Meisenheim

| Meisenheim | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| ||

Meisenheim | ||

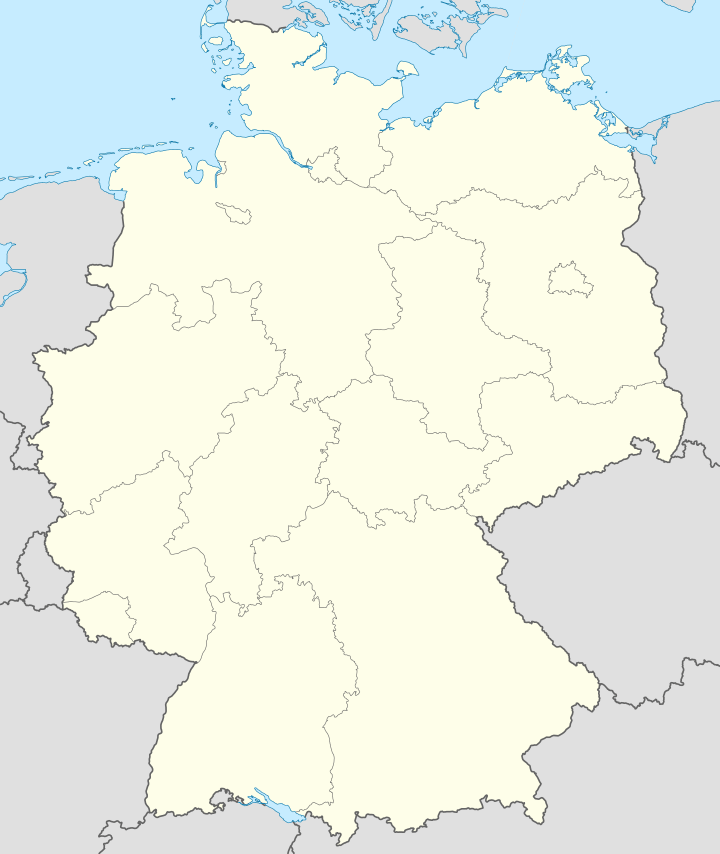

Location of Meisenheim within Bad Kreuznach district  | ||

| Coordinates: 49°43′N 07°40′E / 49.717°N 7.667°ECoordinates: 49°43′N 07°40′E / 49.717°N 7.667°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| District | Bad Kreuznach | |

| Municipal assoc. | Meisenheim | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Werner Keym | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 10.34 km2 (3.99 sq mi) | |

| Population (2012-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 2,833 | |

| • Density | 270/km2 (710/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 55590 | |

| Dialling codes | 06753 | |

| Vehicle registration | KH | |

| Website | www.meisenheim.de | |

Meisenheim is a town in the Bad Kreuznach district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the like-named Verbandsgemeinde, and is also its seat. Meisenheim is a state-recognized recreational resort (Erholungsort) and it is set out as a middle centre in state planning.

Geography

Location

Meisenheim lies in the valley of the River Glan at the northern edge of the North Palatine Uplands. The municipal area measures 1 324 ha.[2]

Neighbouring municipalities

Clockwise from the north, Meisenheim’s neighbours are Raumbach, Rehborn, Callbach, Reiffelbach, Odenbach, Breitenheim and Desloch, all of which likewise lie within the Bad Kreuznach district, except for Odenbach, which lies in the neighbouring Kusel district.

Constituent communities

Also belonging to Meisenheim are the outlying homesteads of Hof Wieseck, Keddarterhof and Röther Hof.[3]

History

Meisenheim is believed to have arisen in the 7th century AD, and its name is often derived from the town’s hypothetical founder “Meiso” (thus making the meaning “Meiso’s Home”). In 1154, Meisenheim had its first documentary mention. Sometimes cited as such, however, is a document dated 14 June 891 from the West Frankish king Odo (for example by K. Heintz in Die Schlosskirche zu Meisenheim a. Gl. u. ihre Denkmäler in Mitteilungen d. Histor. Vereins d. Pfalz 24 (1900) pp. 164–279, within which p. 164, and by W. Dotzauer in Geschichte des Nahe-Hunsrück-Raumes (2001), pp. 69 & 72), but this document is falsified (cf. H. Wibel: Die Urkundenfälschungen Georg Friedrich Schotts, in Neues Archiv d. Ges. f. Ältere Dt. Gesch.kunde Bd. 29 (1904), pp. 653–765, within which p. 688 & pp. 753– 757[4]). In the 12th century, Meisenheim was raised to the main seat of the Counts of Veldenz and in 1315 it was granted town rights by King Ludwig IV. On what is now known as Schlossplatz (“Palace Square”), the Counts of Veldenz built a castle, bearing witness to which today are only two buildings that were later built, the “Schloss Magdalenenbau” (nowadays called the Herzog-Wolfgang-Haus or “Duke Wolfgang House”) and above all the Schlosskirche (“Palace Church”), building work on which began in 1479. Both buildings were built only after the Counts of Veldenz had died out in 1444 and the county had been inherited by the Dukes of Palatinate-Zweibrücken. This noble house, too, at first kept their seat at Meisenheim, but soon moved it to Zweibrücken. From 1538 to 1571, Duke Wolfgang of Zweibrücken maintained in Meisenheim a mint, with one interruption, although this was then moved to Bergzabern. The Doppeltaler (double Thaler), Taler (Thaler) and Halbtaler (half Thaler) coins minted in the time when the mint was in Meisenheim remain among the highest-quality mintings from Palatinate-Zweibrücken. In 1799, Duke of Zweibrücken Maximilian IV inherited besides the land that he already held the long united lands of the Electorate of Bavaria and Electoral Palatinate. While these three countries were now de jure in personal union, this did not shift the power structures on the ground at all, for Palatinate-Zweibrücken had already been occupied by French Revolutionary troops. Because of the terms of the Congress of Vienna (1815), the part of Palatinate-Zweibrücken lying north of the Glan, and thus Meisenheim too, were assigned not to the Kingdom of Bavaria but rather to the Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg. From 1816 onwards, Meisenheim was the administrative seat of the Oberamt of Meisenheim and an Oberschultheißerei. In 1866, the Grand Duchy of Hesse inherited the whole territory, but after losing a war later that same year, the grand duchy had to cede Hesse-Homburg to the Kingdom of Prussia. The town of Meisenheim itself was not wholly reunited until after the Second World War when state of Rhineland-Palatinate was founded. Until then, the lands just across the Glan had been Bavarian (either as foreign territory or as another province within Imperial, Weimar or Nazi Germany) since the Congress of Vienna.

Jewish history

Meisenheim had a Jewish community possibly even as far back as the Middle Ages, after it was granted town rights in 1315. The first documentary mention of a Jew, however, did not come until 1551 when a “Jud Moses” cropped up in the record. He was selling a house on Schweinsgasse (a lane that still exists now). In 1569, the Jews were turned out of the town. After the Thirty Years' War, two Jewish families were allowed to live in the town. In 1740, the number of Jewish families was still supposed to be kept down to four, but this rule was often not upheld. The reasons given for these restrictions were mainly economic.

