Matroid

In combinatorics, a branch of mathematics, a matroid /ˈmeɪtrɔɪd/ is a structure that captures and generalizes the notion of linear independence in vector spaces. There are many equivalent ways to define a matroid, the most significant being in terms of independent sets, bases, circuits, closed sets or flats, closure operators, and rank functions.

Matroid theory borrows extensively from the terminology of linear algebra and graph theory, largely because it is the abstraction of various notions of central importance in these fields. Matroids have found applications in geometry, topology, combinatorial optimization, network theory and coding theory.[1][2]

Definition

There are many equivalent (cryptomorphic) ways to define a (finite) matroid.[3]

Independent sets

In terms of independence, a finite matroid  is a pair

is a pair  , where

, where  is a finite set (called the ground set) and

is a finite set (called the ground set) and  is a family of subsets of

is a family of subsets of  (called the independent sets) with the following properties:[4]

(called the independent sets) with the following properties:[4]

- The empty set is independent, i.e.,

. Alternatively, at least one subset of

. Alternatively, at least one subset of  is independent, i.e.,

is independent, i.e.,  .

. - Every subset of an independent set is independent, i.e., for each

, if

, if  then

then  . This is sometimes called the hereditary property.

. This is sometimes called the hereditary property. - If

and

and  are two independent sets of

are two independent sets of  and

and  has more elements than

has more elements than  , then there exists an element in

, then there exists an element in  that when added to

that when added to  gives a larger independent set than

gives a larger independent set than  . This is sometimes called the augmentation property or the independent set exchange property.

. This is sometimes called the augmentation property or the independent set exchange property.

The first two properties define a combinatorial structure known as an independence system.

Bases and circuits

A subset of the ground set  that is not independent is called dependent. A maximal independent set—that is, an independent set which becomes dependent on adding any element of

that is not independent is called dependent. A maximal independent set—that is, an independent set which becomes dependent on adding any element of  —is called a basis for the matroid. A circuit in a matroid

—is called a basis for the matroid. A circuit in a matroid  is a minimal dependent subset of

is a minimal dependent subset of  —that is, a dependent set whose proper subsets are all independent. The terminology arises because the circuits of graphic matroids are cycles in the corresponding graphs.[4]

—that is, a dependent set whose proper subsets are all independent. The terminology arises because the circuits of graphic matroids are cycles in the corresponding graphs.[4]

The dependent sets, the bases, or the circuits of a matroid characterize the matroid completely: a set is independent if and only if it is not dependent, if and only if it is a subset of a basis, and if and only if it does not contain a circuit. The collection of dependent sets, or of bases, or of circuits each has simple properties that may be taken as axioms for a matroid. For instance, one may define a matroid  to be a pair

to be a pair  , where

, where  is a finite set as before and

is a finite set as before and  is a collection of subsets of

is a collection of subsets of  , called "bases", with the following properties:[4]

, called "bases", with the following properties:[4]

-

is nonempty.

is nonempty. - If

and

and  are distinct members of

are distinct members of  and

and  , then there exists an element

, then there exists an element  such that

such that  . (Here the backslash symbol stands for the difference of sets. This property is called the basis exchange property.)

. (Here the backslash symbol stands for the difference of sets. This property is called the basis exchange property.)

It follows from the basis exchange property that no member of  can be a proper subset of another.

can be a proper subset of another.

Rank functions

It is a basic result of matroid theory, directly analogous to a similar theorem of bases in linear algebra, that any two bases of a matroid  have the same number of elements. This number is called the rank of

have the same number of elements. This number is called the rank of  . If

. If  is a matroid on

is a matroid on  , and

, and  is a subset of

is a subset of  , then a matroid on

, then a matroid on  can be defined by considering a subset of

can be defined by considering a subset of  to be independent if and only if it is independent in

to be independent if and only if it is independent in  . This allows us to talk about submatroids and about the rank of any subset of

. This allows us to talk about submatroids and about the rank of any subset of  . The rank of a subset A is given by the rank function r(A) of the matroid, which has the following properties:[4]

. The rank of a subset A is given by the rank function r(A) of the matroid, which has the following properties:[4]

- The value of the rank function is always a non-negative integer.

- For any subset

of

of  ,

,  .

. - For any two subsets

and

and  of

of  ,

,  . That is, the rank is a submodular function.

. That is, the rank is a submodular function. - For any set

and element

and element  ,

,  . From the first of these two inequalities it follows more generally that, if

. From the first of these two inequalities it follows more generally that, if  , then

, then  . That is, the rank is a monotonic function.

. That is, the rank is a monotonic function.

These properties can be used as one of the alternative definitions of a finite matroid: if  satisfies these properties, then the independent sets of a matroid over

satisfies these properties, then the independent sets of a matroid over  can be defined as those subsets

can be defined as those subsets  of

of  with

with  .

