Max Schlemmer

Maximilian "Max" Joseph August Schlemmer (April 13, 1856 – 1935) known as the "King of Laysan" was a German immigrant to the United States of America who settled in Hawaii and spent fifteen years from 1894 to 1915 living with his family on the Hawaiian island of Laysan as superintendent of a guano mining operation. Schlemmer was interested in the birdlife of the island and made several studies which provide information on historic bird populations. The ecology of the island was altered by several factors including the introduction of rabbits by the family and this led to the extinction of endemic bird species such as the Laysan Rail and Laysan Millerbird at the turn of the 20th century.[1] A biography of Schlemmer was written by his grandson Tom Unger.

Early life

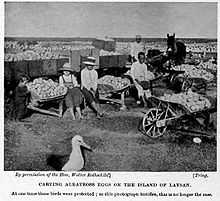

Max was born in 1856 to German parents living in Scheibenhardt, Alsace Lorraine on the border of Germany and France. He moved to New York in 1871 fearing the advance of the Prussian army into France and worked for several years abourd whaling ships before moving to Kauai in 1885 to live in a "German town" called Lihue.[2] Max worked for some years at a sugar mill and applied his mechanical skills to a small railroad system for transporting material at the mill. He married Auguste Bomke on September 5, 1886 at the Lutheran church in Lihue. Auguste had three children and after her death Max married Auguste's sister, Therese on March 22, 1895.[3] Max obtained a job in the North Pacific Phosphate and Fertilizer Company which extracted nitrate from the guano obtained from islands where birds nested in large numbers, particularly Laysan Island. Max and his family with two workers moved to the Laysan Island and were the sole humans living on it leading to the jocular epithet of "King of Laysan Island." and continued to mine guano even after the company that he worked for moved out their operations.

"King of Laysan"

Schlemmer was made superintendent of the guano operation in 1896. Soon after, he left to open a bar and boardinghouse on Kauai during which time a Japanese miner was murdered during a dispute between American and Japanese workers. In the ensuing court case, the existing superintendent was removed and Max returned to Laysan again. The North Pacific Phosphate and Fertilizer Company sold their mining rights to Schlemmer, and he in turn sold them to a Genkichi Yamanouchi of Tokyo, allowing him to export anything from Laysan. Yamanouchi used this permission to export not guano, which had been mostly depleted, but bird feathers.[4]

With the creation of the bird reservation in 1909, however, these activities became illegal, and Schlemmer was removed from the island. The rabbits that he had previously let loose now became uncontrolled and ravaged the island for food. The US Biological Survey sent a crew to exterminate them in 1913, but ran out of ammunition after 5,000 were killed, leaving a substantial number still alive. Max couldn't live away from Laysan, and in 1915 the government allowed him to return while denying his request to become a federal game warden. With nothing to eat on the bare island, Schlemmer's family nearly starved before they were rescued by the USS Nereus. With World War I having broken out and the subsequent ameri-German paranoia it cause in full effect, Schlemmer found himself falsely accused of being a German spy using Laysan as his headquarters.

Repercussions of the rabbit outbreak

Not all of the animals on Laysan were hardy enough to survive the following few years, during which time Laysan degenerated into a veritable desert devoid of vegetation. Many species became extinct in the early 1920s, including the Laysan Rail (which survived on other islands afterwards but soon became extinct there as well), the Laysan Millerbird, and the Laysan Fan Palm. The Laysan Finch was able to survive by scavenging other dead birds, and the Laysan Duck survived because its diet of brine flies was unharmed.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Dill, Homer R.; Bryan, William Alanson (1912). Report of an expedition to Laysan Island in 1911. Washington: U.S.Department of Agriculture. Biological Survey Bulletin No. 41. pp. 1–30.

- ↑ Unger:5

- ↑ Unger:23

- ↑ Ely, Charles A. and Roger B. Clapp (1973). The Natural History of Laysan Islands, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Atoll Research Bulletin No. 171. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

References

- Unger, Tom (2004). Max Schlemmer, Hawaii's King of Laysan Island. iUniverse.

- Rauzon, M. Isles of Refuge: Wildlife and History of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, 2001.

- FORUM di FILATELIA pagina 100 at www.cifr.it (most parts in Italian)

- NWHI : Research : NOWRAMP 2002 : Journals at www.hawaiianatolls.org