Marilyn Monroe

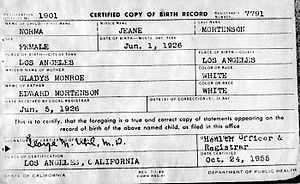

| Marilyn Monroe | |

|---|---|

|

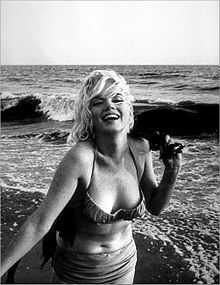

Monroe circa early 1950s | |

| Born |

Norma Jeane Mortenson June 1, 1926 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died |

August 5, 1962 (aged 36) Brentwood, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

Cause of death | Barbiturate overdose |

Resting place | Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, Westwood, Los Angeles |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Actress, model, singer, film producer |

| Years active | 1945–62 |

| Notable work | Niagara, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, River of No Return, The Seven Year Itch, Some Like It Hot, The Misfits |

| Religion |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Golden Globe Awards | |

| |

| AFI Awards | |

| AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars (1999) | |

| Signature |

|

Marilyn Monroe[1][2] (born Norma Jeane Mortenson; June 1, 1926 – August 5, 1962)[3] was an American actress, model, and singer, who became a major sex symbol, starring in a number of commercially successful motion pictures during the 1950s and early 1960s.[4]

After spending much of her childhood in foster homes, Monroe began a career as a model, which led to a film contract in 1946 with Twentieth Century-Fox. Her early film appearances were minor, but her performances in The Asphalt Jungle and All About Eve (both 1950) drew attention. By 1952 she had her first leading role in Don't Bother to Knock[5] and 1953 brought a lead in Niagara, a melodramatic film noir that dwelt on her seductiveness. Her "dumb blonde" persona was used to comic effect in subsequent films such as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) and The Seven Year Itch (1955). Limited by typecasting, Monroe studied at the Actors Studio to broaden her range. Her dramatic performance in Bus Stop (1956) was hailed by critics and garnered a Golden Globe nomination. Her production company, Marilyn Monroe Productions, released The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), for which she received a BAFTA Award nomination and won a David di Donatello award. She received a Golden Globe Award for her performance in Some Like It Hot (1959). Monroe's last completed film was The Misfits (1961), co-starring Clark Gable, with a screenplay written by her then-husband, Arthur Miller.

The final years of Monroe's life were marked by illness, personal problems, and a reputation for unreliability and being difficult to work with. The circumstances of her death, from an overdose of barbiturates, have been the subject of conjecture. Though officially classified as a "probable suicide", the possibilities of an accidental overdose or a homicide have not been ruled out. In 1999, Monroe was ranked as the sixth-greatest female star of all time by the American Film Institute. In the decades following her death, she has often been cited as both a pop and a cultural icon as well as the quintessential American sex symbol.[6][7][8] In 2009, TV Guide Network named her No. 1 in Film's Sexiest Women of All Time.[9]

Family and early life

Marilyn Monroe was born on June 1, 1926, in Los Angeles County Hospital[10] as Norma Jeane Mortenson (soon after changed to Baker), the third child born to Gladys Pearl Baker (née Monroe, May 27, 1902 – March 11, 1984).[11] Monroe's birth certificate names the father as Martin Edward Mortensen with his residence stated as "unknown".[12] The name Mortenson is listed as her surname on the birth certificate, although Gladys immediately had it changed to Baker, the surname of her first husband and which she still used. Martin's surname was misspelled on the birth certificate leading to more confusion on who her actual father was. Gladys Baker had married a Martin E. Mortensen in 1924, but they had separated before Gladys' pregnancy.[13] Several of Monroe's biographers suggest that Gladys Baker used his name to avoid the stigma of illegitimacy.[14] Mortensen died at the age of 85, and Monroe's birth certificate, together with her parents' marriage and divorce documents, were discovered. The documents showed that Mortensen filed for divorce from Gladys on March 5, 1927, and it was finalized on October 15, 1928.[15][16] Throughout her life, Marilyn Monroe denied that Mortensen was her father.[13] Marilyn said that, when she was a child, she had been shown a photograph of a man that Gladys identified as her father, Charles Stanley Gifford. She remembered that he had a thin mustache and somewhat resembled Clark Gable, and that she had amused herself by pretending that Gable was her father.[13][17]