.

The difference  is called the nullity or corank of the subset

is called the nullity or corank of the subset  . It is the minimum number of elements that must be removed from

. It is the minimum number of elements that must be removed from  to obtain an independent set. The nullity of

to obtain an independent set. The nullity of  in

in  is called the nullity or corank of

is called the nullity or corank of  .

.

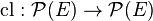

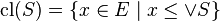

Closure operators

Let  be a matroid on a finite set

be a matroid on a finite set  , with rank function

, with rank function  as above. The closure

as above. The closure  of a subset

of a subset  of

of  is the set

is the set

.

.

This defines a closure operator  where

where  denotes the power set, with the following properties:

denotes the power set, with the following properties:

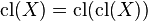

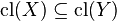

- For all subsets

of

of  ,

,  .

. - For all subsets

of

of  ,

,  .

. - For all subsets

and

and  of

of  with

with  ,

,  .

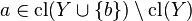

. - For all elements

, and

, and  of

of  and all subsets

and all subsets  of

of  , if

, if  then

then  .

.

The first three of these properties are the defining properties of a closure operator. The fourth is sometimes called the Mac Lane–Steinitz exchange property. These properties may be taken as another definition of matroid: every function  that obeys these properties determines a matroid.[4]

that obeys these properties determines a matroid.[4]

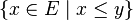

Flats

A set whose closure equals itself is said to be closed, or a flat or subspace of the matroid.[5] A set is closed if it is maximal for its rank, meaning that the addition of any other element to the set would increase the rank. The closed sets of a matroid are characterized by a covering partition property:

- The whole point set

is closed.

is closed. - If

and

and  are flats, then

are flats, then  is a flat.

is a flat. - If

is a flat, then the flats

is a flat, then the flats  that cover

that cover  (meaning that

(meaning that  properly contains

properly contains  but there is no flat

but there is no flat  between

between  and

and  ), partition the elements of

), partition the elements of  .

.

The class  of all flats, partially ordered by set inclusion, forms a matroid lattice.

Conversely, every matroid lattice

of all flats, partially ordered by set inclusion, forms a matroid lattice.

Conversely, every matroid lattice  forms a matroid over its set

forms a matroid over its set  of atoms under the following closure operator: for a set

of atoms under the following closure operator: for a set  of atoms with join

of atoms with join  ,

,

.

.

The flats of this matroid correspond one-for-one with the elements of the lattice; the flat corresponding to lattice element  is the set

is the set

.

.

Thus, the lattice of flats of this matroid is naturally isomorphic to  .

.

Hyperplanes

In a matroid of rank  , a flat of rank

, a flat of rank  is called a hyperplane. These are the maximal proper flats; that is, the only superset of a hyperplane that is also a flat is the set

is called a hyperplane. These are the maximal proper flats; that is, the only superset of a hyperplane that is also a flat is the set  of all the elements of the matroid. Hyperplanes are also called coatoms or copoints. An equivalent definition: A coatom is a subset of E that does not span M, but such that adding any other element to it does make a spanning set.[6]

of all the elements of the matroid. Hyperplanes are also called coatoms or copoints. An equivalent definition: A coatom is a subset of E that does not span M, but such that adding any other element to it does make a spanning set.[6]

The family  of hyperplanes of a matroid has the following properties, which may be taken as yet another axiomatization of matroids:[6]

of hyperplanes of a matroid has the following properties, which may be taken as yet another axiomatization of matroids:[6]

- There do not exist distinct sets

and

and  in

in  with

with  . That is, the hyperplanes form a Sperner family.

. That is, the hyperplanes form a Sperner family. - For every

and

and  with

with  , there exists

, there exists  with

with  .

.

Examples

Uniform matroids

Let E be a finite set and k a natural number. One may define a matroid on E by taking every k-element subset of E to be a basis. This is known as the uniform matroid of rank k. A uniform matroid with rank k and with n elements is denoted  . All uniform matroids of rank at least 2 are simple. The uniform matroid of rank 2 on n points is called the n-point line. A matroid is uniform if and only if it has no circuits of size less than the one plus the rank of the matroid. The direct sums of uniform matroids are called partition matroids.

. All uniform matroids of rank at least 2 are simple. The uniform matroid of rank 2 on n points is called the n-point line. A matroid is uniform if and only if it has no circuits of size less than the one plus the rank of the matroid. The direct sums of uniform matroids are called partition matroids.

In the uniform matroid  , every element is a loop (an element that does not belong to any independent set), and in the uniform matroid

, every element is a loop (an element that does not belong to any independent set), and in the uniform matroid  , every element is a coloop (an element that belongs to all bases). The direct sum of matroids of these two types is a partition matroid in which every element is a loop or a coloop; it is called a discrete matroid. An equivalent definition of a discrete matroid is a matroid in which every proper, non-empty subset of the ground set E is a separator.

