Mass balance

A mass balance, also called a material balance, is an application of conservation of mass to the analysis of physical systems. By accounting for material entering and leaving a system, mass flows can be identified which might have been unknown, or difficult to measure without this technique. The exact conservation law used in the analysis of the system depends on the context of the problem, but all revolve around mass conservation, i.e. that matter cannot disappear or be created spontaneously.[1]:59–62

Therefore, mass balances are used widely in engineering and environmental analyses. For example, mass balance theory is used to design chemical reactors, to analyse alternative processes to produce chemicals, as well as to model pollution dispersion and other processes of physical systems. Closely related and complementary analysis techniques include the population balance, energy balance and the somewhat more complex entropy balance. These techniques are required for thorough design and analysis of systems such as the refrigeration cycle.

In environmental monitoring the term budget calculations is used to describe mass balance equations where they are used to evaluate the monitoring data (comparing input and output, etc.) In biology the dynamic energy budget theory for metabolic organisation makes explicit use of mass and energy balances.

Introduction

The general form quoted for a mass balance is The mass that enters a system must, by conservation of mass, either leave the system or accumulate within the system .

Mathematically the mass balance for a system without a chemical reaction is as follows:[1]:59–62

Strictly speaking the above equation holds also for systems with chemical reactions if the terms in the balance equation are taken to refer to total mass, i.e. the sum of all the chemical species of the system. In the absence of a chemical reaction the amount of any chemical species flowing in and out will be the same; this gives rise to an equation for each species present in the system. However, if this is not the case then the mass balance equation must be amended to allow for the generation or depletion (consumption) of each chemical species. Some use one term in this equation to account for chemical reactions, which will be negative for depletion and positive for generation. However, the conventional form of this equation is written to account for both a positive generation term (i.e. product of reaction) and a negative consumption term (the reactants used to produce the products). Although overall one term will account for the total balance on the system, if this balance equation is to be applied to an individual species and then the entire process, both terms are necessary. This modified equation can be used not only for reactive systems, but for population balances such as arise in particle mechanics problems. The equation is given below; note that it simplifies to the earlier equation in the case that the generation term is zero.[1]:59–62

- In the absence of a nuclear reaction the number of atoms flowing in and out must remain the same, even in the presence of a chemical reaction.

- For a balance to be formed, the boundaries of the system must be clearly defined.

- Mass balances can be taken over physical systems at multiple scales.

- Mass balances can be simplified with the assumption of steady state, in which the accumulation term is zero.

Illustrative example

A simple example can illustrate the concept. Consider the situation in which a slurry is flowing into a settling tank to remove the solids in the tank. Solids are collected at the bottom by means of a conveyor belt partially submerged in the tank, and water exits via an overflow outlet.

In this example, there are two substances: solids and water. The water overflow outlet carries an increased concentration of water relative to solids, as compared to the slurry inlet, and the exit of the conveyor belt carries an increased concentration of solids relative to water.

Assumptions

- Steady state

- Non-reactive system

Analysis

Suppose that the slurry inlet composition (by mass) is 50% solid and 50% water, with a mass flow of 100 kg/min. The tank is assumed to be operating at steady state, and as such accumulation is zero, so input and output must be equal for both the solids and water. If we know that the removal efficiency for the slurry tank is 60%, then the water outlet will contain 20 kg/min of solids (40% times 100 kg/min times 50% solids). If we measure the flow rate of the combined solids and water, and the water outlet is shown to be 60 kg/min, then the amount of water exiting via the conveyor belt must be 10 kg/min. This allows us to completely determine how the mass has been distributed in the system with only limited information and using the mass balance relations across the system boundaries.

Mass feedback (recycle)

Mass balances can be performed across systems which have cyclic flows. In these systems output streams are fed back into the input of a unit, often for further reprocessing.[1]:97–105

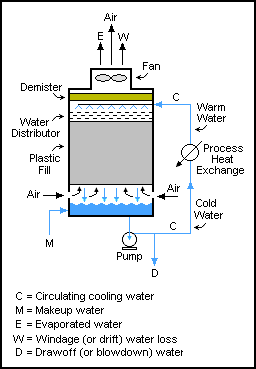

Such systems are common in grinding circuits, where materials are crushed then sieved to only allow a particular size of particle out of the circuit and the larger particles are returned to the grinder. However, recycle flows are by no means restricted to solid mechanics operations; they are used in liquid and gas flows, as well. One such example is in cooling towers, where water is pumped through a tower many times, with only a small quantity of water drawn off at each pass (to prevent solids build up) until it has either evaporated or exited with the drawn off water.

