Media richness theory

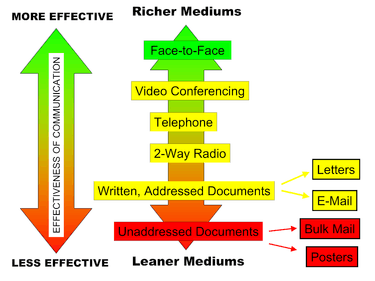

Media richness theory, sometimes referred to as information richness theory, is a framework to describe a communications medium by its ability to reproduce the information sent over it. It was developed by Richard L. Daft and Robert H. Lengel, and is used to rank and evaluate the richness of certain communication mediums, such as phone calls, video conferencing, and email. For example, a phone call can not reproduce visual social cues such as gestures, so it is a less rich communication medium than video conferencing, which allows users to communicate gestures to some extent. Specifically, media richness theory states that the more ambiguous and uncertain a task is, the richer the format of media that suits it. Based on contingency theory and information processing theory, it explains that richer, personal communication means are generally more effective for communication of equivocal issues than leaner, less rich media.

Background

Media richness theory was introduced in 1984 by Richard L. Daft and Robert H. Lengel. It was originally developed primarily to describe and evaluate communication mediums within organizations. It is based on information processing theory and how managers and organizations exchange information.[1] The goal of Media richness theory is to cope with communication challenges facing organizations, such as unclear or confusing messages, or conflicting interpretations of messages.[2] Since it was first introduced, Media richness theory has been a widely studied communication theory, and the original authors have written several additional articles on the topic, including a study in which they describe media richness and the ability to select appropriate media as an executive skill.[3]

Other communication scholars have tested the theory in order to improve it, and more recently Media richness theory has been retroactively adapted to include new media communication mediums, such as improved video and online conferencing. Although Media richness theory relates to media use, rather than media choice, empirical studies of the theory have often studied what medium a manager would choose to communicate over, and not the effects of media use.[4]

Since its introduction, Media richness theory has been applied to contexts outside of organizational and business communication (See "Application" section).

Theory

Information richness is defined by Daft and Lengel as "the ability of information to change understanding within a time interval".[2]

Media richness theory states that all communication media vary in their ability to enable users to communicate and change understanding - their "richness".[5] Communications that can overcome different frames of reference and clarify ambiguous issues to promote understanding in a timely manner are considered more rich. Communications that take a longer time to convey understanding are less rich. One main purpose of choosing a communication medium is to reduce the equivocality of a message. Equivocality exists when there are multiple and possibly conflicting interpretations for the information or the framework with which to interpret it.[5] If a message is equivocal, it is unclear and thus more difficult for the receiver to decode. The more equivocal a message, the more cues and data needed to understand it, and media richness theory places communication mediums on a continuous scale that represents the richness of a medium and its ability to adequately communicate a complex message.[6] For example, a simple message intended to arrange a meeting time and place could be communicated in a short email, but a more detailed message about a person's work performance and expectations would be better communicated through face-to-face interaction.

The theory includes a framework with axes going from low to high equivocality, and low to high uncertainty, with low equivocality and low uncertainty being a clear, well-defined situation, and high equivocality and high uncertainty being ambiguous events that need clarification by managers. Daft and Lengel also stress that message clarity may be compromised when multiple departments are communicating with each other, as departments may be trained in different skill sets or have conflicting communication norms.

Determining media richness

In their 1988 article regarding media richness theory, Daft and Lengel state, "The more learning that can be pumped through a medium, the richer the medium."[3] Media richness is a function of characteristics including the following:[1][3]

- Ability to handle multiple information cues simultaneously

- Ability to facilitate rapid feedback

- Ability to establish a personal focus

- Ability to utilize natural language

Social presence refers to the degree to which a medium permits communicators to experience others as being psychologically present, or the degree to which a medium is perceived to convey the actual presence of the communicating participants. Tasks that involve interpersonal skills, such as resolving disagreements or negotiation, demand high social presence, whereas tasks such as exchanging routine information are low in their social presence requirements. Therefore, media like face-to-face and group meetings are more appropriate for performing tasks that require high social presence, whereas media such as email and written letters are more appropriate for tasks with low social presence requirements.[7]

