Maurya Empire

| Mauryan Empire | |||||

| मौर्यसाम्राज्यम् (Sanskrit) | |||||

| |||||

Maurya Empire at its maximum extent | |||||

| Capital | Pataliputra (Modern day Patna) | ||||

| Languages | Old Indic Languages (e.g. Magadhi Prakrit, Other Prakrits, Sanskrit) | ||||

| Religion | Hinduism Buddhism Jainism Ājīvika | ||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy as described in the Arthashastra | ||||

| Samraat (Emperor) | |||||

| - | 320–298 BCE | Chandragupta Maurya | |||

| - | 298–272 BCE | Bindusara | |||

| - | 268–232 BCE | Ashoka | |||

| - | 232–224 BCE | Dasaratha Maurya | |||

| - | 224–215 BCE | Samprati | |||

| - | 215–202 BCE | Salisuka Maurya | |||

| - | 202–195 BCE | Devavarman | |||

| - | 195–187 BCE | Satadhanvan | |||

| - | 187–185 BCE | Brihadratha | |||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||

| - | Established | 322 BCE | |||

| - | Disestablished | 185 BCE | |||

| Area | 5,000,000 km² (1,930,511 sq mi) | ||||

| Currency | Panas | ||||

| Today part of | | ||||

| Outline of South Asian history History of Indian subcontinent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Soanian people (500,000 BP)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stone Age (50,000–3000 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3000–1300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1200–26 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Classical period (21–1279 AD) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1596)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial period (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other states (1102–1947)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kingdoms of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nation histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Specialised histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

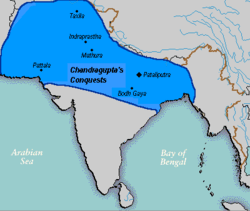

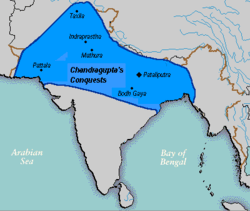

The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in ancient India, ruled by the Maurya dynasty from 322–185 BCE. Originating from the kingdom of Magadha in the Indo-Gangetic Plain (modern Bihar, eastern Uttar Pradesh) in the eastern side of the Indian subcontinent, the empire had its capital city at Pataliputra (modern Patna).[1][2] The Empire was founded in 322 BCE by Chandragupta Maurya, who had overthrown the Nanda Dynasty and rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India, taking advantage of the disruptions of local powers in the wake of the withdrawal westward by Alexander the Great's Hellenic armies. By 316 BCE the empire had fully occupied Northwestern India, defeating and conquering the satraps left by Alexander.[3] Chandragupta then defeated the invasion led by Seleucus I, a Macedonian general from Alexander's army, gaining additional territory west of the Indus River.[4]

The Maurya Empire was one of the largest empires of the world in its time. It was also the largest empire ever in the Indian subcontinent.[5] At its greatest extent, the empire stretched to the north along the natural boundaries of the Himalayas, to the east into Assam, to the west into Balochistan (south west Pakistan and south east Iran) and the Hindu Kush mountains of what is now Afghanistan.[6] The Empire was expanded into India's central and southern regions[7][8] by the emperors Chandragupta and Bindusara, but it excluded a small portion of unexplored tribal and forested regions near Kalinga (modern Odisha), until it was conquered by Ashoka.[9] It declined for about 50 years after Ashoka's rule ended, and it dissolved in 185 BCE with the foundation of the Sunga Dynasty in Magadha.

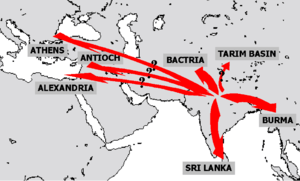

Under Chandragupta and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture and economic activities, all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security. After the Kalinga War, the Empire experienced nearly half a century of peace and security under Ashoka. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of Jainism increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism has been said to have been the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across all of India. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist ideals into Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West Asia[10] and Mediterranean Europe.[3]

The population of the empire has been estimated to be about 50 – 60 million making the Mauryan Empire one of the most populous empires of Antiquity.[11][12] Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). The Arthashastra[13] and the Edicts of Ashoka are the primary sources of written records of Mauryan times. The Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath has been made the national emblem of India.

History

Chandragupta Maurya and Chanakya

The Maurya Empire was founded by Chandragupta Maurya, with help from Chanakya, a Brahmin teacher at Takshashila. According to several legends, Chanakya traveled to Magadha, a kingdom that was large and militarily powerful and feared by its neighbors, but was insulted by its king Dhana Nanda, of the Nanda Dynasty. Chanakya swore revenge and vowed to destroy the Nanda Empire.[14] Meanwhile, the conquering armies of Alexander the Great refused to cross the Beas River and advance further eastward, deterred by the prospect of battling Magadha. Alexander returned to Babylon and re-deployed most of his troops west of the Indus river. Soon after Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BCE, his empire fragmented, and local kings declared their independence, leaving several smaller disunited satraps.

The Greek generals Eudemus, and Peithon, ruled until around 317 BCE, when Chandragupta Maurya (with the help of Chanakya, who was now his advisor) utterly defeated the Macedonians and consolidated the region under the control of his new seat of power in Magadha.[3]

Chandragupta Maurya's rise to power is shrouded in mystery and controversy. On one hand, a number of ancient Indian accounts, such as the drama Mudrarakshasa (Poem of Rakshasa – Rakshasa was the prime minister of Magadha) by Visakhadatta, describe his royal ancestry and even link him with the Nanda family. A kshatriya clan known as the Maurya's are referred to in the earliest Buddhist texts, Mahaparinibbana Sutta. However, any conclusions are hard to make without further historical evidence. Chandragupta first emerges in Greek accounts as "Sandrokottos". As a young man he is said to have met Alexander.[15] He is also said to have met the Nanda king, angered him, and made a narrow escape.[16] Chanakya's original intentions were to train a guerilla army under Chandragupta's command. The Mudrarakshasa of Visakhadutta as well as the Jaina work Parisishtaparvan talk of Chandragupta's alliance with the Himalayan king Parvatka, sometimes identified with Porus (Sir John Marshall "Taxila", p18, and al.).[17][18][19]

Conquest of Magadha

Chanakya encouraged Chandragupta Maurya and his army to take over the throne of Magadha. Using his intelligence network, Chandragupta gathered many young men from across Magadha and other provinces, men upset over the corrupt and oppressive rule of king Dhana, plus the resources necessary for his army to fight a long series of battles. These men included the former general of Taxila, accomplished students of Chanakya, the representative of King Porus of Kakayee, his son Malayketu, and the rulers of small states.

Preparing to invade Pataliputra, Maurya came up with a strategy. A battle was announced and the Magadhan army was drawn from the city to a distant battlefield to engage Maurya's forces. Maurya's general and spies meanwhile bribed the corrupt general of Nanda. He also managed to create an atmosphere of civil war in the kingdom, which culminated in the death of the heir to the throne. Chanakya managed to win over popular sentiment. Ultimately Nanda resigned, handing power to Chandragupta, and went into exile and was never heard of again. Chanakya contacted the prime minister, Rakshasas, and made him understand that his loyalty was to Magadha, not to the Nanda dynasty, insisting that he continue in office. Chanakya also reiterated that choosing to resist would start a war that would severely affect Magadha and destroy the city. Rakshasa accepted Chanakya's reasoning, and Chandragupta Maurya was legitimately installed as the new King of Magadha. Rakshasa became Chandragupta's chief advisor, and Chanakya assumed the position of an elder statesman.

