Mass racial violence in the United States

Mass racial violence in the United States, also called race riots, can include such disparate events as:

- attacks on Irish Catholics, the Chinese and other immigrants in the 19th century.

- attacks on Native Americans and Americans over the land.

- attacks on Italian immigrants in the early 20th century, and Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in the later 20th century.

- attacks on African Americans that occurred, as in 1919, in addition to the lynchings in the period after Reconstruction through the first half of the 20th century.

- frequent fighting among various ethnic groups in major cities, specifically in the northeast and midwest United States throughout the late 19th century and early 20th century. This example was made famous in the stage musical West Side Story and its film adaptation.

- unrest in African-American communities, such as the 1968 riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr..

Anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic violence

Riots defined by "race" have taken place between ethnic groups in the United States since as early as the pre-Revolution era of the 18th century. During the early-to-mid- 19th centuries, violent rioting occurred between Protestant "Nativists" and recently arrived Irish Catholic immigrants. These reached heights during the peak of immigration in the 1840s and 1850s in cities including New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. During the early 20th century, riots were common against Irish and French-Canadian immigrants in Providence, Rhode Island.

The San Francisco Vigilance Movements of 1851 and 1856 are often described by sympathetic historians as responses to rampant crime and government corruption. But, recent historians have noted that the vigilantes had a nativist bias; they systematically attacked first Irish immigrants, and later Mexicans, Chileans who came as miners during the California Gold Rush, and Chinese immigrants. During the early 20th century, racial or ethnic violence was directed by whites against Filipinos, Japanese and Armenians in California, who had arrived in waves of immigration.

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, Italian Americans were subject to racial violence. In 1891, eleven Italians were violently murdered in the streets by a large lynch mob. In the 1890s a total of twenty Italians were lynched in the South. Anti-Polish violence also occurred in the same time period.

Nineteenth-century events

Like lynchings, race riots often had their roots in economic tensions or in white defense of the color line.

In 1887, for example, ten thousand workers at sugar plantations in Louisiana, organized by the Knights of Labor, went on strike for an increase in their pay to $1.25 a day. Most of the workers were black, but some were white, infuriating Governor Samuel Douglas McEnery, who declared that "God Almighty has himself drawn the color line." The militia was called in, but withdrawn to give free rein to a lynch mob in Thibodaux. The mob killed between 20 and 300 blacks. A black newspaper described the scene:

- " 'Six killed and five wounded' is what the daily papers here say, but from an eye witness to the whole transaction we learn that no less than thirty-five Negroes were killed outright. Lame men and blind women shot; children and hoary-headed grandsires ruthlessly swept down! The Negroes offered no resistance; they could not, as the killing was unexpected. Those of them not killed took to the woods, a majority of them finding refuge in this city."[1]

In 1891, a mob lynched Joe Coe, a black worker in Omaha, Nebraska suspected of attacking a young white woman from South Omaha. Approximately 10,000 white people, mostly ethnic immigrants from South Omaha, reportedly swarmed the courthouse and took Coe from his jail cell, beating and then lynching him. Reportedly 6,000 people visited Coe's corpse during a public exhibition at which pieces of the lynching rope were sold as souvenirs. This was a period when even officially sanctioned executions, such as hangings, were regularly conducted in public.[2]

Twentieth-century events

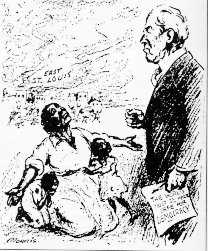

Labor and immigrant conflict was a source of tensions that catalyzed into the East St. Louis riot of 1917. White rioters, many of them ethnic immigrants, killed an estimated 100 black residents of East St. Louis, after black residents had killed two white policemen, mistaking the car they were riding in for a previous car of white occupants who drove through a black neighborhood and fired randomly into a crowd of blacks.

White-on-Black race riots include the Atlanta riots (1906), the Omaha and Chicago riots (1919), part of a series of riots in the volatile post-World War I environment, and the Tulsa Riots (1921).

The Chicago race riot of 1919 grew out of tensions on the Southside, where Irish descendants and African Americans competed for jobs at the stockyards, and where both were crowded into substandard housing. The Irish descendants had been in the city longer, and were organized around athletic and political clubs.

