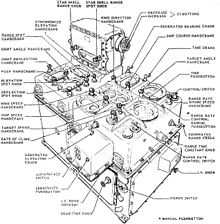

Mark I Fire Control Computer

The Mark 1, and later the Mark 1A, Fire Control Computer was a component of the Mark 37 Gun Fire Control System deployed by the United States Navy during World War II and up to 1969. It was used on a variety of ships, ranging from destroyers (one per ship) to battleships (four per ship). The Mark 37 system used tachymetric target motion prediction to compute a fire control solution. Weighing more than 3000 pounds (1363 kilograms),[1] the Mark 1 itself was installed in the plotting room, a water tight compartment that was located deep inside the ship's hull to provide as much protection against battle damage as was possible.

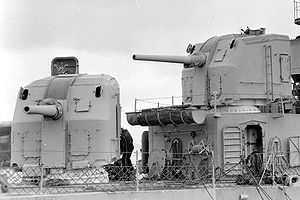

Essentially an electromechanical analog computer, the Mark 1 was electrically linked to the gun turrets and the Mark 37 gun director, the latter mounted as high on the superstructure as possible to afford maximum visual and radar range. The gun director was equipped with both optical and radar range finding, and was able to rotate on a small barbette-like structure. Using the range finders, the director was able to produce a continuously varying set of outputs, referred to as line-of-sight (LOS) data, that were electrically relayed to the Mark 1 via synchro motors. The LOS data provided the target's present range, bearing, and in the case of aerial targets, altitude. Additional inputs to the Mark 1 were continuously generated from the stable element, a gyroscopic device that reacted to the roll and pitch of the ship, the pitometer log, which measured the ship's speed through the water, and an anemometer, which provided wind speed and direction.

In "Plot" (the plotting room), a team of sailors stood around the 4-foot-tall (1.2 m) Mark 1 and continuously monitored its operation. They would also be responsible for calculating and entering the average muzzle velocity of the projectiles to be fired before action started. This calculation was based on the type of propellant to be used and its temperature, the projectile type and weight, and the number of rounds fired through the guns to date.

Given these inputs, the Mark 1 automatically computed the lead angles to the future position of the target at the end of the projectile's time of flight, adding in corrections for gravity, relative wind, the magnus effect of the spinning projectile, and parallax, the latter compensation necessary because the guns themselves were widely displaced along the length of the ship. Lead angles and corrections were added to the LOS data to generate the line-of-fire (LOF) data. The LOF data, bearing and elevation, as well as the projectile's fuze time, was sent to the turrets by synchro motors, whose motion actuated hydraulic machinery to aim the guns.

Once the system was "locked" on the target, it produced a continuous fire control solution. While these fire control systems greatly improved the long-range accuracy of ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore gunfire, especially on heavy cruisers and battleships, it was in the anti-aircraft warfare mode that the Mark 1 made the greatest contribution. However, the anti-aircraft value of analog computers such as the Mark 1 was greatly reduced with the introduction of jet aircraft, where the relative motion of the target became such that the computer's mechanism could not react quickly enough to produce accurate results.

The design of the post war Mark 1A may have been influenced by the Bell Labs Mark 8, Fire Control Computer which was developed as an all electrical computer, incorporating technology from the M9 gun data computer as a safeguard to ensure adequate supplies of fire control computers for the USN during WW2.[2] Surviving Mark 1 computers were upgraded to the Mark 1A standard after World War II ended.

Digital fire control computers were not introduced until the age of minicomputers in the mid-1970s.

See also

- Ship gun fire-control system

- Admiralty Fire Control Table

- High Angle Control System

- Gun data computer

References

- ↑ Gallagher, Sean. "Gears of war: When mechanical analog computers ruled the waves". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ Annals of the History of Computing, Volume 4, Number 3, July 1982 Electrical Computers for Fire Control, p218-46 W. H. C. Higgins, B. D. Holbrook, and J. W. Emling "...The development model of the Mark 8 (Figures 9 and 10) was delivered to the Naval Research Laboratory Annex at North Beach, Maryland, on February 15, 1944, whereupon extensive comparison tests of it and the Mark 1 were made, using both the Mark 37 and the Bell Labs Mark 7 radar as tracking devices. These tests were primarily photo-data runs, with actual aircraft (usually executing ordered manoeuvres) as targets; firing tests were not practicable at North Beach. These tests indicated that the two machines were comparable in the accuracy of the gun orders delivered, except in regions where mathematical approximations inherent in the design of the Mark1 sometimes resulted in substantial errors. (The Mark 8 geometry was substantially free of such errors.) It was also found that the Mark 8 reached solution much faster than the Mark 1. Since one of the drawbacks observed in fleet experience with the Mark 1 was its sluggishness, it was decided to attempt to modify the Mark 1 in accordance with the principles of the Mark 8 to obtain a faster solution time..."p232