-

The approximate extent of the Magadha state in the 5th century BCE.

-

The Nanda Empire at its greatest extent under Dhana Nanda c. 323 BCE.

-

The Maurya Empire when it was first founded by Chandragupta Maurya c. 320 BCE, after conquering the Nanda Empire when he was only about 20 years old.

-

Chandragupta Maurya later extended the borders of the empire southward into the Deccan Plateau c. 300 BCE.[2]

-

Ashoka the Great extended into Kalinga during the Kalinga War c. 265 BCE, and established superiority over the southern kingdoms.

- ^ Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1977), Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0436-8

- ^ Radhakumud Mookerji (1988). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (p. 39). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-0405-8.

Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta campaigned against the Macedonians when Seleucus I Nicator, in the process of creating the Seleucid Empire out of the eastern conquests of Alexander the Great, tried to reconquer the northwestern parts of India in 305 BCE. Seleucus failed (Seleucid–Mauryan war), the two rulers finally concluded a peace treaty: a marital treaty (Epigamia) was concluded, in which the Greeks offered their Princess for alliance and help from him. Chandragupta snatched the satrapies of Paropamisade (Kamboja and Gandhara), Arachosia (Kandhahar) and Gedrosia (Balochistan), and Seleucus I received 500 war elephants that were to have a decisive role in his victory against western Hellenistic kings at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE. Diplomatic relations were established and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, Deimakos and Dionysius resided at the Mauryan court.

Chandragupta established a strong centralized state with an administration at Pataliputra, which, according to Megasthenes, was "surrounded by a wooden wall pierced by 64 gates and 570 towers— (and) rivaled the splendors of contemporaneous Persian sites such as Susa and Ecbatana." Chandragupta's son Bindusara extended the rule of the Mauryan empire towards southern India. The famous Tamil poet Mamulanar of the Sangam literature described how the Deccan Plateau was invaded by the Maurya army.[20] He also had a Greek ambassador at his court, named Deimachus Strabo.

Megasthenes describes a disciplined multitude under Chandragupta, who live simply, honestly, and do not know writing:

- "The Indians all live frugally, especially when in camp. They dislike a great undisciplined multitude, and consequently they observe good order. Theft is of very rare occurrence. Megasthenes says that those who were in the camp of Sandrakottos, wherein lay 400,000 men, found that the thefts reported on any one day did not exceed the value of two hundred drachmae, and this among a people who have no written laws, but are ignorant of writing, and must therefore in all the business of life trust to memory. They live, nevertheless, happily enough, being simple in their manners and frugal. They never drink wine except at sacrifices. Their beverage is a liquor composed from rice instead of barley, and their food is principally a rice-pottage." Strabo XV. i. 53–56, quoting Megasthenes.

Bindusara

Bindusara was the son of the first Mauryan emperor Chandragupta Maurya and his queen Durdhara. During his reign, the empire expanded southwards. According to the Rajavalikatha a Jain work, the original name of this emperor was Simhasena. According to a legend mentioned in the Jain texts, Chandragupta's Guru and advisor Chanakya used to feed the emperor with small doses of poison to build his immunity against possible poisoning attempts by the enemies.[21] One day, Chandragupta not knowing about poison, shared his food with his pregnant wife queen Durdhara who was 7 days away from delivery. The queen not immune to the poison collapsed and died within few minutes. Chanakya entered the room the very time she collapsed, and in order to save the child in the womb, he immediately cut open the dead queen's belly and took the baby out, by that time a drop of poison had already reached the baby and touched its head due to which child got a permanent blueish spot (a "bindu") on his forehead. Thus, the newborn was named "Bindusara".[22]

Bindusara, just 22 year-old, inherited a large empire that consisted of what is now, Northern, Central and Eastern parts of India along with parts of Afghanistan and Baluchistan. Bindusara extended this empire to the southern part of India, as far as what is now known as Karnataka. He brought sixteen states under the Mauryan Empire and thus conquered almost all of the Indian peninsula (he is said to have conquered the 'land between the two seas' – the peninsular region between the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea). Bindusara didn't conquer the friendly Dravidian kingdoms of the Cholas, ruled by King Ilamcetcenni, the Pandyas, and Cheras. Apart from these southern states, Kalinga (modern Odisha) was the only kingdom in India that didn't form the part of Bindusara's empire. It was later conquered by his son Ashoka, who served as the viceroy of Ujjaini during his father's reign.

Bindusara's life has not been documented as well as that of his father Chandragupta or of his son Ashoka. Chanakya continued to serve as prime minister during his reign. According to the medieval Tibetan scholar Taranatha who visited India, Chanakya helped Bindusara "to destroy the nobles and kings of the sixteen kingdoms and thus to become absolute master of the territory between the eastern and western oceans."[23] During his rule, the citizens of Taxila revolted twice. The reason for the first revolt was the maladministration of Suseema, his eldest son. The reason for the second revolt is unknown, but Bindusara could not suppress it in his lifetime. It was crushed by Ashoka after Bindusara's death.

Ambassadors from the Seleucid Empire (such as Deimachus) and Egypt visited his courts. He maintained good relations with the Hellenic World.

Unlike his father Chandragupta (who at a later stage converted to Jainism), Bindusara believed in the Ajivika sect. Bindusara's guru Pingalavatsa (alias Janasana) was a Brahmin[24] of the Ajivika sect. Bindusara's wife, Queen Subhadrangi (alias Queen Aggamahesi) was a Brahmin[25] also of the Ajivika sect from Champa (present Bhagalpur district). Bindusara is accredited with giving several grants to Brahmin monasteries (Brahmana-bhatto).[26]

Bindusara died in 272 BCE (some records say 268 BCE) and was succeeded by his son Ashoka the Great.

Ashoka the Great

Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka Vardhana Maurya, son of Bindusara, was also known as Asoka, Ashoka or Ashoka The Great. (reign 272- 232 BCE)

As a young prince, Ashoka was a brilliant commander who crushed revolts in Ujjain and Taxila. As monarch he was ambitious and aggressive, re-asserting the Empire's superiority in southern and western India. But it was his conquest of Kalinga (262–261 BCE) which proved to be the pivotal event of his life. Although Ashoka's army succeeded in overwhelming Kalinga forces of royal soldiers and civilian units, an estimated 100,000 soldiers and civilians were killed in the furious warfare, including over 10,000 of Ashoka's own men. Hundreds of thousands of people were adversely affected by the destruction and fallout of war. When he personally witnessed the devastation, Ashoka began feeling remorse. Although the annexation of Kalinga was completed, Ashoka embraced the teachings of Buddhism, and renounced war and violence. He sent out missionaries to travel around Asia and spread Buddhism to other countries.

