Martinique macaw

| Martinique macaw | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hypothetical 1907 restoration by John Gerrard Keulemans, based on Bouton's description | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Subfamily: | Psittacinae |

| Tribe: | Arini |

| Genus: | Ara |

| Species: | A. martinicus |

| Binomial name | |

| Ara martinicus (Rothschild, 1905) | |

| |

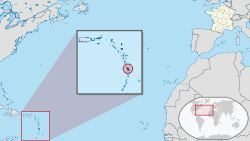

| Location of Martinique | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The Martinique macaw or orange-bellied macaw[1] (Ara martinicus) is an hypothetical extinct species of macaw which may have been endemic to the island of Martinique, an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was scientifically named by Walter Rothschild in 1905, based on a 1630s description of "blue and orange-yellow" macaws by Père Jacques Bouton. No other evidence of its existence is known, but it may have been identified in contemporary artwork. Some writers have suggested that the birds observed were actually blue-and-yellow macaws (Ara ararauna). The "red-tailed blue-and-yellow macaw" (Ara erythrura), another species described by Rothschild in 1907 based on a 1658 account, is thought to be identical to the Martinique macaw, if either has ever existed.

The Martinique macaw is one of thirteen extinct macaw species that have been proposed to have lived in the Caribbean islands. Many of these species are now considered dubious because only two are known from physical remains, and there are no extant endemic macaws on the islands today. Macaws were frequently transported between the Caribbean islands and the South American mainland in both prehistoric and historic times, so it is impossible to know whether contemporaneous reports refer to imported or native species.

Taxonomy

The Martinique macaw was scientifically described by Walter Rothschild in 1905, as a new species of the genus Anodorhynchus, A. martinicus. The taxon was solely based on a 1630s account by Père Jacques Bouton of blue and orange-yellow macaws from the Caribbean island of Martinique.[2] Rothschild reclassified the species as Ara martinicus in his 1907 book, Extinct Birds, which also contained a restoration of the bird by John Gerrard Keulemans.[3] The reassignment lead to confusion as recently as 2001, when Williams and Steadman assumed the two names were meant to refer to separate birds.[4] The Martinique amazon (Amazona martinicana) of the same island, was also based solely on a contemporary description.[5]

What Bouton described is likely to remain a mystery, but various theories havge been proposed.[6] In 1906, Tommaso Salvadori noted that the Martinique macaw seemed similar to the blue-and-yellow macaw (Ara ararauna) of mainland South America, and may had been the same bird.[7] James Greenway suggested Bouton's description could have been based on a captive bird. Edwards' Dodo, a 1626 painting by Roelant Savery, shows several birds including a blue and yellow macaw, which is different from the mainland bird in having yellow undertail covert feathers instead of blue, but the origin of this macaw is unknown.[8] Another Savery painting from about the same time shows a similar blue and yellow macaw, as does a mid-1700s illustration by Eleazar Albin.[9] In 1936, a Cuban scientist claimed to have found a stuffed Martinique macaw specimen, which was supposed to have been collected in 1845. After examination it was shown to be a hoax, combining a burrowing parakeet (Cyanoliseus patagonus byroni) with the tail of a dove.[4]

In the article that named the Martinique macaw, Rothschild also listed an "Anodorhynchus coeruleus", supposedly from Jamaica. Salvadori also questioned this in 1906, as he was unsure what Rothschild was referring to.[7] In his Extinct Birds, Rothschild clarified that his first description was erroneous, as he had misread an old description. He renamed it Ara erythrura, based on a 1658 description by Charles de Rochefort, and conceded that its provenance was unknown.[3] This supposed species subsequently received common names such as "red-tailed blue-and-yellow macaw" and "satin macaw" in the ornithological literature.[1][5] Greenway suggested Rochefort's description was dubious, as he had never visited Jamaica, and appeared to have based his account on one by Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre.[8] If either bird ever existed, Ara erythrura is likely to have been identical to the Martinique macaw.[1] Other similar blue and yellow macaws, such as the "great macaw" ("Psittacus maximus cyanocroceus") were also reported from Jamaica.[4]

Extinct Caribbean macaws

Macaws are known to have been transported between the Caribbean islands and from mainland South America both in historic times by Europeans and natives, and prehistoric times by Paleoamericans. Parrots were important in the culture of native Caribbeans, were traded between islands, and were among the gifts offered to Christopher Columbus when he reached the Bahamas in 1492. It is therefore difficult to determine whether the numerous historical records of macaws on these islands refer to distinct, endemic species, since they could have been based on escaped individuals or feral populations of foreign macaws of known species that had been transported there.[10] As many as thirteen extinct macaws have been suggested to have lived on the islands until recently.[11] Only two endemic Caribbean macaw species are known from physical remains; the Cuban macaw (Ara tricolor) is known from nineteen museum skins and subfossils, and the Saint Croix macaw (Ara autochthones), is only known from subfossils.[10] No endemic Caribbean macaws remain today; they were likely driven to extinction by humans in historic and prehistoric times.[5]

