Megafauna

In terrestrial zoology, megafauna (Ancient Greek megas "large" + New Latin fauna "animal") are large or giant animals. The most common thresholds used are 45 kilograms (100 lb)[1][2] or 100 kilograms (220 lb).[2][3] This thus includes many species not popularly thought of as overly large, such as white-tailed deer, red kangaroo, and humans.

In practice, the most common usage encountered in academic and popular writing describes land animals roughly larger than a human that are not (solely) domesticated. The term is especially associated with the Pleistocene megafauna – the land animals often larger than modern counterparts considered archetypical of the last ice age, such as mammoths, the majority of which in northern Eurasia, the Americas and Australia became extinct as recently as 10,000–40,000 years ago.[4] It is also commonly used for the largest extant wild land animals, especially elephants, giraffes, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, and large bovines. Megafauna may be subcategorized by their trophic position into megaherbivores (e.g., elk), megacarnivores (e.g., lions), and, more rarely, megaomnivores (e.g., bears).

Other common uses are for giant aquatic species, especially whales, any larger wild or domesticated land animals such as larger antelope and cattle, as well as numerous dinosaurs and other extinct giant reptilians.

The term is also sometimes applied to animals (usually extinct) of great size relative to a more common or surviving type of the animal, for example the 1 m (3 ft) dragonflies of the Carboniferous period.

Ecological strategy

Megafauna – in the sense of the largest mammals and birds – are generally K-strategists, with high longevity, slow population growth rates, low mortality rates, and (at least for the largest) few or no natural predators capable of killing adults. These characteristics, although not exclusive to such megafauna, make them vulnerable to human overexploitation, in part because of their slow population recovery rates.

Evolution of large body size

One observation that has been made about the evolution of larger body size is that rapid rates of increase that are often seen over relatively short time intervals are not sustainable over much longer time periods. In an examination of mammal body mass changes over time, the maximum increase possible in a given time interval was found to scale with the interval length raised to the 0.25 power.[5] This is thought to reflect the emergence, during a trend of increasing maximum body size, of a series of anatomical, physiological, environmental, genetic and other constraints that must be overcome by evolutionary innovations before further size increases are possible. A strikingly faster rate of change was found for large decreases in body mass, such as may be associated with the phenomenon of insular dwarfism. When normalized to generation length, the maximum rate of body mass decrease was found to be over 30 times greater than the maximum rate of body mass increase for a ten-fold change.[5]

In terrestrial mammals

Subsequent to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that eliminated the non-avian dinosaurs about 66 Ma ago, terrestrial mammals underwent a nearly exponential increase in body size as they diversified to occupy the ecological niches left vacant.[6] Starting from just a few kg before the event, maximum size had reached ~50 kg a few million years later, and ~750 kg by the end of the Paleocene. This trend of increasing body mass appears to level off about 40 Ma ago (in the late Eocene), suggesting that physiological or ecological constraints had been reached, after an increase in body mass of over three orders of magnitude.[6] However, when considered from the standpoint of rate of size increase per generation, the exponential increase is found to have continued until the appearance of Indricotherium 30 Ma ago. (Since generation time scales with body mass0.259, increasing generation times with increasing size cause the log mass vs. time plot to curve downward from a linear fit.)[5]

Megaherbivores eventually attained a body mass of over 10 000 kg. The largest of these, indricotheres and proboscids, have been hindgut fermenters, which are believed to have an advantage over foregut fermenters in terms of being able to accelerate gastrointestinal transit in order to accommodate very large food intakes.[7] A similar trend emerges when rates of increase of maximum body mass per generation for different mammalian clades are compared (using rates averaged over macroevolutionary time scales). Among terrestrial mammals, the fastest rates of increase of body mass0.259 vs. time (in Ma) occurred in perissodactyls (a slope of 2.1), followed by rodents (1.2) and proboscids (1.1),[5] all of which are hindgut fermenters. The rate of increase for artiodactyls (0.74) was about a third that of perissodactyls. The rate for carnivorans (0.65) was slightly lower yet, while primates, perhaps constrained by their arboreal habits, had the lowest rate (0.39) among the mammalian groups studied.[5]

Terrestrial mammalian carnivores from several eutherian groups (the mesonychid Andrewsarchus, the creodonts Megistotherium and Sarkastodon, and the carnivorans Amphicyon and Arctodus) all reached a maximum size of about 1000 kg[6] (the carnivoran Arctotherium apparently actually got somewhat larger). The largest known metatherian carnivore, Proborhyaena gigantea, apparently reached 600 kg, also close to this limit.[8] A similar theoretical maximum size for mammalian carnivores has been predicted based on the metabolic rate of mammals, the energetic cost of obtaining prey, and the maximum estimated rate coefficient of prey intake.[9] It has also been suggested that maximum size for mammalian carnivores is constrained by the stress the humerus can withstand at top running speed.[8]

Analysis of the variation of maximum body size over the last 40 Ma suggests that decreasing temperature and increasing continental land area are associated with increasing maximum body size. The former correlation would be consistent with Bergmann's rule,[10] and might be related to the thermoregulatory advantage of large body mass in cool climates,[6] better ability of larger organisms to cope with seasonality in food supply,[10] or other factors;[10] the latter correlation could be explainable in terms of range and resource limitations.[6] However, the two parameters are interrelated (due to sea level drops accompanying increased glaciation), making the driver of the trends in maximum size more difficult to identify.[6]

In marine mammals

Since tetrapods (first reptiles, later mammals) returned to the sea in the Late Permian, they have dominated the top end of the marine body size range, due to the more efficient intake of oxygen possible using lungs.[11][12] The ancestors of cetaceans are believed to have been the semiaquatic pakicetids, no larger than wolves, of about 53 million years (Ma) ago.[13] By 40 Ma ago, cetaceans had attained a length of 20 m or more in Basilosaurus, an elongated, serpentine whale that differed from modern whales in many respects and was not ancestral to them. Following this, the evolution of large body size in cetaceans appears to have come to a temporary halt, and then to have backtracked, although the available fossil records are limited. However, in the period from 31 Ma ago (in the Oligocene) to the present, cetaceans underwent a significantly more rapid sustained increase in body mass (a rate of increase in body mass0.259 of a factor of 3.2 per million years) than achieved by any group of terrestrial mammals.[5] This trend led to the largest animal of all time, the modern blue whale. Several reasons for the more rapid evolution of large body size in cetaceans are possible. Fewer biomechanical constraints on increases in body size may be associated with suspension in water as opposed to standing against the force of gravity, and with swimming movements as opposed to terrestrial locomotion. Also, the greater heat capacity and thermal conductivity of water compared to air may increase the thermoregulatory advantage of large body size in marine endotherms, although diminishing returns apply.[5]

Cetaceans are not the only marine mammals to reach unprecedented size in the modern era. The largest carnivoran of all time is the mostly aquatic modern southern elephant seal.

