Marsy's Law

| Marsy's Law (Proposition 9) California Victims' Bill of Rights | |

| Definition: | Crime Victims Bill of Rights |

| State: | California |

| Passed: | November 4, 2008 |

| Key people: | Henry T Nicholas, III, Todd Spitzer, Steve Ipsen |

| Namesake: | Marsalee Nicholas, murdered 11-30-1983 |

| Website: | Marsy's Law, California Office of the Attorney General Marsy's Law For All homepage Ballotpedia page |

Marsy's Law, the California Victims' Bill of Rights Act of 2008, is an Amendment to the state's Constitution and certain Penal Code sections enacted by voters through the initiative process in the November 2008 general election. The Act protects and expands the legal rights of victims of crime to include 17 rights in the judicial process, including the right to legal standing, protection from the defendant, notification of all court proceedings, and restitution, as well as granting parole boards far greater powers to deny inmates parole.[1]

Background

Marsy Nicholas was the sister of Henry Nicholas, the Co-Founder and former Co-Chairman of the Board, President and Chief Executive Officer of Broadcom Corporation. In 1983, Marsy, then a senior at UC Santa Barbara, was stalked and murdered by her ex-boyfriend. Her murderer, Kerry Conley, was tried by a Los Angeles jury and sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole. Although he died in prison one year before Marsy's Law passed, the Nicholas family attended numerous parole hearings, which haunted them for years.[2]

Nicholas was the main organizer and sponsor of the campaign to pass Marsy's Law, whom former California Governor Pete Wilson called the "driving force" behind the constitutional amendment.[3] In late 2007, Nicholas convened a group, including Wilson, to consider putting a comprehensive victims' rights constitutional amendment on the ballot in California. The effort grew out of frustration that, despite previous legislative measures, victims still lacked adequate protection in the judicial system. Nicholas recruited noted legal scholars and former prosecutors to draft, rework and write the final version of the bill. In addition to Nicholas and Wilson, contributors included:

- Steve Twist, noted victims' rights legal expert and author of Arizona's Victims' Bill of Rights

- Douglas Pipes, recognized legal scholar

- Douglas Beloof, professor at the Lewis & Clark Law School and board member of the National Crime Victims' Law Institute (NCVLI)

- Meg Garvin, Executive Director of the NCVLI

- Steve Ipsen, Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney and then-President of the Los Angeles Association of Deputy District Attorneys

- Todd Spitzer, then-State Assemblyman, former Orange County Assistant District Attorney and Marsy's Law Legal Affairs Director

- Paul G. Cassell, former federal judge, University of Utah law professor

- Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation

- Thomas Hiltachk, then-legal counsel to then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger

- Charles Fennessey, senior policy consultant to then-State Senator George Runner[4]

Co-signatories of the Constitutional Amendment included Henry Nicholas; his mother, Marcella Leach, a long-time victims' rights advocate and leader of Justice for Homicide Victims; and, LaWanda Hawkins, founder of Justice for Murdered Children. Todd Spitzer served as chair for the Marsy's Law campaign. Voters passed the Constitutional Amendment by a margin of 53.84% to 46.16%, despite being opposed by nearly every major newspaper in the state.[4]

In 2009, Henry Nicholas formed Marsy's Law for All,[5] which has the following objectives:

- Ensure that Marsy's Law is enforced throughout California;

- Help crime victims obtain quality legal representation;

- Unite the victims' rights movement by providing organizations with media, technology and other support;

- Pass an Amendment to the United States Constitution to protect the rights of victims nationwide

Impact of Marsy's Law

Since its passage, Marsy's Law has had a major impact on how victims are treated in the state's judicial system. Now, when any victim of crime is contacted by law enforcement, just as the accused are read their Miranda Rights, that victim is immediately informed of his or her Marsy's Rights and provided with "Marsy's Card" a small foldout containing a full description of each of the 17 Marsy's Rights, which is also available for download in 17 languages on the California Office of the Attorney General website.[6] The California Attorney General has published these rights, which now are utilized by every law enforcement agency in the state. In addition, each of 58 county District Attorney's offices are required to inform victims of these rights at the time a case is filed for criminal prosecution.[7] In 2010, the California Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) amended its Learning Domain 04 to include Marsy’s Law Training it is Basic Police Academy.[8]