Gladys was mentally unstable and financially unable to care for the young Norma Jeane, so she placed her with foster parents Albert and Ida Bolender of Hawthorne, California, where she lived until she was seven. One day, Gladys visited and demanded that the Bolenders return Norma Jeane to her. Ida refused, as she knew Gladys was unstable and the situation would not benefit her young daughter. Gladys pulled Ida into the yard, then quickly ran back to the house and locked herself in. Several minutes later, she walked out with one of Albert Bolender's military duffel bags. To Ida's horror, Gladys had stuffed a screaming Norma Jeane into the bag, zipped it up, and was carrying it out with her. Ida charged toward her, and their struggle split the bag apart, dumping out Norma Jeane, who wept loudly as Ida grabbed her and pulled her back inside the house, away from Gladys.[18] In 1933, Gladys bought a house and brought Norma Jeane to live with her. A few months later, Gladys began a series of mental episodes that would plague her for the rest of her life. In her autobiography, My Story, Monroe recalls her mother "screaming and laughing" as she was forcibly removed to the State Hospital in Norwalk.

Norma Jeane was declared a ward of the state. Gladys's best friend, Grace McKee, became her guardian. Grace told Monroe that some day she would become a movie star. Grace was captivated by Jean Harlow, and would let Norma Jeane wear makeup and take her out to get her hair curled. They went to the movies together, forming the basis for Norma Jeane's fascination with the cinema and the stars on screen. When Norma Jeane was 9, McKee married Ervin Silliman "Doc" Goddard in 1935, and subsequently sent Monroe to the Los Angeles Orphans Home (later renamed Hollygrove), followed by a succession of foster homes.[19] While at Hollygrove, several families were interested in adopting her, but reluctance on Gladys' part to sign adoption papers thwarted those attempts. In 1937, Monroe moved back into Grace and Doc Goddard's house, joining Doc's daughter from a previous marriage. Due to Doc's frequent attempts to sexually assault Norma Jeane, this arrangement did not last long.

Grace sent Monroe to live with her great-aunt, Olive Brunings, in Compton, California; this was also a brief stint ended by an assault when one of Olive's sons had attacked the now middle-school-aged girl. Taraborrelli, Daniel Schechter, and Erica Willheim have questioned whether at least some of Monroe's later behavior (i.e., hyper-sexuality, sleep disturbances, substance abuse, disturbed interpersonal relationships), was a manifestation of the effects of childhood sexual abuse in the context of her already problematic relationships with her psychiatrically ill mother and subsequent caregivers.[20][21] In early 1938, Grace sent her to live with another aunt, Ana Lower, who lived in the Van Nuys district of Los Angeles. Years later, she would reflect fondly about the time that she spent with Lower, whom she affectionately called "Aunt Ana". She would explain that it was one of the few times in her life when she felt truly stable. As she aged, Lower developed serious health problems.

In 1942, Monroe moved back to Grace and Doc Goddard's house. While attending Van Nuys High School, she met a neighbor's son, James "Jim" Dougherty, and began a relationship with him.[22][23][24] Several months later, Grace and Doc Goddard relocated to West Virginia, where Doc had received a lucrative job offer. Although it was never explained why, they decided not to take Monroe with them. A neighborhood family offered to adopt Monroe, but Gladys rejected the offer. With few options left, Grace approached Dougherty's mother and suggested that Jim marry Monroe so that she would not have to return to an orphanage or foster care. Jim was initially reluctant, but he finally relented and married her in a ceremony arranged by Ana Lower. During this period, Monroe briefly supported her family as a homemaker. In 1943, during World War II, Dougherty enlisted in the Merchant Marine. He was initially stationed on Santa Catalina Island off California's coast, and Monroe lived with him there in the town of Avalon for several months before he was shipped out to the Pacific. Frightened that he might not come back alive, Monroe begged him to try and get her pregnant before he left. Dougherty disagreed, feeling that she was too young to have a baby, but he promised that they would revisit the subject when he returned home. Subsequently, Monroe moved in with Dougherty's mother.