In flightless birds

Because of the small initial size of all mammals following the extinction of the dinosaurs, nonmammalian vertebrates had a roughly ten-million-year-long window of opportunity (during the Paleocene) for evolution of gigantism without much competition.[14] During this interval, apex predator niches were often occupied by reptiles, such as terrestrial crocodilians (e.g. Pristichampsus), large snakes (e.g. Titanoboa) or varanid lizards, or by flightless birds[6] (e.g. Gastornis in Europe and North America, Paleopsilopterus in South America). This is also the period when flightless herbivorous paleognath birds evolved to large size on a number of Gondwanan land masses. These birds, termed ratites, have traditionally been viewed as representing a lineage separate from that of their small flighted relatives, the Neotropic tinamous. However, recent genetic studies have found that tinamous nest well within the ratite tree, and are the sister group of the extinct moa of New Zealand.[15][14][16] Similarly, the small kiwi of New Zealand have been found to be the sister group of the extinct elephant birds of Madagascar.[14] These findings indicate that flightlessness and gigantism arose independently multiple times among ratites via parallel evolution.

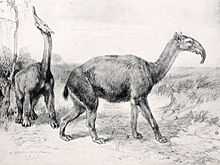

In the northern continents, large predatory birds were displaced when large eutherian carnivores evolved. In isolated South America, the phorusrhacids could not be outcompeted by the local metatherian sparassodonts and remained dominant until advanced eutherian predators arrived from North America (as part of the Great American Interchange) during the Pliocene. However, none of the largest predatory (Brontornis), possibly omnivorous (Dromornis[17]) or herbivorous (Aepyornis) flightless birds of the Cenozoic ever grew to masses much above 500 kg, and thus never attained the size of the largest mammalian carnivores, let alone that of the largest mammalian herbivores. It has been suggested that the increasing thickness of avian eggshells in proportion to egg mass with increasing egg size places an upper limit on the size of birds.[18][note 1] The largest species of Dromornis, D. stirtoni, may have gone extinct after it attained the maximum avian body mass and was then outcompeted by marsupial diprotodonts that evolved to sizes several times larger.[21]

Megafaunal mass extinctions

Timing and possible causes

A well-known mass extinction of megafauna, the Holocene extinction (see also Quaternary extinction event), occurred at the end of the last ice age glacial period (a.k.a. the Würm glaciation) and wiped out many giant ice age animals, such as woolly mammoths, in the Americas and northern Eurasia. Various theories have attributed the wave of extinctions to human hunting, climate change, disease, a putative extraterrestrial impact, or other causes. However, this extinction pulse near the end of the Pleistocene was just one of a series of megafaunal extinction pulses that have occurred during the last 50,000 years over much of the Earth's surface, with Africa and southern Asia (where the local megafauna had a chance to evolve alongside modern humans) being largely spared. The latter areas did suffer a gradual attrition of megafauna, particularly of the slower-moving species (a class of vulnerable megafauna epitomized by giant tortoises), over the last several million years.[22][23]

Outside the mainland of Afro-Eurasia, these megafaunal extinctions followed a highly distinctive landmass-by-landmass pattern that closely parallels the spread of humans into previously uninhabited regions of the world, and which shows no correlation with climatic history (which can be visualized with plots over recent geological time periods of climate markers such as marine oxygen isotopes or atmospheric carbon dioxide levels).[24][25] Australia was struck first around 45,000 years ago,[26] followed by Tasmania about 41,000 years ago (after formation of a land bridge to Australia about 43,000 years ago),[27][28][29] Japan apparently about 30,000 years ago,[30] North America 13,000 years ago, South America about 500 years later,[31][32] Cyprus 10,000 years ago,[33][34] the Antilles 6000 years ago,[35] New Caledonia[36] and nearby islands[37] 3000 years ago, Madagascar 2000 years ago,[38] New Zealand 700 years ago,[39] the Mascarenes 400 years ago,[40] and the Commander Islands 250 years ago.[41] Nearly all of the world's isolated islands could furnish similar examples of extinctions occurring shortly after the arrival of Homo sapiens, though most of these islands, such as the Hawaiian Islands, never had terrestrial megafauna, so their extinct fauna were smaller.[24][25]

An analysis of Sporormiella fungal spores (which derive mainly from the dung of megaherbivores) in swamp sediment cores spanning the last 130,000 years from Lynch's Crater in Queensland, Australia showed that the megafauna of that region virtually disappeared about 41,000 years ago, at a time when climate changes were minimal; the change was accompanied by an increase in charcoal, and was followed by a transition from rainforest to fire-tolerant sclerophyll vegetation. The high-resolution chronology of the changes supports the hypothesis that human hunting alone eliminated the megafauna, and that the subsequent change in flora was most likely a consequence of the elimination of browsers and an increase in fire.[42][43][44] The increase in fire lagged the disappearance of megafauna by about a century, and most likely resulted from accumulation of fuel once browsing stopped. Over the next several centuries grass increased; sclerophyll vegetation increased with a lag of another century, and a sclerophyll forest developed after about another thousand years.[44] During two periods of climate change about 120 and 75 thousand years ago, sclerophyll vegetation had also increased at the site in response to a shift to cooler, drier conditions; neither of these episodes had a significant impact on megafaunal abundance.[44] Similar conclusions regarding the culpability of human hunters in the disappearance of Pleistocene megafauna were obtained via an analysis of a large collection of eggshell fragments of the flightless Australian bird Genyornis newtoni[45] and from analysis of Sporormiella fungal spores from a lake in eastern North America.[46][47]

Continuing human hunting and environmental disturbance has led to additional megafaunal extinctions in the recent past, and has created a serious danger of further extinctions in the near future (see examples below).