, every element is a coloop (an element that belongs to all bases). The direct sum of matroids of these two types is a partition matroid in which every element is a loop or a coloop; it is called a discrete matroid. An equivalent definition of a discrete matroid is a matroid in which every proper, non-empty subset of the ground set E is a separator.

Matroids from linear algebra

Matroid theory developed mainly out of a deep examination of the properties of independence and dimension in vector spaces. There are two ways to present the matroids defined in this way:

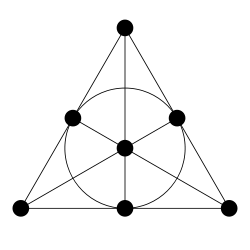

- If E is any finite subset of a vector space V, then we can define a matroid M on E by taking the independent sets of M to be the linearly independent subsets of E. The validity of the independent set axioms for this matroid follows from the Steinitz exchange lemma. If M is a matroid that can be defined in this way, we say the set E represents M. Matroids of this kind are called vector matroids. An important example of a matroid defined in this way is the Fano matroid, a rank-three matroid derived from the Fano plane, a finite geometry with seven points (the seven elements of the matroid) and seven lines (the nontrivial flats of the matroid). It is a linear matroid whose elements may be described as the seven nonzero points in a three-dimensional vector space over the finite field GF(2). However, it is not possible to provide a similar representation for the Fano matroid using the real numbers in place of GF(2).

- A matrix A with entries in a field gives rise to a matroid M on its set of columns. The dependent sets of columns in the matroid are those that are linearly dependent as vectors. This matroid is called the column matroid of A, and A is said to represent M. For instance, the Fano matroid can be represented in this way as a 3 × 7 (0,1)-matrix. Column matroids are just vector matroids under another name, but there are often reasons to favor the matrix representation. (There is one technical difference: a column matroid can have distinct elements that are the same vector, but a vector matroid as defined above cannot. Usually this difference is insignificant and can be ignored, but by letting E be a multiset of vectors one brings the two definitions into complete agreement.)

A matroid that is equivalent to a vector matroid, although it may be presented differently, is called representable or linear. If M is equivalent to a vector matroid over a field F, then we say M is representable over F ; in particular, M is real-representable if it is representable over the real numbers. For instance, although a graphic matroid (see below) is presented in terms of a graph, it is also representable by vectors over any field. A basic problem in matroid theory is to characterize the matroids that may be represented over a given field F; Rota's conjecture describes a possible characterization for every finite field. The main results so far are characterizations of binary matroids (those representable over GF(2)) due to Tutte (1950s), of ternary matroids (representable over the 3-element field) due to Reid and Bixby, and separately to Seymour (1970s), and of quaternary matroids (representable over the 4-element field) due to Geelen, Gerards, and Kapoor (2000). This is very much an open area.

A regular matroid is a matroid that is representable over all possible fields. The Vámos matroid is the simplest example of a matroid that is not representable over any field.

Matroids from graph theory

A second original source for the theory of matroids is graph theory.

Every finite graph (or multigraph) G gives rise to a matroid M(G) as follows: take as E the set of all edges in G and consider a set of edges independent if and only if it is a forest; that is, if it does not contain a simple cycle. Then M(G) is called cycle matroid. Matroids derived in this way are graphic matroids. Not every matroid is graphic, but all matroids on three elements are graphic.[7] Every graphic matroid is regular.

Other matroids on graphs were discovered subsequently:

- The bicircular matroid of a graph is defined by calling a set of edges independent if every connected subset contains at most one cycle.

- In any directed or undirected graph G let E and F be two distinguished sets of vertices. In the set E, define a subset U to be independent if there are |U| vertex-disjoint paths from F onto U. This defines a matroid on E called a gammoid:[8] a strict gammoid is one for which the set E is the whole vertex set of G.[9]

- In a bipartite graph G = (U,V,E), one may form a matroid in which the elements are vertices on one side U of the bipartition, and the independent subsets are sets of endpoints of matchings of the graph. This is called a transversal matroid,[10][11] and it is a special case of a gammoid.[8] The transversal matroids are the dual matroids to the strict gammoids.[9]

- Graphic matroids have been generalized to matroids from signed graphs, gain graphs, and biased graphs. A graph G with a distinguished linear class B of cycles, known as a "biased graph" (G,B), has two matroids, known as the frame matroid and the lift matroid of the biased graph. If every cycle belongs to the distinguished class, these matroids coincide with the cycle matroid of G. If no cycle is distinguished, the frame matroid is the bicircular matroid of G. A signed graph, whose edges are labeled by signs, and a gain graph, which is a graph whose edges are labeled orientably from a group, each give rise to a biased graph and therefore have frame and lift matroids.