…Fourteenthly, no more than four Jewish families should live and be tolerated in the local town; this rose under High Prince Gustav’s state government to 7 such, …which has not only caused the local grocers through the constant hawking and the butchers through shechita great harm and loss of sustinence, but also has already put many citizens and peasants to ruination, and furthermore still means that the little protection money that Your High-Princely Serene Highness draws from these people by far does not offset this harm, whereby Your High-Princely Serene Highness harms his truest subjects. If a few provisions have been indulged-in as a result of the hawking and shechita, bizarrely the butchers’ guild article, then these Jews, as a dogged and naughty people, are not troubled by them, but rather begin their abuses anew after some time has gone by; we therefore ask, most humbly, that Your High-Princely Serene Highness most kindly deign to reduce the Jews here, to the citizenry’s greatest consolation, back to 4, by strengthening the provisions for the forbidden hawking and the butchers’ guild article for excessive shechita.

Following the 1740 decree, the Jews moved to nearby villages, still keeping themselves near the “market”, which to them was a matter of survival, and which was of course also necessary for economic growth. The “grocers” and above all the butchers could thus not be wholly free of their competition, especially as the government knew enough to prize good taxpayers. This shift also applied across borders, and thus not only to the villages belonging to the canton of Meisenheim, but also to the bordering Palatine villages such as Odenbach. A thorougher analysis of this shift of town and country Jews appears in W. Kemp’s review, and this work also contains a taxation roll of Jews in the canton of Meisenheim, showing the tax burdens borne by Jews living in the outlying villages of Medard, Breitenheim, Schweinschied, Löllbach, Merxheim, Bärweiler, Meddersheim, Staudernheim and Hundsbach. The modern Jewish community arose in the 18th century, According to a report from 1860, the oldest readable gravestone then at the Meisenheim graveyard bore the date 1725. Thus presumably Jews were then still allowed to live in the town. In the time of the French Revolution, there were fewer Jewish families, among whom was a butcher who was allowed to ply his trade in town. About 1800, it is clear that several families fled to the town to escape Johannes Bückler’s (Schinderhannes’s) crimewave. In the earlier half of the 19th century, the number of Jewish inhabitants grew sharply, mostly because of the arrival of newcomers from Jewish villages in the Hunsrück area. The number of Jewish inhabitants developed as follows: in 1808, there were 161; in 1860, 260; in 1864, 198 (12% of the population); in 1871, 160 (8.73% of 1,832 inhabitants); in 1885, 120 (7.05% of 1701); in 1895, 87 (5.01% of 1738); in 1902, 89 (5.01% of 1,777). Also belonging to the Breitenheim Jewish community were the Jews living in Breitenheim. In 1924 they numbered two. In the way of institutions, there were a synagogue (see Former synagogue below), a Jewish primary and religious school (present no later than 1826, and as of 1842 housed in the building at Wagnerstraße 13), a mikveh and a graveyard (see Jewish graveyard below). To provide for the community’s religious needs, a primary and religious schoolteacher, alongside the rabbi, was hired, who also busied himself as the hazzan and the shochet (preserved is a whole series of job advertisements for such a position in Meisenheim from such publications as the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums). For a time, the hazzan’s position was separate from the schoolteacher’s. In the 19th century, a man named Benjamin Unrich worked as primary schoolteacher from 1837 to 1887 – 50 years. In 1830, he taught 32 children, in 1845, 46 and in 1882, 21. At either Unrich’s retirement or his death in 1890, the Jewish primary school was closed, and thereafter Jewish schoolchildren attended the Evangelical school, while receiving religious instruction at the Jewish religious school. 1875 to 1909, the community’s hazzan and religion teacher was Heyman de Beer. The last religion teacher, from 1924 to 1928, was Julius Voos (b. 1904 in Kamen, Westphalia, d. 1944 at Auschwitz). In 1924, he taught 15 children, but by 1928, this had shrunk to 7. After he left, the few school-age Jewish children left were taught by the schoolteacher from Sobernheim (Julius Voos earned his doctorate in Bonn in 1933, and between 1936 and 1943 he was a rabbi in in Guben, Lusatia, then in Münster, whence he was deported to Auschwitz in 1943). Meisenheim was in the 19th century the seat of a rabbinate, with the rabbi bearing the title Landesrabbiner of the Oberamt of Meisenheim in Hesse-Homburg times and Kreisrabbiner (“District Rabbi”) in Prussian times. Serving as rabbi were the following:

| Tenure | Name | Birth | Death | Education | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ????–1835 | Isaac Hirsch Unrich | ? | ? | ? | Presumably Meisenheim’s first rabbi |

| 1835–1845 | – | – | – | – | Post vacant for lack of funds |

| 1845–1861 | Baruch Hirsch Flehinger | 1809 in Flehingen | 1890 | after 1825 Mannheim Yeshiva, 1830–1833 University of Heidelberg | 1845–1861 State Rabbi in Meisenheim, thereafter in Merchingen; also responsible from 1870 for Tauberbischofsheim rabbinical region |

| 1861–1869 | Lasar Latzar | 1822 in Galicia | 1869 in Meisenheim | ? | ~1856 regional rabbi in Kikinda, Vojvodina; lost job in 1860 to Magyarization of school and worship |

| 1870–1879 | Dr. Israel Mayer (Meyer) | 1845 in Müllheim, Baden | 1898 in Zweibrücken | 1865–1871 Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau | Quit after 1873 cut in rabbinical salary subsidy; office transferred in 1877 to hazzan; went to new rabbinical post in Zweibrücken in 1879 |

| 1879–1882 | Dr. Salomon (Seligmann) Fried | 1847 in Ó-Gyalla, Hungary | 1906 in Ulm | 1871–1879 University and Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau | 1870 District Rabbi in Meisenheim, Rabbi in Bernburg (1883), Ratibor (1884) and Ulm (1888 until his death) |

| 1882–1883 | Dr. Moritz Janowitz | 1850 in Eisenstadt, Hungary | 1919 in Berlin | 1871–1878 University and Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau | Rabbi in Písek, Bohemia (1876), Meisenheim (1882), thereafter in Dirschau, West Prussia, rabbi and head of Ahawas Thora synagogue association’s religion school in Berlin (~1896) |