Career

Early work: 1945–1947

While Dougherty served in the Merchant Marine, his wife began working in the Radioplane Munitions Factory, mainly spraying airplane parts with fire retardant and inspecting parachutes. The factory was owned by movie star Reginald Denney.[25] During that time, David Conover of the U.S. Army Air Forces' First Motion Picture Unit was sent to the factory by his commanding officer, future U.S. president Captain Ronald Reagan to shoot morale-boosting photographs for Yank, the Army Weekly magazine of young women helping the war effort.[26] He noticed her and snapped a series of photographs, none of which appeared in Yank magazine,[27] although some still claim this to be the case. He encouraged her to apply to The Blue Book Modeling Agency. She signed with the agency and began researching the work of Jean Harlow and Lana Turner. She was told that they were looking for models with lighter hair, so Norma Jeane bleached her brunette hair a golden blonde.[28]

Norma Jeane became one of Blue Book's most successful models; she appeared on dozens of magazine covers. Her successful modeling career brought her to the attention of Ben Lyon, a 20th Century Fox executive, who arranged a screen test for her. Lyon was impressed and commented, "It's Jean Harlow all over again."[29] She was offered a standard six-month contract with a starting salary of $125 per week. Lyon did not like the name Norma Jeane and chose "Carole Lind" as a stage name, after Carole Lombard and Jenny Lind, but he soon decided it was not an appropriate choice. Monroe was invited to spend the weekend with Lyon and his wife Bebe Daniels at their home. It was there that they decided to find her a new name. Following her idol Jean Harlow, she decided to choose her mother's maiden name of Monroe. Several variations such as Norma Jeane Monroe and Norma Monroe were tried and initially "Jeane Monroe" was chosen. Eventually, Lyon decided Jeane and variants were too common, and he decided on a more alliterative sounding name. He suggested "Marilyn", commenting that she reminded him of Marilyn Miller. Monroe was initially hesitant because Marilyn was the contraction of the name Mary Lynn, a name she did not like.[30] Lyon, however, felt that the name "Marilyn Monroe" was sexy, had a "nice flow", and would be "lucky" due to the double "M".[31]

In September 1946, Monroe filed for divorce. Dougherty, served with divorce papers while aboard a ship on the Yangtze river in China, reported that he tried to persuade his wife against the divorce upon his return, but she refused. In a 1984 interview, he claimed, "She wanted to sign a contract with [20th Century] Fox and it said she couldn't be married -- they didn't want a pregnant starlet."[23]

During her first few months at 20th Century Fox, Monroe had no speaking roles in any films but, alongside other new contract players, took singing, dancing and other classes. She appeared as an extra in some movies, but no exact list exists; some film buffs claim she appears in the musical comedies The Shocking Miss Pilgrim and You Were Meant for Me, and in the Western, Green Grass of Wyoming, but these are unconfirmed.[32] Her first credited role was as a waitress in Dangerous Years, released in December 1947, in which she had nine short lines. In March 1948, she appeared in a bit part as Betty in Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! (released after Dangerous Years but filmed before). Dressed in a pinafore and walking down the steps of a church, she says, "Hi, Rad" to the main character, played by June Haver, who responds, "Hi, Betty." After Monroe's stardom, 20th Century Fox began claiming that Monroe's only line in the film had been cut out, an anecdote Monroe repeated on Person to Person in 1955, but film historian James Haspiel says her line is intact and she also appears in a shot paddling a canoe with another woman.[32]