Media richness theory predicts that managers will choose the mode of communication based on matching the equivocality of the message to the richness of the medium, however, often other factors come into play, such as the resources available to the communicator. This assumes that managers are most concentrated on task efficiency (that is, achieving the goal as efficiently as possible), and does not take into consideration other factors, such as relationship building.[8] It has been pointed out by subsequent researchers that attitudes towards a medium may not accurately predict a persons likelihood of using that medium over others, as media usage is not always voluntary. If an organization's norms and resources support one medium, it may be difficult for a manager to choose another to communicate his or her message.[9]

The richness of a medium also comes into play when considering how personal a message is. In general, richer mediums are more personal as they include nonverbal and verbal cues, body language, inflection, and gestures that signal a persons reaction to a message. Rich mediums can promote a closer relationship between a manager and subordinate. Whether a message is positive or negative may also have an influence on the medium chosen. Managers may want to communicate negative messages in person or via a richer media, even if the equivocality of the message is not high, to facilitate better relationships with subordinates. On the other hand, sending a negative message over a leaner medium would weaken the immediate blame on the message sender, and prevent them from seeing the reaction of the receiver.[8]

Concurrency

In April 1993, Valacich et al. suggested that in light of new media, concurrency be included as an additional characteristic to determine a medium's richness. They define "environmental concurrency to represent the communication capacity of the environment to support distinct communication episodes, without detracting from any other episodes that may be occurring simultaneously between the same or different individuals." Furthermore, they explain that while this idea of concurrency could be applied to the media described in Daft and Lengel's original theories, new media provide a greater opportunity for concurrency than ever before.[10]

Application

Media Richness Theory implies that a sender should select a medium of appropriate richness to communicate the desired message or fulfill an specific task.[3] In their 1989 article, Daft and Lengel said that richer media are better suited for equivocal, non-routine messages, while leaner media are better suited for unequivocal, routine messages.[3] Actually, senders are often forced to use less-rich methods of communication. Senders that use less-rich communication media should understand the limitations of that medium in the dimensions of feedback, multiple cues, message tailoring, and emotions. Take for example the relative difficulty of determining whether a modern text message is serious or sarcastic in tone.[11]

Organizational and business communications

Media richness theory was originally conceived in an organizational communication setting to better understand interaction within companies. For example, organizations may find that since email is a less rich medium, they need to have face-to-face interactions with co-workers to make important decisions. The theory states that the more ambiguous a message is to the receiver, the more rich a medium needed to communicate it. Different media have varying benefits and drawbacks, some are more immediate than others, and some media communicate vocal or other cues more accurately. In general, media richness is used to determine the "best" medium for an individual or organization to communicate a message.[12]

From an organizational perspective, high level personnel need verbal media to solve their problems while those at the bottom of the hierarchy perform their unambiguous organizational roles with written and quantitative information. From an individual perspective, however, people prefer oral communication because this information can be evaluated more precisely in terms of the problem discussed. The primary benefit of oral communication is access to the nonverbal behavior which many perceive as a valid source of information.[13]

An information-processing perspective of organizations highlights the important role of communication. This perspective suggests that organizations gather information from their environment, process this information, and then act on it. As environmental complexity, turbulence , and information load increase, organizational communication increases. Often functioning in complex environments with rapid and discontinuous change , the organization’ s effectiveness in processing information becomes paramount.

Nowadays companies use technologies such as video conferencing, which enable participants to see each other even when in separate locations, provide the opportunity for organizations to have a richer communication media than the traditional conference call who only provide audio queues to the participants involved in such call.