In January 2010, the University of California, Irvine School of Law and Dean Erwin Chemerinsky partnered with Marsy's Law for All and the National Crime Victim Law Institute to host the first Marsy's Rights attorney training. More than 100 lawyers learned about the provisions of Marsy's Law and how to represent victims in criminal matters.[9]

Victims now have the right to be heard at every stage of the legal criminal proceedings, which means before the judge makes a sentencing offer in the case. Prior to the passage of Proposition 9, most victims did not address the court until after a conviction or plea. In addition, actions to bar victims from the courtroom under a "motion to exclude witnesses" are now routinely denied. Victims have a right to be present in court and prosecutors are trained to call victims who will be witnesses in the case to testify first so they can remain in the courtroom for the entire trial.

Marsy's Law also gives victims the right to be represented by counsel of their choosing, rather than relying on the prosecutor, who has a legal obligation to represent the people of his or her jurisdiction, and not the victim. Marsy's Law rights are enforceable and an adverse ruling against a victim in any context involving these rights can be appealed to a higher court by victims through their own counsel or the District Attorney.

Post-conviction, victims' rights have been impacted by the dramatic increase in the length of time between parole hearings. Before Marsy's Law, the maximum parole denial was five years for convicted murderers and two years for all other crimes. Marsy Nicholas' mother, Marcella Leach, suffered a heart attack at the second parole hearing for Marsy's killer and was unable to attend subsequent hearing for many years.[10] Now parole denials can be imposed for 7, 10 and even 15 years. Statistics show that in 2009, 20% or 656 inmates received parole denials of 7 years or more. In 2009, only 3.5% received denials of two years or less.[9]

Citing the impact of Marsy's Law in extending the time California prison inmates must wait between hearings after parole has been denied, a Stanford University study of 32,000 California prisoners serving life sentences with the possibility of parole found the likelihood of parole for a convicted murderer is 6%. The study also found that the lifer population has increased from 8% of inmates in 1990 to 20% in 2010 and that the average number of years served is 20.[11]

In another study on the impact of Marsy's Law on the parole process, UCLA law student Laura L. Richardson found a doubling in the average length of time imposed between parole hearings since California voters passed the Constitutional Amendment in 2008. But while victims may impact parole decisions, her analysis of 211 parole hearings failed to reveal an increase in victim participation in the parole process.[12]

The California Supreme Court has said it will review two cases, In re Vicks and In re Russo, which address whether the parole impact of Marsy's Law is unconstitutional. In Vicks, the state Court of Appeal, Fourth Appellate District, Division One found that the risk of increased incarceration resulting from longer parole denials under Marsy's Law violated ex post facto principles if applied to prisoners sentenced before the law was passed. However, in Russo, a different panel from the same court ruled that the ability of a prisoner who had been denied parole to petition to advance the date of the next parole hearing protected Marsy’s Law from an ex post facto challenge.[13]

Key cases involving Marsy's Law

- San Diego District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis, arguing violations of the notification provisions in Marsy’s Law, sued to nullify former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s decision on his last day in office to cut the sentence of the son of the former Assembly Speaker Fabian Nunez. Estaban Nunez pleaded guilty in the 2008 fatal stabbing of Luis Santos in San Diego.[14] As a result of Schwarzenegger's action in the Nunez case, the California Assembly unanimously passed AB 684, which requires the governor to give at least 10 days notice before granting clemency to a convicted criminal.[15]

- The California Assembly defeated SB9, a bill that would have given juvenile offenders serving life sentences without parole the opportunity for release. Critics charged the bill violated victims’ rights of judicial finality guaranteed under Marsy’s Law.[16]

- A legal challenge under Marsy's Law to force the San Mateo District Attorney to reinstate criminal charges for misrepresenting as a lack of victim cooperation the reason for plea-bargaining a child molestation case.[17]

- The San Joaquin County District Attorney's Office reversed its position of lifting a gag order after the family of murder victim Sandra Cantu formally objected under Marsy's Law.[18]