A young black Chicagoan, Eugene Williams, paddled a raft near a Southside Lake Michigan beach into "white territory", and drowned after being hit by a rock thrown by a young white man. Witnesses pointed out the killer to a policeman, who refused to make an arrest. An indignant black mob attacked the officer.[3] Violence broke out across the city. White mobs, many of them organized around Irish athletic clubs, began pulling black people off trolley cars, attacking black businesses, and beating victims with baseball bats and iron bars. Having learned from the East St. Louis riot, the city closed down the street car system, but the rioting continued. A total of 23 blacks and 15 whites were killed.[4]

The 1921 Tulsa race riot grew out of economic competition, as the black Greenwood area was compared to Wall Street, and filled with independent businesses. In the immediate event, blacks resisted whites who tried to lynch 19-year old Dick Rowland, who worked at shoeshines. Thirty-nine people (26 black, 13 white) were confirmed killed. An early 21st century investigation of these events has suggested that the number of casualties could be much higher. White mobs set fire to the black Greenwood district, destroying 1,256 homes and as many as 200 businesses. Fires leveled 35 blocks of residential and commercial neighborhood. Black people were rounded up by the Oklahoma National Guard and put into several internment centers, including a baseball stadium. White rioters in airplanes shot at black refugees and dropped improvised kerosene bombs and dynamite on them.[5]

By the 1960s, decades of racial, economic, and political forces, which generated inner city poverty, resulted in "race riots" within minority areas in cities across the United States. The beating and rumored death of cab driver John Smith by police, sparked the 1967 Newark riots. This event became, per capita, one of the deadliest civil disturbances of the 1960s. The long and short term causes of the Newark riots are explored in depth in the documentary film Revolution '67. The assassinations of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee and later of Robert Kennedy in Los Angeles in 1968 also led to rioting.

The 1980s and '90s saw a number of riots tied to longstanding racial tensions between police and minority communities. The 1980 Miami riots occurred following the death of an African-American motorist at the hands of four white Miami-Dade Police officers who were subsequently acquitted on charges of manslaughter and evidence tampering. Similarly, the six-day 1992 Los Angeles riots erupted after the acquittal of four white LAPD officers who had been filmed beating Rodney King, an African-American motorist. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, the Director of the Harlem-based Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has identified over 100 instances of mass racial violence in the United States since 1935 and has noted that almost every instance was precipitated by a police incident.[6]

Twenty-first-century events

The trend from the late 20th century continued with unrest due to perceived unfair policing of minority communities. The Cincinnati riots of 2001 were caused by the killing of 19-year-old African-American Timothy Thomas by white police officer Stephen Roach, who was subsequently acquitted on charges of negligent homicide.[7] The 2014 Ferguson unrest occurred against a backdrop of racial tension between police and the black community of Ferguson, Missouri in the wake of the shooting of Michael Brown; similar incidents elsewhere such as the shooting of Trayvon Martin sparked smaller and isolated protests. According to the Associated Press' annual poll of United States news directors and editors, the top news story of 2014 was police killings of unarmed blacks—including the shooting of Michael Brown—as well as their investigations and the protests in their aftermath.[8][9]

Timeline of events

Nativist period 1700s–1860

- for information about riots worldwide, see List of riots.

- 1829: Cincinnati riot of 1829 (Cincinnati, Ohio)

- Rioting against African Americans results in thousands leaving for Canada.

- 1829: Charlestown anti-Catholic riots (Charlestown, Massachusetts)

- 1834: Massachusetts Convent Burning

- 1835: Five Points Riot (New York City)

- 1841: Cincinnati riot of 1841 (Cincinnati, Ohio)

- 1844: Philadelphia Nativist Riots (May 6–8/July 5–8)

- 1851: Hoboken anti-German riot

- 1855: Bloody Monday (Louisville, KY Anti-German riots)

Civil War period 1861–1865

- 1863: Detroit race riot

- 1863: New York City Draft Riot

Post–Civil War and Reconstruction period: 1865–1889

- 1866: New Orleans Riot (New Orleans, Louisiana)

- 1866: Memphis Riots of 1866 (Memphis, Tennessee)

- 1868: Pulaski Riot (Pulaski, Tennessee)

- 1868: Opelousas Massacre (Opelousas, Louisiana)

- 1868: Camilla, Georgia

- 1868: Ward Island riot

- Irish and German-American indigent immigrants, temporarily interned at Wards Island by the Commissioners of Emigration, begin rioting following an altercation between two residents, resulting in thirty men seriously wounded and around sixty arrested.[10]

- 1870: Eutaw, Alabama

- 1870: Laurens, South Carolina

- 1870: Kirk-Holden war: Alamance County, North Carolina

- Federal troops, led by Col. Kirk and requested by NC governor Holden, were sent to extinguish racial violence. Holden was eventually impeached because of the offensive.