Media Sensitivity and job performance

Lengel and Daft also asserted that not all executives or managers in organizations demonstrate the same skill in making effective media choices for communications, matching message contents with media richness. High performing executives or managers tend to be more "sensitive" to richness requirements in media selection than low performing manager. In other words, they select rich media for non-routine messages and lean media for routine messages.[14]

From the consensus and satisfaction perspectives, groups with a communication medium which is too lean for their task seem to experience more difficulties than groups with a communication medium which is too rich for their task. With the preference task, face-to-face groups achieved higher consensus change and experienced higher decision satisfaction and higher decision scheme satisfaction than dispersed groups. From the consensus and satisfaction perspectives, groups with a communication medium which is too lean for their task seem to experience more difficulties than groups with a communication medium which is too rich for their task.[15]

Job Seeking and Recruitment

In a recruitment context, face-to-face interactions with company representatives such as career fair interactions should be perceived by applicants as rich media. Career fairs allow instant feedback in the form of questions and answers and permit multiple cues including verbal messages and body gestures and can be tailored to each job seeker's interests and questions.

In comparison, static messages like reading information on a company's Web site or browsing an electronic bulletin board can be defined as leaner media since they are not customized to the individual needs of job seekers; they are asynchronous in their feedback and since they are primarily text-based there are no opportunities for verbal inflections or body gestures.This interaction between job seekers and potential employers is important because it affects how they process information about the organization. Things like pursuing or accepting jobs with the organization and what to expect from the organization as new employees can be shaped by the job seeker's beliefs.[16]

Extended application in new media

While Media richness theory's application to new media has been contested (see "Criticism"), it is still used heuristically as a basis for studies examining new media.

Websites and hypertext

Websites as a new medium can vary in their richness. In a study examining representations of the former Yugoslavia on the World Wide Web, Jackson and Purcell proposed that hypertext plays a role in determining the richness of individual websites. They developed a framework of criteria in which the use of hypertext on a website can be evaluated in terms of media richness characteristics as set forth by Daft and Lengel in their original theoretical literature.[17] Furthermore, in their 2004 article, Simon and Peppas examined product websites' richness in terms of multimedia use. They classified "rich media sites" as those that included text, pictures, sounds and video clips, while the "lean media sites" contained only text. In their study, they created four sites (two rich and two lean) to describe two products (one simple, one complex). They found that most users, regardless of the complexity of the product, preferred the websites that provided richer media.[18]

Instant messaging

Results from a study conducted by Anandarajan et al. on Generation Y's use of instant messaging conclude that "the more users recognize IM as a rich communication medium, the more likely they believe this medium is useful for socialization." [19] Additionally, in order to better understand teenagers' use of MSN (later called Microsoft Messenger service), Sheer examined the impact of both media richness and communication control. Among other findings, Sheer's study demonstrated that "rich features, such as webcam and MSN Spaces seemingly facilitated the increase of acquaintances, new friends, opposite-sex friends, and, thus, the total number of friends."[20]

Distance education and e-books

In evaluating students' satisfaction with distance courses, Sheppherd and Martz concluded that a course's use of media rich technology impacted how students evaluated the quality of the course. Courses that utilized tools such as "discussion forums, document sharing areas, and web casting" were viewed more favorably.[21] Lai and Chang in 2011 used media richness as a variable in their study examining user attitudes towards e-books, stating that the potential for rich media content like embedded hyperlinks and other multimedia additions, offered users a different reading experience than a printed book.[22]

E-books and e-learning are becoming recurrent tools in the academic landscape. One of the key characteristics of e-learning is its capability to integrate different media, such as text, picture, audio, animation and video to create multimedia instructional material.[23] Media selection in e-learning can be a critical issue because of the increased costs of developing non-textual e-learning materials. Learners can benefit from the use of richer media in courses than contain equivocal and uncertain content; however, learners achieve no significant benefit in either learner score or learner satisfaction from the use of richer media in courses containing low equivocal (numeric) content.[24]

In recent years, as the general population has become more e-mail savvy, the lines have blurred somewhat between F2F and e-mail communication, and e-mail rather than being considered as an instant information transfer tool, is now thought of as a verbal tool, with its capacity to enable immediate feedback, natural language, such as ‘‘cheers’’, or ‘‘emoticons’’ which have been defined as "graphic representations of facial expressions that many e-mail users embed in their messages".