Breakthrough: 1948–1951

In 1947, Monroe had been released from her contract with 20th Century Fox. She then met with Hollywood pin-up photographer Bruno Bernard, who photographed her at the Racquet Club of Palm Springs; and it was at the Racquet Club where she met Hollywood talent agent Johnny Hyde.[33] In 1948, Monroe signed a six-month contract with Columbia Pictures and was introduced to the studio's head drama coach Natasha Lytess, who became her acting coach for several years.[34] Monroe was soon cast in a major role in the low-budget musical Ladies of the Chorus (1948). Monroe was reviewed as one of the film's bright spots, although the film enjoyed only moderate success.[35] During her short stint at Columbia, studio head Harry Cohn softened her appearance somewhat by correcting a slight overbite she had.

After the release of the poorly reviewed Ladies of the Chorus and being dropped by Columbia, Monroe had to struggle to find work. She particularly wanted film work, and when the offers didn't come, she returned to modeling. In 1949, she caught the eye of photographer Tom Kelley, who convinced her to pose nude. Monroe was laid out on a large fabric of red silk and posed for countless shots. She was paid $50 and signed the model release form as "Mona Monroe". This was the only time that Monroe was paid for her nude posing.

Soon thereafter she had a small walk-on role in the Marx Brothers film Love Happy (1949). Monroe impressed the producers, who sent her to New York City to be featured in the film's promotional campaign.[36] While on the East Coast, she and Andre de Dienes, one of Norma Jeane's early photographers, shot a famous series of pin-up shots of her at Long Island's Tobay Beach, in Oyster Bay, New York.[37]

After signing on with Johnny Hyde, Monroe had brief roles in three films, A Ticket to Tomahawk, Right Cross, and The Fireball, all of which were released in 1950 and brought no attention to her career. Hyde soon thereafter arranged for her to audition for John Huston, who cast her in the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer drama The Asphalt Jungle as the young mistress of an aging criminal. Her performance brought strong reviews,[36] and was seen by the writer and director, Joseph Mankiewicz. He accepted Hyde's suggestion to cast Monroe in a small comedic role in All About Eve as Miss Caswell, an aspiring actress, described by another character, played by George Sanders, as a student of "The Copacabana School of Dramatic Art". Mankiewicz later commented that he had seen an innocence in her that he found appealing, and that this had confirmed his belief in her suitability for the role.[38] Following Monroe's success in these roles, Hyde negotiated a seven-year contract for her with 20th Century Fox, shortly before his death in December 1950.[39] It was at some time during this 1949–1950 period that Hyde arranged for her to have a slight bump of cartilage removed from her somewhat bulbous nose which further softened her appearance and accounts for the slight variation in look she had in films after 1950.

In 1951, Monroe enrolled at University of California, Los Angeles, where she studied literature and art appreciation.[40] During this time Monroe had minor parts in four films: the low-budget drama Home Town Story with Jeffrey Lynn and Alan Hale, Jr., and three comedies: As Young as You Feel with Monty Woolley and Thelma Ritter; Love Nest with June Haver and William Lundigan; and Let's Make It Legal with Claudette Colbert and Macdonald Carey, all of which were filmed on a moderate budget and only became mildly successful.[41] In March 1951, she appeared as a presenter at the 23rd Academy Awards ceremony.[42] In 1952, Monroe appeared on the cover of Look magazine wearing a Georgia Tech sweater as part of an article celebrating female enrollment to the school's main campus. In the early 1950s, Monroe unsuccessfully auditioned for the role of Daisy Mae in a proposed Li'l Abner television series based on the Al Capp comic strip.