One member of Meisenheim’s Jewish community fell in the First World War, Leo Sender (b. 12 July 1893 in Hennweiler, d. 20 October 1914). Also lost in the Great War was Alfred Moritz (b. 16 May 1890 in Meisenheim, d. 20 June 1916), but he had moved to Kirn by 1914. About 1924, when there were still 55 members of the Jewish community (3% of roughly 1,800 to 1,900 inhabitants), the community’s leaders were Moritz Rosenberg, Simon Schlachter, Albert Kaufmann and Hermann Levy. The representatives were Louis Strauß, Levi Bloch, Albert Cahn and Siegmund Cahn. Employed as schoolteacher was Julius Voos. He taught at the community’s religion school and taught Jewish religion at the public schools. In 1932, the community’s leaders were Moritz Rosenberg (first), Simon Schlachter (second) and Felix Kaufmann (third). The community had since found itself without a schoolteacher. Instruction was then being given the Jewish schoolchildren by Felix Moses from Sobernheim. Worthy of mention among the then still active Jewish clubs is the Jewish Women’s Club, which concerned itself with supporting the poor. In 1932 its chairwoman was Mrs. Schlachter. In 1933, the year when Adolf Hitler and the Nazis seized power, there were still 38 Jews living in 13 families in Meisenheim. Thereafter, though, some of the Jews moved away or even emigrated in the face of the progressive stripping of their rights and repression, all brought about by the Nazis. Already by that year, intimidating measures were being undertaken: Shochet’s knives were being seized by Brownshirt and Stahlhelm thugs. Several well known Jewish businessmen (grain wholesaler Hugo Weil, wine dealer Julius Levy, other livestock and grain wholesalers) were taken into so-called “protective custody”. Jewish businesses were “Aryanized”, the last ones in June 1938. On Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938), the synagogue sustained substantial damage, and worse, the Jewish men who were still in town were arrested. With the deportation of the last Jews living in Meisenheim to the South of France in October 1940, the Meisenheim Jewish community’s history came to an end. According to the Gedenkbuch – Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933-1945 (“Memorial Book – Victims of the Persecution of the Jews under National Socialist Tyranny”) and Yad Vashem, as compared against other data, critically examined and completed by Wolfgang Kemp, of all Jews who either were born in Meisenheim or lived there for a long time, 44 died in the time of the Third Reich (birthdates in brackets):

- Ferdinand Altschüler (1865)

- Thekla Bär née Fränkel (1862)

- Hedwig de Beer (1887)

- Klara de Beer (1889)

- Cäcilia (Zili) de Beer (1891)

- Sigmund Cahn (1874)

- Ida Cahn née Kaufmann, Sigmund’s wife (1885)

- Adolf David (1879)

- Julius David (1883)

- Leo Fränkel (1867)

- Julius Fränkel (1873)

- Karl Josef Fränkel (1902)

- Pauline Goldmann, née Fränkel (1864)

- Frieda Hamburger, née Schlachter (1885)

- Willy Hamburger, Sohn von Frieda (1911)

- Albert Löb (1870)

- Flora Löb née de Beer (1895)

- Julius Maas (1876)

- Martha Mayer née Fränkel (1866)

- Georg Meyer (1894)

- Selma Meyer, née Schlachter, Georg’s wife, Simon’s and Elise’s daughter (1894)

- Johanna Nathan née Strauss (1873)

- Moritz Rosenberg (1866)

- Auguste Rosenberg née Stern, Moritz’s wife (1863)

- Elsa (Else) Rosenberg, Moritz’s and Auguste’s daughter (1894)

- Flora Sandel née de Beer (1884)

- Justine Scheuer née Fränkel (1861)

- Simon Schlachter (1858)

- Schlachter, Elisabeth Elise, née Sonnheim, Simon’s wife (1867)

- Adele Silberberg née David (1871)

- Simon Schlachter (1877)

- Isidor (Juda, Justin) Stern (1893)

- Walter Stern (1899)

- Ida Strauss née Strauss (1862)

- Isaac Julius Strauss (1866)

- Isaac (called 'Louis/Ludwig') Strauss (1887)

- Laura Strauss née Michel, Louis’s wife (1883)

- Lilli Strauss, Louis’s and Laura’s daughter (1924)

- Rudolf Strauss, Louis’s and Laura’s son (1928)

- Isidor Weil, Jakob’s brother (1875)

- Friederike 'Rika' Weil née Stein, Jakob’s widow (1875)

- Dr. Otto Weil, Jakob’s and his first wife Therese née Schwartz’s son (1894)

- Hedwig Weil née Mayer, wife of Hugo Emanuel, Jakob’s and his second wife Friederike née Stein’s son (1911)

- Alfred Abraham Weil, Hedwig’s and Hugo’s son (1936)

After 1945, the only Jews who came back to Meisenheim were one married couple, Otto David and his wife. Listed in the table that follows are the fates of some of Meisenheim’s Jewish families:

| | | | |

| 1. | Family Ludwig Bloch | | |

| 2. | Family Sigmund Cahn | | |

| 3. | Family Albert Cahn | | |

| 4. | Family Adolph David | | |

| 5. | Family Albert Kaufmann | | |

| 6. | Family Felix Kaufmann | | |

| 7. | Family Hermann Levy | | after living through Kristallnacht in Meisenheim |

| 8. | Albert Loeb | | |

| 9. | Family Julius Loeb | | |

| 10. | Family Moritz Rosenberg | another daughter emigrated | |

| 11. | Family Simon Schlachter | | |

| 12. | Family Isaak Strauß | | |

| 13. | Friederike Unrich | | |

| 14. | Family Jakob Weil | Jakob’s widow Friederike (“Rika”) was murdered at Sobibór; Hugo’s wife Hedwig and their son Alfred Abraham were murdered at Auschwitz; Edith’s parents Isidor and Sophie were murdered at Sobibór | Jakob died in 1937 after a fall down some stairs; son Hugo survived Auschwitz, fleeing a death march; Dr. jur. Otto Weil’s wife Edith “Settchen” née Meier survived Bergen-Belsen with both her sons Edwin and Ralf |

In comparison with the list of victims, it comes to light that idyllic and introspective Meisenheim was gladly sought out by expectant mothers as a place to give birth. Those born in Meisenheim markedly outnumbered those who had moved there. Three persons, who indeed were also born in Meisenheim but whose lives did not centre around it, lived in Mannheim at a seniors’ home and thus were seized in the Saar/Pfalz/Baden-Aktion undertaken by the two Gauleiter Bürckel and Wagner and thereby sent to Gurs. They were Ferdinand Altschüler (76) and the sisters Ida and Johanna Strauss (79 and 68). Now standing in memory of many of those Jews who died or were driven out in the Shoa are so-called Stolpersteine, which were only laid in the town on 23 November 2007 after town council’s unanimous vote in response to the Meisenheim Synagogue Sponsorship and Promotional Association chairman Günter Lenhoff’s proposal.[5]

Criminal history

Like many places in the region, Meisenheim can claim to have had its dealings with the notorious outlaw Schinderhannes (or Johannes Bückler, to use his true name). In early 1797, the already well known robber committed one of his earliest burglaries in Meisenheim. One night, he climbed into a master tanner’s house and stole part of his leather stock, which he then apparently tried to sell back to the tanner the next day.[6] In the spring of 1798, Schinderhannes went dancing several times at inns in Meisenheim.