- In Orange County, Nick Adenhart, a major league baseball pitcher for the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, was killed by a drunken driver in 2010 along with his passengers Henry Pearson and Courtney Stewart. Another passenger, Jon Wilhite, was critically injured. The victims retained counsel through Michael Fell, a California attorney who concentrates on victims' rights and Marsy's Law. Fell successfully argued against defense motions to continue the case, change venue to a different county, and allow cameras in the courtroom. It was the first time in Orange County that Marsy's Law was utilized in a jury trial. Andrew Gallo was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 51 years to life in prison.[19]

- In 2010 in San Diego, 17-year-old Chelsea King was raped and strangled. John Gardner, a paroled sex offender, pleaded guilty to killing King and 14-year-old Amber Dubois a year earlier. Gardner was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility parole. The King family retained attorney Mr. Fell along with a San Diego law firm to enforce their Marsy's Law rights and to ensure that sensitive crime scene and autopsy photos of their daughter were not released to the media. Through Fell’s work with the King family, no such photos were released to the public.[20]

- In December 2010, Lynette Duncan retained an attorney under Marsy's Law to accompany her to the parole hearing for Brett Thomas, who shot and killed her father and sister 33 years ago in Anaheim, CA. Thomas, along with another teenager, Mark Titch, went on a nine-day crime spree in January 1977, killing four people, including Aubry and Denise Duncan in an attempted robbery outside the Duncan family's home. Lynett's mother was critically injured in the attack and eventually recovered, but the family was emotionally destroyed by the crime.[21] Thomas and Titch pleaded guilty to multiple murder counts. They were sentenced to life in prison but eligible for parole after seven years. They repeatedly had been denied parole and this was the first time a member of the Duncan family appeared to argue against the murderers' release. Thomas postponed the hearing at the last minute, but Lynette Duncan delivered a statement arguing that Thomas' parole bid be rejected for the maximum 15 years under Marsy's Law. According to the Orange county Register, in her statement, "Duncan said she had lived in fear for 33 years, since the tragedy at her parents' home when she was 17, especially when she hears -- and remembers -- the sound of police and ambulance sirens." The Orange County Register reported that Duncan's attorney, Michael Fell, told the Parole Commissioners that Thomas was afraid to face Duncan. "After 33 years, my client mustered the courage to face [Thomas]," Fell said. "Inmate Thomas, however, can't find the courage to face her."[21]

- In October 2011, victims' rights advocates Jack and Genelle Reilly succeeded in their efforts to obtain the extradition from Illinois of former Marine and convicted serial killer Andrew Urdiales, also accused of murdering their daughter, Robbin Brandley, in Orange County, California in 1986. The Reilleys argued their right to extradition under Marsy's Law.[22] This is the first serial murder case in California to involve Marsy's Law.

Overview of the Constitutional Amendment

Marsy's Law amended the state constitution and various state laws to (1) expand the legal rights of crime victims and the payment of restitution by criminal offenders, (2) restrict the early release of inmates, and (3) change the procedures for granting and revoking parole. These changes are discussed in more detail below.[23]

Expansion of the rights of victims and restitution

Background

In June 1982, California voters approved Proposition 8, known as the Victims Bill of Rights.[24]

Among other changes, the proposition amended the Constitution and various state laws to grant crime victims the right to be notified of, to attend, and to state their views at, sentencing and parole hearings. Other separately enacted laws have created other rights for crime victims, including the opportunity for a victim to obtain a judicial order of protection from harassment by a criminal defendant.

Proposition 8 established the right of crime victims to obtain restitution from any person who committed the crime that caused them to suffer a loss. Restitution often involves replacement of stolen or damaged property or reimbursement of costs that the victim incurred as a result of the crime. A court is required under current state law to order full restitution unless it finds compelling and extraordinary reasons not to do so.[24]

Sometimes, however, judges do not order restitution. Proposition 8 also established a right to "safe, secure and peaceful" schools for students and staff of primary, elementary, junior high, and senior high schools.