- 1870: New York City Orange Riot

- 1871: Meridian race riot of 1871, Mississippi

- 1871: Second New York City Orange Riot

- 1871: Los Angeles Anti-Chinese Riot

- 1871: Scranton coal riot

- Violence occurs between striking members of a miners' union in Scranton, Pennsylvania when Welsh miners attack Irish and German-American miners who chose to leave the union and accept the terms offered by local mining companies.[11]

- 1873: Colfax massacre (Colfax, Louisiana)

- 1874: Vicksburg, Mississippi

- 1874: New Orleans, Louisiana

- 1874: Coushatta massacre, Coushatta, Louisiana

- 1875: Yazoo City, Mississippi

- 1875: Clinton, Mississippi

- 1876: Statewide violence in South Carolina

- 1876: Hamburg, South Carolina

- 1876: Ellenton, South Carolina

- 1885: Rock Springs massacre, Wyoming

- 1886: Pittsburgh Riot

- 1887: Denver riot of 1887

- In one of the largest civil disturbances in the city's history, fighting between Swedish, Hungarian and Polish immigrants results in the shooting death of one man and injuring several others before broken up by police.[12]

- 1887: Thibodaux massacre, Thibodaux, Louisiana—strike of 10,000 sugar-cane workers which led to a mass killing of an estimated 50 African Americans

Jim Crow period: 1890–1914

- 1891: New Orleans anti-Italian riot

- A lynch mob storms a local jail and hangs several Italians following the acquittal of several Sicilian immigrants alleged to be involved in the murder of New Orleans police chief David Hennessy.

- 1891: 1st Omaha Race Riot

- 10,000 white people storm the local courthouse to beat and lynch Joe Coe, who was alleged to have raped a white child.

- 1894: Buffalo, NY riot of 1894

- Two groups of Irish and Italian-Americans are arrested by police after a half hour of hurling bricks and shooting at each other resulting from a barroom brawl when visiting Italian patrons refused to pay for their drinks at a local saloon. After the mob is dispersed by police, five Italians are arrested while two others are sent to a local hospital.[13]

- 1894: Bituminous Coal Miners' Strike

- Much of the violence in this national strike was not specifically racial, but in Iowa, where the employees of Consolidation Coal Company (Iowa) refused to join the strike, armed confrontation between strikers and strike breakers took on racial overtones because the majority of Consolidation's employees were African American. The National Guard was mobilized just in time to avert open warfare.[14][15][16]

- 1898: Wilmington Race Riot

- 1898: Lake City, South Carolina

- 1898: Greenwood County, South Carolina

- 1899: Newburg, NY riot

- Angered towards the recent hiring of African-American workers, a group of between 80 and 100 Arab laborers attack a group of African-American workers near the Freeman & Hammond brick yard with numerous men injured on both sides.[17]

- 1900: New Orleans, Louisiana : Robert Charles Riots

- 1900: New York City

- 1902: New York City

- Anti-Semitic riots involving Irish factory workers, city policemen and thousands of Jews attending Jacob Joseph's funeral

- 1906: Little Rock, Arkansas

- Started when a white police officer in Argenta killed a black musician in a bathroom, causing the burning down of half a block of burned down commercial buildings and two black residencies, as well as the departure of many blacks as white men taking arms ran down the street.[18]

- 1906: Atlanta Riots, Georgia

- 1907: Bellingham Riots, Washington

- 1908: Springfield, Illinois

- 1909: Greek Town Riot

- A successful Greek immigrant community in South Omaha, Nebraska is burnt to the ground and its residents are forced to leave town.[19]

- 1910: Nationwide riots following the heavyweight championship fight between Jack Johnson and Jim Jeffries in Reno, Nevada on July 4

War and Inter-War period: 1914–1945

- 1917: East St. Louis, Illinois

- 1917: Chester, Pennsylvania

- 1917: Philadelphia

- 1917: Houston riot

- Red Summer of 1919

- 1919: Washington, D.C.