However, there is a downside of e-mail the complaint of overload. There are "large unnecessary quantities of information", much of this information is non-job essential and some of it is spam, yet time has to be spent reading it. This can cause an overload, although it should be noted that this perception differs from employee to employee. People feel that they may miss out information because of this overload, and feel the need to open e-mails they might instinctively think they are irrelevant. This has made some people harder to contact via-email because their inboxes are filled with numerous e-mails, and therefore have found it difficult to filter the important ones and provide responses.[25]

Online Shopping

The perceived richness of an online store will have to be considered when analyzing online buying content. The consumer's web experience, income and trust in the online store have a significant positive effect on the consumer's intent of making online purchases. A consumer's Web experience has a significant positive effect on the perceived richness of the online store, whereas the perceived risk related to the use of the online store has a significant negative effect on the consumer's trust in an attitude towards the online store. According to media richness theory, an online store will be more efficient for analyzable tasks and a bricks-and-mortar store for unanalyzable tasks.

This knowledge will allow companies to efficiently adapt the way they use their online store, and how they deploy their multi-channel strategies in order to better meet consumers’ needs. Therefore, online retailers need to understand the nature of the consumer’s task in the shopping process and how the consumer perceives an online store's richness.[26]

Criticism

Scope of the Theory

Media richness theory was criticized in the past by what many researchers saw as its deterministic nature. Markus argued that social pressures can influence media use much more strongly than richness, and in ways that are inconsistent with media richness theory's key tenets.[27] It has also been noted that media richness theory should not assume that the feelings towards using a richer media in a situation are completely opposite to using a leaner media. In fact, media choice is complex and in general even if a rich media is considered to be the "best" to communicate a message, this does not mean leaner media would not be able to communicate the message at all.[28] Although use of leaner or richer medium may make a difference for some tasks, for other tasks the use of media makes no difference to the accuracy with which the message is communicated.[29]

If individuals are uncomfortable or unfamiliar with using an email system to distribute a message, and view learning to send an email as more time consuming and inefficient than having a group meeting, they would choose a richer rather than a rationally efficient medium. This behavior outcome, through irrational, is certainly a reflection upon the previously established experience.[30]

Cultural and Social limitations

Ngwenyama and Lee showed that cultural and social background influence media choice by individuals in ways that are incompatible with predictions based on media richness theory; their paper received the Paper of the Year Award in the journal MIS Quarterly.[31] Ngwenyama and Lee are not alone in their critiques regarding the limitations of media richness theory, particularly in regards to cultural and individual characteristics. In 2009, Gerritsen's study concluded that in business contexts, culture does play a role in determining the receiver's preference of medium, perhaps in terms of the culture in question's uncertainty avoidance.[32] Additionally, Dennis, Kinney, and Hung found that in terms of the actual performance of equivocal tasks, the richness of a medium has the most notable effect on teams composed entirely of females, while "matching richness to task equivocality did not improve decision quality, time, consensus, or communication satisfaction for all-male or mixed-gender teams."[33] Individually speaking, Barkhi demonstrated that communication mode and cognitive style can play a role in media preference and selection, suggesting that even in situations with identical messages and intentions, the "best" media selection can vary from person to person.[34]

Application to New media

Additionally, because media richness theory was developed before widespread use of the internet, which also introduced media like email, chat rooms, instant messaging, and more, some have questioned its ability to accurately predict what new media users may choose. Several studies have been conducted that examine media choice when given options considered to be "new media", such as voice mail and email. El-Shinnaway and Markus hypothesized that, based on media richness theory, individuals would choose to communicate messages over the more rich medium of voice mail than via email, but found that even when sending more equivocal messages, the leaner medium of email was used.[35] Also, it has been indicated that given the expanded capabilities of new media, media richness theory's unidimensional approach to categorizing different communication media in no longer sufficient to capture all the dimensions in which media types can vary.[36]