Religion

Meisenheim’s Evangelical Christians belong, as one of the church’s southernmost communities, to the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland, while the Catholics belong to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Trier. As at 30 November 2013, there are 2,764 full-time residents in Meisenheim, and of those, 1,739 are Evangelical (62.916%), 591 are Catholic (21.382%), 8 are Lutheran (0.289%), 1 belongs to the New Apostolic Church (0.036%), 41 (1.483%) belong to other religious groups and 384 (13.893%) either have no religion or will not reveal their religious affiliation.[7]

Politics

Town council

The council is made up of 20 council members, who were elected by proportional representation at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman. The municipal election held on 7 June 2009 yielded the following results:[8]

| SPD | CDU | FDP | GRÜNE | FWG | Total | |

| 2009 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 20 seats |

| 2004 | 5 | 5 | – | 3 | 7 | 20 seats |

Mayor

Meisenheim’s mayor is Werner Keym.[9]

Coat of arms

The town’s arms might be described thus: Per fess argent a demilion azure armed and langued gules and crowned Or, and gules a blue tit proper.

The charge in the upper field, the lion, is a reference to the town’s former allegiance to the Counts of Veldenz, while the one in the lower field, the blue tit, is a canting charge for the town’s name, Meise being the German word for “tit”. This, however, is not actually the name’s derivation. Meisenheim was raised to town in 1315 by King Ludwig IV. From the 12th century onwards, the town was held by the Counts of Veldenz. The arms are based on the town’s first seal from the 14th century. It already bore the two charges that the current arms bear. In the 18th century, there was another composition in the town’s seal showing a lion above a bendy lozengy field (slanted diamond shapes of alternating tinctures) while the tit appeared on an inescutcheon. This change reflected a change in the lordship after the Counts of Veldenz died out in 1444 and were succeeded by the House of Wittelsbach, who bore arms bendy lozengy argent and azure (silver and blue). This pattern can still be seen in Bavaria’s coat of arms and flag today. The former arms, however, were reintroduced in 1935.[10] The article and the website Heraldry of the World show three different versions of the arms. The oldest, seen at Heraldry of the World, comes from the Coffee Hag albums from about 1925. It shows the tit in different tinctures, namely argent and sable (silver and black). The arms with the Wittelsbach bendy lozengy pattern are not shown.

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[11]

- Altstadt (“Old Town”) (monumental zone) – Old Town with building begun in the 14th century within and including the 14th-century town wall, the Gießen (arm of the Glan, possibly an old millrace) with the tanning houses as well as the building before the former Obertor (“Upper Gate”) and Schlosskirche (“Palace Church”) (see also below)

- Former Powder Tower (Pulverturm also called Bürgerturm) – round town wall corner tower, after 1315, later altered

- Evangelical Schlosskirche (“Palace Church”), Schlossplatz 1 – former Knights Hospitaller church, Late Gothic hall church, 1479–1504, architect Philipp von Gmünd, 1766–1770 interior conversion by Philipp Heinrich Hellermann; breast wall with Late Gothic portal, marked 1484 (see also below)

- Saint Anthony of Padua Catholic Parish Church (Pfarrkirche St. Antonius von Padua), Klenkertor 7 – former Franciscan monastery church: Baroque aisleless church, 1685–1688, architect Franz Matthias Heyliger, Baroque Revival tower, 1902, architect Ludwig Becker, Mainz (see also below)

- Town fortifications – long sections, partly with allure, of the town fortifications begun before 1315, partly destroyed in 1689

- Am Herrenschlag – Eiserner Steg (“Iron Footbridge”); iron construction with segmental arches, 1893

- Am Herrenschlag 1 – Gelbes Haus (“Yellow House”), former Knights Hospitaller commandry; essentially from 1349 (?) or before 1489, conversion in early 18th century; stately timber-frame building with half-hip roof, towards the back a “shield gable” (that is, a gable that forms part of the façade). Furnishing; bridge to the Schlosskirche churchyard, estate gate complex

- Am Herrenschlag 2 – Late Baroque house, partly slated timber framing, marked 1765

- Am Untertor – Untertorbrücke (“Lower Gate Bridge”); three-arch sandstone bridge, possibly after 1784, put back in order after damage in 1811, widened in 1894

- Am Untertor – Untertor (“Lower Gate”); three-floor town gate, 13th century and later

- Am Wehr – town wall remnant with allure; 13th century and later

- Am Wehr 2 – Gründerzeit sandstone-block building with knee wall, Late Classicist façade, 1879

- Am Wehr 3 – former tanning house; quarrystone building, partly timber-frame, between 1768 and 1820

- Am Wehr 4 – former tanning house; essentially from the latter half of the 19th century

- Amtsgasse 1 – stately Baroque estate complex; building with hipped mansard roof, great barn, 1763–1765, architect Philipp Heinrich Hellermann (?)

- Amtsgasse 2 – former Amtsgericht; Late Classicist sandstone-block building, 1865/1866

- Amtsgasse 4 – plastered building with eaves facing the street, about 1822/1826

- Amtsgasse 5 – three-floor Classicist house, marked 1833

- Amtsgasse 7 – Classicist house, about 1822/1823

- Amtsgasse 11 – timber-frame house, partly solid, 1631

- Amtsgasse 13 – former Hunoltsteiner Hof; three-wing complex, 16th to 18th centuries; main wing, partly timber-frame, 16th century, Baroque side building, 1791–1721, timber-frame building above a columned hall

- Amtsgasse 15 – Late Baroque house, marked 1752

- Amtsgasse 19 – Late Baroque house, marked 1778; essentially possibly from the 17th century

- An der Bleiche – sandstone arch bridge, latter half of the 19th century

- Bismarckplatz 1 – railway station; Late Historicist sandstone-block building with tower, goods shed, side building, 1894

- At Hammelsgasse 1 – Late Baroque door leaf, late 18th century

- Hammelsgasse 3 – house, essentially before 1726, marked 1833

- Hammelsgasse 5 – Baroque timber-frame house, before 1739

- Hans-Franck-Straße – one-arch quarrystone bridge, marked 1761

- Herzog-Wolfgang-Straße 9 – former agricultural school; Neoclassical plastered building, marked 1922/1923

- Hinter der Hofstatt 9 – clinker brick building, Art Nouveau motifs, 1904

- At Hinter der Hofstatt 11 – Classicist summer house, about 1830

- Klenkertor 2 – Late Baroque building with hipped mansard roof, marked 1784, essentially possibly after 1686

- Klenkertor 3 – shophouse, partly timber-frame, marked 1604, conversion in the late 18th century

- Klenkertor 6 – inn „Zum Engel“; stately timber-frame building, possibly from the early 18th century

- Klenkertor 7 – Catholic rectory; former Franciscan monastery, Baroque two-wing complex, marked 1716 and 1732, former monastery garden