- The Laman graphs form the bases of the two-dimensional rigidity matroid, a matroid defined in the theory of structural rigidity.

- Let G be a connected graph and E be its edge set. Let I be the collection of subsets F of E such that G − F is still connected. Then

is a matroid, called bond matroid of G. Note that the rank function r(F) is the number of minimal cycles in the subgraph induced on the edge subset F.

is a matroid, called bond matroid of G. Note that the rank function r(F) is the number of minimal cycles in the subgraph induced on the edge subset F.

Matroids from field extensions

A third original source of matroid theory is field theory.

An extension of a field gives rise to a matroid. Suppose F and K are fields with K containing F. Let E be any finite subset of K. Define a subset S of E to be algebraically independent if the extension field F(S) has transcendence degree equal to |S|.[12]

A matroid that is equivalent to a matroid of this kind is called an algebraic matroid.[13] The problem of characterizing algebraic matroids is extremely difficult; little is known about it. The Vámos matroid provides an example of a matroid that is not algebraic.

Basic constructions

There are some standard ways to make new matroids out of old ones.

Duality

If M is a finite matroid, we can define the orthogonal or dual matroid M* by taking the same underlying set and calling a set a basis in M* if and only if its complement is a basis in M. It is not difficult to verify that M* is a matroid and that the dual of M* is M.[14]

The dual can be described equally well in terms of other ways to define a matroid. For instance:

- A set is independent in M* if and only if its complement spans M.

- A set is a circuit of M* if and only if its complement is a coatom in M.

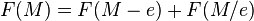

- The rank function of the dual is

.

.

According to a matroid version of Kuratowski's theorem, the dual of a graphic matroid M is a graphic matroid if and only if M is the matroid of a planar graph. In this case, the dual of M is the matroid of the dual graph of G.[15] The dual of a vector matroid representable over a particular field F is also representable over F. The dual of a transversal matroid is a strict gammoid and vice versa.

Example

The cycle matroid of a graph is the dual matroid of its bond matroid.

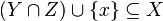

Minors

If M is a matroid with element set E, and S is a subset of E, the restriction of M to S, written M |S, is the matroid on the set S whose independent sets are the independent sets of M that are contained in S. Its circuits are the circuits of M that are contained in S and its rank function is that of M restricted to subsets of S. In linear algebra, this corresponds to restricting to the subspace generated by the vectors in S. Equivalently if T = M−S this may be termed the deletion of T, written M\T or M−T. The submatroids of M are precisely the results of a sequence of deletions: the order is irrelevant.[16][17]

The dual operation of restriction is contraction.[18] If T is a subset of E, the contraction of M by T, written M/T, is the matroid on the underlying set E − T whose rank function is  [19] In linear algebra, this corresponds to looking at the quotient space by the linear space generated by the vectors in T, together with the images of the vectors in E - T.

[19] In linear algebra, this corresponds to looking at the quotient space by the linear space generated by the vectors in T, together with the images of the vectors in E - T.

A matroid N that is obtained from M by a sequence of restriction and contraction operations is called a minor of M.[17][20] We say M contains N as a minor. Many important families of matroids may be characterized by the minor-minimal matroids that do not belong to the family; these are called forbidden or excluded minors.[21]

Sums and unions

Let M be a matroid with an underlying set of elements E, and let N be another matroid on an underlying set F. The direct sum of matroids M and N is the matroid whose underlying set is the disjoint union of E and F, and whose independent sets are the disjoint unions of an independent set of M with an independent set of N.

The union of M and N is the matroid whose underlying set is the union (not the disjoint union) of E and F, and whose independent sets are those subsets which are the union of an independent set in M and one in N. Usually the term "union" is applied when E = F, but that assumption is not essential. If E and F are disjoint, the union is the direct sum.

Additional terminology

Let M be a matroid with an underlying set of elements E.

- E may be called the ground set of M. Its elements may be called the points of M.

- A subset of E spans M if its closure is E. A set is said to span a closed set K if its closure is K.

- An element that forms a single-element circuit of M is called a loop. Equivalently, an element is a loop if it belongs to no basis.[7][22]

- An element that belongs to no circuit is called a coloop or isthmus. Equivalently, an element is a coloop if it belongs to every basis. Loop and coloops are mutually dual.[22]

- If a two-element set {f, g} is a circuit of M, then f and g are parallel in M.[7]

- A matroid is called simple if it has no circuits consisting of 1 or 2 elements. That is, it has no loops and no parallel elements. The term combinatorial geometry is also used.[7] A simple matroid obtained from another matroid M by deleting all loops and deleting one element from each 2-element circuit until no 2-element circuits remain is called a simplification of M.[23] A matroid is co-simple if its dual matroid is simple.[24]

- A union of circuits is sometimes called a cycle of M. A cycle is therefore the complement of a flat of the dual matroid. (This usage conflicts with the common meaning of "cycle" in graph theory.)