Ashoka implemented principles of ahimsa by banning hunting and violent sports activity and ending indentured and forced labor (many thousands of people in war-ravaged Kalinga had been forced into hard labor and servitude). While he maintained a large and powerful army, to keep the peace and maintain authority, Ashoka expanded friendly relations with states across Asia and Europe, and he sponsored Buddhist missions. He undertook a massive public works building campaign across the country. Over 40 years of peace, harmony and prosperity made Ashoka one of the most successful and famous monarchs in Indian history. He remains an idealized figure of inspiration in modern India.

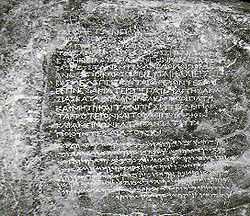

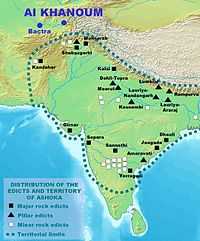

The Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, are found throughout the Subcontinent. Ranging from as far west as Afghanistan and as far south as Andhra (Nellore District), Ashoka's edicts state his policies and accomplishments. Although predominantly written in Prakrit, two of them were written in Greek, and one in both Greek and Aramaic. Ashoka's edicts refer to the Greeks, Kambojas, and Gandharas as peoples forming a frontier region of his empire. They also attest to Ashoka's having sent envoys to the Greek rulers in the West as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts precisely name each of the rulers of the Hellenic world at the time such as Amtiyoko (Antiochus), Tulamaya (Ptolemy), Amtikini (Antigonos), Maka (Magas) and Alikasudaro (Alexander) as recipients of Ashoka's proselytism. The Edicts also accurately locate their territory "600 yojanas away" (a yojanas being about 7 miles), corresponding to the distance between the center of India and Greece (roughly 4,000 miles).[27]

Decline

Ashoka was followed for 50 years by a succession of weaker kings. Brihadrata, the last ruler of the Mauryan dynasty, held territories that had shrunk considerably from the time of emperor Ashoka.

Sunga coup (185 BCE)

Brihadratha was assassinated in 185 BCE during a military parade by the Brahmin general Pushyamitra Sunga, commander-in-chief of his guard, who then took over the throne and established the Sunga dynasty. Buddhist records such as the Ashokavadana write that the assassination of Brhadrata and the rise of the Sunga empire led to a wave of religious persecution for Buddhists,[28] and a resurgence of Hinduism. According to Sir John Marshall,[29] Pushyamitra may have been the main author of the persecutions, although later Sunga kings seem to have been more supportive of Buddhism. Other historians, such as Etienne Lamotte[30] and Romila Thapar,[31] among others, have argued that archaeological evidence in favor of the allegations of persecution of Buddhists are lacking, and that the extent and magnitude of the atrocities have been exaggerated.

Establishment of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BCE)

The fall of the Mauryas left the Khyber Pass unguarded, and a wave of foreign invasion followed. The Greco-Bactrian king, Demetrius, capitalized on the break-up, and he conquered southern Afghanistan and parts of northwestern India around 180 BCE, forming the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Greeks would maintain holdings on the trans-Indus region, and make forays into central India, for about a century. Under them, Buddhism flourished, and one of their kings Menander became a famous figure of Buddhism, he was to establish a new capital of Sagala, the modern city of Sialkot. However, the extent of their domains and the lengths of their rule are subject to much debate. Numismatic evidence indicates that they retained holdings in the subcontinent right up to the birth of Christ. Although the extent of their successes against indigenous powers such as the Sungas, Satavahanas, and Kalingas are unclear, what is clear is that Scythian tribes, renamed Indo-Scythians, brought about the demise of the Indo-Greeks from around 70 BCE and retained lands in the trans-Indus, the region of Mathura, and Gujarat.

Reasons

The decline of the Maurya Dynasty was rather rapid after the death of Ashoka. One obvious reason for it was the succession of weak kings. Another immediate cause was the partition of the Empire into two. Had not the partition taken place, the Greek invasions could have been held back giving a chance to the Mauryas to re-establish some degree of their previous power. Regarding the decline much has been written. Haraprasad Sastri contends that the revolt by Pushyamitra was the result of brahminical reaction against the pro-Buddhist policies of Ashoka and pro-Jaina policies of his successors. Basing themselves on this thesis, some maintain the view that brahminical reaction was responsible for the decline because of the following reasons.

- The book Divyavadana refers to the persecution of Buddhists by Pushyamitra Sunga.

- Ashoka's claim that he exposed the Bhūdevas (Brahmins) as false gods shows that Ashoka was not well disposed towards Brahmins.

- The capture of power by Pushyamitra Sunga shows the triumph of Brahmins.

All of these three points can be challenged.

- The book Divyavadana cannot be relied upon since it was during the time of Pushyamitra Sunga that the Sanchi and Barhut stupas were completed. The impression of the persecution of Buddhism was probably created by Menander's invasion, since he was a Buddhist.

- The word 'bhūdeva' is misinterpreted because this word is to be taken in the context of some other phrase. The word normally means "brāhmaṇa" or "brahmin" in classical Sanskrit, but perhaps the context here requires it to be understood differently.

- The victory of Pushyamitra Sunga clearly shows that the last of the Mauryas was an incompetent ruler since he was overthrown in the very presence of his army, and this had nothing to do with brahminical reaction against Ashoka's patronage of Buddhism. Moreover, the very fact that a Brahmin was the commander in chief of the Mauryan ruler suggests that the Mauryas and the Brahmins were cooperating.

The question of Ashoka's religious affiliation bears reflection. He said of himself that he was a Buddhist. In his inscriptions he shows generosity to people of other religious orientations. While his doctrines follow the Buddhist Middle Path, his gifts are given to the Brahmins, Buddhist monks and others equally. His own name of adoption is Devānām Priya, the beloved of the gods.

Raychaudhury argues against the arguments of Shastri. The empire had shrunk considerably and there was no revolution. Killing the Mauryan King while he was reviewing the army points to a palace coup d'état not a revolution. The organization were ready to accept any one who could promise a more efficient organisation. Also if Pushyamitra was really a representative of brahminical reaction he neighbouting kings would have definitely given him assistance.

The argument that the empire became effete because of Ashoka's policies is also very thin. All the evidence suggests that Ashoka was a stern monarch although his reign witnessed only a single campaign. He was shrewd enough in retaining Kalinga although he expressed his remorse. Well he was worldly-wise to enslave and-and-half lakh sudras of Kalinga and bring them to the Magadha region to cut forests and cultivate land. More than this his tours of the empire were not only meant for the sake of piety but also for keeping an eye on the centrifugal tendencies of the empire. Which addressing the tribal people Ashoka expressed his willingness to for given. More draconian was Ashoka's message to the forest tribes who were warned of the power which he possessed. This view of Raychoudhury on the pacifism of the State cannot be substantiated.