Related theories

Media Naturalness Theory

Several new theories have been developed based on Daft and Lengel's original framework. Kock argued that some of the hypotheses of media richness theory lack a scientific basis, and proposed an alternative theory - media naturalness theory - building on human evolution findings. Media naturalness theory hypothesizes that because face-to-face communication is the most "natural" method of communication, we should want our other communication methods to resemble face-to-face communication as closely as possible.[37] While media richness theory places mediums on a scale that range from low to high in richness and places face-to-face communication at the top of the scale, media naturalness theory thinks of face-to-face communication as the middle in a scale, and states that the further away one gets from face-to-face (either more or less rich), the more cognitive processing is required to comprehend a message.[38]

Media Synchronicity Theory

To help explain media richness and its application to new media, Media Synchronicity Theory was proposed. Synchronicity describes the ability of a medium to create the sense that all participants are concurrently engaged in the communication event. Media with high degrees of synchronicity, such as face-to-face meetings, offer participants the opportunity to communicate in real time, immediately observe the reactions and responses of others, and easily determine whether co-participants are fully engaged in the conversation.[39]

Media Synchronicity Theory also states that each medium has a set of abilities and that every communication interaction is composed of two processes: conveyance and convergence. These abilities include: transmission velocity, parallelism, symbol sets, rehearsability, and reaccessability.[29] Media richness is also related to adaptive structuration theory and social information processing theory, which explain the context around a communication that might have an impact on media choice.[38]

Channel Expansion Theory

Channel expansion theory was proposed by Carlson and Zmud (1999) to explain the inconsistencies found in several empirical studies. In these studies, the results showed that managers would employ "leaner" media for tasks of high equivocality. Channel expansion theory suggested that individual's media choice has a lot to do with individual's experience with the medium itself, with the communicator and also with the topic. Thus it is possible that an individual’s experience with using a certain lean medium, will prompt that individual to use it for equivocal tasks[40]

However, the theory does not suggest that knowledge-building experiences will necessarily equalize differences in richness, whether objective or perceptually-based, across different media. Put in another way, knowledge-building experiences may be positively related to perceptions of the richness of email, but this does not necessarily mean that email will be viewed as richer than another medium, such as face-to-face interaction[41]

See also

- Communication theory

- Social presence theory

- Social information processing theory

- Hyperpersonal Model

- Social Identity model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE)

- Theories of technology

- Multicommunicating

- Emotions in virtual communication

- Telecommuting

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Daft, R.L.; Lengel, R.H. (1984). Cummings, L.L.; Staw, B.M., eds. "Information richness: a new approach to managerial behavior and organizational design". Research in organizational behavior (Homewood, IL: JAI Press) 6: 191–233.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Daft, R.L. & Lengel, R.H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science 32(5), 554-571.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Lengel, Robert; Richard L. Daft (August 1989). "The Selection of Communication Media as an Executive Skill". The Academy of Management Executive (1987-1989): 225–232.

- ↑ Dennis, A.R.; Kinney, S.T. (September 1998). "Testing Media Richness Theory in New Media: The Effects of Cues, Feedback, and Task Equivocality". Information Systems Research 9 (3): 256–274. doi:10.1287/isre.9.3.256.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dennis, Alan R.; Valacich, Joseph S. (1999). "Rethinking Media Richness: Towards a Theory of Media Synchronicity". CiteSeerX: 10

.1 ..1 .108 .7118 - ↑ Carlson, John. R.; Zmud, Robert W. (April 1999). "Channel Expansion Theory and the Experiential Nature of Media Richness Perceptions". He Academy of Management Journal 42 (2): 153–170. doi:10.2307/257090.

- ↑ King, Ruth C.; Weidong, Xia (1997). "Media appropriateness: Effects of experience on communication media choice.". Decision Sciences 28.4: 877–910.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sheer, Vivian C.; Ling Chen (2004). "Improving Media Richness Theory : A Study of Interaction Goals, Message Valence, and Task Complexity in Manager-Subordinate Communication". Management Communication Quarterly 18 (76): 76. doi:10.1177/0893318904265803.

- ↑ Trevino, Linka Klebe; Jane Webster; Eric W. Stein (Mar–Apr 2000). "Making Connections: Complementary Influences on Communication Media Choices, Attitudes, and Use". Organization Science 11 (3): 163–182. doi:10.1287/orsc.11.2.163.12510.