- Klenkertor 9 – inn with dwelling; two Baroque timber-frame houses with gables facing the street, partly solid, 1704 and 1714, joined in 1818

- Klenkertor 16 – timber-frame house, partly solid, possibly from the 16th or 17th century

- Klenkertor 20 – quarrystone barn, before 1768, conversion marked 1853

- Klenkertor 26 – rich three-floor timber-frame house, marked 1618 and 1814

- Klenkertor 30 – house, possibly from the 17th century and later

- Klenkertor 36 – post-Baroque building with half-hip roof, 1822

- Lauergasse 3 – Late Baroque house, marked 1770, essentially possibly older

- Lauergasse 5 – Baroque house, marked 1739

- Lauergasse 8 – Baroque house, essentially possibly from the early 18th century

- Liebfrauenberg – sculpture group mother and child, 1937/1938, sculptor Arno Breker

- Lindenallee 2 – Late Classicist house with knee wall, 1843

- Lindenallee 9 – school, Heimatstil building with Renaissance motifs, 1908, Building Councillor Häuser, Kreuznach (see also below)

- Lindenallee 21 – stately Late Historicist villa, 1911

- Marktgasse 2 – Baroque timber-frame house, before 1761, conversion 1782

- Marktgasse 3 – timber-frame house, partly solid, essentially possibly from the 16th century, conversion marked 1809

- Marktgasse 5/7 – Classicist house, about 1830, essentially possibly from the 17th or 18th century

- Marktgasse 9 – three-floor Late Baroque house, marked 1782

- Marktplatz 2 – Mohren-Apotheke (pharmacy); three-floor Renaissance building, essentially from the 16th century

- Marktplatz 3 – three-floor shophouse, essentially from the 16th century (?), conversion 1841

- Marktplatz 4 – former market hall; long rich building with pitched roof, timber-frame, columned portico, possibly about 1550/1560 or from the 17th century

- Marktplatz 5 – Late Classicist sandstone-block building, 1856

- Mühlgasse 3 – former town mill; town wall tower/mill tower, great building with half-hip roof, essentially from the late 18th century, conversion marked 1860; three- to four-floor storage building, Rundbogenstil, 1897, with town wall tower, 14th century, wall remnants

- Mühlgasse 6 – Baroque timber-frame house, plastered, marked 1705

- Mühlgasse 8 – former stable (?), partly timber-frame, 18th century (?)

- Mühlgasse 10 – barn, partly timber-frame, 18th/19th century

- Mühlgasse 12 – house, essentially 1565 (?), timber-frame upper floor possibly from the 18th century

- Mühlgasse 14 – former hospital; plastered building, before 1768, conversions in the 19th and 20th centuries, barn 1706

- Obergasse 1 – Late Classicist house, marked 1852, essentially possibly older

- Obergasse 2 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, marked 1720

- Obergasse 3 – Kellenbacher Hof (estate); Late Gothic solid building with box oriel window and staircase tower, marked 1530

- Obergasse 4 – so-called Ritterherberge (“Knights’ Hostel”); two- to three-floor pair of semi-detached houses, partly timber-frame (Baroque), essentially from the latter half of the 16th century; marked 1723

- Obergasse 5 – Steinkallenfelser Hof (estate); Late Gothic solid building with staircase tower, about 1530, in 18th and 19th centuries made over

- Obergasse 6 – pair of semi-detached houses, partly timber-frame, essentially Late Gothic (15th/16th century), façade made over in Classicist style about 1840

- Obergasse 7 – former Reformed rectory; Late Baroque building, about 1760, timber-frame barn

- Obergasse 8 – Fürstenwärther Hof (estate); 16th century; three-floor house, Late Classicist façade, 1855, Master Builder Krausch, side building 18th and 19th centuries

- Obergasse 12 – Late Baroque house, before 1768

- Obergasse 13 – Baroque timber-frame house, plastered, 1713, converted before 1823

- Obergasse 15 – Baroque timber-frame house, 17th or early 18th century

- Obergasse 16 – house, partly slated timber-frame, essentially before 1730, conversion in the early 19th century; hind wing on Marktgasse (“Market Lane”): timber-frame house, partly solid, essentially from the 17th century, conversion about 1800

- Obergasse 17 – Renaissance timber-frame house, 16th century

- Obergasse 18 – former mikveh; Art Nouveau house door

- Obergasse 19 – so-called Inspektorenhaus (“Inspector’s House”); former Lutheran rectory, Renaissance timber-frame building with polygonal staircase tower, after 1588

- Obergasse 21 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, marked 1728

- Obergasse 22 – Late Gründerzeit house, clinker brick façade, 1906–1908, Master Builder Wilhelm

- Obergasse 23 – timber-frame house, partly solid, essentially possibly from the 17th century, Late Baroque conversion (1764?)

- Obergasse 25 – house with reliefs on windowsills, marked 1931

- Obergasse 26 – Boos von Waldeck’scher Hof (estate); essentially from the Late Middle Ages; three-floor plastered building, staircase tower, marked 1669, conversion 1822

- Obergasse 29 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, 17th century

- Obergasse 31 – house, marked 1612, essentially possibly Gothic (13th or 14th century?), conversion 1891, addition, partly timber-frame, about 1900

- Obergasse 33 – inn „Zur Blume“; Late Baroque building with mansard roof, before 1768

- At Obergasse 35 – Gothic window and corbels

- Obergasse 41 – three-floor Baroque timber-frame house, about 1704

- Obertor 13 – Art Nouveau villa, 1906/1907

- Obertor 15 – former Bonnet brewery; whole rambling complex of Gründerzeit buildings with former malt house and storage building with four chimneys, commercial yard, Gothic Revival style elements, last third of the 19th century

- Obertor 24 – villa; Late Gründerzeit building with hip roof, Renaissance Revival, three-floor tower, 1890–1893, architect Jean Rheinstädter, Kreuznach

- Obertor 30 – former forester’s house; one-floor Late Gründerzeit building with half-hip roof, 1898

- Obertor 34 – Late Gründerzeit villa, 1896/1897

- Obertor 36 – Historicized villa, 1906

- Obertor 38 – villa, Historicized Art Nouveau, 1906

- Rapportierplatz – running well, 1938, fountain bowl and post by Jordan, bronze figure by Emil Cauer the Younger

- Rapportierplatz 4 – inn with dwelling, timber-frame house, partly solid, essentially from the late 16th century, in 1754 described as made over in Baroque

- At Rapportierplatz 5 – portal, Baroque, marked 1718

- Rapportierplatz 6 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, 17th century, marked 1758

- Rapportierplatz 7 – Late Baroque building with mansard roof, mid 18th century

- Rapportierplatz 8 – three-floor timber-frame house, plastered, earlier half of the 19th century

- Rapportierplatz 12/14 – three-floor Late Baroque house with knee wall, before 1768, conversion 1870

