Market impact

In financial markets, market impact is the effect that a market participant has when it buys or sells an asset. It is the extent to which the buying or selling moves the price against the buyer or seller, i.e., upward when buying and downward when selling. It is closely related to market liquidity; in many cases "liquidity" and "market impact" are synonymous.

Especially for large investors, e.g., financial institutions, market impact is a key consideration that needs to be considered before any decision to move money within or between financial markets. If the amount of money being moved is large (relative to the turnover of the asset(s) in question), then the market impact can be several percentage points and needs to be assessed alongside other transaction costs (costs of buying and selling).

Market impact can arise because the price needs to move to tempt other investors to buy or sell assets (as counterparties), but also because professional investors may position themselves to profit from knowledge that a large investor (or group of investors) is active one way or the other. Some financial intermediaries have such low transaction costs that they can profit from price movements that are too small to be of relevance to the majority of investors.

The financial institution that is seeking to manage its market impact needs to limit the pace of its activity (e.g., keeping its activity below one-third of daily turnover) so as to avoid disrupting the price.

Measuring market impact

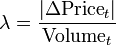

Several statistical measures exist. The most common and simplest is Kyle's Lambda, defined as the slope from regressing absolute returns to volume over some time window (often as short as 15 minutes). For very short periods, this reduces to simply

Volume is typically measured as turn-over or the value of shares traded, not the number. Under this measure, a highly liquid stock is one that experiences a small price change for a given level of trading volume.

Kyle's lambda is named from Albert Kyle's famous paper on market microstructure.[1]

Chart to Scalar

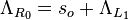

Chart to Scalar Theory, a purely theoretical result, says there is a correspondence between discrete buy and sell orders in the stock market volume and stock market geometry on the boundary. The boundary represents the charts which we can see. If you peel it back, there are buy and sell orders. The idea of the scalar is to encode the properties of the stock market into a scalar which represents a constraint of a hypothetical stock chart constrained by boundary conditions. [2]

valid for

valid for

Where  is the RHS (right hand side) three-component of volume, log-price differential, and scalar curvature for a rising market. If the market is expected to be flat

is the RHS (right hand side) three-component of volume, log-price differential, and scalar curvature for a rising market. If the market is expected to be flat

is the number of sell orders to be executed

is the number of sell orders to be executed

is the LHS (left hand side) three-component of volume, log-price differential, and scalar curvature for the resistor where

is the LHS (left hand side) three-component of volume, log-price differential, and scalar curvature for the resistor where

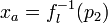

Solving for  gives the final price of the stock accounting for the extra sell orders.

gives the final price of the stock accounting for the extra sell orders.

The curvature of the LHS  can determine the optimal way to sell. Selling gradually yields a higher price than selling all at once if

can determine the optimal way to sell. Selling gradually yields a higher price than selling all at once if  is convex

is convex

A result from Chart to Scalar is that only a small excess of buy or sell orders from the total daily volume is needed for stocks to make large swings. Most trading volume is churn, or an even admixture of buys and sells.

Measuring market impact is, however, a very difficult task, and errors in estimating the market impact can highly impact the optimal strategy of trading.[3]

Unique challenges for microcap traders

Microcap and nanocap stocks are characterized by very low share prices and a relatively limited float and thin daily volume. Since these types of stocks have such limited float and are so thinly traded, these stocks are extremely volatile and susceptible to large price swings.

Microcap and nanocap traders often trade in and out of positions with huge blocks of shares to make quick money on speculative events. And therein lies a problem that many microcap and nanocap traders face—with so little float available, thin volume and large block orders, there is a shortage of shares. In many instances orders only get partially filled.

Example

Suppose an institutional investor places a limit order to sell 1 million shares of stock XYZ at $10.00 per share. Now a professional investor may see this, and place an order to short sell 1 million shares of XYZ at $9.99 per share.

- Stock XYZ rises in price to $9.99 and keeps going up past $10.00. The professional investor sells at $9.99 and covers his short position by buying from the institutional investor. His loss is limited to $0.01 per share.

- Stock XYZ rises in price to $9.99 and then comes back down. The professional investor sells at $9.99 and covers his short position when the stock declines. The professional investor can gain $.10 or more per share with very little risk. The institutional investor is unhappy, because he saw the market price rise to $9.99 and come back down, without his order getting filled.

Effectively, the institutional investor's large order has given an option to the professional investor. Institutional investors don't like this, because either the stock price rises to $9.99 and comes back down, without them having the opportunity to sell, or the stock price rises to $10.00 and keeps going up, meaning the institutional investor could have sold at a higher price.

See also

- Market impact cost – the transaction costs associated with price movements from the market impact

References

- ↑ Kyle, Albert (November 1985). "continuous Auctions and Insider Trading". Econometrica 56 (3): 129–176.

- ↑ title=Chart to Scalar Theory http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Stockequation/sandbox

- ↑ Moazeni, Somayeh; Thomas Coleman; Yuying Li (2010). "Optimal Portfolio Execution Strategies and Sensitivity to Price Impact Parameters". SIAM Journal on Optimization 20 (3): 1620–1654. doi:10.1137/080715901.

External links

- Market impact and trading profile of large trading orders in stock markets

- Robert Almgren; Chee Thum; Emmanuel Hauptmann; Hong Li (May 10, 2005). "Direct Estimation of Equity Market Impact" (pdf). Retrieved September 27, 2012.