Megaponera

| Megaponera analis | |

|---|---|

| |

| A major worker guarding a cocoon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Ponerinae |

| Tribe: | Ponerini |

| Genus: | Megaponera |

| Species: | M. analis |

| Binomial name | |

| Megaponera analis (Latreille, 1802) | |

| |

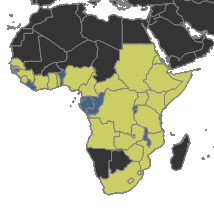

| Distribution in Africa (Green: present; blue: likely present; black: absent) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Megaponera foetens (Fabricius, 1793) Pachycondyla analis (Latreille, 1802) | |

Megaponera analis is the sole species of the genus Megaponera.[1] They are a strictly termite-eating (termitophagous) ponerine ant species widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa[2] and most commonly known for their column-like raiding formation when attacking termite feeding sites. Their sophisticated raiding behaviour gave them the common name Matabele ant after the Matabele tribe, fierce warriors who overwhelmed various other tribes during the 1800s.[3] At nearly 20 millimetres (0.79 in) in length, M. analis is one of the world's largest ants.[4][5]

Taxonomy

Megaponera is a genus of ponerine ant first defined by Gustav Mayr in 1862 for Formica analis[6] (Latreille, 1802), the sole species belonging to the genus to date. In 1994 William L. Brown, Jr. synonymised the genus under Pachycondyla even though he lacked phylogenetic justification, thereby changing the name from Megaponera foetens to Pachycondyla analis.[7] In 2014 Schmidt and Shattuck revived Megaponera back to full genus status due to both molecular and morphological evidence. Since foetens was just a specific epithet incorrectly used throughout the literature the new name for the species as of June 2014 is Megaponera analis.[1]

Subspecies of Megaponera analis

Due to its very wide distribution throughout Africa, it is likely that there are many more subspecies of M. analis than those recognised at the moment – some of which may warrant elevation to full species status.

The five currently recognised subspecies of M. analis are:[1]

- M. analis amazon (Santschi, 1935): Ethiopia

- M. analis crassicornis (Gerstäcker, 1859): Mozambique

- M. analis rapax (Santschi, 1914b): Tanzania

- M. analis subpilosa (Santschi, 1937): Angola

- M. analis termitivora (Santschi, 1930): Democratic Republic of the Congo

Morphology

The size of worker ants varies between 5–18 millimetres (0.20–0.71 in), with larger workers making up to 50 percent of the colony.[8] Though it was often suggested that the larger ants also function as gamergates,[9] they were never observed laying fertile eggs, a function solely reserved to the ergatoid queen.[5] Even though M. analis is often referred to as dimorphic, with a major and minor caste, they actually exhibit polyphasic allometry in worker sizes. The variations among the ants are mostly in size and pubescence (with minors having less), although differences in the mandibles have also been observed, with minors having smoother mandibles compared to majors.[4]

Range and habitat

Megaponera analis occurs throughout sub-Saharan Africa from 25° S to 12° N.[2] Its nests are generally subterranean, up to 0.7 metres (2 ft 4 in) deep, and often located next to trees, rocks, or abandoned termite hills.[10] While the nest itself may have more than one entrance, it comprises only one chamber in which the eggs, larvae, cocoons, and the queen are located.[11]

Behaviour

Raiding behaviour

The raiding activity of M. analis focuses on dawn and dusk between 6:00–10:00 and 15:00–19:00,[11][12] with approximately three to five raids occurring per day. There are also observations of a third raiding activity window during the night between 22:00–2:00, although this phase has been poorly studied.[10] Megaponera analis raids focus solely on termites from the subfamily Macrotermitinae and generally consist of 200 to 500 ants.[8]

The general foraging pattern of M. analis starts with scout ants searching an area of approximately 50 m (160 ft) around the nest for termite foraging sites. This searching phase can last up to one hour, and if it is unsuccessful the scout returns to the nest by a circuitous route. If a scout ant finds a potential site, it will start to investigate it without getting into contact with the termites or entering the galleries, before returning by a direct route to recruit its nestmates to conduct a raid.[8]

Although the scout ant is observed to lay a pheromone trail on the return journey to the nest, the other ants seem to be unable to follow this trail without the help of the scout.[10] The scout ant therefore leads the raid from the front, with the other ants following in a column-like formation.[13] Recruitment time varies between 60 and 300 seconds, with all castes taking part in a raid. During the outward journey towards the termites, all ants are laying a pheromone trail, making it much easier for them to find their way back to the nest later without having to rely on the scout ant.[14]

Approximately 20–50 cm (7.9–19.7 in) before contact with the termites, the raiding column stops and agglomerates until all the ants in the column have arrived, forming a sort of circle around the raid leader (the scout). Afterwards the ants rush forward towards the termites in an open formation and overwhelm their prey. During the attack, a division of labour can be observed. While the majors focus mostly on breaking up the protective layer over the foraging galleries of the termites, the minors rush into the galleries to kill the termites through the created openings.[8] After a foraging site has been exploited, the ants congregate at the same place they waited earlier, with the majors carrying the termites, and return to the nest in a column-like formation. These raids are always a single event and ants do not return independently to re-exploit a former raiding site, although the possibility of the scout ant remembering a site and reinvestigating it in the future for a possible second raid cannot be excluded.[15]