- A separator of M is a subset S of E such that

. A proper or non-trivial separator is a separator that is neither E nor the empty set.[25] An irreducible separator is a separator that contains no other non-empty separator. The irreducible separators partition the ground set E.

. A proper or non-trivial separator is a separator that is neither E nor the empty set.[25] An irreducible separator is a separator that contains no other non-empty separator. The irreducible separators partition the ground set E. - A matroid which cannot be written as the direct sum of two nonempty matroids, or equivalently which has no proper separators, is called connected or irreducible. A matroid is connected if and only if its dual is connected.[26]

- A maximal irreducible submatroid of M is called a component of M. A component is the restriction of M to an irreducible separator, and contrariwise, the restriction of M to an irreducible separator is a component. A separator is a union of components.[25]

- A matroid M is called a frame matroid if it, or a matroid that contains it, has a basis such that all the points of M are contained in the lines that join pairs of basis elements.[27]

- A matroid is called a paving matroid if all of its circuits have size at least equal to its rank.[28]

- The matroid polytope

is the convex hull of the indicator vectors of the bases of

is the convex hull of the indicator vectors of the bases of  .

.

Algorithms

Greedy algorithm

A weighted matroid is a matroid together with a function from its elements to the nonnegative real numbers. The weight of a subset of elements is defined to be the sum of the weights of the elements in the subset. The greedy algorithm can be used to find a maximum-weight basis of the matroid, by starting from the empty set and repeatedly adding one element at a time, at each step choosing a maximum-weight element among the elements whose addition would preserve the independence of the augmented set.[29] This algorithm does not need to know anything about the details of the matroid's definition, as long as it has access to the matroid through an independence oracle, a subroutine for testing whether a set is independent.

This optimization algorithm may be used to characterize matroids: if a family F of sets, closed under taking subsets, has the property that, no matter how the sets are weighted, the greedy algorithm finds a maximum-weight set in the family, then F must be the family of independent sets of a matroid.[30]

The notion of matroid has been generalized to allow for other types of sets on which a greedy algorithm give optimal solutions; see greedoid and matroid embedding for more information.

Matroid partitioning

The matroid partitioning problem is to partition the elements of a matroid into as few independent sets as possible, and the matroid packing problem is to find as many disjoint spanning sets as possible. Both can be solved in polynomial time, and can be generalized to the problem of computing the rank or finding an independent set in a matroid sum.

Matroid intersection

The intersection of two or more matroids is the family of sets that are simultaneously independent in each of the matroids. The problem of finding the largest set, or the maximum weighted set, in the intersection of two matroids can be found in polynomial time,and provides a solution to many other important combinatorial optimization problems. For instance, maximum matching in bipartite graphs can be expressed as a problem of intersecting two partition matroids. However, finding the largest set in an intersection of three or more matroids is NP-complete.

Matroid software

Two standalone systems for calculations with matroids are Kingan's Oid and Hlineny's Macek. Both of them are open sourced packages. "Oid" is an interactive, extensible software system for experimenting with matroids. "Macek" is a specialized software system with tools and routines for reasonably efficient combinatorial computations with representable matroids.

SAGE, the open source mathematics software system, will contain a matroid package from release 5.12.

Polynomial invariants

There are two especially significant polynomials associated to a finite matroid M on the ground set E. Each is a matroid invariant, which means that isomorphic matroids have the same polynomial.

Characteristic polynomial

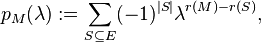

The characteristic polynomial of M (which is sometimes called the chromatic polynomial,[31] although it does not count colorings), is defined to be

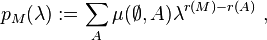

or equivalently (as long as the empty set is closed in M) as

where μ denotes the Möbius function of the geometric lattice of the matroid.[32]

When M is the cycle matroid M(G) of a graph G, the characteristic polynomial is a slight transformation of the chromatic polynomial, which is given by χG (λ) = λcpM(G) (λ), where c is the number of connected components of G.

When M is the bond matroid M*(G) of a graph G, the characteristic polynomial equals the flow polynomial of G.

When M is the matroid M(A) of an arrangement A of linear hyperplanes in Rn (or Fn where F is any field), the characteristic polynomial of the arrangement is given by pA (λ) = λn−r(M)pM(A) (λ).