Leading films: 1952–1955

In March 1952, Monroe faced a possible scandal when two of her nude photos from her 1949 session with photographer Tom Kelley were featured on calendars. The press speculated about the identity of the anonymous model and commented that she closely resembled Monroe. As the studio discussed how to deal with the problem, Monroe suggested that she should simply admit that she had posed for the photographs but emphasize that she had done so only because she had no money to pay her rent.[43] She gave an interview in which she discussed the circumstances that led to her posing for the photographs, and the resulting publicity elicited a degree of sympathy for her plight as a struggling actress.[43] One of these photographs was published in the first issue of Playboy in December 1953, making Monroe the first Playmate of the Month.[44] Playboy's editor Hugh Hefner chose what he deemed the "sexiest" image, a previously unused nude study of Monroe stretched with an upraised arm on a red velvet background from 1949.[45] The heavy promotion centered around Monroe's nudity on the already famous calendar, together with the tease marketing, made the new Playboy magazine a success.[46][47]

She made her first appearance on the cover of Life magazine in April 1952, where she was described as "The Talk of Hollywood".[48] The following year, she was photographed by noted Life magazine photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt, considered "The father of photojournalism."[49][50] He photographed Monroe on the patio of her Hollywood home. Many of the images from that sitting have been reproduced in numerous subsequent publications and by Life magazine.[51][52] Monroe was pleased with his images of her, later telling him, "You made a palace out of my patio."[53]

Stories of her childhood and upbringing portrayed her in a sympathetic light: a cover story for the May 1952 edition of True Experiences magazine showed a smiling and wholesome Monroe beside a caption that read, "Do I look happy? I should—for I was a child nobody wanted. A lonely girl with a dream—who awakened to find that dream come true. I am Marilyn Monroe. Read my Cinderella story."[54] It was also during this time that she began dating baseball player Joe DiMaggio. A photograph of DiMaggio visiting Monroe at the 20th Century Fox studio was printed in newspapers throughout the United States, and reports of a developing romance between them generated further interest in Monroe.[55]

Four films in which Monroe was featured were released beginning in 1952. She had been lent to RKO Studios to appear in a supporting role in Clash by Night, a Barbara Stanwyck drama, directed by Fritz Lang.[56] Released in June 1952, the film was popular with audiences, with much of its success credited to curiosity about Monroe, who received generally favorable reviews from critics.[57]

This was followed by two films released in July, the comedy We're Not Married!, and the drama Don't Bother to Knock. We're Not Married! featured Monroe as a beauty pageant contestant. Variety described the film as "lightweight". Its reviewer commented that Monroe was featured to full advantage in a bathing suit, and that some of her scenes suggested a degree of exploitation.[58] In Don't Bother to Knock she played the starring role[59] of a babysitter who threatens to attack the child in her care. The downbeat melodrama was poorly reviewed, although Monroe commented that it contained some of her strongest dramatic acting.[59] Monkey Business, a successful comedy directed by Howard Hawks starring Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers, was released in September and was the first movie in which Monroe appeared with platinum blonde hair.[60] In O. Henry's Full House for 20th Century Fox, released in August 1952, Monroe had a single one-minute scene with Charles Laughton, yet she received top billing alongside him and the film's other stars, including Anne Baxter, Farley Granger, Jean Peters and Richard Widmark.

Darryl F. Zanuck considered that Monroe's film potential was worth developing and cast her in Niagara, as a femme fatale scheming to murder her husband, played by Joseph Cotten.[61] During filming, Monroe's make-up artist Whitey Snyder noticed her stage fright (that would ultimately mark her behavior on film sets throughout her career); the director assigned him to spend hours gently coaxing and comforting Monroe as she prepared to film her scenes.[62] Reviews of the film dwelled on her sexuality, while noting that her acting was imperfect.[63]

Much of the critical commentary following the release of the film focused on Monroe's overtly sexual performance,[61] and a scene which shows Monroe (from the back) making a long walk toward Niagara Falls received frequent note in reviews.[64] After seeing the film, Constance Bennett reportedly quipped, "There's a broad with her future behind her."[65] Whitey Snyder also commented that it was during preparation for this film, after much experimentation, that Monroe achieved "the look, and we used that look for several pictures in a row ... the look was established."[64] While the film was a success, and Monroe's performance had positive reviews, her conduct at promotional events sometimes drew negative comments. Her appearance at the Photoplay awards dinner in a skin-tight gold lamé dress was criticized. Louella Parsons' newspaper column quoted Joan Crawford discussing Monroe's "vulgarity" and describing her behavior as "unbecoming an actress and a lady".[66] Monroe had previously received criticism for wearing a dress with a neckline cut almost to her navel when she acted as grand marshal at the Miss America Parade in September 1952.[67] A photograph from this event was used on the cover of the first issue of Playboy in December 1953.[44]