- Rathausgasse 1 – former Lutheran Christianskirche (church); Late Baroque building with hip roof, 1761–1771, architect Philipp Heinrich Hellermann

- Rathausgasse 3 – former barn, partly timber-frame, before 1550 (apparently 1495)

- Rathausgasse 7, 9 – house, barn, mainly Baroque group of buildings, 18th century, building with half-hip roof, gateway with timber-frame superstructure, quarrystone side building

- Rathausgasse 8 – house, essentially possibly Late Gothic (16th century?), made over in the 18th century, about 1820 and in the 20th century; stately timber-frame side building

- Rathausgasse 10 – Baroque building with hipped mansard roof, 18th century

- Raumbacher Straße, Alter Friedhof (“Old Graveyard”) (monumental zone) – laid out before 1829; gravestones from the 17th century to about 1900; surrounding wall

- Raumbacher Straße 3 – house, Art Nouveau, 1906, architect Wilhelm

- Raumbacher Straße 5 – bungalow, Art Nouveau motifs, 1906/1907

- Raumbacher Straße 7/7a – one-and-a-half-floor pair of semi-detached houses, 1905

- Raumbacher Straße 9/11 – pair of semi-detached houses; bungalow with mansard roof, Art Nouveau, 1907/1908

- Behind Saarstraße 3 – summer house, Rococo, 1766

- Saarstraße 3A – former synagogue; three-floor sandstone-block building, Rundbogenstil, 1866 (see also below)

- Saarstraße 6 – stately Late Classicist complex with single roof ridge, about 1840

- Saarstraße 7 – leprosarium’s former chapel (?); marked 1745, made over about 1900; Late Classicist house, about 1850/1860, belonging to it?

- Saarstraße 9 – villa, Renaissance Revival, 1893

- Saarstraße 12 – post office; Heimatstil building with Expressionistic motifs, 1933, Postal Building Councillor Lütje

- Saarstraße 16 – shophouse, three-floor Late Gründerzeit house, Renaissance motifs, 1898

- Saarstraße 17 – villalike Late Historicist house, 1908–1910

- Saarstraße 21 – former bank building; Late Gründerzeit house, Renaissance motifs, 1901/1902, garden architect Karl Gréus, carried out by architect Schöpper

- Saarstraße 23 – Late Gründerzeit inn, Renaissance motifs, 1904

- Inside Schillerstraße 4 – two Classicist doors, stairway

- Schillerstraße 6 – former oilmill; Baroque timber-frame house, half-hip roof, 1693

- Schillerstraße 8 – Late Gründerzeit house, Renaissance Revival, 1902

- Schillerstraße 18 – former saddler’s shop (?); one-floor workshop building with shop about 1900

- Schlossplatz – on the town wall a relief of a warriors’ memorial 1914-1918, angel with trumpet, terracotta, sandstone, 1924, sculptor Robert Cauer the Younger

- Schlossplatz 3 – former palace of the Dukes of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, Magdalenenbau (“Magdalene Building”) of the former palace; eight-sided staircase tower, 1614, architect Hans Grawlich, floor added in 1825; side wing, 1825, architect Georg Moller (see also below)

- Schmidtsgasse 1 – three-floor timber-frame house, plastered, essentially from the 16th or early 17th century, conversion 1885

- Schmidtsgasse 2 – one-and-a-half-floor magazine building, 1876

- Schweinsgasse 7 – house with knee wall, essentially possibly from the 18th century, made over in Late Classicist style about 1830

- At Schweinsgasse 12 – Classicist house door leaf, earlier half of the 19th century

- Schweinsgasse 14 – former barn, essentially before 1768

- Schweinsgasse 16 – house, 1905

- Near Stadtgraben 7 – Classicist summer house, about 1820

- Near Stadtgraben 9 – Classicist summer house, marked 1836

- Untergasse 1 – Baroque timber-frame house, plastered and slated, possibly from the 17th century, marked 1716

- Untergasse 2 – three-floor building with half-hip roof, essentially from the 15th century, west eaves side from the 17th and 18th centuries

- Untergasse 8 – three-floor shophouse, timber-frame, essentially possibly from the latter half of the 16th century, possibly made over in the 18th century

- Untergasse 10 – Baroque shophouse, marked 1724

- Untergasse 12 – timber-frame house, partly solid, mid 16th century, Baroque makeover in the 17th century

- Untergasse 15/17 – shophouse, marked 1658, made over in the 19th century, shop built in about 1900

- Untergasse 18 – shophouse; three-floor Late Classicist sandstone-block building, 1872; belonging thereto Late Classicist house, mid 19th century

- Untergasse 19 – timber-frame house, partly solid, marked 1529, Baroque makeover in the later 18th century

- Untergasse 20/22 – three-floor shophouse (pair of timber-frame semi-detached houses), essentially before 1768; volute stone with mason’s mark, possibly 16th or 17th century

- Untergasse 23 – former town hall; three-floor Late Gothic building with half-hip roof, partly slated timber framing, hall ground floor, about 1517, architect possibly Philipp von Gmünd; staircase tower 1580, newel 1652

- Untergasse 24 – shophouse façade, building with hipped mansard roof, essentially before 1768, floor added about 1825

- Untergasse 28 – three-floor shophouse; timber-frame, essentially from the earlier half of the 16th century

- At Untergasse 29 – former house door and closet, 1797

- Untergasse 32 – three-floor Late Baroque house, formerly marked 1787

- Untergasse 33 – three-floor shophouse, late 17th century

- Untergasse 34 – shophouse, timber-frame house with box oriel window, apparently from 1526, possibly rather from the latter half of the 16th or early 17th century

- Untergasse 35 – three-floor shophouse; timber-frame, essentially before 1768, conversion in the 19th century

- Untergasse 36/38 – shophouse; no. 36: essentially from the late 18th century, Classicist shop built in; no. 38: 1932, architect Wilhelm

- At Untergasse 37 – house door; Rococo door leaf, about 1780

- At Untergasse 39 – Classicist door leaves, about 1820; stone tablet with builder’s inscription, 1817; wooden stairway, 1817

- Untergasse 40 – three-floor Classicist house, 1822/1823

- Untergasse 53 – three-floor shophouse, timber-frame, early 17th century

- Untergasse 54 – three-floor timber-frame house, partly solid, polygonal staircase tower, about 1570/1580, portal marked 1775

- Untergasse 55/57 – three-floor shophouse; two timber-frame houses combined under one roof, 16th century

- Untergasse 56 – Baroque shophouse, 17th or 18th century

- Untergasse 59 – timber-frame shophouse, partly solid, essentially possibly from the 18th century, conversion 1838

- Untergasse 60 – shophouse, marked 1820; Baroque hind wing, 18th century

- Untergasse 62 – three-floor shophouse, essentially from the 15th century (?), timber-frame possibly from the 18th century

- Untergasse 66 – inn „Zum Untertor“ (“At the Lower Gate”); Baroque inn with dwelling, before 1768 (possibly from the 17th century)

