. CRC Press. pp. 275–280. ISBN 9780849390050.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Isalski, W. H. (1989). Separation of Gases. Monograph on Cryogenics 5. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 228–233.

- ↑ Yun, S.; Ted Oyama, S. (2011). "Correlations in palladium membranes for hydrogen separation: A review". Journal of Membrane Science 375: 28. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2011.03.057.

- ↑ Dolan, Michael D.; Kochanek, Mark A.; Munnings, Christopher N.; McLennan, Keith G.; Viano, David M. (February 2015). "Hydride phase equilibria in V–Ti–Ni alloy membranes". Journal of Alloys and Compounds 622: 276–281. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.10.081.

- Vieth, W.R. (1991). Diffusion in and through Polymers. Munich: Hanser Verlag. ISBN 9783446155749.

See also

| ||||||||||||||