A number of other mass extinctions occurred earlier in Earth's geologic history, in which some or all of the megafauna of the time also died out. Famously, in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event the dinosaurs and most other giant reptilians were eliminated. However, the earlier mass extinctions were more global and not so selective for megafauna; i.e., many species of other types, including plants, marine invertebrates[48] and plankton, went extinct as well. Thus, the earlier events must have been caused by more generalized types of disturbances to the biosphere.

Consequences of depletion of megafauna

Effect on nutrient transport

Megafauna play a significant role in the lateral transport of mineral nutrients in an ecosystem, tending to translocate them from areas of high to those of lower abundance. They do so by their movement between the time they consume the nutrient and the time they release it through elimination (or, to a much lesser extent, through decomposition after death).[49] In South America's Amazon Basin, it is estimated that such lateral diffusion was reduced over 98% following the megafaunal extinctions that occurred roughly 12,500 years ago.[50][51] Given that phosphorus availability is thought to limit productivity in much of the region, the decrease in its transport from the western part of the basin and from floodplains (both of which derive their supply from the uplift of the Andes) to other areas is thought to have significantly impacted the region's ecology, and the effects may not yet have reached their limits.[51]

Effect on methane emissions

Large populations of megaherbivores have the potential to contribute greatly to the atmospheric concentration of methane, which is an important greenhouse gas. Modern ruminant herbivores produce methane as a byproduct of foregut fermentation in digestion, and release it through belching. Today, around 20% of annual methane emissions come from livestock methane release. In the Mesozoic, it has been estimated that sauropods could have emitted 520 million tons of methane to the atmosphere annually,[52] contributing to the warmer climate of the time (up to 10 C warmer than at present).[52][53] This large emission follows from the enormous estimated biomass of sauropods, and because methane production of individual herbivores is believed to be almost proportional to their mass.[52]

Recent studies have indicated that the extinction of megafaunal herbivores may have caused a reduction in atmospheric methane. This hypothesis is relatively new.[54] One study examined the methane emissions from the bison that occupied the Great Plains of North America before contact with European settlers. The study estimated that the removal of the bison caused a decrease of as much as 2.2 million tons per year.[55] Another study examined the change in the methane concentration in the atmosphere at the end of the Pleistocene epoch after the extinction of megafauna in the Americas. After early humans migrated to the Americas about 13,000 BP, their hunting and other associated ecological impacts led to the extinction of many megafaunal species there. Calculations suggest that this extinction decreased methane production by about 9.6 million tons per year. This suggests that the absence of megafaunal methane emissions may have contributed to the abrupt climatic cooling at the onset of the Younger Dryas.[54] The decrease in atmospheric methane that occurred at that time, as recorded in ice cores, was 2-4 times more rapid than any other decrease in the last half million years, suggesting that an unusual mechanism was at work.[54]

Examples

The following are some notable examples of animals often considered as megafauna (in the sense of the "large animal" definition). This list is not intended to be exhaustive:

- Clade Synapsida

- Class Mammalia (phylogenetically, a clade within Therapsida; see below)

- Infraclass Metatheria

- Order Diprotodontia

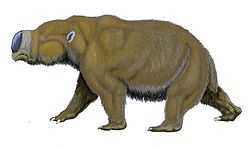

- The red kangaroo (Macropus rufus) is the largest living Australian mammal and marsupial at a weight of up to 85 kg (187 lb). However, its extinct relative, the giant short-faced kangaroo Procoptodon goliah reached 230 kg (510 lb), while extinct diprotodonts attained the largest size of any marsupial in history, up to an estimated 2,750 kg (6,060 lb). The extinct marsupial lion (Thylacleo carnifex), at up to 160 kg (350 lb) was much larger than any extant carnivorous marsupial.

- Order Diprotodontia

- Infraclass Eutheria

- Superorder Afrotheria

- Order Proboscidea

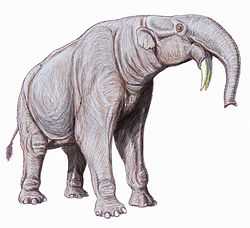

- Elephants are the largest living land animals. They and their relatives arose in Africa, but until recently had a nearly worldwide distribution. The African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana) has a shoulder height of up to 4.3 m (14 ft) and weighs up to 13 tons. Among recently extinct proboscideans, mammoths (Mammuthus) were close relatives of elephants, while mastodons (Mammut) were much more distantly related. The steppe mammoth (M. trogontherii) is estimated to have commonly weighed around 10 tonnes, making it possibly the largest proboscid, which would make it the second largest land mammal after indricotherines.

- Order Sirenia

- The largest sirenian at up to 1500 kg is the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus). Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) was probably around five times as massive, but was exterminated by humans within 27 years of its discovery off the remote Commander Islands in 1741. In prehistoric times this sea cow also lived along the coasts of northeastern Asia and northwestern North America; it was apparently eliminated from these more accessible locations by aboriginal hunters.

- Order Proboscidea

- Superorder Xenarthra

- Order Cingulata

- The glyptodonts were a group of large, heavily armored ankylosaur-like xenarthrans related to living armadillos. They originated in South America, invaded North America during the Great American Interchange, and went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch.[56]

- Order Pilosa

- Ground sloths were another group of slow, terrestrial xenarthrans, related to modern tree sloths. They had a similar history, although they reached North America earlier, and spread farther north (e.g., Megalonyx). The largest genera, Megatherium and Eremotherium, reached sizes comparable to elephants.[56]

- Order Cingulata

- Superorder Euarchontoglires

- Order Primates

- The largest living primate, at up to 266 kg (586 lb), is the gorilla (Gorilla beringei and Gorilla gorilla, with three of four subspecies being critically endangered). The extinct Malagasy sloth lemur Archaeoindris reached a similar size, while the extinct Gigantopithecus blacki of Southeast Asia is believed to have been several times larger. Some populations of archaic Homo were significantly larger than recent Homo sapiens;[57][58] for example, Homo heidelbergensis in southern Africa may have commonly reached 7 feet (2.1 m) in height,[59] while Neanderthals were about 30% more massive.[60]

- Order Rodentia

- The extant capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) of South America, the largest living rodent, weighs up to 65 kg (143 lb). Several recently extinct North American forms were larger: the capybara Neochoerus pinckneyi (another neotropic migrant) was about 40% heavier; the giant beaver (Castoroides ohioensis) was similar. The extinct blunt-toothed giant hutia (Amblyrhiza inundata) of several Caribbean islands may have been larger still. However, several million years ago South America harbored much more massive rodents. Phoberomys pattersoni, known from a nearly full skeleton, probably reached 700 kg (1,500 lb). Fragmentary remains suggest that Josephoartigasia monesi grew to upwards of 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).