Beta invariant

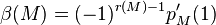

The beta invariant of a matroid, introduced by Crapo (1967), may be expressed in terms of the characteristic polynomial p as an evaluation of the derivative[33]

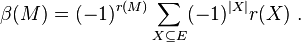

or directly as[34]

The beta invariant is non-negative, and is zero if and only if M is disconnected, or empty, or a loop. Otherwise it depends only on the lattice of flats of M. If M has no loops and coloops then β(M) = β(M∗).[34]

Tutte polynomial

The Tutte polynomial of a matroid, TM (x,y), generalizes the characteristic polynomial to two variables. This gives it more combinatorial interpretations, and also gives it the duality property

which implies a number of dualities between properties of M and properties of M *. One definition of the Tutte polynomial is

This expresses the Tutte polynomial as an evaluation of the corank-nullity or rank generating polynomial,[35]

From this definition it is easy to see that the characteristic polynomial is, up to a simple factor, an evaluation of TM, specifically,

Another definition is in terms of internal and external activities and a sum over bases, reflecting the fact that T(1,1) is the number of bases.[36] This, which sums over fewer subsets but has more complicated terms, was Tutte's original definition.

There is a further definition in terms of recursion by deletion and contraction.[37] The deletion-contraction identity is

when

when  is neither a loop nor a coloop.

is neither a loop nor a coloop.

An invariant of matroids (i.e., a function that takes the same value on isomorphic matroids) satisfying this recursion and the multiplicative condition

is said to be a Tutte-Grothendieck invariant.[35] The Tutte polynomial is the most general such invariant; that is, the Tutte polynomial is a Tutte-Grothendieck invariant and every such invariant is an evaluation of the Tutte polynomial.[31]

The Tutte polynomial TG of a graph is the Tutte polynomial TM(G) of its cycle matroid.

Infinite matroids

The theory of infinite matroids is much more complicated than that of finite matroids and forms a subject of its own. For a long time, one of the difficulties has been that there were many reasonable and useful definitions, none of which appeared to capture all the important aspects of finite matroid theory. For instance, it seemed to be hard to have bases, circuits, and duality together in one notion of infinite matroids.

The simplest definition of an infinite matroid is to require finite rank; that is, the rank of E is finite. This theory is similar to that of finite matroids except for the failure of duality due to the fact that the dual of an infinite matroid of finite rank does not have finite rank. Finite-rank matroids include any subsets of finite-dimensional vector spaces and of field extensions of finite transcendence degree.

The next simplest infinite generalization is finitary matroids. A matroid is finitary if it has the property that

Equivalently, every dependent set contains a finite dependent set. Examples are linear dependence of arbitrary subsets of infinite-dimensional vector spaces (but not infinite dependencies as in Hilbert and Banach spaces), and algebraic dependence in arbitrary subsets of field extensions of possibly infinite transcendence degree. Again, the class of finitary matroid is not self-dual, because the dual of a finitary matroid is not finitary. Finitary infinite matroids are studied in model theory, a branch of mathematical logic with strong ties to algebra.

In the late 1960s matroid theorists asked for a more general notion that shares the different aspects of finite matroids and generalizes their duality. Many notions of infinite matroids were defined in response to this challenge, but the question remained open. One of the approaches examined by D.A. Higgs became known as B-matroids and was studied by Higgs, Oxley and others in the 1960s and 1970s. According to a recent result by Bruhn, Diestel, Kriesell, Pendavingh and Wollan (2010), it solves the problem: Arriving at the same notion independently, they provided five equivalent systems of axioms – in terms of independence, bases, circuits, closure and rank. The duality of B-matroids generalizes dualities that can be observed in infinite graphs.

The independence axioms are as follows:

- The empty set is independent.

- Every subset of an independent set is independent.

- For every nonmaximal (under set inclusion) independent set I and maximal independent set J, there is

such that

such that  is independent.

is independent. - For every subset X of the base space, every independent subset I of X can be extended to a maximal independent subset of X.

With these axioms, every matroid has a dual. Also, independent sets in a Banach space form a matroid.

History

Matroid theory was introduced by Hassler Whitney (1935). It was also independently discovered by Takeo Nakasawa, whose work was forgotten for many years (Nishimura & Kuroda 2009).

In his seminal paper, Whitney provided two axioms for independence, and defined any structure adhering to these axioms to be "matroids". (Although it was perhaps implied, he did not include an axiom requiring at least one subset to be independent.) His key observation was that these axioms provide an abstraction of "independence" that is common to both graphs and matrices. Because of this, many of the terms used in matroid theory resemble the terms for their analogous concepts in linear algebra or graph theory.

Almost immediately after Whitney first wrote about matroids, an important article was written by Saunders Mac Lane (1936) on the relation of matroids to projective geometry. A year later, B. L. van der Waerden (1937) noted similarities between algebraic and linear dependence in his classic textbook on Modern Algebra.

In the 1940s Richard Rado developed further theory under the name "independence systems" with an eye towards transversal theory, where his name for the subject is still sometimes used.

