Marooned (film)

| Marooned | |

|---|---|

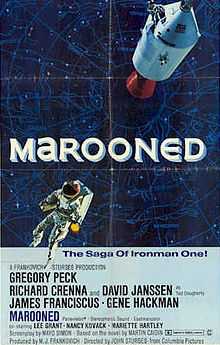

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Sturges |

| Produced by | M. J. Frankovich |

| Screenplay by | Mayo Simon |

| Based on |

Marooned (novel) by Martin Caidin |

| Starring |

Gregory Peck Richard Crenna David Janssen James Franciscus Gene Hackman |

| Cinematography | Daniel L. Fapp |

| Edited by | Walter Thompson |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 134 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8-10 million[1] |

| Box office | $4.1 million (USA / Canada rentals)[1][2] |

Marooned is a 1969 Eastmancolor American film directed by John Sturges and starring Gregory Peck, Richard Crenna, David Janssen, James Franciscus, and Gene Hackman.[3] It was based on the 1964 novel Marooned by Martin Caidin. While the original novel was based on the single-pilot Mercury program, the film depicted an Apollo Command/Service Module with three astronauts and a space station resembling Skylab. Caidin acted as technical adviser and updated the novel, incorporating appropriate material from the original version.

The film was released less than four months after the Apollo 11 moon landing and was tied to the public fascination with the event. It won an Academy Award for Visual Effects for Robbie Robertson.

Plot

Three American astronauts – commander Jim Pruett (Richard Crenna), "Buzz" Lloyd (Gene Hackman), and Clayton "Stoney" Stone (James Franciscus) – are the first crew of an experimental space station on an extended duration mission. While returning to Earth, the main engine on the Apollo spacecraft Ironman One fails. Mission Control determines that Ironman does not have enough backup thruster capability to initiate atmospheric reentry, or to re-dock with the station and wait for rescue. The crew is marooned in orbit.

NASA debates whether a rescue flight can reach the crew before their oxygen runs out in approximately two days. There are no backup launch vehicles or rescue systems available at Kennedy Space Center and NASA director Charles Keith (Peck) opposes using an experimental Air Force X-RV lifting body that would be launched on a Titan IIIC booster; neither the spacecraft nor the booster is man-rated, and there is insufficient time to put a new manned NASA mission together. Even though a booster is already on the way to nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force Station for an already-scheduled Air Force launch, many hundreds of hours of preparation, assembly, and testing would be necessary.

Ted Dougherty (David Janssen), the Chief Astronaut, opposes Keith and demands that something be done. The president agrees with Dougherty and tells Keith that failing to try a rescue mission will kill public support for the manned space program. The President tells Keith that money is no factor; "whatever you need, you've got it".

While the astronauts' wives (Lee Grant, Mariette Hartley, and Nancy Kovack) agonize over the fates of their husbands, all normal checklist procedures are bypassed to prepare the X-RV for launch. A hurricane headed for the launch area threatens to cancel the mission, scrubbing the final attempt to launch in time to save all three Ironman astronauts. However, the eye of the storm passes over the Cape 90 minutes later during a launch window, permitting a launch with Dougherty aboard in time to reach the ship while at least some of the crew survives.

Insufficient oxygen remains for all three astronauts to survive until Dougherty arrives. There is possibly enough for two. Pruett and his crew then debate what to do. Stone tries to reason that they can somehow survive by taking sleeping pills or otherwise reducing oxygen consumption. Lloyd offers to leave since he is "using up most of the oxygen anyway", but Pruett overrules him. He orders everyone into their spacesuits then leaves the ship, ostensibly to attempt repairs (although this option has been repeatedly dismissed as impractical).

When Lloyd sees Pruett going out the hatch, he attempts to follow. Before he can reach him, Pruett's space suit has been torn on a metal protrusion and oxygen rapidly escapes, leading to Pruett's death by anoxia. (It is not made explicit in the movie whether Pruett's death is intentional or not. While he had discussed the oxygen supply issue with the other astronauts, he shows clear alarm and shock when he sees the tear in his suit.) Lloyd looks on as Pruett's body drifts away into space. With Pruett gone, Stone takes command.

A Soviet spacecraft suddenly appears and its cosmonaut tries to make contact. It can do nothing but deliver oxygen since the Soviet ship is too small to carry additional passengers. Stone and Lloyd, suffering oxygen deprivation, cannot understand the cosmonaut's gestures or obey Keith's orders.