- 1919: Chicago

- 1919: Omaha, Nebraska

- 1919: Charleston, South Carolina

- 1919: Longview, Texas

- 1919: Knoxville, Tennessee

- 1919: Elaine, Arkansas

- 1921: Tulsa, Oklahoma

- 1923: Rosewood, Florida (area is now an outgrowth of Cedar Key, Florida)

- 1927: Poughkeepsie, New York – A wave of civil unrest, violence and vandalism by local White mobs against Blacks, as well Greek, Jewish, Chinese and Puerto Rican targets in the community, though mostly directed at African-Americans.

- 1930: Watsonville, California

- 1935: Harlem race riot

- 1943: Detroit race riot

- 1943: Harlem race riot

- 1943: Zoot Suit Riots, Los Angeles

- 1944: Agana race riot, Guam

Civil Rights Movement and Black Power period: 1955–1977

1964

- Rochester 1964 race riot; Rochester, New York – July

- New York City 1964 riot; New York City – July

- Philadelphia 1964 race riot; Philadelphia – August

- Jersey City 1964 race riot, August 2–4, Jersey City, New Jersey

- Paterson 1964 race riot, August 11–13, Paterson, New Jersey

- Elizabeth 1964 race riot, August 11–13, Elizabeth, New Jersey

- Chicago 1964 race riot, Dixmoor riot, August 16–17, Chicago

1965

- Watts riots; Los Angeles, California – August

1966

- Hough Riots; Cleveland, Ohio – July

- Hunter's Point Riot; San Francisco

- Division Street Riots; Chicago – June

1967

- 1967 Newark riots; Newark, New Jersey – July

- 1967 Plainfield riots; Plainfield, New Jersey – July

- 12th Street riot; Detroit, Michigan – July

- 1967 New York City riot; Harlem, New York City - July

- Cambridge riot of 1967; Cambridge, Maryland - July

- 1967 Rochester riot; Rochester, New York - July

- 1967 Pontiac riot; Pontiac, Michigan - July

- 1967 Toledo riot; Toledo, Ohio - July

- 1967 Flint riot; Flint, Michigan - July

- 1967 Grand Rapids riot; Grand Rapids, Michigan - July

- 1967 Houston riot; Houston, Texas - July

- 1967 Englewood riot; Englewood, New Jersey - July

- 1967 Tucson riot; Tucson, Arizona - July

- Milwaukee riot; Milwaukee, Wisconsin – July 30–31

- Minneapolis North Side Riots; Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota – August

1968

- Orangeburg massacre; Orangeburg, South Carolina – February

- King assassination riots: 125 cities in April and May, in response to the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. including:

- Baltimore riot of 1968; Baltimore Maryland

- 1968 Washington, D.C. riots; Washington, D.C.

- 1968 New York City riot; New York City

- West Side Riots; Chicago

- 1968 Detroit riot; Detroit, Michigan

- Louisville riots of 1968; Louisville, Kentucky

- Hill District MLK riots; Pittsburgh, PA

- Summit, Illinois Race Riot at Argo High School, September 1968

- 1968 Democratic National Convention

1969

- 1969 York Race Riot; York, Pennsylvania – July

1970

- May 11th Augusta Race Riot; Augusta, Georgia – May

- Jackson State killings; Jackson, Mississippi – May

- Asbury Park Riot; Asbury Park, New Jersey – July

- Chicano Moratorium, an anti Vietnam War protest turned riot in East Los Angeles – August

1971

- Camden Riots, August 1971, Camden, New Jersey

1972

- Escambia High School riots; Pensacola, Florida

1973

- Santos Rodriguez riot, Dallas, Texas July 28, 1973. Riot after the March For Justice protesting Police Murder of Santos Rodríguez

1974–1988

- Boston busing crisis

1977

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

Since 1980

- 1980: Miami Riot 1980 – following the acquittal of four Miami-Dade Police officers in the death of Arthur McDuffie. McDuffie, an African-American, died from injuries sustained at the hands of four white officers trying to arrest him after a high-speed chase.

- 1991: Crown Heights Riot – May – between African Americans and the area's large Hasidic Jewish community, over the accidental killing of a Guyanese immigrant child by an Orthodox Jewish motorist. In its wake, several Jews were seriously injured; one Orthodox Jewish man, Yankel Rosenbaum, was killed; and a non-Jewish man, allegedly mistaken by rioters for a Jew, was killed by a group of African-American men.