In the 1950s W. T. Tutte became the foremost figure in matroid theory, a position he retained for many years. His contributions were plentiful, including the characterization of binary, regular, and graphic matroids by excluded minors; the regular-matroid representability theorem; the theory of chain groups and their matroids; and the tools he used to prove many of his results, the "Path theorem" and "Homotopy theorem" (see, e.g., Tutte 1965), which are so complex that later theorists have gone to great trouble to eliminate the necessity of using them in proofs. (A fine example is A. M. H. Gerards' short proof (1989) of Tutte's characterization of regular matroids.)

Henry Crapo (1969) and Thomas Brylawski (1972) generalized to matroids Tutte's "dichromate", a graphic polynomial now known as the Tutte polynomial (named by Crapo). Their work has recently (especially in the 2000s) been followed by a flood of papers—though not as many as on the Tutte polynomial of a graph.

In 1976 Dominic Welsh published the first comprehensive book on matroid theory.

Paul Seymour's decomposition theorem for regular matroids (1980) was the most significant and influential work of the late 1970s and the 1980s. Another fundamental contribution, by Kahn & Kung (1982), showed why projective geometries and Dowling geometries play such an important role in matroid theory.

By this time there were many other important contributors, but one should not omit to mention Geoff Whittle's extension to ternary matroids of Tutte's characterization of binary matroids that are representable over the rationals (Whittle 1995), perhaps the biggest single contribution of the 1990s. In the current period (since around 2000) the Matroid Minors Project of Jim Geelen, Gerards, Whittle, and others, which attempts to duplicate for matroids that are representable over a finite field the success of the Robertson–Seymour Graph Minors Project (see Robertson–Seymour theorem), has produced substantial advances in the structure theory of matroids. Many others have also contributed to that part of matroid theory, which (in the first and second decades of the 21st century) is flourishing.

Researchers

Mathematicians who pioneered the study of matroids include Takeo Nakasawa,[38] Saunders Mac Lane, Richard Rado, W. T. Tutte, B. L. van der Waerden, and Hassler Whitney. Other major contributors include Jack Edmonds, Jim Geelen, Eugene Lawler, László Lovász, Gian-Carlo Rota, P. D. Seymour, and Dominic Welsh.

There is an on-line list of current researchers.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Neel, David L.; Neudauer, Nancy Ann (2009). "Matroids you have known" (PDF). Mathematics Magazine 82 (1): 26–41. doi:10.4169/193009809x469020. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ Kashyap, Navin; Soljanin, Emina; Vontobel, Pascal. "Applications of Matroid Theory and Combinatorial Optimization to Information and Coding Theory" (PDF). www.birs.ca. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ A standard source for basic definitions and results about matroids is Oxley (1992). An older standard source is Welsh (1976). See Bryzlawski's appendix in White (1986) pp.298–302 for a list of equivalent axiom systems.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Welsh (1976), Section 1.2, "Axiom Systems for a Matroid", pp. 7–9.

- ↑ Welsh (1976), Section 1.8, "Closed sets = Flats = Subspaces", pp. 21–22.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Welsh (1976), Section 2.2, "The Hyperplanes of a Matroid", pp. 38–39.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Oxley 1992, p. 13

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Oxley 1992, pp. 115

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Oxley 1992, p. 100

- ↑ Oxley 1992, pp. 46–48

- ↑ 1987

- ↑ Oxley 1992, p. 215

- ↑ Oxley 1992, p. 216

- ↑ White 1986, p. 32

- ↑ White 1986, p. 105

- ↑ White 1986, p. 131

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 White 1986, p. 224

- ↑ White 1986, p. 139

- ↑ White 1986, p. 140

- ↑ White 1986, p. 150

- ↑ White 1986, pp. 146–147

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 White 1986, p. 130

- ↑ Oxley 1992, p. 52

- ↑ Oxley 1992, p. 347

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Oxley 1992, p. 128

- ↑ White 1986, p. 110

- ↑ Zaslavsky, Thomas (1994). "Frame matroids and biased graphs". Eur. J. Comb. 15 (3): 303–307. doi:10.1006/eujc.1994.1034. ISSN 0195-6698. Zbl 0797.05027.

- ↑ Oxley 1992, p. 26

- ↑ Oxley 1992, p. 63

- ↑ Oxley 1992, p. 64

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 White 1987, p. 127

- ↑ White 1987, p. 120

- ↑ White 1987, p. 123

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 White 1987, p. 124

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 White 1987, p. 126

- ↑ White 1992, p. 188

- ↑ White 1986, p. 260

- ↑ Nishimura & Kuroda (2009).

References

- Bruhn, Henning; Diestel, Reinhard; Kriesell, Matthias; Pendavingh, Rudi; Wollan, Paul (2010), Axioms for infinite matroids, arXiv:1003.3919.

- Bryant, Victor; Perfect, Hazel (1980), Independence Theory in Combinatorics, London and New York: Chapman and Hall, ISBN 0-412-22430-5.