- Order Primates

- Superorder Laurasiatheria

- Order Carnivora

- Big cats include the tiger (Panthera tigris) and lion (Panthera leo). The largest subspecies, at up to 306 kg (675 lb), is the Siberian tiger (P. tigris altaica), in accord with Bergmann's rule. Members of Panthera are distinguished by morphological features which enable them to roar. Larger extinct felids include the American lion (Panthera leo atrox) and the South American saber-toothed cat Smilodon populator.

- Bears are large carnivorans of the caniform suborder. The largest living forms are the polar bear (Ursus maritimus), with a body weight of up to 680 kg (1,500 lb), and the similarly sized Kodiak bear (Ursus arctos middendorffi), again consistent with Bergmann's rule. Arctotherium augustans, an extinct short-faced bear from South America, was the largest predatory land mammal ever with an estimated average weight of 1,600 kg (3,500 lb).[61]

- Seals, sea lions, and walruses are amphibious marine carnivorans that evolved from bearlike ancestors. The southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina) of Antarctic and subantarctic waters is the largest carnivoran of all time, with bull males reaching a maximum length of 6–7 m (20–23 ft) and maximum weight of 5,000 kg (11,000 lb).

- Order Perissodactyla

- Tapirs are browsing animals, with a short prehensile snout and pig-like form that appears to have changed little in 20 million years. They inhabit tropical forests of Southeast Asia and South and Central America, and include the largest surviving land animals of the latter two regions. There are four species.

- Rhinoceroses are odd-toed ungulates with horns made of keratin, the same type of protein composing hair. They are among the largest living land mammals after elephants (hippos attain a similar size). Three of five extant species are critically endangered. Their extinct central Asian relatives the indricotherines were the largest terrestrial mammals of all time.

Rhinoceros, from Dürer's woodcut

Rhinoceros, from Dürer's woodcut

- Order Artiodactyla (or cladistically, Cetartiodactyla)

- Giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) are the tallest living land animals, reaching heights of up to nearly 6 m (20 ft).

- Bovine ungulates include the largest surviving land animals of Europe and North America. The water buffalo (Bubalis arnee), bison (Bison bison and B. bonasus), and gaur (Bos gaurus) can all grow to weights of over 900 kg (2,000 lb).

- The semiaquatic hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) is the heaviest living even-toed ungulate; it and the critically endangered pygmy hippo (Choeropsis liberiensis) are believed to be the closest extant relatives of cetaceans. Hippos are among the megafaunal species most dangerous to humans.[62]

- Order Cetacea (or cladistically, Cetartiodactyla)

- Whales, dolphins, and porpoises are marine mammals. The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest baleen whale and the largest animal that has ever lived, at 30 metres (98 ft)[63] in length and 170 tonnes (190 short tons)[64] or more in weight. The sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is the largest toothed whale, as well as the planet's loudest and brainiest animal (with a brain about five times as massive as a human's). The killer whale (Orcinus orca) is the largest dolphin.

- Order Carnivora

- Superorder Afrotheria

- Infraclass Metatheria

- Order Pelycosauria (traditional; paraphyletic)

- Cotylorhynchus was a large, big-clawed, herbivorous caseid of Early Permian North America, reaching 6 m (20 ft) and 2 tonnes.

- Order Therapsida

- Anteosaurus was a headbutting, semiaquatic, carnivorous dinocephalian of Middle Permian South Africa. It reached 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long, and weighed about 500–600 kg (1,100–1,300 lb).[65]

- Class Mammalia (phylogenetically, a clade within Therapsida; see below)

- Clade Sauropsida

- Class Aves (phylogenetically, a clade within Coelurosauria, a taxon within the order Saurischia; see below)

- Order Struthioniformes

- The ratites are an ancient and diverse group of flightless birds that are found on fragments of the former supercontinent Gondwana. The largest living bird, the ostrich (Struthio camelus) was surpassed by the extinct Aepyornis of Madagascar, the heaviest of the group (400 kg (880 lb)), and the extinct giant moa (Dinornis) of New Zealand, the tallest, growing to heights of 3.4 m (11 ft). The latter two are examples of island gigantism.

- Order Anseriformes

- Extinct dromornithids of Australia such as Dromornis may have exceeded the largest ratites in size. (Due to its small size for a continent and its isolation, Australia is sometimes viewed as the world's largest island; thus, these species could also be considered insular giants.)

- Order Struthioniformes

- Class Reptilia (traditional; paraphyletic)

- Order Crocodilia

- Alligators and crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles, the largest of which, the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), can grow to a weight of 1,360 kg (3,000 lb). Crocodilians' distant ancestors and their kin, the pseudosuchians (traditional crurotarsans), dominated the world in the late Triassic, until the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event allowed dinosaurs to overtake them. They remained diverse during the later Mesozoic, when crocodyliforms such as Deinosuchus and Sarcosuchus reached lengths of 12 m. Similarly large crocodilians, such as Mourasuchus and Purussaurus, were present as recently as the Miocene in South America.

- Order Saurischia

- Saurischian dinosaurs of the Jurassic and Cretaceous include sauropods, the longest (at up to 40 m or 130 ft) and most massive terrestrial animals known (Argentinosaurus reached 80–100 metric tonnes, or 90–110 tons), as well as theropods, the largest terrestrial carnivores (Spinosaurus grew to 7–9 tonnes; the more famous Tyrannosaurus, to 6.8 tonnes).

- Order Squamata

- While the largest extant lizard, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), another island giant, can reach 3 m (10 ft) in length, its extinct Australian relative Megalania may have reached more than twice that size. These monitor lizards' marine relatives, the mosasaurs, were apex predators in late Cretaceous seas.