Monroe next replaced Betty Grable in the musical film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) co-starring Jane Russell and directed by Howard Hawks. Her role as Lorelei Lee, a gold-digging showgirl, required her to act, sing, and dance. The two stars became friends, with Russell describing Monroe as "very shy and very sweet and far more intelligent than people gave her credit for".[68] She later recalled that Monroe showed her dedication by rehearsing her dance routines each evening after most of the crew had left, but she arrived habitually late on set for filming. Realizing that Monroe remained in her dressing room due to stage fright, and that Hawks was growing impatient with her tardiness, Russell started escorting her to the set.[69]

At the Los Angeles premiere of the film, Monroe and Russell pressed their hand- and footprints in the wet concrete in the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theatre. Monroe received positive reviews and the film grossed more than double its production costs.[70] Her rendition of "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend" became associated with her. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes also marked one of the earliest films in which William Travilla dressed Monroe. Travilla dressed Monroe in eight of her films including Bus Stop, Don't Bother to Knock, How to Marry a Millionaire, River of No Return, There's No Business Like Show Business, Monkey Business, and The Seven Year Itch.[71] How to Marry a Millionaire was a comedy about three models scheming to attract wealthy husbands. The film teamed Monroe with Betty Grable (whom she replaced in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes) and Lauren Bacall, and was directed by Jean Negulesco.[72] The producer and scriptwriter, Nunnally Johnson, said that it was the first film in which audiences "liked Marilyn for herself [and that] she diagnosed the reason very shrewdly. She said that it was the only picture she'd been in, in which she had a measure of modesty... about her own attractiveness."[73]

Monroe's films of this period established her "dumb blonde" persona and contributed to her popularity. In 1953 and 1954, she was listed in the annual "Quigley Poll of the Top Ten Money Making Stars", which was compiled from the votes of movie exhibitors throughout the United States for the stars that had generated the most revenue in their theaters over the previous year.[74] "I want to grow and develop and play serious dramatic parts. My dramatic coach, Natasha Lytess, tells everybody that I have a great soul, but so far nobody's interested in it." Monroe told the New York Times.[75] She saw a possibility in 20th Century Fox's upcoming film, The Egyptian, but was rebuffed by Darryl F. Zanuck who refused to screen test her.[76]

Instead, she was assigned to the western River of No Return, opposite Robert Mitchum. Director Otto Preminger resented Monroe's reliance on Natasha Lytess, who coached Monroe and announced her verdict at the end of each scene. Eventually Monroe refused to speak to Preminger, and Mitchum had to mediate.[77] Of the finished product, she commented, "I think I deserve a better deal than a grade Z cowboy movie in which the acting finished second to the scenery and the CinemaScope process."[78] In late 1953 Monroe was scheduled to begin filming The Girl in Pink Tights with Frank Sinatra. When she failed to appear for work, 20th Century Fox suspended her.[79]

International success: 1954–1957

Monroe and Joe DiMaggio were married in San Francisco on January 14, 1954. They traveled to Japan soon after, combining a honeymoon with a business trip previously arranged by DiMaggio. For two weeks she took a secondary role to DiMaggio as he conducted his business, having told a reporter, "Marriage is my main career from now on."[80] Monroe then traveled alone to Korea where she performed for 13,000 American Marines over a three-day period. She later commented that the experience had helped her overcome a fear of performing in front of large crowds.[81]