Changes made by this measure

Restitution. This measure requires that, without exception, restitution be ordered from offenders who have been convicted, in every case in which a victim suffers a loss. The measure also requires that any funds collected by a court or law enforcement agencies from a person ordered to pay restitution would go to pay that restitution first, in effect prioritizing those payments over other fines and obligations an offender may legally owe. The victim also is entitled to be compensated for legal fees in hiring counsel under Marsy’s Law on the issues relating to the securing of restitution.[25]

Notification and participation of victims in criminal justice proceedings

As noted above, Proposition 8 established a legal right for crime victims to be notified of, to attend, and to state their views at, sentencing and parole hearings. This measure expands these legal rights to include all public criminal proceedings, including the release from custody of offenders after their arrest, but before trial. In addition, victims are given the constitutional right to participate in other aspects of the criminal justice process, such as conferring with prosecutors on the charges filed and arguing for increased charges. Also, law enforcement and criminal prosecution agencies are required to provide victims with specified information, including details on victim's rights.[26]

Other expansions of victims' legal rights

This measure expands the legal rights of crime victims in various other ways, including the following:

- Crime victims and their families have a state constitutional right to (1) prevent the release of their confidential information or records to criminal defendants, (2) refuse to be interviewed or provide pretrial testimony or other evidence requested in behalf of a criminal defendant, (3) protection from harm from individuals accused of committing crimes against them, which includes informing the judge of safety concerns and seeking protective orders, (4) the return of property no longer needed as evidence in criminal proceedings, and (5) ‚"finality" in criminal proceedings in which they are involved and the right to due process and a speedy trial. Some of these rights previously existed in statute.[1]

- The Constitution was changed to specify that the safety of a crime victim must be taken into consideration by judges in setting bail for persons arrested for crimes.

- The measure states that the right to safe schools includes community colleges, colleges, and universities.[1]

Restrictions on early release of inmates

Background

The state operates 33 state prisons and other facilities that had a combined adult inmate population of about 171,000 as of May 2008. The costs to operate the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) in 2008 are estimated to be approximately $10 billion. The average annual cost to incarcerate an inmate is estimated to be about $46,000. The state prison system is currently experiencing overcrowding because there are not enough permanent beds available for all inmates. As a result, gymnasiums and other rooms in state prisons have been converted to house some inmates.

Both the state Legislature and the courts have been considering various proposals that would reduce overcrowding, including the early release of inmates from state prison. At the time this analysis was prepared, none of these proposals had been adopted. State prison populations are also affected by credits granted to prisoners. These credits, which can be awarded for good behavior or participation in specific programs, reduce the amount of time a prisoner must serve before release.[27] Collectively, the state's 58 counties spend over $2.4 billion on county jails, which have a population in excess of 80,000. There are currently 20 counties where an inmate population cap has been imposed by the federal courts and an additional 12 counties with a self-imposed population cap. In counties with such population caps, inmates are sometimes released early to comply with the limit imposed by the cap. However, some sheriffs also use alternative methods of reducing jail populations, such as confining inmates to home detention with Global Positioning System (GPS) devices.[28]

Changes made

This measure amends the Constitution to require that criminal sentences imposed by the courts be carried out in compliance with the courts' sentencing orders and that such sentences shall not be "substantially diminished" by early release policies to alleviate overcrowding in prison or jail facilities. The measure directs that sufficient funding be provided by the Legislature or county boards of supervisors to house inmates for the full terms of their sentences, except for statutorily authorized credits which reduce those sentences.

Changes affecting the granting and revocation of parole

Background

The Board of Parole Hearings conducts two different types of proceedings relating to parole. First, before CDCR releases an individual who has been sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole, the inmate must go before the board for a parole consideration hearing. Second, the board has authority to return to state prison for up to a year an individual who has been released on parole but who subsequently commits a parole violation. (Such a process is referred to as parole revocation.) A federal court order requires the state to provide legal counsel to parolees, including assistance at hearings related to parole revocation charges.[29]

Changes made

Parole Consideration Procedures for Lifers. This measure changes the procedures to be followed by the board when it considers the release from prison of inmates with a life sentence. Specifically:

- Previously, individuals whom the board did not release following their parole consideration hearing generally waited between one and five years for another parole consideration hearing. This measure extends the time before the next hearing to between 3 and 15 years, as determined by the board. However, inmates are able to periodically request that the board advance the hearing date.

- Crime victims are eligible to receive earlier notification in advance of parole consideration hearings. They receive 90 days advance notice, instead of the current 30 days.