- The heaviest extant snake is considered to be the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus), while the reticulated python (Python reticulatus), at up to 8.7 m or more, is considered the longest. An extinct Australian Pliocene species of Liasis, the Bluff Downs giant python, reached 10 m, while the Paleocene Titanoboa of South America reached lengths of 12–15 m and an estimated weight of about 1135 kilograms (2500 lb).

- Order Testudines

- The largest turtle is the critically endangered marine leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), weighing up to 900 kg (2,000 lb). It is distinguished from other sea turtles by its lack of a bony shell. The most massive terrestrial chelonians are the giant tortoises of the Galápagos Islands (Chelonoidis nigra) and Aldabra Atoll (Aldabrachelys gigantea), at up to 300 kg (660 lb). These tortoises are the biggest survivors of an assortment of giant tortoise species that were widely present on continental landmasses[66][67] and additional islands[66] during the Pleistocene.

- Order Crocodilia

- Class Aves (phylogenetically, a clade within Coelurosauria, a taxon within the order Saurischia; see below)

- Class Amphibia (in the wide, probably paraphyletic, sense)

- Order Temnospondyli (relationship to extant amphibians is unclear)

- The Permian temnospondyl Prionosuchus, the largest amphibian known, reached 9 m in length and was an aquatic predator resembling a crocodilian. After the appearance of real crocodilians, temnospondyls such as Koolasuchus (5 m long) had retreated to the Antarctic region by the Cretaceous, before going extinct.

- Order Temnospondyli (relationship to extant amphibians is unclear)

- Class Actinopterygii

- Order Tetraodontiformes

- The largest extant bony fish is the ocean sunfish (Mola mola), whose average adult weight is 1,000 kg (2,200 lb). While phylogenetically a "bony fish", its skeleton is primarily cartilage (which is lighter than bone). It has a disk-shaped body, and propels itself with its long, thin dorsal and anal fins; it feeds primarily on jellyfish. In these three respects (as well as in its size and diving habits), it resembles a leatherback turtle.

- Order Acipenseriformes

- Order Siluriformes

- The critically endangered Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas), at up to 293 kg (646 lb), is often viewed as the largest freshwater fish.

- Order Tetraodontiformes

- Class Chondrichthyes

- Order Lamniformes

- The largest living predatory fish, the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), reaches weights up to 2,240 kg (4,940 lb). Its extinct relative C. megalodon (the disputed genus being either Carcharodon or Carcharocles) was more than an order of magnitude larger, and is the largest predatory shark or fish of all time (and possibly the largest predator in vertebrate history); it preyed on whales and other marine mammals.

- Order Orectolobiformes

- The largest extant shark, cartilaginous fish, and fish overall is the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), which reaches weights in excess of 21.5 tonnes (47,000 pounds). Like baleen whales, it is a filter feeder and primarily consumes plankton.

- Order Rajiformes

- Order Lamniformes

- Class Placodermi

- Order Arthrodira

- The largest armored fish, Dunkleosteus, arose during the late Devonian. At up to 10 metres (33 ft) in length[68] and 3.6 tonnes (4.0 short tons) in mass,[69] it was a hypercarnivorous apex predator that employed suction feeding.[70][71] Its contemporary, Titanichthys, apparently an early filter feeder, rivaled it in size. The anthrodires were eliminated by the environmental upheavals of the Late Devonian extinction, after existing for only about 50 million years.

- Order Arthrodira

- Class Cephalopoda

- Order Teuthida

- A number of deep ocean creatures exhibit abyssal gigantism. These include the giant squid (Architeuthis) and colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni); both (although rarely seen) are believed to attain lengths of 12 m (39 ft) or more. The latter is the world's largest invertebrate, and has the largest eyes of any animal. Both are preyed upon by sperm whales.

- Order Teuthida

- Stem-group Arthropoda

- Order Radiodonta

- Anomalocarids were a group of very early legless marine arthropods that included the largest predators of the Cambrian, such as Anomalocaris. By the early Ordovician they had evolved into giant (for the time) filter feeders, apparently in response to the proliferation of plankton during the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event. Aegirocassis grew to over 2 m in length.[72]

- Order Eurypterida

- Eurypterids (sea scorpions) were a diverse group of aquatic and possibly amphibious predators that included the most massive arthropods to have existed. They survived over 200 million years, but finally died out in the Permian–Triassic extinction event along with trilobites and most other forms of life present at the time, including most of the dominant terrestrial therapsids. The Early Devonian Jaekelopterus reached an estimated length of 2.5 m (8.2 ft), not including its raptorial chelicerae, and is thought to have been a freshwater species.

- Order Radiodonta

Gallery

Extinct

-

Some Paleozoic sea scorpions (Eurypterus shown) were larger than a man.

-

Dunkleosteus was a 10 m (33 ft) long toothless armored predatory Devonian placoderm fish.

-

Sail-backed pelycosaur Dimetrodon and temnospondyl Eryops from North America's Permian.

-

Pliosaur Pliosaurus (right) harassing the filter feeder fish Leedsichthys during the Jurassic.

-

Macronarian sauropods; from left, Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Giraffatitan, Euhelopus.

-

Tyrannosaurus was a 12.3 m (40 ft) long theropod dinosaur, an apex predator of west North America.

-

Indricotheres, the land mammals closest to sauropods in size and lifestyle, were Asian rhinos.

-

The Late Miocene teratorn Argentavis of South America had a 7 m (23 ft) wingspan.

-

C. megalodon (two possible sizes) with a whale shark, great white shark and human for scale.

-

Deinotherium had downward-curving tusks and ranged widely over Afro-Eurasia.

-

Titanis walleri, the only terror bird known to have invaded North America, was 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) tall.

-

Hippo-sized Diprotodon of Australia, the largest marsupial of all time, went extinct 40,000 years ago.

-

.jpg)

Glyptodon, from South America's Pleistocene, was an auto-sized cingulate, a relative of armadillos.

-

Macrauchenia, South America's last and largest litoptern, likely had a short trunk like a saiga.

-

American lions exceeded extant lions in size and ranged over two continents until 10,000 BP.

-

_-_Mauricio_Ant%C3%B3n.jpg)

Woolly mammoths vanished after humans invaded their habitat in Eurasia and N. America.[1]

-

Haast's eagle, the largest eagle known, attacking moa (which included the tallest bird known).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Stuartwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Living

-

The eastern gorilla is the largest and one of the more endangered primates on the planet.