Apart from these two major writers there is a third view as expressed by D. D. Kosambi. He based his arguments that unnecessary measures were taken up to increase tax and the punch-marked coins of the period show evidence of debasement. This contention too cannot be upheld. It is quite possible that debased coins began to circulate during the period of the later Mauryas. On the other hand the debasement may also indicate that there was an increased demand for silver in relation to goods leading to the silver content of the coins being reduced. More important point is the fact that the material remains of the post-Ashokan era do not suggest any pressure on the economy. Instead the economy prospered as shown by archaeological evidence at Hastinapura and Sisupalqarh. The reign of Ashoka was an asset to the economy. The unification of the country under single efficient administration the organization and increase in communications meant the development of trade as well as an opening of many new commercial interest. In the post – Ashokan period surplus wealth was used by the rising commercial classes to decorate religious buildings. The sculpture at Barhut and Sanchi and the Deccan caves was the contribution of this new bourgeoisie.

Still another view regarding of the decline of Mauryas was that the coup of Pushyamitra was a peoples' revolt against Mauryans oppression and a rejection of the Maurya adoption of foreign ideas, as far interest in Mauryan Art.

This argument is based on the view that Sunga art (Sculpture at Barhut and Sanchi) is more earthy and in the folk tradition that Maruyan art. This is more stretching the argument too far. The character of Sunga art changed because it served a different purpose and its donors belonged to different social classes. Also, Sunga art conformed more to the folk traditions because Buddhism itself had incorporated large elements of popular cults and because the donors of this art, many of whom may have been artisans, were culturally more in the mainstream of folk tradition.

One more reasoning to support the popular revolt theory is based on Ashoka's ban on the samajas. Ashoka did ban festive meetings and discouraged eating of meat. These too might have antagonized the population but it is doubtful whether these prohibitions were strictly enforced. The above argument (people's revolt) also means that Ashoka's policy was continued by his successors also, an assumption not confirmed by historical data. Further more, it is unlikely that there was sufficient national consciousness among the varied people of the Mauryan empire. It is also argued by these theorists that Ashokan policy in all its details was continued by the later Mauryas, which is not a historical fact.

Still another argument that is advanced in favour of the idea of revolt against the Mauryas is that the land tax under the Mauryas was one-quarter, which was very burden some to the cultivator. But historical evidence shows something else. The land tax varied from region to region according to the fertility of the soil and the availability of water. The figure of one quarter stated by Magasthenes probably referred only to the fertile and well-watered regions around Pataliputra.

Thus the decline of the Mauryan empire cannot be satisfactorily explained by referring to Military inactivity, Brahmin resentment, popular uprising or economic pressure. The causes of the decline were more fundamental. The organization of administration and the concept of the State were such that they could be sustained by only by kings of considerably personal ability. After the death of Ashoka there was definitely a weakening at the center particularly after the division of the empire, which inevitably led to the breaking of provinces from the Mauryan rule.

Also, it should be borne in mind that all the officials owed their loyalty to the king and not to the State. This meant that a change of king could result in change of officials leading to the demoralization of the officers. Mauryas had no system of ensuring the continuation of well-planned bureaucracy.

The next important weakness of the Mauryan Empire was its extreme centralization and the virtual monopoly of all powers by the king. There was a total absence of any advisory institution representing public opinion. That is why the Mauryas depended greatly on the espionage system. Added to this lack of representative institutions there was no distinction between the executive and the judiciary of the government. An incapable king may use the officers either for purposes of oppression or fail to use it for good purpose. And as the successors of Ashoka happened to be weak, the empire inevitably declined.

Another associated point of great importance is the fact that the Mauryan Empire which was highly centralized and autocratic was the first and last one of its kind. If the Mauryan Empire did not survive for long, it could be because of the failure of the successors of Ashoka to hold on to the principles that could make success of such an empire. Further, the Mauryan empire and the philosophy of the empire was not in tune with the spirit of the time because Aryanism and brahminism was very much there. According to the Brahmin or Aryan philosophy, the king was only an upholder of dharma, but never the crucial or architecture factor influencing the whole of life. In other words, the sentiment of the people towards the political factor, that is the State was never established in India. Such being the reality, when the successors of Ashoka failed to make use of the institution and the thinking that was needed to make a success of a centralized political authority. The Mauryan Empire declined without anyone's regret.

Other factors of importance that contributed to the decline and lack of national unity were the ownership of land and inequality of economic levels. Land could frequently change hands. Fertility wise the region of the Ganges was more prosperous than northern Deccan. Mauryan administration was not fully tuned to meet the existing disparities in economic activity. Had the southern region been more developed, the empire could have witnessed economic homogeneity.

Also the people of the sub-continent were not of uniform cultural level. The sophisticated cities and the trade centers were a great contrast to the isolated village communities. All these differences naturally led to the economic and political structures being different from region to region. It is also a fact that even the languages spoken were varied. The history of a sub-continent and their casual relationships. The causes of the decline of the Mauryan empire must, in large part, be attributed to top heavy administration where authority was entirely in the hands of a few persons while national consciousness was unknown.

Administration

The Empire was divided into four provinces, with the imperial capital at Pataliputra. From Ashokan edicts, the names of the four provincial capitals are Tosali (in the east), Ujjain (in the west), Suvarnagiri (in the south), and Taxila (in the north). The head of the provincial administration was the Kumara (royal prince), who governed the provinces as king's representative. The kumara was assisted by Mahamatyas and council of ministers. This organizational structure was reflected at the imperial level with the Emperor and his Mantriparishad (Council of Ministers).

Historians theorize that the organization of the Empire was in line with the extensive bureaucracy described by Kautilya in the Arthashastra: a sophisticated civil service governed everything from municipal hygiene to international trade. The expansion and defense of the empire was made possible by what appears to have been one of the largest armies in the world during the Iron Age.[32] According to Megasthenes, the empire wielded a military of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants alone not including tributary state allies. A vast espionage system collected intelligence for both internal and external security purposes. Having renounced offensive warfare and expansionism, Ashoka nevertheless continued to maintain this large army, to protect the Empire and instill stability and peace across West and South Asia.

Economy

For the first time in South Asia, political unity and military security allowed for a common economic system and enhanced trade and commerce, with increased agricultural productivity. The previous situation involving hundreds of kingdoms, many small armies, powerful regional chieftains, and internecine warfare, gave way to a disciplined central authority. Farmers were freed of tax and crop collection burdens from regional kings, paying instead to a nationally administered and strict-but-fair system of taxation as advised by the principles in the Arthashastra. Chandragupta Maurya established a single currency across India, and a network of regional governors and administrators and a civil service provided justice and security for merchants, farmers and traders. The Mauryan army wiped out many gangs of bandits, regional private armies, and powerful chieftains who sought to impose their own supremacy in small areas. Although regimental in revenue collection, Maurya also sponsored many public works and waterways to enhance productivity, while internal trade in India expanded greatly due to newfound political unity and internal peace.