Colony size and reproduction

Colony size varies, depending on the location and age of the colony, from 440 to 2300 adult ants.[4] Little is known about the reproduction of M. analis. The alate males of M. analis are often observed leaving and entering the nests of established colonies by using pheromone trails from previous raids as guides to the nest.[16] Since M. analis colonies are obligate termite hunters, it is impossible for a queen to establish a nest on her own, since she could not conduct a raid against termites without a standing army of worker ants. It is therefore assumed that when a new colony is created, it occurs through colony fission, with the new queen taking a number of the workers of the old colony with her to create a new colony.[5]

Cooperative self-defence

While cooperative defence of the nest is well known in ants,[5] cooperative self-defence outside of the nest is much less so. When M. analis ants are attacked by driver ants (Dorylus sp.) outside of the nest, they cooperate with one another in an attempt to defend themselves by checking each other's extremities for enemy ants and removing any that are clinging to their legs or antennae.[17]

Gallery

| Megaponera analis pictures from Comoé National Park, Ivory Coast | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Schmidt, C.A.; Shattuck, S. O. (18 June 2014). "The Higher Classification of the Ant Subfamily Ponerinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with a Review of Ponerine Ecology and Behavior". Zootaxa 3817 (1): 1–242. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3817.1.1. PMID 24943802.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wheeler, William Morton (1936). "Ecological Relations of Ponerine and Other Ants to Termites". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 71 (3): 159. doi:10.2307/20023221. JSTOR 20023221.

- ↑ Wilson, Edward O. (2014). A Window on Eternity: A Biologist’s Walk Through Gorongosa National Park. Simon & Schuster. p. 83. ISBN 978-1476747415.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Villet, Martin H. (1990). "Division of labour in the Matabele ant Megaponera foetens (Fabr.) (Hymenoptera Formicidae)". Ethology Ecology & Evolution 2 (4): 397–417. doi:10.1080/08927014.1990.9525400.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Hölldobler, Bert; Wilson, Edward O. (1990). The Ants. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674040755.

- ↑ Mayr, G. (1862). "Myrmecologische Studien". Verh. K-K. Zool.-Bot. Ges. Wien 12: 649–776 (page 714, Megaponera; (diagnosis in key) as genus; Megaponera in Ponerinae [Poneridae])

- ↑ Bolton, B. (1994). Identification guide to the ant genera of the world. Harvard University Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-674-44280-6.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Longhurst, C.; Howse, P. E. (1979). "Foraging, recruitment and emigration in Megaponera foetens (Fab.) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from the Nigerian Guinea Savanna". Insectes Sociaux 26 (3): 204–215. doi:10.1007/BF02223798.

- ↑ Crewe, R. M.; Peeters, C. P.; Villet, M. (1984). "Frequency distribution of worker sizes in Megaponera foetens". South African Journal of Zoology 19 (3): 247–248. ISSN 0254-1858.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Yusuf, Abdullahi A. (2010). Termite raiding by the ponerine ant Pachycondyla analis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) (Ph.D.). University of Pretoria.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lepage, M. G. (1981). "Étude de la prédation de Megaponera foetens (F.) sur les populations récoltantes de Macrotermitinae dans un ecosystème semi-aride (Kajiado-Kenya)". Insectes Sociaux 28 (3): 247–262. doi:10.1007/BF02223627.

- ↑ Levieux, Jean (1966). "Note préliminaire sur les colonnes de chasse de Megaponera fœtens F. (Hyménoptère Formicidæ)". Insectes Sociaux 13 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1007/BF02223567.

- ↑ Bayliss, J.; Fielding, A. (2002). "Termitophagous foraging by Pachycondyla analis (Formicidae, Ponerinae) in a Tanzanian coastal dry forest". Sociobiology 39: 103–122.

- ↑ Hölldobler, Bert; Braun, Ulrich; Gronenberg, Wulfila; Kirchner, Wolfgang H.; Peeters, Christian (1994). "Trail communication in the ant Megaponera foetens (Fabr.) (Formicidae, Ponerinae)". Journal of Insect Physiology 40 (7): 585–593. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(94)90145-7.

- ↑ Longhurst, C.; Baker, R.; Howse, P. E. (1979). "Termite predation by Megaponera foetens (FAB.) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Journal of Chemical Ecology 5 (5): 703–719. doi:10.1007/BF00986555.

- ↑ Longhurst, C.; Howse, P. E. (1979). "Some Aspects of the Biology of the Males of Megaponera Foetens (Fab.) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Insectes Sociaux 26 (2): 85–91. doi:10.1007/BF02223502.

- ↑ Beck, J.; Kunz, K. (2007). "Cooperative self-defence: Matabele ants (Pachycondyla analis) against African driver ants (Dorylus sp.; Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Myrmecological News 10: 27–28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Megaponera analis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Megaponera |

- Antweb: further information about M. analis

- Arkive: further information about M.analis

- Antwiki: further information about M.analis

- Ants of Africa: pictures and taxonomic information about M.analis

- AntCat: online catalog for the ants of the world

- Hymenoptera online: further taxonomic information

- Encyclopedia of Life