Returning to Hollywood in March 1954, Monroe settled her disagreement with 20th Century Fox and appeared in the musical There's No Business Like Show Business. The film failed to recover its production costs[78] and was poorly received. Ed Sullivan described Monroe's performance of the song "Heat Wave" as "one of the most flagrant violations of good taste" he had witnessed.[82] Time magazine compared her unfavorably to co-star Ethel Merman, while Bosley Crowther for The New York Times said that Mitzi Gaynor had surpassed Monroe's "embarrassing to behold" performance.[83] The reviews echoed Monroe's opinion of the film. She had made it reluctantly, on the assurance that she would be given the starring role in the film adaptation of the Broadway hit The Seven Year Itch.[84]

Monroe won one of her most notable film roles as the Girl in The Seven Year Itch. In September 1954, she shot a skirt-blowing key scene for the picture on Lexington Avenue at 52nd Street in New York City. In it, she stands with her co-star, Tom Ewell, while the air from a subway grating blows her skirt up. A large crowd watched as director Billy Wilder ordered the scene to be refilmed many times. Joe DiMaggio was reported to have been present and infuriated by the spectacle.[85] After a quarrel, witnessed by journalist Walter Winchell, the couple returned to California where they avoided the press for two weeks, until Monroe announced that they had separated.[86] Their divorce was granted in November 1954.[87] The filming was completed in early 1955, and after refusing what she considered to be inferior parts in The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing and How to Be Very, Very Popular, Monroe decided to leave Hollywood on the advice of Milton Greene. The Seven Year Itch was released and became a success, earning an estimated $8 million.[88] Monroe received positive reviews for her performance and was in a strong position to negotiate with 20th Century Fox.[88] On New Year's Eve 1955, they signed a new contract which required Monroe to make four films over a seven-year period. The newly formed Marilyn Monroe Productions would be paid $100,000 plus a share of profits for each film. In addition to being able to work for other studios, Monroe had the right to reject any script, director or cinematographer she did not approve of.[89][90]

Milton Greene had first met Monroe in 1953 when he was assigned to photograph her for Look magazine. While many photographers tried to emphasize her sexy image, Greene presented her in more modest poses, and she was pleased with his work. As a friendship developed between them, she confided to him her frustration with her 20th Century Fox contract and the roles she was offered and he quoted her once as saying "I just want people to be happy to see me." Her salary for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes amounted to $18,000, while freelancer Jane Russell was paid more than $100,000.[91] Greene agreed that she could earn more by breaking away from 20th Century Fox. He gave up his job in 1954, mortgaged his home to finance Monroe, and allowed her to live with his family as they determined the future course of her career.[92]

On April 8, 1955, veteran journalist Edward R. Murrow interviewed Greene and his wife Amy, as well as Monroe, at the Greenes' home in Connecticut on a live telecast of the CBS program Person to Person. The kinescope of the telecast has been released on home video.[93]

Truman Capote introduced Monroe to Constance Collier, who gave her acting lessons. She felt that Monroe was not suited to stage acting, but possessed a "lovely talent" that was "so fragile and subtle, it can only be caught by the camera". After only a few weeks of lessons, Collier died.[94] Monroe had met Paula Strasberg and her daughter Susan on the set of There's No Business Like Show Business,[95] and had previously said that she would like to study with Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. In March 1955, Monroe met with Cheryl Crawford, one of the founders of the Actors Studio, and convinced her to introduce her to Lee Strasberg, who interviewed her the following day and agreed to accept her as a student.[96]