-

The most common tiger subspecies, Bengal tigers are endangered by poaching and habitat destruction.

-

Polar bears, among the largest bears (consistent with Bergmann's rule), are vulnerable to global warming.

-

The critically endangered black rhinoceros, up to 14 feet (4.3 m) long, is threatened by poaching.

-

Wild Bactrian camels are critically endangered. Their ancestors originated in North America.

-

Unlike woolly rhinos and mammoths, muskoxen narrowly survived the Quaternary extinctions.[1]

-

Hippos, the heaviest and most aquatic even-toed ungulates, are whales' closest living relatives.

-

The sperm whale, the largest toothed whale and toothed predator, has the biggest brain.

-

The orca, the largest dolphin and pack predator, is highly intelligent and lives in complex societies.

-

The cassowary, the heaviest non-African bird, can run at 50 km/h through dense rainforest.

-

.jpg)

The saltwater crocodile is the largest living reptile and a dangerous predator of humans.

-

The Komodo dragon, an insular giant and the largest lizard, has serrated teeth and a venomous bite.

-

The green anaconda, an aquatic constrictor, is the heaviest snake, weighing up to 97.5 kg (215 lb).

-

The deep-diving ocean sunfish is the largest bony fish, but its skeleton is mostly cartilaginous.

-

The Nile perch, one of the largest freshwater fish, is also a damaging invasive species.[note 1]

-

The great white, the largest macropredatory fish, is responsible for the most shark attacks.

-

Examination of a 9 m giant squid, an abyssal giant and the second largest cephalopod.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Stuartwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

See also

- Australian megafauna

- Bergmann's rule

- Charismatic megafauna

- Cope's rule

- Deep-sea gigantism

- Fauna

- Giant animals in fiction and mythology

- Island dwarfism

- Island gigantism

- Largest organisms

- Largest prehistoric organisms

- List of megafauna discovered in modern times

- Megafauna (categories)

- Africa

- Australia

- Eurasia

- North America

- South America

- New World Pleistocene extinctions

- Pleistocene megafauna

- Quaternary extinction event

Notes

References

- ↑ Stuart, A. J. (November 1991). "Mammalian extinctions in the Late Pleistocene of northern Eurasia and North America". Biological Reviews (Wiley) 66 (4): 453–562. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1991.tb01149.x.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Johnson, C. N. (2002-09-23). "Determinants of Loss of Mammal Species during the Late Quaternary 'Megafauna' Extinctions: Life History and Ecology, but Not Body Size". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B (The Royal Society) 269 (1506): 2221–2227 (see p. 2225). doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2130. JSTOR 3558643.

- ↑ Martin, P. S.; Steadman, D. W. (1999-06-30). "Prehistoric extinctions on islands and continents". In MacPhee, R. D. E. Extinctions in near time: causes, contexts and consequences. Advances in Vertebrate Paleontology 2. New York: Kluwer/Plenum. pp. 17–56. ISBN 978-0-306-46092-0. OCLC 41368299. Retrieved 2011-08-23.

- ↑ Ice Age Animals. Illinois State Museum

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Evans, A. R. et al. (2012-01-30). "The maximum rate of mammal evolution". PNAS 109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120774109. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Smith, F. A.; Boyer, A. G.; Brown, J. H.; Costa, D. P.; Dayan, T.; Ernest, S. K. M.; Evans, A. R.; Fortelius, M.; Gittleman, J. L.; Hamilton, M. J.; Harding, L. E.; Lintulaakso, K.; Lyons, S. K.; McCain, C.; Okie, J. G.; Saarinen, J. J.; Sibly, R. M.; Stephens, P. R.; Theodor, J.; Uhen, M. D. (2010-11-26). "The Evolution of Maximum Body Size of Terrestrial Mammals". Science 330 (6008): 1216–1219. Bibcode:2010Sci...330.1216S. doi:10.1126/science.1194830. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ↑ Clauss, M.; Frey, R.; Kiefer, B.; Lechner-Doll, M.; Loehlein, W.; Polster, C.; Roessner, G. E.; Streich, W. J. (2003-04-24). "The maximum attainable body size of herbivorous mammals: morphophysiological constraints on foregut, and adaptations of hindgut fermenters". Oecologia 136 (1): 14–27. doi:10.1007/s00442-003-1254-z. PMID 12712314. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sorkin, B. (2008-04-10). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators". Lethaia 41 (4): 333–347. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00091.x. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- ↑ Carbone, C.; Teacher, A; Rowcliffe, J. M. (2007-01-16). "The Costs of Carnivory". PLoS Biology 5 (2, e22): 363–368. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050022. PMC 1769424. PMID 17227145. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Ashton, K. G.; Tracy, M. C.; de Queiroz, A. (October 2000). "Is Bergmann’s Rule Valid for Mammals?". The American Naturalist 156 (4): 390–415. doi:10.1086/303400. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ↑ Webb, J. (2015-02-19). "Evolution 'favours bigger sea creatures'". BBC. Retrieved 2015-02-22.

- ↑ Heim, N. A.; Knope, M. L.; Schaal, E. K.; Wang, S. C.; Payne, J. L. (2015-02-20). "Cope’s rule in the evolution of marine animals". Science 347 (6224): 867–870. doi:10.1126/science.1260065. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- ↑ Thewissen, J. G. M.; Bajpai, S. (1 January 2001). "Whale Origins as a Poster Child for Macroevolution". BioScience 51 (12): 1037–1049. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[1037:WOAAPC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Mitchell, K. J.; Llamas, B.; Soubrier, J.; Rawlence, N. J.; Worthy, T. H.; Wood, J.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Cooper, A. (2014-05-23). "Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution". Science 344 (6186): 898–900. doi:10.1126/science.1251981. PMID 24855267.

- ↑ Phillips MJ, Gibb GC, Crimp EA, Penny D (January 2010). "Tinamous and moa flock together: mitochondrial genome sequence analysis reveals independent losses of flight among ratites". Systematic Biology 59 (1): 90–107. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syp079. PMID 20525622.

- ↑ Baker, A. J.; Haddrath, O.; McPherson, J. D.; Cloutier, A. (2014). "Genomic Support for a Moa-Tinamou Clade and Adaptive Morphological Convergence in Flightless Ratites". Molecular Biology and Evolution. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu153.