Many hypothetical extinct macaws were based only on contemporaneous accounts, but these species are considered dubious today. Several of them were named in the early 20th century by Rothschild, who had a tendency to name species based on little tangible evidence.[6] Among others, the Lesser Antillean macaw (Ara guadeloupensis) and the violet macaw (Anodorhynchus purpurascens) were based on reports of macaws on Guadeloupe, the red-headed macaw (Ara erythrocephala) and the Jamaican red macaw (Ara gossei) were named for accounts of macaws on Jamaica, and the Dominican green-and-yellow macaw (Ara atwoodi) was supposedly from Dominica island.[3]

Other species of macaw have also been mentioned, but many never received binomials, or are considered junior synonyms of other species.[1] Williams and Steadman defended the validity of most named Caribbean macaw species, and wrote that each Greater and Lesser Antillean island had its own endemic species.[5] Olson and Maíz doubted the validity of the hypothetical macaws, and that all Antillean islands once had endemic species, but wrote that the island of Hispaniola would be the most likely place for another macaw species to have existed because of the large land area, though no descriptions or remains of such are known. They wrote that such a species could have been driven to extinction before the arrival of Europeans.[10] The prehistoric distribution of indigenous macaws in the Caribbean can only be determined through further palaeontological discoveries.[12]

Contemporary descriptions

Bouton's original description of the Martinique macaw is reproduced below, translated from French:

The macaws are two or three times as large as the other parrots, [and] have a plumage much different in colour: those that I have seen have their plumage blue and orange-yellow (saffron). They also learn to talk and have a good body.[3][9]

A translation of the original French description of "Ara erythrura" by de Rochefort follows below:

Among them are some which have the head, the upper side of the neck, and the back of a satiny sky blue; the underside of the neck, the belly, and undersurface of the wings, yellow, and the tail entirely red.[3]

In spite of the fact that the tail of "Ara erythrura" was described as entirely red, the plate in Rothschild's Extinct Birds showed a blue tip, which Charles Wallace Richmond complained about in his review of the book.[13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. A & C Black. p. 399. ISBN 1-4081-5725-X.

- ↑ Rothschild, W. (1905). "Notes on extinct parrots from the West Indies". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 16: 13–15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Rothschild, W. (1907). Extinct Birds. London: Hutchinson & Co. pp. 53–54.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Wiley, J. W.; Kirwan, G. M. (2013). "The extinct macaws of the West Indies, with special reference to Cuban Macaw Ara tricolor". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 133: 125–156.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Williams, M. I.; D. W. Steadman (2001). "The historic and prehistoric distribution of parrots (Psittacidae) in the West Indies". In Woods, C. A. and Sergile, F. E. (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives (pdf) (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 175–189. ISBN 0-8493-2001-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fuller, E. (1987). Extinct Birds. Penguin Books (England). pp. 233–236. ISBN 0-670-81787-2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Salvadori, T. (1906). "Notes on the parrots (Part V.)". Ibis 48 (3): 451–465. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1906.tb07813.x.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Greenway, J. C. (1967). Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World. American Committee for International Wild Life Protection. pp. 314–319. ISBN 0-486-21869-4.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Species Info: Ara martinica". The Extinction Website (2008). Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Olson, S. L.; Maíz López, E. J. (2008). "New evidence of Ara autochthones from an archaeological site in Puerto Rico: a valid species of West Indian macaw of unknown geographical origin (Aves: Psittacidae)" (pdf). Caribbean Journal of Science 44 (2): 215–222.

- ↑ Turvey, S. T. (2010). "A new historical record of macaws on Jamaica". Archives of Natural History 37 (2): 348–351. doi:10.3366/anh.2010.0016.

- ↑ Olson, S. L.; Suárez, W. (2008). "A fossil cranium of the Cuban Macaw Ara tricolor (Aves: Psittacidae) from Villa Clara Province, Cuba". Caribbean Journal of Science. 3 44: 287–290.

- ↑ Richmond, C. W. (1908). "Recent literature: Rothschild's 'Extinct Birds'". The Auk 25 (2): 238–240. doi:10.2307/4070727. JSTOR 4070727.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||