The use of the recycle aids in increasing overall conversion of input products, which is useful for low per-pass conversion processes (such as the Haber process).

Differential mass balances

A mass balance can also be taken differentially. The concept is the same as for a large mass balance, but it is performed in the context of a limiting system (for example, one can consider the limiting case in time or, more commonly, volume). A differential mass balance is used to generate differential equations that can provide an effective tool for modelling and understanding the target system.

The differential mass balance is usually solved in two steps: first, a set of governing differential equations must be obtained, and then these equations must be solved, either analytically or, for less tractable problems, numerically.

The following systems are good examples of the applications of the differential mass balance:

- Ideal (stirred) Batch reactor

- Ideal tank reactor, also named Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR)

- Ideal Plug Flow Reactor (PFR)

Ideal batch reactor

The ideal completely mixed batch reactor is a closed system. Isothermal conditions are assumed, and mixing prevents concentration gradients as reactant concentrations decrease and product concentrations increase over time.[2]:40–41 Many chemistry textbooks implicitly assume that the studied system can be described as a batch reactor when they write about reaction kinetics and chemical equilibrium. The mass balance for a substance A becomes

where rA denotes the rate at which substance A is produced, V is the volume (which may be constant or not), nA the number of moles (n) of substance A.

In a fed-batch reactor some reactants/ingredients are added continuously or in pulses (compare making porridge by either first blending all ingredients and then letting it boil, which can be described as a batch reactor, or by first mixing only water and salt and making that boil before the other ingredients are added, which can be described as a fed-batch reactor). Mass balances for fed-batch reactors become a bit more complicated.

Reactive example

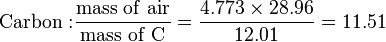

In the first example, we will show how to use a mass balance to derive a relationship between the percent excess air for the combustion of a hydrocarbon-base fuel oil and the percent oxygen in the combustion product gas. First, normal dry air contains 0.2095 mol of oxygen per mole of air, so there is one mole of O

2 in 4.773 mol of dry air. For stoichiometric combustion, the relationships between the mass of air and the mass of each combustible element in a fuel oil are:

Considering the accuracy of typical analytical procedures, an equation for the mass of air per mass of fuel at stoichiometric combustion is:

where wC, wH, wS, and wO refer to the mass fraction of each element in the fuel oil, sulfur burning to SO2, and AFRmass refers to the air-fuel ratio in mass units.

For 1 kg of fuel oil containing 86.1% C, 13.6% H, 0.2% O, and 0.1% S the stoichiometric mass of air is 14.56 kg, so AFR = 14.56. The combustion product mass is then 15.56 kg. At exact stoichiometry, O

2 should be absent. At 15 percent excess air, the AFR = 16.75, and the mass of the combustion product gas is 17.75 kg, which contains 0.505 kg of excess oxygen. The combustion gas thus contains 2.84 percent O

2 by mass. The relationships between percent excess air and %O

2 in the combustion gas are accurately expressed by quadratic equations, valid over the range 0–30 percent excess air:

In the second example we will use the law of mass action to derive the expression for a chemical equilibrium constant.

Assume we have a closed reactor in which the following liquid phase reversible reaction occurs:

The mass balance for substance A becomes

As we have a liquid phase reaction we can (usually) assume a constant volume and since  we get

we get

or

In many text books this is given as the definition of reaction rate without specifying the implicit assumption that we are talking about reaction rate in a closed system with only one reaction. This is an unfortunate mistake that has confused many students over the years.

According to the law of mass action the forward reaction rate can be written as

![r_1=k_1 [\mathrm{A}]^a[\mathrm{B}]^b](../I/m/8c6dd87ba0e3574253debc1c73257e65.png)

and the backward reaction rate as

![r_{-1}=k_{-1}1 [\mathrm{C}]^c[\mathrm{D}]^d](../I/m/59e734c2758146f4ef4ff909fc3babd3.png)

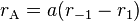

The rate at which substance A is produced is thus

and since, at equilibrium, the concentration of A is constant we get

or, rearranged

![\frac{k_1}{k_{-1}}=\frac{[\mathrm{C}]^c[\mathrm{D}]^d}{[\mathrm{A}]^a[\mathrm{B}]^b}=K_{eq}](../I/m/c90c83612b269d8faab12714258c4cdd.png)

Ideal tank reactor/continuously stirred tank reactor

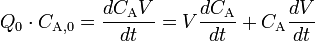

The continuously mixed tank reactor is an open system with an influent stream of reactants and an effluent stream of products.[2]:41 A lake can be regarded as a tank reactor, and lakes with long turnover times (e.g. with low flux-to-volume ratios) can for many purposes be regarded as continuously stirred (e.g. homogeneous in all respects). The mass balance then becomes

where Q0 and Q denote the volumetric flow in and out of the system respectively and CA,0 and CA the concentration of A in the inflow and outflow respective. In an open system we can never reach a chemical equilibrium. We can, however, reach a steady state where all state variables (temperature, concentrations etc.) remain constant ( ).

).

Example

Consider a bathtub in which there is some bathing salt dissolved. We now fill in more water, keeping the bottom plug in. What happens?

Since there is no reaction,  and since there is no outflow

and since there is no outflow  . The mass balance becomes

. The mass balance becomes

or

Using a mass balance for total volume, however, it is evident that  and that

and that  . Thus we get

. Thus we get

Note that there is no reaction and hence no reaction rate or rate law involved, and yet  . We can thus draw the conclusion that reaction rate can not be defined in a general manner using

. We can thus draw the conclusion that reaction rate can not be defined in a general manner using  . One must first write down a mass balance before a link between

. One must first write down a mass balance before a link between  and the reaction rate can be found. Many textbooks, however, define reaction rate as

and the reaction rate can be found. Many textbooks, however, define reaction rate as

without mentioning that this definition implicitly assumes that the system is closed, has a constant volume and that there is only one reaction.

Ideal plug flow reactor (PFR)

The idealized plug flow reactor is an open system resembling a tube with no mixing in the direction of flow but perfect mixing perpendicular to the direction of flow. Often used for systems like rivers and water pipes if the flow is turbulent. When a mass balance is made for a tube, one first considers an infinitesimal part of the tube and make a mass balance over that using the ideal tank reactor model.[2]:46–47 That mass balance is then integrated over the entire reactor volume to obtain:

In numeric solutions, e.g. when using computers, the ideal tube is often translated to a series of tank reactors, as it can be shown that a PFR is equivalent to an infinite number of stirred tanks in series, but the latter is often easier to analyze, especially at steady state.

More complex problems

In reality, reactors are often non-ideal, in which combinations of the reactor models above are used to describe the system. Not only chemical reaction rates, but also mass transfer rates may be important in the mathematical description of a system, especially in heterogeneous systems.[3]

As the chemical reaction rate depends on temperature it is often necessary to make both an energy balance (often a heat balance rather than a full fledged energy balance) as well as mass balances to fully describe the system. A different reactor model might be needed for the energy balance: A system that is closed with respect to mass might be open with respect to energy e.g. since heat may enter the system through conduction.

Commercial use

In industrial process plants, using the fact that the mass entering and leaving any portion of a process plant must balance, data validation and reconciliation algorithms may be employed to correct measured flows, provided that enough redundancy of flow measurements exist to permit statistical reconciliation and exclusion of detectably erroneous measurements. Since all real world measured values contain inherent error, the reconciled measurements provide a better basis than the measured values do for financial reporting, optimization, and regulatory reporting. Software packages exist to make this commercially feasible on a daily basis.

See also

- Bioreactor

- Chemical reactor

- Chemical engineering

- Chemical equilibrium

- Conservation of mass

- Continuity equation

- Continuous stirred-tank reactor

- Dilution (equation)

- Energy accounting

- Mass action

- Mass flux

- Material balance planning

- Data validation and reconciliation

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Himmelblau, David M. (1967). Basic Principles and Calculations in Chemical Engineering (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Weber, Walter J., Jr. (1972). Physicochemical Processes for Water Quality Control. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-92435-0.

- ↑ Perry, Robert H.; Chilton, Cecil H.; Kirkpatrick, Sidney D. (1963). Chemical Engineers' Handbook (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 4–21.

External links

- Material Balance Calculations

- Material Balance Fundamentals

- The Material Balance for Chemical Reactors

- Material and energy balance

- Heat and material balance method of process control for petrochemical plants and oil refineries, United States Patent 6751527

- Morris, Arthur E.; Geiger, Gordon; Fine, H. Alan (2011). Handbook on Material and Energy Balance Calculations in Material Processing (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-06565-5.