Under the Indo-Greek friendship treaty, and during Ashoka's reign, an international network of trade expanded. The Khyber Pass, on the modern boundary of Pakistan and Afghanistan, became a strategically important port of trade and intercourse with the outside world. Greek states and Hellenic kingdoms in West Asia became important trade partners of India. Trade also extended through the Malay peninsula into Southeast Asia. India's exports included silk goods and textiles, spices and exotic foods. The external world came across new scientific knowledge and technology with expanding trade with the Mauryan Empire. Ashoka also sponsored the construction of thousands of roads, waterways, canals, hospitals, rest-houses and other public works. The easing of many over-rigorous administrative practices, including those regarding taxation and crop collection, helped increase productivity and economic activity across the Empire.

In many ways, the economic situation in the Mauryan Empire is analogous to the Roman Empire of several centuries later. Both had extensive trade connections and both had organizations similar to corporations. While Rome had organizational entities which were largely used for public state-driven projects, Mauryan India had numerous private commercial entities. These existed purely for private commerce and developed before the Mauryan Empire itself.[33] (See also Economic history of India.)

Religion

Hinduism

Hinduism was the major religion at the time of inception of the empire,[35] Hindu priests and ministers used to be an important part of the emperor's court, e.g. Chanakya. James Hastings writes that they are devotees of Narayana (Vishnu), although Shilanka speaking of the Ekandandins in another connection identifies them as Shaivas (devotees of Shiva).[36] Scholar James Hastings identifies the name "Mankhaliputta" or "Mankhali" with the bamboo staff.[36] Scholar Jitendra N. Banerjea compares them to the Pasupatas Shaivas.[37] Another scholar, Charpentier, believes that the Ajivikas worshiped Shiva before Makkhali Goshala.[38] As Chanakya wrote in his text Chanakya Niti, "Humbly bowing down before the almighty Lord Sri Vishnu, the Lord of the three worlds, I recite maxims of the science of political ethics (niti) selected from the various satras (scriptures)".[39]

Even after embracing Buddhism, Ashoka retained the membership of Hindu Brahmana priests and ministers in his court. Mauryan society began embracing the philosophy of ahimsa, and given the increased prosperity and improved law enforcement, crime and internal conflicts reduced dramatically. Also greatly discouraged was the caste system and orthodox discrimination, as Mauryans began to absorb the ideals and values of Jain and Buddhist teachings along with traditional Vedic Hindu teachings.

Buddhism

Magadha, the center of the empire, was also the birthplace of Buddhism. Ashoka initially practiced Hinduism but later embraced Buddhism; following the Kalinga War, he renounced expansionism and aggression, and the harsher injunctions of the Arthashastra on the use of force, intensive policing, and ruthless measures for tax collection and against rebels. Ashoka sent a mission led by his son Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta to Sri Lanka, whose king Tissa was so charmed with Buddhist ideals that he adopted them himself and made Buddhism the state religion. Ashoka sent many Buddhist missions to West Asia, Greece and South East Asia, and commissioned the construction of monasteries, schools and publication of Buddhist literature across the empire. He is believed to have built as many as 84,000 stupas across India i.e. Sanchi and Mahabodhi Temple, and he increased the popularity of Buddhism in Afghanistan, Thailand and North Asia including Siberia. Ashoka helped convene the Third Buddhist Council of India and South Asia's Buddhist orders, near his capital, a council that undertook much work of reform and expansion of the Buddhist religion. Indian merchants embraced Buddhism and played a large role in spreading the religion across the Mauryan Empire.[40]

Jainism

Emperor Chandragupta Maurya embraced Jainism after retiring. At an older age, Chandragupta renounced his throne and material possessions to join a wandering group of Jain monks. Chandragupta was a disciple of Acharya Bhadrabahu. It is said that in his last days, he observed the rigorous but self-purifying Jain ritual of santhara i.e. fast unto death, at Shravana Belgola in Karnataka. However, his successor, Emperor Bindusara, was a follower of another ascetic movement, Ājīvika and distanced himself from Jain and Buddhist movements. Samprati, the grandson of Ashoka also embraced Jainism. Samrat Samprati was influenced by the teachings of Jain monks and he is known to have built 125,000 derasars across India. Some of them are still found in towns of Ahmedabad, Viramgam, Ujjain & Palitana. It is also said that just like Ashoka, Samprati sent messengers & preachers to Greece, Persia & Middle East for the spread of Jainism. But to date no research has been done in this area. Thus, Jainism became a vital force under the Mauryan Rule. Chandragupta and Samprati are credited for the spread of Jainism in South India. Lakhs of temples & stupas were erected during their reign. But due to lack of royal patronage & its strict principles, along with the rise of Shankaracharya and Ramanuja, Jainism, once the major religion of southern India, began to decline.

Architectural remains

Architectural remains of the Maurya period are rather few. Remains of a hypostyle building with about 80 columns of a height of about 10 meters have been found in Kumhrar, 5 km from Patna Railway station, and is one of the very few sites that has been connected to the rule of the Mauryas. The style is rather reminiscent of Persian Achaemenid architecture.[41]

The grottoes of Barabar Caves, are another example of Mauryan architecture, especially the decorated front of the Lomas Rishi grotto. These were offered by the Mauryas to the Buddhist sect of the Ājīvikas.[42]

The most widespread example of Maurya architecture are the Pillars of Ashoka, often exquisitely decorated, with more than 40 spread throughout the Indian subcontinent.

==

The protection of animals in India became serious business by the time of the Maurya dynasty; being the first empire to provide a unified political entity in India, the attitude of the Mauryas towards forests, its denizens and fauna in general is of interest.

The Mauryas firstly looked at forests as a resource. For them, the most important forest product was the elephant. Military might in those times depended not only upon horses and men but also battle-elephants; these played a role in the defeat of Seleucus, one of Alexander's former generals. The Mauryas sought to preserve supplies of elephants since it was cheaper and took less time to catch, tame and train wild elephants than to raise them. Kautilya's Arthashastra contains not only maxims on ancient statecraft, but also unambiguously specifies the responsibilities of officials such as the Protector of the Elephant Forests.[43]

On the border of the forest, he should establish a forest for elephants guarded by foresters. The Office of the Chief Elephant Forrester should with the help of guards protect the elephants in any terrain. The slaying of an elephant is punishable by death..

The Mauryas also designated separate forests to protect supplies of timber, as well as lions and tigers, for skins. Elsewhere the Protector of Animals also worked to eliminate thieves, tigers and other predators to render the woods safe for grazing cattle.

The Mauryas valued certain forest tracts in strategic or economic terms and instituted curbs and control measures over them. They regarded all forest tribes with distrust and controlled them with bribery and political subjugation. They employed some of them, the food-gatherers or aranyaca to guard borders and trap animals. The sometimes tense and conflict-ridden relationship nevertheless enabled the Mauryas to guard their vast empire.[44]

When Ashoka embraced Buddhism in the latter part of his reign, he brought about significant changes in his style of governance, which included providing protection to fauna, and even relinquished the royal hunt. He was the first ruler in history to advocate conservation measures for wildlife and even had rules inscribed in stone edicts. The edicts proclaim that many followed the king's example in giving up the slaughter of animals; one of them proudly states:[44]

Our king killed very few animals.

However, the edicts of Ashoka reflect more the desire of rulers than actual events; the mention of a 100 'panas' (coins) fine for poaching deer in royal hunting preserves shows that rule-breakers did exist. The legal restrictions conflicted with the practices freely exercised by the common people in hunting, felling, fishing and setting fires in forests.[44]

Contacts with the Hellenistic world

Foundation of the Empire

Relations with the Hellenistic world may have started from the very beginning of the Maurya Empire. Plutarch reports that Chandragupta Maurya met with Alexander the Great, probably around Taxila in the northwest:

- "Sandrocottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth". Plutarch 62-3[45]

Reconquest of the Northwest (c. 317–316 BCE)

Chandragupta ultimately occupied Northwestern India, in the territories formerly ruled by the Greeks, where he fought the satraps (described as "Prefects" in Western sources) left in place after Alexander (Justin), among whom may have been Eudemus, ruler in the western Punjab until his departure in 317 BCE or Peithon, son of Agenor, ruler of the Greek colonies along the Indus until his departure for Babylon in 316 BCE.

- "India, after the death of Alexander, had assassinated his prefects, as if shaking the burden of servitude. The author of this liberation was Sandracottos, but he had transformed liberation in servitude after victory, since, after taking the throne, he himself oppressed the very people he has liberated from foreign domination" Justin XV.4.12–13[46]

- "Later, as he was preparing war against the prefects of Alexander, a huge wild elephant went to him and took him on his back as if tame, and he became a remarkable fighter and war leader. Having thus acquired royal power, Sandracottos possessed India at the time Seleucos was preparing future glory." Justin XV.4.19[47]

Conflict and alliance with Seleucus (305 BCE)

Seleucus I Nicator, the Macedonian satrap of the Asian portion of Alexander's former empire, conquered and put under his own authority eastern territories as far as Bactria and the Indus (Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55), until in 305 BCE he entered in a confrontation with Chandragupta:

- "Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he [Seleucus] acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus". Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55[48]

Though no accounts of the conflict remain, it is clear that Seleucus fared poorly against the Indian Emperor as he failed in conquering any territory, and in fact, was forced to surrender much that was already his. Regardless, Seleucus and Chandragupta ultimately reached a settlement and through a treaty sealed in 305 BCE, Seleucus, according to Strabo, ceded a number of territories to Chandragupta, including southern Afghanistan and parts of Persia.

Accordingly, Seleucus obtained five hundred war elephants, a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE.

Marital alliance

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married Seleucus's daughter, or a Greek Macedonian princess, a gift from Seleucus to formalize an alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500 war elephants,[49][50][51][52][53][54] a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 302 BCE. In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar state). Later Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka the Great, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[55]

Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received vast territory west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush, modern day Afghanistan, and the Balochistan province of Pakistan.[56][57] Archaeologically, concrete indications of Mauryan rule, such as the inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka, are known as far as Kandahar in southern Afghanistan.

| “ | "He (Seleucus) crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship." | ” |

| “ | "After having made a treaty with him (Sandrakotos) and put in order the Orient situation, Seleucos went to war against Antigonus." | ” |

| —Junianus Justinus, Historiarum Philippicarum libri XLIV, XV.4.15 | ||

The treaty on "Epigamia" implies lawful marriage between Greeks and Indians was recognized at the State level, although it is unclear whether it occurred among dynastic rulers or common people, or both..

Exchange of ambassadors

Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (Modern Patna in Bihar state). Later Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[55]

Exchange of presents

Classical sources have also recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus:

- "And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters [as to make people more amorous]. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love" Athenaeus of Naucratis, "The deipnosophists" Book I, chapter 32[58]

His son Bindusara 'Amitraghata' (Slayer of Enemies) also is recorded in Classical sources as having exchanged present with Antiochus I:

- "But dried figs were so very much sought after by all men (for really, as Aristophanes says, "There's really nothing nicer than dried figs"), that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus, entreating him (it is Hegesander who tells this story) to buy and send him some sweet wine, and some dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antiochus wrote to him in answer, "The dry figs and the sweet wine we will send you; but it is not lawful for a sophist to be sold in Greece" Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae" XIV.67[59]

Greek population in India

Greek population apparently remained in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Ashoka's rule. In his Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, Ashoka describes that Greek population within his realm converted to Buddhism:

- "Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma". Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika).

Fragments of Edict 13 have been found in Greek, and a full Edict, written in both Greek and Aramaic has been discovered in Kandahar. It is said to be written in excellent Classical Greek, using sophisticated philosophical terms. In this Edict, Ashoka uses the word Eusebeia ("Piety") as the Greek translation for the ubiquitous "Dharma" of his other Edicts written in Prakrit:

- "Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King Piodasses (Ashoka) made known (the doctrine of) Piety (εὐσέβεια, Eusebeia) to men; and from this moment he has made men more pious, and everything thrives throughout the whole world. And the king abstains from (killing) living beings, and other men and those who (are) huntsmen and fishermen of the king have desisted from hunting. And if some (were) intemperate, they have ceased from their intemperance as was in their power; and obedient to their father and mother and to the elders, in opposition to the past also in the future, by so acting on every occasion, they will live better and more happily". (Trans. by G.P. Carratelli )

Buddhist missions to the West (c. 250 BCE)

Also, in the Edicts of Ashoka, Ashoka mentions the Hellenistic kings of the period as a recipient of his Buddhist proselytism, although no Western historical record of this event remain:

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka)." (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in their territories:

- "Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's [Ashoka's] domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni and where the Greek king Antiochos rules, and among the kings who are neighbors of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. Wherever medical roots or fruits are not available I have had them imported and grown. Along roads I have had wells dug and trees planted for the benefit of humans and animals". 2nd Rock Edict

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek ("Yona") Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism (the Mahavamsa, XII[60]).

Subhagsena and Antiochos III (206 BCE)

Sophagasenus was an Indian Mauryan ruler of the 3rd century BCE, described in ancient Greek sources, and named Subhagsena or Subhashsena in Prakrit. His name is mentioned in the list of Mauryan princes, and also in the list of the Yadava dynasty, as a descendant of Pradyumna. He may have been a grandson of Ashoka, or Kunala, the son of Ashoka. He ruled an area south of the Hindu Kush, possibly in Gandhara. Antiochos III, the Seleucid king, after having made peace with Euthydemus in Bactria, went to India in 206 BCE and is said to have renewed his friendship with the Indian king there:

"He (Antiochus) crossed the Caucasus and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king had agreed to hand over to him". Polybius 11.39

Timeline

- 322 BC : Chandragupta Maurya founds the Mauryan Empire by overthrowing the Nanda Dynasty.

- 317–316 BC : Chandragupta Maurya conquers the Northwest of the Indian subcontinent.

- 305–303 BC : Chandragupta Maurya gains territory from the Seleucid Empire.

- 301–269 BC : Reign of Bindusara, Chandragupta's son. He conquers parts of Deccan, southern India.

- 269–232 BC : The Mauryan Empire reaches its height under Ashoka, Chandragupta's grandson.

- 261 BC : Ashoka conquers the kingdom of Kalinga.

- 250 BC : Ashoka builds Buddhist stupas and erects pillars bearing inscriptions.

- 184 BC : The empire collapses when Brihadnatha, the last emperor, is killed by Pushyamitra Sunga, a Mauryan general and the founder of the Sunga Empire.

Gallery

-

Ashoka Pillar at Lion Capital of Ashoka, which was erected around 250 BCE. It is now the emblem of India.

-

Sanchi, Stupa 1 (The Great Stupa) built by Empress Maharani Devi.

-

Uttari Toran, Northern Gate, Sanchi Stupa built by King Ashoka in 3rd century BC, which contained the relics of Buddha.

-

Asokan pillar at Vaishali

-

Kutagarasala Vihara

-

Stupa's western stairways

-

-

-

-

-

-

The distribution of the Edicts of Ashoka.[1]

- ^ Reference: "India: The Ancient Past" p.113, Burjor Avari, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-35615-6

See also

- Mauryan art

- Magadha

- Pradyota dynasty

- Nanda Dynasty

- Gupta Empire

- History of India

Notes

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India. 4th edition. Routledge, Pp. xii, 448. ISBN 0-415-32920-5.

- ↑ Thapar, Romila (1990). A History of India, Volume 1. New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. Pp. 384. ISBN 0-14-013835-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Rajadhyaksha, Abhijit (2009-08-02). "The Mauryas: Chandragupta". Historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ↑ Seleucus I ceded the territories of Arachosia (modern Kandahar), Gedrosia (modern Balochistan), and Paropamisadae (or Gandhara). Aria (modern Herat) "has been wrongly included in the list of ceded satrapies by some scholars [...] on the basis of wrong assessments of the passage of Strabo [...] and a statement by Pliny." (Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee 1996, p. 594). Seleucus "must [...] have held Aria", and furthermore, his "son Antiochos was active there fifteen years later." (Grainger 2014, p. 109).

- ↑ Chandragupta by Cristian Violatti

- ↑ The account of Strabo indicates that the western-most territory of the empire extended from the southeastern Hindu Kush, through the region of Kandahar, to coastal Balochistan to the south of that (Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee 1996, p. 594).

- ↑ Sri Lanka and the southernmost parts of India (modern Tamil Nadu and Kerala) remained independent, despite the diplomacy and cultural influence of their larger neighbor to the north (Schwartzberg 1992, p. 18; Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 68).

- ↑ The empire was once thought to have directly controlled most of the Indian subcontinent excepting the far south, but its core regions are now thought to have been separated by large tribal regions (especially in the Deccan peninsula) that were relatively autonomous. (Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 68-71, as well as Stein 1998, p. 74). "The major part of the Deccan was ruled by [Mauryan administration]. But in the belt of land on either side of the Nerbudda, the Godavari and the upper Mahanadi there were, in all probability, certain areas that were technically outside the limits of the empire proper. Ashoka evidently draws a distinction between the forests and the inhabiting tribes which are in the dominions (vijita) and peoples on the border (anta avijita) for whose benefit some of the special edicts were issued. Certain vassal tribes are specifically mentioned." (Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee pp. 275–6)

- ↑ Kalinga had been conquered by the preceding Nanda Dynasty but subsequently broke free until it was re-conquered by Ashoka, c. 260 BCE. (Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee, pp. 204–209, pp. 270–271)

- ↑ "Buddhism in Iran, Mehrak Golestan". iranian.com. 2004-12-15. Retrieved 2014-07-25.

- ↑ Boesche, Roger (2003-03-01). The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra. p. 11. ISBN 9780739106075.

- ↑ Demeny, Paul George; McNicoll, Geoffrey (May 2003). Encyclopedia of population. ISBN 9780028656793.

- ↑ "It is doubtful if, in its present shape, [the Arthashastra] is as old as the time of the first Maurya," as it probably contains layers of text ranging from Maurya times till as late as the 2nd century CE. Nonetheless, "though a comparatively late work, it may be used [...] to confirm and supplement the information gleaned from earlier sources." (Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee 1996, pp.246–7)

- ↑ Sugandhi, Namita Sanjay (2008). Between the Patterns of History: Rethinking Mauryan Imperial Interaction in the Southern Deccan. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780549744412.

- ↑

- "Androcottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth." Plutarch 62-3 Plutarch 62-3

- ↑

- "He was of humble Indian to a change of rule." Justin XV.4.15 "Fuit hic humili quidem genere natus, sed ad regni potestatem maiestate numinis inpulsus. Quippe cum procacitate sua Nandrum regem offendisset, interfici a rege iussus salutem pedum ceieritate quaesierat. (Ex qua fatigatione cum somno captus iaceret, leo ingentis formae ad dormientem accessit sudoremque profluentem lingua ei detersit expergefactumque blande reliquit. Hoc prodigio primum ad spem regni inpulsus) contractis latronibus Indos ad nouitatem regni sollicitauit." Justin XV.4.15

- ↑

- "asti tava Shaka-Yavana-Kirata-Kamboja-Parasika-Bahlika parbhutibhih

- Chankyamatipragrahittaishcha Chandergupta Parvateshvara

- balairudidhibhiriva parchalitsalilaih samantaad uprudham Kusumpurama"

- (Sanskrit original, Mudrarakshasa 2).

- ↑ The Hunas mentioned in Mudrarakshasa play (II) of Vishakhadatta are same people as the Harahunas of the Mahabharata (II.32.12). They were located in Herat/Aria according to Dr Moti Chandra and were an earlier branch of the Hunas (See: Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, p 66, Dr Moti Chandra; Also: Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, 1971, p 33, Dr D. C. Sircar.)

- ↑ For Harahunas being a group of the Hunas, see also: Early History of Iranians and Atharvaveda, Persica-9, 1980, p 118, Dr Michael Witzel, Harvard University.

- ↑ A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th century by Upinder Singh p.331

- ↑ Wilhelm Geiger (1908). The Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa and their historical development in Ceylon. Ethel M. Coomaraswamy. H. C. Cottle, Government Printer, Ceylon. p. 40. OCLC 559688590.

- ↑ M. Srinivasachariar (1989). History of classical Sanskrit literature (3 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. p. 550. ISBN 978-81-208-0284-1.

- ↑ P.109 A brief history of India by Alain Daniélou, Kenneth Hurry

- ↑ P. 138 and P. 146 History and doctrines of the Ājīvikas: a vanished Indian religion by Arthur Llewellyn Basham

- ↑ P. 24 Buddhism in comparative light by Anukul Chandra Banerjee

- ↑ P. 171 Ashoka and his inscriptions, Volume 1 by Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa

- ↑ Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, translation S. Dhammika.

- ↑ According to the Ashokavadana

- ↑ Sir John Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi", Eastern Book House, 1990, ISBN 81-85204-32-2, pg.38

- ↑ E. Lamotte: History of Indian Buddhism, Institut Orientaliste, Louvain-la-Neuve 1988 (1958)

- ↑ Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas by Romila Thapar, Oxford University Press, 1960 P200

- ↑ Gabriel A, Richard. "The Ancient World :Volume 1 of Soldiers' lives through history". 30 November 2006. Greenwood Publishing Group. p28. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ The Economic History of the Corporate Form in Ancient India. University of Michigan.