- 1991: Overtown, Miami – In the heavily Black section against Cuban Americans, like earlier riots there in 1982 and 1984.

- 1992: 1992 Los Angeles riots – April 29 to May 5 – a series of riots, lootings, arsons and civil disturbance that occurred in Los Angeles County, California in 1992, following the acquittal of police officers on trial regarding the assault of Rodney King.

- 1992: Harlem, Manhattan in New York City – July – involved Blacks and Puerto Ricans against the New York Police Department, around the time of the 1992 Democratic National Convention being held there.

- 1995: St. Petersburg, Florida riot of 1996, caused by protests against racial profiling and police brutality.

- 2001: 2001 Cincinnati Riots – April – in the African-American section of Over-the-Rhine.

- 2005: Toledo, Ohio – Neo-Nazis and white supremacists marched in North Park, a mostly African-American section of town.

- 2009: Oakland, CA – Riots following the BART Police shooting of Oscar Grant.

- 2014: 2014 Ferguson unrest – Riots following the Shooting of Michael Brown

- 2015: 2015 Baltimore riots - Riots following the death of Freddie Gray

See also

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of race riots

- List of United States military history events

- Timeline of riots and civil unrest in Omaha, Nebraska

- World timeline of race riots

References

- ↑ Zinn, 2004;, retrieved March 27, 2009.

- ↑ Bristow, D.L. (2002) A Dirty, Wicked Town. Caxton Press. p 253.

- ↑ Chicago Daily Tribune, History Matters, George Mason University

- ↑ Dray, 2002.

- ↑ Ellsworth, Scott. The Tulsa Race Riot, retrieved July 23, 2005.

- ↑ Hannah-Jones, Nikole (2015-03-04). "Yes, Black America Fears the Police. Here’s Why.". ProPublica. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/27/us/cincinnati-officer-is-acquitted-in-killing-that-ignited-unrest.html

- ↑ "Shootings by Police Voted Top Story of 2014 in AP Poll". Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ↑ "AP poll: Police killings of blacks voted top story of 2014". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Riot On Ward's Island.; Terrific Battle Between German and Irish Emigrants"], New York Times, 06 March 1868

- ↑ "The Coal Riot. Horrible Treatment of the Laborers by the Miners. – Condition of the Wounded – A War of Races – Welsh vs. Irish and Germans," New York Times, 11 May 1871

- ↑ A Race Riot In Denver.; One Man Killed And A Number Of Heads Broken. New York Times. 12 Apr 1887

- ↑ Race Riot In Buffalo.; Italians and Irish Fight for an Hour and a Half in the Street. New York Times. 19 Mar. 1894

- ↑ Thomas J. Hudson, Iowa Chapter VIII, Events from Jackson to Cummins, The Province and the States, Vol. V, the Western Historical Association, 1904; page 170

- ↑ The Natioinal Guard – Iowa's Splendid Militia, The Midland Monthly, Vol. II, No. 5 Nov. 1894; page 419.

- ↑ Service at Muchakinock and Evans, in Mahaska County, During the Coal Miners' Strike, Report of the Ajutant-General to the Governor of the State of Iowa for Biennial Period Ending Nov. 30, 1895, Conway, Des Moines, 1895; page 18

- ↑ Race Riots In Newburg.; Negroes Employed in Brick Yards Provoke Other Laborers -- Lively Battle Between the Factions. New York Times. 29 Jul. 1899

- ↑ "Argenta Race Riot", Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture (accessed April 28, 2011).

- ↑ Larsen, L. & Cotrell, B. (1997). The gate city: A history of Omaha. University of Nebraska Press. P 163.

Further reading

- Dray, Philip. At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, New York: Random House, 2002.

- Ifill, Sherrilyn A. On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-first Century (Beacon Press, 2007) ISBN 978-0-8070-0987-1

- Sowell, Thomas. Ethnic America: A History. Copyright 1981: Basic Books, Inc.

- Zinn, Howard. Voices of a People's History of the United States. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2004.

External links

- Revolution '67 – Documentary about the Newark, New Jersey race riots of 1967

- Uprisings Urban riots of the 1960s.

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture