Mariner 10

Artist's impression of the Mariner 10 mission. | |

| Mission type | Planetary exploration |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| COSPAR ID | 1973-085A[1] |

| SATCAT № | 6919[1] |

| Mission duration | 1 year, 4 months, 12 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Launch mass | 502.9 kilograms (1,109 lb) |

| Power | 820 watts (at Venus encounter) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | November 3, 1973, 05:45:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Atlas SLV-3D Centaur-D1A |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-36B |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Decommissioned |

| Deactivated | March 24, 1975 |

| Flyby of Venus | |

| Closest approach | February 5, 1974 |

| Distance | 5,768 kilometers (3,584 mi) |

| Flyby of Mercury | |

| Closest approach | March 29, 1974 |

| Distance | 704 kilometers (437 mi) |

| Flyby of Mercury | |

| Closest approach | September 21, 1974 |

| Distance | 48,069 kilometers (29,869 mi) |

| Flyby of Mercury | |

| Closest approach | March 16, 1975 |

| Distance | 327 kilometers (203 mi) |

Mariner 10 was an American robotic space probe launched by NASA on November 3, 1973, to fly by the planets Mercury and Venus.

Mariner 10 was launched approximately two years after Mariner 9 and was the last spacecraft in the Mariner program (Mariner 11 and 12 were allocated to the Voyager program and redesignated Voyager 1 and Voyager 2).

The mission objectives were to measure Mercury's environment, atmosphere, surface, and body characteristics and to make similar investigations of Venus. Secondary objectives were to perform experiments in the interplanetary medium and to obtain experience with a dual-planet gravity assist mission. Mariner 10's science team was led by Bruce C. Murray at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[2]

Design and trajectory

Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft to make use of an interplanetary gravitational slingshot maneuver, using Venus to bend its flight path and bring its perihelion down to the level of Mercury's orbit.[3] This maneuver, inspired by the orbital mechanics calculations of the Italian scientist Giuseppe Colombo, put the spacecraft into an orbit that repeatedly brought it back to Mercury. Mariner 10 used the solar radiation pressure on its solar panels and its high-gain antenna as a means of attitude control during flight, the first spacecraft to use active solar pressure control. The Mariner 10 spacecraft was manufactured by Boeing.[4]

Instruments

Mariner 10 instruments included:

- Twin telescope/cameras with digital tape recorder

- Ultraviolet spectrometer

- Infrared radiometer

- Solar plasma

- Charged particles

- Magnetic fields

- Radio occultation

- Celestial mechanics

The imaging system, the Television Photography Experiment, consisted of two 15 cm (5.9″) Cassegrain telescopes feeding vidicon tubes.[5] The main telescope could be bypassed to a smaller wide angle optic, but using the same tube.[5] It had an 8-position filter wheel, with one position occupied by a mirror for the wide-angle bypass.[5] The system returned about 7000 photographs of Mercury and Venus during Mariner 10's flybys.[5]

Departing the Earth–Moon system

During its first week of flight, Mariner 10 tested its camera system by returning five photographic mosaics of Earth and six of the Moon. It also obtained photographs of the north polar region of the moon where prior coverage was poor. These provided a basis for cartographers to update lunar maps and improve the lunar control net.[6]

Cruise to Venus

A trajectory correction maneuver was made on November 13, 1973. Immediately afterwards, the star-tracker locked onto a bright flake of paint which had come off the spacecraft and lost tracking on the guide star Canopus. An automated safety protocol recovered Canopus, but the problem of flaking paint recurred throughout the mission. The on-board computer also experienced unscheduled resets occasionally, which necessitated reconfiguring the clock sequence and subsystems. Periodic problems with the high-gain antenna also occurred during the cruise. In January 1974, Mariner 10 made ultraviolet observations of Comet Kohoutek. Another mid-course correction was made on January 21, 1974.

Venus flyby

The spacecraft passed Venus on February 5, 1974, the closest approach being 5,768 km at 17:01 UT. Using a near-ultraviolet filter, it photographed the Cytherean chevron clouds and performed other atmospheric studies. It was discovered that extensive cloud detail could be seen through Mariner's ultraviolet camera filters. Venus's cloud cover is nearly featureless in visible light. Earth-based ultra-violet observation did reveal some indistinct blotching even before Mariner 10, but the detail seen by Mariner was a surprise to most researchers.

-

Venus encounter

-

Venus in real colors, processed from clear and blue filtered Mariner 10 images

-

Mariner photograph of Venus in ultraviolet light

First Mercury flyby

The first Mercury encounter took place at 20:47 UT on March 29, 1974, at a range of 703 kilometers (437 mi), passing on the shadow side.[3]

-

First Mercury encounter

-

6 hours before closest approach

-

.jpg)

6 hours after closest approach

Second Mercury flyby

After looping once around the Sun while Mercury completed two orbits, Mariner 10 flew by Mercury again on September 21, 1974, at a more distant range of 48,069 km (29,869 mi) below the southern hemisphere.[3]

-

Second Mercury encounter

-

Mosaic of images from the second encounter, covering the equator to the south pole

Third Mercury flyby

After losing roll control in October 1974, a third and final encounter, the closest to Mercury, took place on March 16, 1975, at a range of 327 km (203 mi), passing almost over the north pole.[3]

-

Third Mercury encounter

-

Mercury in color

-

Mercury in black and white

-

Mercury in false-color

-

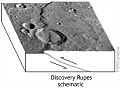

A prominent scarp, Discovery Rupes, photographed during first flyby

-

Representation of the thrust fault at Discovery Rupes

-

Old basin, 190 km in diameter, filled by smooth plains. The basin's hummocky rim is partly degraded and cratered by later events

End of mission

With its maneuvering gas just about exhausted, Mariner 10 started another orbit of the Sun. Engineering tests were continued until March 24, 1975,[3] when final depletion of the nitrogen supply was signaled by the onset of an un-programmed pitch turn. Commands were sent immediately to the spacecraft to turn off its transmitter, and radio signals to Earth ceased.

Mariner 10 is still orbiting the Sun, although its electronics have probably been damaged by the Sun's radiation.[7] Dave Williams of NASA's National Space Science Data Center said in 2005: "Mariner 10 has not been tracked or spotted from Earth since it stopped transmitting. We can only assume it's still orbiting [the Sun], but the only way it would not be orbiting would be if it had been hit by an asteroid or gravitationally perturbed by a close encounter with a large body. The odds of that happening are extremely small, so it is assumed to still be in orbit."

Discoveries

During its flyby of Venus, Mariner 10 discovered evidence of rotating clouds and a very weak magnetic field.

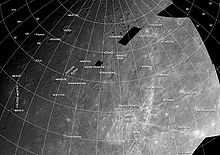

The spacecraft flew past Mercury three times. Owing to the geometry of its orbit – its orbital period was almost exactly twice Mercury's – the same side of Mercury was sunlit each time, so it was only able to map 40–45% of Mercury’s surface, taking over 2,800 photos. It revealed a more or less Moon-like surface. It thus contributed enormously to our understanding of Mercury, whose surface had not been successfully resolved through telescopic observation. The regions mapped included most or all of the Shakespeare, Beethoven, Kuiper, Michelangelo, Tolstoj, and Discovery quadrangles, half of Bach and Victoria quadrangles, and small portions of Solitudo Persephones (later Neruda), Liguria (later Raditladi), and Borealis quadrangles.[8]

Mariner 10 also discovered that Mercury has a tenuous atmosphere consisting primarily of helium, as well as a magnetic field and a large iron-rich core. Its radiometer readings suggested that Mercury has a night time temperature of −183 °C (−297 °F) and maximum daytime temperatures of 187 °C (369 °F).

Planning for MESSENGER, a spacecraft that surveyed Mercury until 2015, relied extensively on data and information collected by Mariner 10.

Mariner 10 Commemoration

On February 10, 1975, the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp featuring the Mariner 10 space probe. The 10-cent Mariner 10 commemorative stamp was issued on April 4, 1975, at Pasadena, California.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Mariner 10". US National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ Schudel, Matt (30 August 2013). "Bruce C. Murray, NASA space scientist, dies at 81". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Mariner 10". Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Mariner 10 Quicklook". Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 NASA/NSSDC - Mariner 10 - Television Photography

- ↑ The Voyage of Mariner 10: Mission to Venus and Mercury (NASA SP-424) 1978 pages 47–53.

- ↑ Mariner 10 (2006) Views of the Solar System

- ↑ Schaber, Gerald G.; McCauley, John F. Geologic Map of the Tolstoj (H-8) Quadrangle of Mercury (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. USGS Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I–1199, as part of the Atlas of Mercury, 1:5,000,000 Geologic Series. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

External links

- The Voyage of Mariner 10: Mission to Venus and Mercury (NASA SP-424) 1978 This is an entire book about Mariner 10, with all pictures and diagrams, on-line! Scroll down to click on the "Table of Contents" link. PDF version

- 'Mariner 10', NASA's 1973–75 Venus/Mercury Mission

- Mariner 10 image archive

- Mariner 10 Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Calibrated images from the Mariner 10 mission to Mercury and Venus

- Master Catalog entry for Mariner 10 at the National Space Science Data Center

- Boeing: History – Products – Boeing Mariner 10 Spacecraft

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||