- ↑ Murray, Peter F.; Vickers-Rich, Patricia (2004). Magnificent Mihirungs: The Colossal Flightless Birds of the Australian Dreamtime. Indiana University Press. pp. 51, 314. ISBN 978-0-253-34282-9. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 212.

- ↑ Kenneth Carpenter (1999). Eggs, Nests, and Baby Dinosuars: A Look at Dinosaur Reproduction. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33497-8. OCLC 42009424. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ Jackson, F. D.; Varricchio, D. J.; Jackson, R. A.; Vila, B.; Chiappe, L. M. (2008). "Comparison of water vapor conductance in a titanosaur egg from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina and a Megaloolithus siruguei egg from Spain". Paleobiology 34 (2): 229–246. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2008)034[0229:COWVCI]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 277.

- ↑ Corlett, R. T. (2006). "Megafaunal extinctions in tropical Asia". Tropinet 17 (3): 1–3. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ↑ Edmeades, Baz. "Megafauna — First Victims of the Human-Caused Extinction". (internet-published book with Foreword by Paul S. Martin). Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Martin, P. S. (2005). "Chapter 6. Deadly Syncopation". Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Rewilding of America. University of California Press. pp. 118–128. ISBN 0-520-23141-4. OCLC 58055404. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Burney, D. A.; Flannery, T. F. (July 2005). "Fifty millennia of catastrophic extinctions after human contact". Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Elsevier) 20 (7): 395–401. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.022. PMID 16701402. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- ↑ Roberts, R. G.; Flannery, T. F.; Ayliffe, L. K.; Yoshida, H.; Olley, J. M.; Prideaux, G. J.; Laslett, G. M.; Baynes, A.; Smith, M. A.; Jones, R.; Smith, B. L. (2001-06-08). "New Ages for the Last Australian Megafauna: Continent-Wide Extinction About 46,000 Years Ago". Science 292 (5523): 1888–1892. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1888R. doi:10.1126/science.1060264. PMID 11397939. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (2008-08-13). "Palaeontology: The last giant kangaroo". Nature 454 (7206): 835–836. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..835D. doi:10.1038/454835a. PMID 18704074. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ↑ Turney, C. S. M.; Flannery, T. F.; Roberts, R. G.; et al. (2008-08-21). "Late-surviving megafauna in Tasmania, Australia, implicate human involvement in their extinction". PNAS (NAS) 105 (34): 12150–12153. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10512150T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801360105. PMC 2527880. PMID 18719103. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ↑ Roberts, R.; Jacobs, Z. (October 2008). "The Lost Giants of Tasmania". Australasian Science 29 (9): 14–17. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- ↑ Norton, C. J.; Kondo, Y.; Ono, A.; Zhang, Y.; Diab, M. C. (2009-05-23). "The nature of megafaunal extinctions during the MIS 3–2 transition in Japan". Quaternary International 211 (1–2): 113–122. Bibcode:2010QuInt.211..113N. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.05.002. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ Haynes, Gary (2009). "Introduction to the Volume". In Haynes, Gary. American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene. Springer. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8793-6_1. ISBN 978-1-4020-8792-9.

- ↑ Fiedel, Stuart (2009). "Sudden Deaths: The Chronology of Terminal Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinction". In Haynes, Gary. American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene. Springer. pp. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8793-6_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-8792-9.

- ↑ Simmons, A. H. (1999). Faunal extinction in an island society: pygmy hippopotamus hunters of Cyprus. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. p. 382. doi:10.1007/b109876. ISBN 978-0-306-46088-3. OCLC 41712246.

- ↑ Simmons, A. H.; Mandel, R. D. (December 2007). "Not Such a New Light: A Response to Ammerman and Noller". World Archaeology 39 (4): 475–482. doi:10.1080/00438240701676169. JSTOR 40026143.

- ↑ Steadman, D. W.; Martin, P. S.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Jull, A. J. T.; McDonald, H. G.; Woods, C. A.; Iturralde-Vinent, M.; Hodgins, G. W. L. (2005-08-16). "Asynchronous extinction of late Quaternary sloths on continents and islands". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (National Academy of Sciences) 102 (33): 11763–11768. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10211763S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502777102. PMC 1187974. PMID 16085711.

- ↑ Anderson, A.; Sand, C.; Petchey, F.; Worthy, T. H. (2010). "Faunal extinction and human habitation in New Caledonia: Initial results and implications of new research at the Pindai Caves". Journal of Pacific Archaeology 1 (1): 89–109. hdl:10289/5404.

- ↑ White, A. W.; Worthy, T. H.; Hawkins, S.; Bedford, S.; Spriggs, M. (2010-08-16). "Megafaunal meiolaniid horned turtles survived until early human settlement in Vanuatu, Southwest Pacific". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107 (35): 15512–15516. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10715512W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005780107. PMC 2932593. PMID 20713711.

- ↑ Burney, D. A.; Burney, L. P.; Godfrey, L. R.; Jungers, W. L.; Goodman, S. M.; Wright, H. T.; Jull. A. J. T. (July 2004). "A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution 47 (1–2): 25–63. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. PMID 15288523. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ Holdaway, R. N.; Jacomb, C. (2000-03-24). "Rapid Extinction of the Moas (Aves: Dinornithiformes): Model, Test, and Implications". Science 287 (5461): 2250–2254. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.2250H. doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2250. PMID 10731144. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ Janoo, A. (April 2005). "Discovery of isolated dodo bones (Raphus cucullatus (L.), Aves, Columbiformes) from Mauritius cave shelters highlights human predation, with a comment on the status of the family Raphidae Wetmore, 1930". Annales de Paléontologie 91 (2): 167–180. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2004.12.002. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ Anderson, P. K. (July 1995). "Competition, Predation, and the Evolution and Extinction of Steller's Sea Cow, Hydrodamalis gigas". Marine Mammal Science (Society for Marine Mammalogy) 11 (3): 391–394. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1995.tb00294.x. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- ↑ Biello, D. (2012-03-22). "Big Kill, Not Big Chill, Finished Off Giant Kangaroos". Scientific American news. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ McGlone, M. (2012-03-23). "The Hunters Did It". Science 335 (6075): 1452–1453. Bibcode:2012Sci...335.1452M. doi:10.1126/science.1220176. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Rule, S.; Brook, B. W.; Haberle, S. G.; Turney, C. S. M.; Kershaw, A. P. (2012-03-23). "The Aftermath of Megafaunal Extinction: Ecosystem Transformation in Pleistocene Australia". Science 335 (6075): 1483–1486. Bibcode:2012Sci...335.1483R. doi:10.1126/science.1214261. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ Miller, G. H.; Magee, J. W.; Johnson, B. J.; Fogel, M. L.; Spooner, N. A.; McCulloch, M. T.; Ayliffe, L. K. (1999-01-08). "Pleistocene Extinction of Genyornis newtoni: Human Impact on Australian Megafauna". Science 283 (5399): 205–208. doi:10.1126/science.283.5399.205. PMID 9880249.