- Previously, victims were able to attend and testify at parole consideration hearings with either their next of kin and up to two members of their immediate family, or two representatives. The measure removes the limit on the number of family members who could attend and testify at the hearing, and allows victim representatives to attend and testify at the hearing without regard to whether members of the victim's family were present.

- Those in attendance at parole consideration hearings are eligible to receive a transcript of the proceedings. This allows the victim to document the level of remorse and rehabilitation exhibited by the inmate in order to make the parole board aware at subsequent hearings if the inmates' behavior fails to demonstrate remorse or other failure to take personal responsibility for his crime.

- General Parole Revocation Procedures. This measure changes the board's parole revocation procedures for offenders after they have been paroled from prison. Under a federal court order in a case known as Valdivia v. Schwarzenegger, parolees were entitled to a hearing within 10 business days after being charged with violation of their parole to determine if there is probable cause to detain them until their revocation charges are resolved. The measure extends the deadline for this hearing to 15 days. The same court order also required that parolees arrested for parole violations have a hearing to resolve the revocation charges within 35 days. This measure extends this timeline to 45 days. The measure also provides for the appointment of legal counsel to parolees facing revocation charges only if the board determines, on a case-by-case basis, that the parolee is indigent because of the complexity of the matter or because of the parolee's mental or educational incapacity, the parolee appears incapable of speaking effectively in his or her defense. Because this measure does not provide for counsel at all parole revocation hearings, and because the measure does not provide counsel for parolees who are not indigent, a federal judge held it was in conflict with the Valdivia court order, which requires that all parolees be provided legal counsel. However, in March 2010, the Federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the lower court ruling and directed it to reconcile its ruling with Proposition 9.[30]

Newspaper endorsements

Editorial boards opposed

The Los Angeles Times encouraged a "no" vote on 9, saying, "If the concern is protection of families from further victimization, as proponents claim, that goal can be met without granting families a new and inappropriate role in prosecutions."[31]

Other editorial boards opposed:

|

Editorial boards in favor

- The Eureka Reporter.[59]

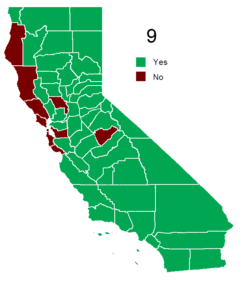

Results

| Proposition 9[60] | ||

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| |

6,682,465 | 53.84 |

| No | 5,728,968 | 46.16 |

| Valid votes | 12,411,433 | 90.31 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 1,331,744 | 9.69 |

| Total votes | 13,743,177 | 100.00 |

See also

- The Henry T. Nicholas, III Foundation

- Henry Nicholas

- Todd Spitzer

- Michael Fell

- Bob Leach

- Marcella Leach

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/content/bill_of_rights.php

- ↑ http://articles.ocregister.com/2010-04-20/crime/24635277_1_henry-nicholas-murder-victim-marsy-s-law

- ↑ http://www.ocregister.com/articles/nicholas-245053-marsy-victims.html

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/marsys_law.php

- ↑ http://marsyslawforall.org

- ↑ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/marsy.php

- ↑ http://oag.ca.gov/victims

- ↑ http://post.ca.gov/regular-basic-course-training-specifications.aspx

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 http://www.euroinvestor.co.uk/news/story.aspx?id=11018785&bw=20100426005708

- ↑ http://www.oclnn.com/orange-county/2010-04-20/courts-crime/victims-rights-supporters-march-to-remember-lost-friends-family

- ↑ http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/stanford-criminal-justice-center-issues-first-major-study-of-california-prisoners-serving-life-sentences-with-possibility-of-parole-129882663.html

- ↑ http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1878594

- ↑ http://uscpcjp.com/?p=445

- ↑ http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/2011/may/11/dumanis-sues-nullify-commutation-nunezs-sentence/

- ↑ The San Francisco Chronicle http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2011/08/29/state/n130902D43.DTL&type=politics. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Lagos, Marisa (August 26, 2011). "Bill to give juvenile lifers a second chance fails". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ http://www.smdailyjournal.com/article_preview.php?id=138152&title=Victim%20group:%20Reinstate%20molestation%20case