- ↑ Valacich, Joseph; Paranka, David; George, Joey F; Nunamaker, Jr., J.F. (1993). "Communication Concurrency and the New Media: A New Dimension for Media Richness". Communication Research 20 (2): 249–276. doi:10.1177/009365093020002004.

- ↑ Newberry, Brian (2001). "Media Richness, Social Presence and Technology Supported Communication Activities in Education". Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ Rice, Ronald (June 1993). "Media Appropriateness: Using Social Presence Theory to Compare Traditional and New Organizational Media". Human Communication Research 19 (4): 451–484. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1993.tb00309.x.

- ↑ Allen, D.G.; Griffeth, R.W. (1997). "ertical and lateral information processing: The effects of gender, employee classification level, and media richness on communication and work outcomes". 50 10: 191–120.

- ↑ Lengel, Robert H.; Richard L. Daft (August 1989). "The selection of Communication media as an Executive skill". Academy of Management(1987-1989) 2 (3): 225–232. doi:10.5465/ame.1988.4277259.

- ↑ Raman, K.S.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.K. (January 1993). "An empirical study of task type and communication medium in GDSS". In System Sciences 4 (Proceeding of the Twenty-Sixth Hawaii International Conference): 161–168.

- ↑ Cable, D.M.; Yu, K.Y.T. "Managing job seekers' organizational image beliefs: The role of media richness and media credibility.". ournal of Applied Psychology 91 (4): 828.

- ↑ Jackson, Michele H.; Purcell, Darren (April 1997). "Politics and Media Richness in World Wide Web Representations of the Former Yugoslavia". Geographical Review. Cyberspace and Geographical Space 87 (2): 219–239. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.1997.tb00072.x.

- ↑ Simon, Steven John; Peppas, Spero C. (2004). "An examination of media richness theory in product Web site design: an empirical study". The Journal of Policy, Regulation and Strategy for Telecommunications, Information and Media 6 (4): 270–281. doi:10.1108/14636690410555672.

- ↑ Anandarajan, Murugan; Zaman, Maliha; Dai, Qizhi; Arinze, Bay (June 2010). "Generation Y Adoption of Instant Messaging: Examination of the Impact of Social Usefulness and Media Richness on Use Richness". IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 53 (2): 132–143. doi:10.1109/tpc.2010.2046082.

- ↑ Sheer, Vivian C. (January–March 2011). "Teenagers' Use of MSN Features, Discussion Topics, and Online Friendship Development: The Impact of Media Richness and Communication Control". Communication Quarterly 59 (1): 82–103. doi:10.1080/01463373.2010.525702.

- ↑ Shepherd, Morgan M.; Martz, Jr., WM Benjamin (Fall 2006). "Media Richness Theory and the Distance Education Environment". Journal of Computer Information Systems 47 (1): 114–122.

- ↑ Lai, Jung-Yu; Chang, Chih-Yen (2011). "User attitudes toward dedicated e-book readers for reading: The effects of convenience, compatibility and media richness". Online Information Review 35 (4): 558–580. doi:10.1108/14684521111161936.

- ↑ P.C, Sun; H.K., Cheng (2007). "The design of instructional multimedia in e-Learning: A Media Richness Theory-based approach". Computers & Education 49 (3): 662–676.

- ↑ Liu, S.H.; Liao, H.L.; Pratt, J.A. "Impact of media richness and flow on e-learning technology acceptance". Computers & Education 52 (3): 599–607.

- ↑ O'Kane, Paula; Owen, Hargie (2007). "Intentional and unintentional consequences of substituting face-to-face interaction with e-mail: An employee-based perspective.". Interacting with Computers 19 (1): 20–31.

- ↑ Brunelle, E.; Lapierre, J. (August 2008). "Testing media richness theory to explain consumers' intentions of buying online.". Proceedings of the 10th international conference on Electronic commerce: 31.

- ↑ Markus, M.L. (1994). Electronic Mail as the Medium of Managerial Choice. Organization Science, 5(4). 502-527.