- ↑ Johnson, C. (2009-11-20). "Megafaunal Decline and Fall". Science 326 (5956): 1072–1073. doi:10.1126/science.1182770. PMID 19965418.

- ↑ Gill, J. L.; Williams, J. W.; Jackson, S. T.; Lininger, K. B.; Robinson, G. S. (2009-11-20). "Pleistocene Megafaunal Collapse, Novel Plant Communities, and Enhanced Fire Regimes in North America". Science 326 (5956): 1100–1103. doi:10.1126/science.1179504. PMID 19965426.

- ↑ Alroy, J. (2008-08-12). "Dynamics of origination and extinction in the marine fossil record". PNAS. 105 Suppl 1 (Supplement_1): 11536–11542. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511536A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802597105. PMC 2556405. PMID 18695240.

- ↑ Wolf, A.; Doughty, C. E.; Malhi, Y. (2013-08-09). "Lateral Diffusion of Nutrients by Mammalian Herbivores in Terrestrial Ecosystems". PLoS ONE 8 (8): e71352. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071352.

- ↑ Marshall, M. (2013-08-11). "Ecosystems still feel the pain of ancient extinctions". New Scientist. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Doughty, C. E.; Wolf, A.; Malhi, Y. (2013-08-11). "The legacy of the Pleistocene megafauna extinctions on nutrient availability in Amazonia". Nature Geoscience. doi:10.1038/ngeo1895.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Wilkinson, D. M.; Nisbet, E. G.; Ruxton, G. D. (2012-05-08). "Could methane produced by sauropod dinosaurs have helped drive Mesozoic climate warmth?". Current Biology 22 (9): R292–R293. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.042. Retrieved 2012-05-08.

- ↑ "Dinosaur gases 'warmed the Earth'". BBC Nature News. 2012-05-07. Retrieved 2012-05-08.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Smith, F. A.; Elliot, S. M.; Lyons, S. K. (2010-05-23). "Methane emissions from extinct megafauna". Nature Geoscience (Nature Publishing Group) 3 (6): 374–375. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..374S. doi:10.1038/ngeo877. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ↑ Kelliher, F. M.; Clark, H. (2010-03-15). "Methane emissions from bison—An historic herd estimate for the North American Great Plains". Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 150 (3): 473–577. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2009.11.019.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Fariña, Richard A.; Vizcaíno, Sergio F.; De Iuliis, Gerry (22 May 2013). Megafauna: Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-00719-4. OCLC 779244424.

- ↑ Ruff, C. B.; Trinkaus, E.; Holliday, T. W. (1997-05-08). "Body mass and encephalization in Pleistocene Homo". Nature 387 (6629): 173–176. Bibcode:1997Natur.387..173R. doi:10.1038/387173a0. PMID 9144286. Retrieved 2012-05-25.

- ↑ Grine, F. E.; Jumgers, W. L.; Tobias, P. V.; Pearson, O. M. (June 1995). "Fossil Homo femur from Berg Aukas, northern Namibia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 97 (2): 151–185. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330970207. PMID 7653506.

- ↑ Smith, Chris; Burger, Lee (November 2007). "Our Story: Human Ancestor Fossils". The Naked Scientists. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ↑ Kappelman, John (1997-05-08). "They might be giants". Nature 387 (6629): 126–127. Bibcode:1997Natur.387..126K. doi:10.1038/387126a0. PMID 9144276. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ↑ Soibelzon, L. H.; Schubert, B. W. (January 2011). "The Largest Known Bear, Arctotherium angustidens, from the Early Pleistocene Pampean Region of Argentina: With a Discussion of Size and Diet Trends in Bears". Journal of Paleontology (Paleontological Society) 85 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1666/10-037.1. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ Swift, E. M. (1997-11-17). "What Big Mouths They Have: Travelers in Africa who run afoul of hippos may not live to tell the tale". Sports Illustrated Vault. Time Inc. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ↑ ^ J. Calambokidis and G. Steiger (1998). Blue Whales. Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-89658-338-4.

- ↑ ^ "Animal Records". Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ↑ Anteosaurus. Palaeos.org (2013-04-22)

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Hansen, D. M.; Donlan, C. J.; Griffiths, C. J.; Campbell, K. J. (April 2010). "Ecological history and latent conservation potential: large and giant tortoises as a model for taxon substitutions". Ecography (Wiley) 33 (2): 272–284. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06305.x. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ↑ Cione, A. L.; Tonni, E. P.; Soibelzon, L. (2003). "The Broken Zig-Zag: Late Cenozoic large mammal and tortoise extinction in South America". Rev. Mus. Argentino Cienc. Nat., n.s. 5 (1): 1–19. ISSN 1514-5158. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

- ↑ Palmer, D. (1 July 2002). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. New Line Books. ISBN 978-1-57717-293-2. OCLC 183092423. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ↑ Monster fish crushed opposition with strongest bite ever. The Sydney Morning Herald. November 30, 2006.

- ↑ Anderson, P. S.L; Westneat, M. W (2006-11-28). "Feeding mechanics and bite force modelling of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, an ancient apex predator". Biology Letters 3 (1): 77–80. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0569. ISSN 1744-9561.

- ↑ Anderson, P.S.L. (2010-05-04). "Using linkage models to explore skull kinematic diversity and functional convergence in arthrodire placoderms". Journal of Morphology: 990–1005. doi:10.1002/jmor.10850. ISSN 0362-2525.

- ↑ Van Roy, P.; Daley, A. C.; Briggs, D. E. G. (11 March 2015). "Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps". Nature (Nature Publishing Group). doi:10.1038/nature14256.