- Wagnergasse 1 – Classicist house, essentially about 1800

- Wagnergasse 2 – Baroque house, before 1712

- Wagnergasse 5 – timber-frame house, essentially before 1685, marked 1772

- Wagnergasse 8 – former postal station; timber-frame house, partly solid, marked 1671, made over in Late Baroque marked 1780

- Wagnergasse 11 – Late Classicist house, mid 19th century

- Wagnergasse 13 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, 17th or 18th century

- Wagnergasse 20 – Baroque timber-frame house, partly solid, mansard roof, marked 1743

- Bridge, in the valley of the Glan – two-arch Baroque sandstone bridge, marked 1749

- Summer house, Obern Klink – Late Baroque plastered building with upswept roof, 1766

- Summer house, Im Bendstich – Late Baroque plastered building, apparently from 1793

- Jewish graveyard, east of the Meisenheim–Rehborn road (monumental zone) – opened early in the 18th century, expanded in 1850, some 150 gravestones

- Water cistern, on Kreisstraße 6 – sandstone-block front, marked 1899

More about buildings

Old Town

Meisenheim’s Old Town is the only one in the area that can boast of continuous development, uninterrupted by war, fire or other destruction, since the 14th century. It also has an in places well preserved girding wall with a still preserved town gate, the Untertor (“Lower Gate”), the 1517 town hall, many noble estates and townsmen’s buildings as well as a mediaeval scale for weighing freight carts. The town’s oldest noble estate, the Boos von Waldeckscher Hof, was built about 1400. The building is today livened up by an event venue and can be visited.

Palatial residence

Left over from the Schloss (palatial residence), formerly held by the Counts of Veldenz and later the Dukes of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, extensively renovated in the 15th century but beset with fire in the 18th century and a round of demolition in the 19th, is only one major building, the Magdalenenbau, which was built in 1614 as a residence for Magdalena, the Ducal Zweibrücken widow, and considerably remodelled in the 19th century by the Landgraves of Hesse-Homburg. It is nowadays used by the Evangelical Church and hence also bears the name Herzog-Wolfgang-Haus (“Duke Wolfgang House”) after the Duke who lent the Reformation considerable favour.

Palace Church

The Evangelical Schlosskirche (“Palace Church”), a three-naved hall church, was built between 1479 and 1504. At the time of building, it stood right next to the Schloss and was the estate church, the town parish church and the Knights Hospitaller commandry’s church. Its Late Gothic west tower is shaped by rich stonemasonry. In the grave chapel, the 44 mostly Renaissance-style tombs of the House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken and the rich Gothic rib vaulting bear witness to sculptors’ highly developed art; also often praised is the wooden Rococo pulpit. The organ restored in 1993/1994 on the west gallery with its Baroque console was completed in 1767 by the renowned Brothers Stumm, and was already at the time, with its 29 stops, 2 manuals and pedal, one of the most opulent works of organ building in the Middle Rhine region. Together with the organ at the Augustinian Church (Augustinerkirche) in Mainz, it is one of the biggest preserved instruments built by this Hunsrück organ-building family.

Catholic church

The Baroque Catholic parish church, Saint Anthony of Padua, has very lovely interior décor, parts of which were endowed by former Polish king Stanisław Leszczyński, who for a time during his exile lived in Meisenheim.

Former school

On Lindenallee, which was fully renovated amid great controversy in 2007, stands the stately old Volksschule (public school), which after serving 90 years as a school is now an “adventure hotel”.

Former synagogue

At first, there was a Jewish prayer room. In 1808, a synagogue was built on Lauergasse. After it grew too small to serve the burgeoning Jewish community in the 19th century, the community decided in 1860 to build a new synagogue at the town’s bleachfield on what is now called Saarstraße. From the earliest time during which donations were being gathered comes a report from the magazine Der Israelitische Volkslehrer published in October 1860:

Meisenheim. This time, the local community has celebrated a very nice matnat yad. After using considerable sums to expand and beautify the graveyard two years ago, and one year ago, for the rabbi’s maintenance, correspondingly voting for a payrise for him, it granted over the last few festive days the sum of 2,000 Rhenish guilders to build a new synagogue. The one used until now was at the time of its founding 52 years ago was reckoned on a much smaller membership and even about 12 years ago became bereft of light as its neighbouring properties on all sides were built up; so that, seen from the point of view of the demands for better taste, it lacked light, air and room. Anyone who knows the local community’s circumstances will not consider this willingness to make sacrifices slight and will not refuse the community’s goodwill the fullest approval. Of course, this sum is still not enough and it is hoped all the more that there will be outside help, as people here never stood idly by when a call for help came from outside.

The earlier synagogue was torn down a few years later. The new building was to become a representative building. The financing – costs reached 15,200 Rhenish guilders – could be ensured with a bit of effort. On 3 August 1866, the consecration of the new synagogue, designed by architect Heinrich Krausch, took place. It had seating for 160 worshippers. It was equipped with, among other things, six Torah scrolls, elaborate Torah ornamentation, silver candlesticks, an organ and a library. The prayer books were kept in six lecterns. Outwardly, it was a six-axis aisleless building with a three-floor façade with twin towers. On Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938), the Meisenheim synagogue sustained considerable damage. All doors, windows and great parts of the galleries were reduced to rubble and a fire was set, although this was quickly quenched once the Brownshirt thugs realized that one of the neighbouring buildings was an SA house. The synagogue, however, was not torn down as so many others were, although the upper levels of the twin towers were removed in 1940. In the time of the Second World War, the building was mainly used as an industrial works, quite contrary to its originally intended purpose, and thereafter as a municipal storehouse. From 1951 on, it was a private storehouse for grain, fodder and fertilizer. In a conversion, the remnants of the women’s galleries were torn out, the windows were walled up and upper floors were built inside. In 1982, the building was placed under monumental protection. In 1985, the Meisenheim Synagogue Sponsorship and Promotional Association was founded, which acquired the former synagogue the following year and had it restored. On 9 November 1988 – fifty years to the day after Kristallnacht – the former synagogue building was opened to the public as the Haus der Begegnung (“House of Meeting”). This new name corresponds to the literal meaning of the Hebrew term for “synagogue”: בית כנסת (beyt knesset, literally “house of assembly”). On the upper floor, as a visible reminder of the former synagogue, a glass window by the Israeli artist Ruth van de Garde-Tichauer was installed. The window was created with technical assistance from Karl-Heinz Brust from Kirn. The window’s content is the return of the Twelve Tribes of Israel to Jerusalem based on the text from the Amidah (תפילת העמידה; Tefilat HaAmidah “The Standing Prayer”), also called the Shmoneh Esreh (שמנה עשרה; “The Eighteen”): “Sound the great shofar for our freedom; raise a banner to gather our exiles, and bring us together from the four corners of the earth into our land.”[12] In a decision taken on 21 May 1997, the synagogue building received the protection of the Hague Convention as a cultural property especially worthy of protection. Since 1999, above the entrance, has been a Star of David made of Jerusalem limestone, endowed by the Bad Kreuznach district’s partner town in Israel, Kiryat Motzkin. The former synagogue’s address in Meisenheim is Saarstraße 3.[13]