- ↑ Rice, Ronald E. (November 1992). "Task Analyzability, Use of New Media, and Effectiveness: A Multi-Site Exploration of Media". Organization Science 3 (4): 475–500. doi:10.1287/orsc.3.4.475.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Dennis, Alan R.; Joseph Valacich; Cheri Speier; Michael G. Morris (1998). "Beyond Media Richness: An Empirical Test of Media Synchronicity Theory". 31st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences: 48–57.

- ↑ King, Ruth C.. Media Appropriateness: Effects of Experience on Communication Media Choice, p. 877-910

- ↑ Ngwenyama, Ojelanki K., & Lee, Allen S. (1997). Communication richness in electronic mail: Critical social theory and the contextuality of meaning. MIS Quarterly, 21(2), 145-167.

- ↑ Gerritsen, Marinel (2009). "The Impact of Culture on Media Choice: The Role of Context, Media Richness and Uncertainty Avoidance". Language for Professional Communication: Research, Practice and Training: 146–160.

- ↑ Dennis, Alan R.; Kinney, S.T.; Hung, Y.C. (August 1999). "Gender Differences in the Effects of Media Richness" (PDF). Small Group Research 30 (4): 405–437. doi:10.1177/104649649903000402.

- ↑ Barkhi, Reza (2002). "Cognitive style may mitigate the impact of communication mode". Information & Management 39 (8): 677–688. doi:10.1016/s0378-7206(01)00114-8.

- ↑ El-Shinnaway, Maha; M. Lynne Markus (1997). "The poverty of media richness theory: explaining people's choice of electronic mail vs. voice mail". International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 46 (4): 443–467. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1996.0099.

- ↑ Dennis, A. R., R. M. Fuller, et al. (2008). Media, Tasks and Communication Processes: A Theory of Media Synchronicity, MIS Quarterly, 32(3), 575-600

- ↑ Kock, N. (2005). Media richness or media naturalness? The evolution of our biological communication apparatus and its influence on our behavior toward e-communication tools. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 48(2), 117-130.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 DeRosa, Darleen M.; Donald A. Hantula, Ned Kock, & John D’Arcy (Summer–Fall 2004). "Trust and Leadership in Teamwork: A Media Naturalness Perspective". Human Resource Management 43 (2&3): 219–232. doi:10.1002/hrm.20016.

- ↑ Carlson, J.R.; George, J.F. (2004). "Media appropriateness in the conduct and discovery of deceptive communication: The relative influence of richness and synchronicity.". Group Decision and Negotiation 13 (2): 191–210.

- ↑ J. R., Carlson; Zmud, R. W (1999). "Channel expansion theory and the experimental nature of media richness perceptions". Academy of Management Journal (42): 153–170.

- ↑ Timmerman, C.E.; Madhavapeddi, S.N. (2008). "Perceptions of organizational media richness: Channel expansion effects for electronic and traditional media across richness dimensions". Professional Communication, IEEE Transactions on 51 (1): 18–32.

Further reading

- Daft, R.L. & Lengel, R.H. (1984). Information richness: a new approach to managerial behavior and organizational design. In: Cummings, L.L. & Staw, B.M. (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior 6, (191-233). Homewood, IL: JAI Press.

- Daft, R.L., Lengel, R.H., & Trevino, L.K. (1987). Message equivocality, media selection, and manager performance: Implications for information systems. MIS Quarterly, September, 355-366.

- Lengel, R.H. & Daft, R.L. (1988). The Selection of Communication Media as an Executive Skill. Academy of Management Executive, 2(3), 225-232.

- Suh, K.S. (1999). Impact of communication medium on task performance and satisfaction: an examination of media-richness theory. Information & Management, 35, 295-312.

- Trevino, L.K., Lengel, R.K. & Daft, R.L. (1987). Media Symbolism, Media Richness and media Choice in Organizations. Communication Research, 14(5), 553-574.

- Trevino, L., Lengel, R., Bodensteiner, W., Gerloff, E. & Muir, N. (1990). The richness imperative and cognitive style: The role of individual differences in media choice behavior. Management Communication Quarterly, 4(2).