- Brylawski, Thomas H. (1972), "A decomposition for combinatorial geometries", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society (American Mathematical Society) 171: 235–282, doi:10.2307/1996381, JSTOR 1996381.

- Crapo, Henry H. (1969), "The Tutte polynomial", Aequationes Mathematicae 3 (3): 211–229, doi:10.1007/BF01817442.

- Crapo, Henry H.; Rota, Gian-Carlo (1970), On the Foundations of Combinatorial Theory: Combinatorial Geometries, Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, ISBN 978-0-262-53016-3, MR 0290980.

- Geelen, Jim; Gerards, A. M. H.; Whittle, Geoff (2007), "Towards a matroid-minor structure theory", in Grimmett, Geoffrey (ed.) et al., Combinatorics, Complexity, and Chance: A Tribute to Dominic Welsh, Oxford Lecture Series in Mathematics and its Applications 34, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 72–82 .

- Gerards, A. M. H. (1989), "A short proof of Tutte's characterization of totally unimodular matrices", Linear Algebra and its Applications, 114/115: 207–212, doi:10.1016/0024-3795(89)90461-8.

- Kahn, Jeff; Kung, Joseph P. S. (1982), "Varieties of combinatorial geometries", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society (American Mathematical Society) 271 (2): 485–499, doi:10.2307/1998894, JSTOR 1998894.

- Kingan, Robert; Kingan, Sandra (2005), "A software system for matroids", Graphs and Discovery, DIMACS Series in Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science, pp. 287–296.

- Kung, Joseph P. S., ed. (1986), A Source Book in Matroid Theory, Boston: Birkhäuser, ISBN 0-8176-3173-9, MR 0890330.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1936), "Some interpretations of abstract linear dependence in terms of projective geometry", American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 58 (1): 236–240, doi:10.2307/2371070, JSTOR 2371070.

- Nishimura, Hirokazu; Kuroda, Susumu, eds. (2009), A lost mathematician, Takeo Nakasawa. The forgotten father of matroid theory, Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag, ISBN 978-3-7643-8572-9, MR 2516551, Zbl 1163.01001.

- Oxley, James (1992), Matroid Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-853563-5, MR 1207587, Zbl 0784.05002.

- Recski, András (1989), Matroid Theory and its Applications in Electric Network Theory and in Statics, Berlin and Budapest: Springer-Verlag and Akademiai Kiado, ISBN 3-540-15285-7, MR 1027839.

- Sapozhenko, A.A. (2001), "M/m062870", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Seymour, Paul D. (1980), "Decomposition of regular matroids", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 28 (3): 305–359, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(80)90075-1, Zbl 0443.05027.

- Truemper, Klaus (1992), Matroid Decomposition, Boston: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-701225-7, MR 1170126.

- Tutte, W. T. (1959), "Matroids and graphs", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society (American Mathematical Society) 90 (3): 527–552, doi:10.2307/1993185, JSTOR 1993185, MR 0101527.

- Tutte, W. T. (1965), "Lectures on matroids", Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards (U.S.A.), Sect. B 69: 1–47.

- Tutte, W.T. (1971), Introduction to the theory of matroids, Modern Analytic and Computational Methods in Science and Mathematics 37, New York: American Elsevier Publishing Company, Zbl 0231.05027.

- Vámos, Peter (1978), "The missing axiom of matroid theory is lost forever", Journal of the London Mathematical Society 18 (3): 403–408, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-18.3.403.

- van der Waerden, B. L. (1937), Moderne Algebra.

- Welsh, D. J. A. (1976), Matroid Theory, L.M.S. Monographs 8, Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-744050-X, Zbl 0343.05002.

- White, Neil, ed. (1986), Theory of Matroids, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications 26, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-30937-0, Zbl 0579.00001.

- White, Neil, ed. (1987), Combinatorial geometries, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications 29, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-33339-3, Zbl 0626.00007

- White, Neil, ed. (1992), Matroid Applications, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications 40, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-38165-9, Zbl 0742.00052.

- Whitney, Hassler (1935), "On the abstract properties of linear dependence", American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 57 (3): 509–533, doi:10.2307/2371182, JSTOR 2371182, MR 1507091. Reprinted in Kung (1986), pp. 55–79.

- Whittle, Geoff (1995), "A characterization of the matroids representable over GF(3) and the rationals" (PDF), Journal of Combinatorial Theory Series B 65 (2): 222–261, doi:10.1006/jctb.1995.1052.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Matroid", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Kingan, Sandra : Matroid theory. A large bibliography of matroid papers, matroid software, and links.

- Locke, S. C. : Greedy Algorithms.

- Pagano, Steven R. : Matroids and Signed Graphs.

- Mark Hubenthal: A Brief Look At Matroids (pdf) (contain proofs for staments of this article)

- James Oxley : What is a matroid?

- Neil White : Matroid Applictions