- ↑ http://www.news10.net/news/article.aspx?storyid=82058&provider=top&catid=188

- ↑ http://www.ocregister.com/articles/gallo-281330-adenhart-driving.html

- ↑ http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/2010/apr/22/gag-order-gardner-case-stays-place-now/ http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/2010/apr/20/chelseas-family-seeks-keep-case-files-private/

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 http://www.ocregister.com/news/parole-281901-thomas-duncan-html

- ↑ http://www.ocregister.com/news/peterson-279871-orange-relationship.html

- ↑ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/content/statement.php

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 The Star (Toronto) http://www3.thestar.com/static/PDF/crime/Doob_Zimring_California.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.alcoda.org/victim_witness/marsys_law

- ↑ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/notification.php

- ↑ Lagos, Marisa (February 18, 2010). "Rapist Moved From School Area / Residents picketed boarding house". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ http://nicic.gov/features/statestats/?state=ca

- ↑ "Marsy's Law: Crime Victims' Bill of Rights Act of 2008 Campaign Announcement". Business Wire. April 16, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.cjlf.org/releases/10-10.htm

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, "No on Proposition 9", September 26, 2008

- ↑ Pasadena Star News, "Vote 'no' on props. 6 and 9", October 6, 2008

- ↑ Press Democrat, "Wrong Way," September 8, 2008

- ↑ Press Enterprise, "No on 9," September 12, 2008

- ↑ Tracy Press, "Proposition 9 has victims as a concern, but it would put too much burden on our prison system if it passes," September 23, 2008.

- ↑ San Diego Union Tribune, "No on Prop 9: Measure is poorly drafted and wrongheaded," September 25, 2008

- ↑ Orange County Register, "California Prop. 9 Editorial: Unnecessary tinkering with constitution," October 2, 2008

- ↑ Sacramento Bee, "Proposition 9", October 9, 2008

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle, "Props. 6 and 9 are budget busters," October 9, 2008.

- ↑ Bakersfield Californian, "Ballot-box budgeting: Vote NO on Props 6 and 9," October 9, 2008

- ↑ La Opinion, "Two Measures to Reject," October 12, 2008

- ↑ Fresno Bee, "Vote 'no' on Proposition 9, an ill-considered crime victims bill," October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Woodland Daily Democrat, "Voters should turn down Props. 5, 6, and 9", October 14, 2008.

- ↑ San Jose Mercury News, "Editorial: Proposition 9 would increase prison costs; vote no," October 14, 2008.

- ↑ Chico Enterprise-Record, "Flawed measures should be rejected," October 16, 2008.

- ↑ Stockton Record, "Proposition 9 ‚Äö√Ñ√¨ No," October 16, 2008.

- ↑ New York Times, "Fiscal Disaster in California," October 9, 2008.

- ↑ Contra Costa Times, "Times recommendations on California propositions," October 19, 2008.

- ↑ San Gabriel Valley Tribune, "Propositions in Review," October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Napa Valley Register, Vote No On Proposition 9, October 16, 2008

- ↑ Salinas Californian, "Vote no on state Props. 5, 6 and 9," October 18, 2008.

- ↑ Monterey County Herald, "Proposition endorsements," October 17, 2008.

- ↑ Long Beach Press-Telegram, "No on Proposition 9," October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Desert Dispatch, "Victims' Rights Yes, Amendment No," October 8, 2008

- ↑ The Reporter, "Vote No on Prop. 9," October 22, 2008.

- ↑ Los Angeles Daily News, "No on Props. 5, 6, and 9.

- ↑ Santa Cruz Sentinel, "As We See It: Vote No on Props. 6 and 9," October 15, 2008.

- ↑ Modesto Bee, "Prop. 9 is too ambitious," October 9 2008.

- ↑ Eureka Reporter, "The Eureka Reporter recommends," October 14, 2008

- ↑ "Statement of Vote: 2008 General Election" (PDF). California Secretary of State. December 13, 2008.

External links

- California Office of the Attorney General, Marsy's Law

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), Victim's Bill of Rights Act of 2008: Marsy's Law

- Marsy's Law For All, official website

- Henry T. Nicholas, III Foundation

- Ballotpedia, Proposition 9

- Full text of Proposition 9

- Campaign Expenditures for Marsy's Law

| ||||||||||||||||||||||