Maxwell v. Dow

| Maxwell v. Dow | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Argued December 4, 1899 Decided February 26, 1900 | |||||||

| Full case name | CHARLES L. MAXWELL, Plff. in Err., v. GEORGE N. DOW | ||||||

| Citations | |||||||

| Court membership | |||||||

| |||||||

| Case opinions | |||||||

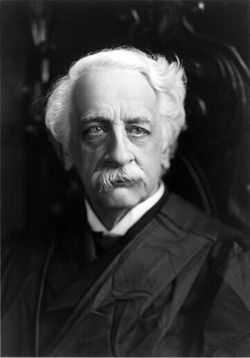

| Majority | Peckham, joined by Fuller, JJ; Gray, Brewer, Brown, Shiras, White, McKenna, JJ | ||||||

| Dissent | Harlan | ||||||

Maxwell v. Dow, 176 U.S. 581 (1900), is a United States Supreme Court decision which addressed two questions relating to the Due Process Clause. First, whether the Utah's practice of allowing prosecutors to directly file criminal charges without a grand jury (this practice goes by the confusing name of information) were consistent with due process, and second, whether Utah's use of eight jurors instead of twelve in "courts of general jurisdiction" were constitutional.

Background

The passage of the Fourteenth amendment expanded the application of the Bill of Rights to questions of state law with the Privileges or Immunities Clause which states "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States", The landmark 1876 Slaughter-House Cases, set a narrow standard for the class of rights that clause may be applied to.

At the time of the case, the laws of Utah allowed criminal charges by grand jury or by "information", and provided for variying numbers of jurors depending on the court and charges involved.[1]

Charles L. Maxwell was tried and convicted of robbery in Utah in 1898, and was eventually appealed to the Supreme Court, which heard the case in 1899.[2] His suit argued that by denying him a twelve-member jury, and by avoiding the use of a grand jury, Utah's prosecution of him had violated his incorporated Due Process Clause rights.

Opinion of the Court

Associate Justice Rufus Wheeler Peckham, writing for the majority, held that Maxwell's rights under the Due Process Clause had not been violated. Much of the decision rested on the Slaugher-House Cases precedent.[3]

Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan's lone dissent argued instead for the incorporation of the entirety of the first eight Amendments to the Constitution,[3] a position he had been the first Supreme Court Justice to articulate in his lone dissent in Hurtado v. California (1884),[4] and continued to argue in cases such as Twining v. New Jersey (1908).[5]

Subsequent developments

While the Court now incorporates a far greater portion of the Bill of Rights against the states, the specific narrow rights addressed in this case, specifically the right to a grand jury,[6] and the right to a twelve-member jury in criminal cases remain unincorporated. In particular, with regard to jury size for state criminal prosecutions, Williams v. Florida (1970), for example, held that six jurors was sufficient; Ballew v. Georgia held that five were insufficient eight years later.

See also

References

- ↑ Watson, David Kemper (1910). The Constitution of the United States: its history application and construction. Callaghan. pp. 1643–. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ Court opinion at Justia

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Church, Joan; Schulze, Christian; Strydom, Hennie (2007-01-01). Human Rights from a Comparative and International Law Perspective. Unisa Press. pp. 136–. ISBN 9781868883615. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ Lieberman, Jethro Koller (1999). A Practical Companion to the Constitution: How the Supreme Court Has Ruled on Issues from Abortion to Zoning. 1998/2008. University of California Press. pp. 245–. ISBN 9780520212800. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ Bogen, David S. (2003-04-30). Privileges and Immunities: A Reference Guide to the United States Constitution. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 117–. ISBN 9780313313479. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ Emanuel, Steven L.; Emanuel, Lazar (2008-10-31). Constitutional Law 2008. Aspen Publishers Online. pp. 68–. ISBN 9780735570542. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||