Dougherty arrives and he and the cosmonaut transfer the two surviving and mentally dazed Ironman astronauts into the rescue ship. Both the Soviet ship and the X-RV return to Earth, and the final scene fades out with a view of the abandoned Ironman One adrift in orbit.

Cast

|

|

Cast notes:

- Martin Caidin, the author of the book the movie was based on, and a technical advisor for the film, makes a brief appearance in the film as a reporter describing the arrival of the X-RV at Cape Canaveral.

Production

Given that Apollo missions were being watched regularly by television audiences, it was very important to the producers that the look of the film be as authentic as possible. NASA, and its primary contractors such as North American Aviation and Philco-Ford, helped with the design of the film's hardware, including the crew's chairs inside the capsule, the orbiting laboratory - which used an early mock-up of the Skylab concept, the service module,[4] the actual Plantronics headsets worn by the actors in the spacecraft, as well as authentic replicas of actual facilities such as the Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR) at Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Air Force Launch Control Center (AFLCC) at Cape Canaveral AFS. Contractors' technicians also worked on the film.

The Apollo Command Module used in making the film was an actual "boilerplate" version of the "Block I" Apollo spacecraft; no Block I ever flew with a crew aboard. While the Block II series had a means of rapidly blowing the hatch open, the Block I did not, and the interior set was constructed using the boilerplate as a model. To blow the hatch in the movie, Buzz pulls on a handle attached to a hinge.

Astronaut Jim Lovell and his wife Marilyn Lovell referred to the film years later in a special interview. Their recollection is shared as a feature on the DVD release of Apollo 13, a 1995 film directed by Ron Howard. The couple describes a 1969 film – never specifically named – in which an astronaut in an Apollo spacecraft "named Jim" faces mortal peril. The couple says the film gave Lovell's wife nightmares. Her experience inspired a dream sequence in Apollo 13.

There were some discrepancies between real-life procedures and what is shown in the film. For instance, several scenes show various people communicating directly with the astronauts in space. In actuality, only CAPCOM (an astronaut) and astronauts' wives would have been permitted to communicate with the spacecraft, all others in MOCR and AFLCC would only be able to communicate on the internal network or to their respective backroom teams.[5] Conspicuously absent from the film is any person resembling a flight director. In real life, "Flight" is in charge of a space mission during that director's shift. The filmmakers felt that adding a flight director would distract from the interpersonal dynamic between Keith and Dougherty.

Legacy

During the preliminary discussions for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project the film was discussed as a means of alleviating Soviet suspicion.[6] One purpose of the mission was to develop and test capabilities for international space rescue.

In popular culture

- The 1970 Mad magazine satire of Marooned, called Moroned, described story events in actual film time. NASA officials are pressed to launch the X-RT — "the Experimental Rescue Thing" — in "about an hour…maybe, tops, an hour and a half". One astronaut sacrifices his life to escape the film critics.

- In 1991, Marooned was redistributed under the name Space Travelers by Film Ventures International, an ultra-low-budget production company that prepared quickie television and video releases of films that were in the public domain or could be purchased inexpensively. As Space Travelers, Marooned was mocked on a 1992 episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, becoming the only Academy Award winning film ever to receive the MST3K treatment.

- The second launch sequence served as the speech base for the comm chatter in the Disney rollercoaster Space Mountain.

- Alfonso Cuarón, director of 2013's Gravity, told Wired magazine, "I watched the Gregory Peck movie Marooned over and over as a kid."[7]

See also

- Apollo 13, a 1995 film dramatizing the Apollo 13 incident

- Gravity, a 2013 3D science-fiction space drama film

- List of films featuring space stations

- Love, a 2011 film about being stranded in space

- Survival film, about the film genre, with a list of related films

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lovell, Glenn. Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges, Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008, p 268-273

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1970", Variety (January 6, 1971), p 11

- ↑ Thompson, Howard. "Marooned (1969)" New York Times (December 16, 1969)

- ↑ Mateas, Lisa. "Marooned (1969)" (article) TCM.com

- ↑ Arstechnica.com

- ↑ Edward Clinton Ezell & Linda Neuman Ezell, The Partnership: A History of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project

- ↑ Roper, Caitlin. "Why Gravity Director Alfonso Cuarón Will Never Make a Space Movie Again" Wired (October 1, 2013)

External links

- Marooned at the Internet Movie Database

- Marooned at the TCM Movie Database

- Marooned at AllMovie

- Marooned at the American Film Institute Catalog