Jewish graveyard

The Jewish graveyard in Meisenheim was laid out no later than the early 18th century. The oldest preserved gravestone dates from 1725. In 1859, the graveyard was expanded with the addition of the “newer part”. The last burial that took place there was in 1938 (Felix Kaufmann). The graveyard has an area of 4 167 m². In the graveyard’s “older part”, gravestones are still standing at 105 of the graves, and in the “newer part”, this is so for a further 125 graves. The “newer part” is bordered on the east by a quarrystone wall. There is a great wrought-iron entrance gate. The graveyard lies outside the town to the east, east of the road from Meisenheim to Rehborn, in a wood called the “Bauwald”. It can be reached by walking about 200 m along a farm lane that branches off the highway.[14]

Regular events

- Mai'n Sonntag (shops open on Sunday), each year on the third Sunday in May

- Heimbacher Brunnenfest, folk festival on the first weekend in July

- Wasserfest (“Water Festival”), staged by the volunteer fire brigade

- Mantelsonntag (shops open on Sunday), each year on the third Sunday in October

- Weihnachtsmarkt (“Christmas Market”, with craft presentation at town hall)

Economy and infrastructure

Transport

In 1896, Meisenheim was joined to the railway network with the opening of the Lauterecken–Odernheim stretch of the Lauter Valley Railway. This section was absorbed in 1904 into the Glantalbahn, which was fully opened that year. Meisenheim’s railway station was important to all resident industry. In 1986, though, passenger service between Lauterecken-Grumbach and Staudernheim was discontinued. Today, the station is only used as a stop on the adventure draisine journeys between Staudernheim and Kusel. Snaking through Meisenheim, mostly along the town’s outskirts, is Bundesstraße 420.

Schools

Meisenheim has three schools:

- Astrid-Lindgren-Grundschule (primary school)

- Realschule plus in integrative form.

- Paul-Schneider-Gymnasium, an extensive complex built in 1953 with adjoining boarding school, built as a successor to the town’s former Progymnasium, the “Latin school”, which stood at the now likewise vanished Obertor (“Upper Gate”)

Healthcare

The Glantal-Klinik Meisenheim has two hospitals at its disposal. The Haus „Hinter der Hofstadt“ covers the demand for surgery, internal medicine and ambulant family medicine. The Glantal-Klinik is a centre for acute neurology, neurological rehabilitation, surgery and accident surgery, internal medicine and communication disorder therapy. Adjoining the clinic is a speech-language pathology centre.

Famous people

Sons and daughters of the town

- Carl von Coerper (1854–1942), admiral and naval attaché

- Heinrich Coerper (1863–1936), clergyman, founder of the Liebenzell Mission

- Friedrich Karl von Fürstenwärther (1769–1856), Austrian field marshal-lieutenant and baron, from the House of Wittelsbach

- Leopold von Fürstenwärther (1769–1839), Bavarian officer and baron, from the House of Wittelsbach

- Friedrich (Pfalz-Zweibrücken-Vohenstrauß-Parkstein)|Friedrich von Pfalz-Vohenstrauß-Parkstein (1557–1597), Duke of Palatinate-Parkstein

- Karl Koehl (1847–1929), doctor and prehistorian, pioneer of Stone Age and Bronze Age research

- Marco Reich (1977–), footballer

- Melitta Sundström (1964–1993); actually Thomas Gerards, entertainer

Famous people associated with the town

- Stanisław Leszczyński (b. 20 October 1677 in Lwów, Poland [now Lviv, Ukraine]; d. 23 February 1766 in Lunéville, France) — King of Poland; between 1714 and 1718 often in Meisenheim

- Ferdinand Heinrich Friedrich von Hessen-Homburg (b. 26 April 1783 in Homburg vor der Höhe; d. 24 March 1866 in Homburg vor der Höhe) — Last Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg

- Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom (b. 22 May 1770 in London; d. 10 January 1840 in Frankfurt) — also Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg; lady of the house at the Magdalenenbau (“Magdalene Building”) of the former palace

- Friedrich VI, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg (b. 30 July 1769 in Homburg vor der Höhe; d. 2 April 1829 in Homburg vor der Höhe) — lord of the house at the Magdalenenbau of the former palace

- Georg Moller (b. 21 January 1784 in Diepholz; d. 13 March 1852 in Darmstadt) — architect and town planner, responsible for, among other things, the Magdalenenbau

- Johann Georg Martin Reinhardt (1794–1872), chairman of the Oberamt/district of Meisenheim from 1832 to 1872

- Johann Christoph Beysiegel (1778–1843), goldsmith and silversmith as well as first lieutenant in the Landwehr (1819).[15]

- Hellmut von Schweinitz (1901-1960), writer and journalist, clergyman at the Evangelical Schlosskirche, 1947-1960, founder of the Meisenheimer Dichterwochen (“poet weeks”)

-

Stanisław Leszczyński

-

Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom and Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg

-

Friedrich VI, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg

-

Georg Moller

Further reading

- Der „historische Stadtrundgang“. In: Meisenheim am Glan. (24 S.), (Hrsg.: Stadt Meisenheim am Glan), Seite 1-11

- Werner Vogt: Meisenheim am Glan als Zweitresidenz der Wittelsbacher Herzöge und Pfalzgrafen von Zweibrücken. In: Jahrbuch für westdeutsche Landesgeschichte. 19, 1993, Seite 303-324.

References

- ↑ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden am 31.12.2012". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). 2013.

- ↑ Area

- ↑ Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz – Amtliches Verzeichnis der Gemeinden und Gemeindeteile, Seite 16 (PDF; 2,2 MB)

- ↑ Falsified documents

- ↑ Jewish history

- ↑ Peter Bayerlein: Schinderhannes-Ortslexikon, S. 157, Mainz-Kostheim 2003

- ↑ Religion

- ↑ Der Landeswahlleiter Rheinland-Pfalz: Kommunalwahl 2009, Stadt- und Gemeinderatswahlen

- ↑ Meisenheim’s mayor

- ↑ Description and explanation of Meisenheim’s arms

- ↑ Directory of Cultural Monuments in Bad Kreuznach district

- ↑ English translation from Amidah

- ↑ Former synagogue

- ↑ Jewish graveyard

- ↑ Scheffler, Wolfgang. „Johann Christoph Beysiegel.“ Goldschmiede Rheinland-Westfalens: Daten, Werke, Zeichen. Vol. 2. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1973. 740.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meisenheim. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Meisenheim in the collective municipality’s webpages (German)

- Information about Meisenheim’s Jewish history with photos of the former synagogue (German)