- ↑ Source: "Butkara I", Facenna.

- ↑ http://www.sfabx.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Mauryan_Empire.6185944.pdf

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 P. 266 Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 1 By James Hastings

- ↑ P. 92 Paurānic and Tāntric Religion: Early Phase By Jitendra Nath Banerjea

- ↑ P. 212 Age of the Nandas and Mauryas By K. A. Nilakanta Sastri

- ↑ Chanakya at Hinduism.co.za

- ↑ Jerry Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press), 46

- ↑ "L'age d'or de l'Inde Classique", p23

- ↑ "L'age d'or de l'Inde Classique", p22

- ↑ Rangarajan, M. (2001) India's Wildlife History, pp 7.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Rangarajan, M. (2001) India's Wildlife History, pp 8.

- ↑ Plutarch 62-3

- ↑ "(Transitum deinde in Indiam fecit), quae post mortem Alexandri, ueluti ceruicibus iugo seruitutis excusso, praefectos eius occiderat. Auctor libertatis Sandrocottus fuerat, sed titulum libertatis post uictoriam in seruitutem uerterat ; 14 siquidem occupato regno populum quem ab externa dominatione uindicauerat ipse seruitio premebat." Justin XV.4.12–13

- ↑ "Molienti deinde bellum aduersus praefectos Alexandri elephantus ferus infinitae magnitudinis ultro se obtulit et ueluti domita mansuetudine eum tergo excepit duxque belli et proeliator insignis fuit. Sic adquisito regno Sandrocottus ea tempestate, qua Seleucus futurae magnitudinis fundamenta iaciebat, Indiam possidebat." Justin XV.4.19

- ↑ Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55

- ↑

- ↑ Ancient India, (Kachroo, p.196)

- ↑ The Imperial Gazetteer of India, (Hunter, p.167)

- ↑ The evolution of man and society, (Darlington, p.223)

- ↑ W. W. Tarn (1940). "Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus' 500 Elephants, 2. Tarmita", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 60, p. 84-94.

- ↑ Partha Sarathi Bose (2003). Alexander the Great's Art of Strategy. Gotham Books. ISBN 1-59240-053-1.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", Chap. 21

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith (1998). Ashoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1303-1.

- ↑ Walter Eugene Clark (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology", Classical Philology 14 (4), p. 297-313.

- ↑ Ath. Deip. I.32

- ↑ Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae" XIV.67

- ↑ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII

References

- Chanakya, Arthashastra ISBN 0-14-044603-6

- J.F.C. Fuller, The Generalship of Alexander the Great ISBN 0-306-81330-0

- Grainger, John D. (1990, 2014). Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. Routledge.

- Keay, John (2000). India, a History. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Kulke, H.; Rothermund, D. (2004). A History of India, 4th, Routledge.

- Robert Morkot, The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Greece ISBN 0-14-051335-3

- Raychaudhuri, H. C.; Mukherjee, B. N. (1996). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. Oxford University Press.

- Schwartzberg, J. E. (1992). A Historical Atlas of South Asia. University of Oxford Press.

- Stein, Burton (1998). A History of India (1st ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mauryan Empire. |

- The Mauryan Empire at All Empires

- Livius.org: Maurya dynasty

- Mauryan Empire of India

- Extent of the Empire

- The Mauryan Empire from Britannica

- Ashoka and Buddhism

- Ashoka's Edicts

| Preceded by Nanda dynasty |

Magadha dynasties | Succeeded by Sunga dynasty |

| Middle kingdoms of India | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline and cultural period |

Northwestern India (Punjab-Sapta Sindhu) |

Indo-Gangetic Plain | Central India | Southern India | ||

| Western Gangetic Plain | Northern India (Central Gangetic Plain) |

Northeastern India | ||||

| IRON AGE | ||||||

| Culture | Late Vedic Period | Late Vedic Period (Brahmin ideology)[lower-alpha 1] |

Late Vedic Period (Kshatriya/Shramanic culture)[lower-alpha 2] |

Pre-history | ||

| 6th century BCE | Gandhara | Kuru-Panchala | Magadha | Adivasi (tribes) | ||

| Culture | Persian-Greek influences | "Second Urbanisation" Rise of Shramana movements |

Pre-history | |||

| 5th century BCE | (Persian rule) | Shishunaga dynasty | Adivasi (tribes) | |||

| 4th century BCE | (Greek conquests) |

Nanda empire |

||||

| HISTORICAL AGE | ||||||

| Culture | Spread of Buddhism | Pre-history | Sangam period (300 BCE – 200 CE) | |||

| 3rd century BCE | Maurya Empire | Early Cholas Cheras 46 other small kingdoms in Ancient Thamizhagam | ||||

| Culture | Preclassical Hinduism[lower-alpha 3] - "Hindu Synthesis"[lower-alpha 4] (ca. 200 BCE - 300 CE)[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6] Epics - Puranas - Ramayana - Mahabharata - Bhagavad Gita - Brahma Sutras - Smarta Tradition Mahayana Buddhism |

Sangam period (continued) | ||||

| 2nd century BCE | Indo-Greek Kingdom | Sunga Empire | Adivasi (tribes) | Early Cholas Cheras 46 other small kingdoms in Ancient Thamizhagam | ||

| 1st century BCE | Yona | Maha-Meghavahana Dynasty | ||||

| 1st century CE | Kuninda Kingdom | |||||

| 2nd century | Pahlava | Varman dynasty | ||||

| 3rd century | Kushan Empire | Western Satraps | Kamarupa kingdom | Kalabhras dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) | ||

| Culture | "Golden Age of Hinduism"(ca. CE 320-650)[lower-alpha 7] Puranas Co-existence of Hinduism and Buddhism | |||||

| 4th century | Gupta Empire | Kalabhras dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Kadamba Dynasty Western Ganga Dynasty | ||||

| 5th century | Maitraka | Adivasi (tribes) | Kalabhras dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) | |||

| 6th century | Kalabhras dynasty Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) | |||||

| Culture | Late-Classical Hinduism (ca. CE 650-1100)[lower-alpha 8] Advaita Vedanta - Tantra Decline of Buddhism in India | |||||

| 7th century | Indo-Sassanids | Vakataka dynasty, Harsha | Mlechchha dynasty | Adivasi (tribes) | Pandyan Kingdom(Under Kalabhras) Pandyan Kingdom(Revival) | |

| 8th century | Kidarite Kingdom | Pandyan Kingdom Kalachuri | ||||

| 9th century | Indo-Hephthalites (Huna) | Gurjara-Pratihara | Pandyan Kingdom Pandyan Kingdom(Under Cholas) Chera Perumals of Makkotai | |||

| 10th century | Pala dynasty Kamboja-Pala dynasty |

Medieval Cholas Pandyan Kingdom(Under Cholas) Chera Perumals of Makkotai Rashtrakuta | ||||

References and sources for table References Sources

| ||||||