In May 1955, Monroe started dating playwright Arthur Miller; they had met in Hollywood in 1950 and when Miller discovered she was in New York, he arranged for a mutual friend to reintroduce them.[97] On June 1, 1955, Monroe's birthday, Joe DiMaggio accompanied Monroe to the premiere of The Seven Year Itch in New York City. He later hosted a birthday party for her, but the evening ended with a public quarrel, and Monroe left the party without him. A lengthy period of estrangement followed.[98][99] Throughout that year, Monroe studied with the Actors Studio, and found that one of her biggest obstacles was her severe stage fright. She was befriended by the actors Kevin McCarthy and Eli Wallach who each recalled her as studious and sincere in her approach to her studies, and noted that she tried to avoid attention by sitting quietly in the back of the class.[100] When Strasberg felt Monroe was ready to give a performance in front of her peers, Monroe and Maureen Stapleton chose the opening scene from Eugene O'Neill's Anna Christie, and although she had faltered during each rehearsal, she was able to complete the performance without forgetting her lines.[101] Kim Stanley later recalled that students were discouraged from applauding, but that Monroe's performance had resulted in spontaneous applause from the audience.[101] While Monroe was a student, Lee Strasberg commented, "I have worked with hundreds and hundreds of actors and actresses, and there are only two that stand out way above the rest. Number one is Marlon Brando, and the second is Marilyn Monroe."[101]

The first film to be made under the contract and production company was Bus Stop directed by Joshua Logan. Logan had studied under Constantin Stanislavski, approved of method acting, and was supportive of Monroe.[102] Monroe severed contact with her drama coach, Natasha Lytess, replacing her with Paula Strasberg, who became a constant presence during the filming of Monroe's subsequent films.[103]

In Bus Stop, Monroe played Chérie, a saloon singer with little talent who falls in love with a cowboy, Beauregard "Bo" Decker, played by Don Murray. Her costumes, make-up and hair reflected a character who lacked sophistication, and Monroe provided deliberately mediocre singing and dancing. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times proclaimed: "Hold on to your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress." In his autobiography, Movie Stars, Real People and Me, director Logan wrote, "I found Marilyn to be one of the great talents of all time... she struck me as being a much brighter person than I had ever imagined, and I think that was the first time I learned that intelligence and, yes, brilliance have nothing to do with education." Logan championed Monroe for an Academy Award nomination and complimented her professionalism until the end of his life.[104] Though not nominated for an Academy Award,[105] she received a Golden Globe nomination.

Bus Stop was followed by The Prince and the Showgirl directed by Laurence Olivier, who also co-starred. Prior to filming, Olivier praised Monroe as "a brilliant comedienne, which to me means she is also an extremely skilled actress". During filming in England he resented Monroe's dependence on her drama coach, Paula Strasberg, regarding Strasberg as a fraud whose only talent was the ability to "butter Marilyn up". He recalled his attempts at explaining a scene to Monroe, only to hear Strasberg interject, "Honey—just think of Coca-Cola and Frank Sinatra."[106] Olivier later commented that in the film "Marilyn was quite wonderful, the best of all."[107] Monroe's performance was hailed by critics, especially in Europe, where she won the David di Donatello, the Italian equivalent of an Academy Award, as well as the French Crystal Star Award. She was also nominated for a BAFTA. It was more than a year before Monroe began her next film. During her hiatus, she summered with Miller in Amagansett, New York. In 1956, she was pictured in Life magazine with Victor Mature greeting the Queen of the United Kingdom.[108] She suffered a miscarriage on August 1, 1957.[109][110]

Last films: 1958–1962

With Miller's encouragement she returned to Hollywood in August 1958 to star in Some Like It Hot. The film was directed by Billy Wilder and co-starred Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis. Wilder had experienced Monroe's tardiness, stage fright, and inability to remember lines during production of The Seven Year Itch. However her behavior was now more hostile, and was marked by refusals to participate in filming and occasional outbursts of profanity.[111] Monroe consistently refused to take direction from Wilder, or insisted on numerous retakes of simple scenes until she was satisfied.[112] She developed a rapport with Lemmon, but she disliked Curtis after hearing that he had described their love scenes as "like kissing Hitler".[113] Curtis later stated that the comment was intended as a joke.[114] During filming, Monroe discovered that she was pregnant. She suffered another miscarriage in December 1958, as filming was completed.[115]

Some Like it Hot became a resounding success, and was nominated for six Academy Awards. Monroe was acclaimed for her performance and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress - Motion Picture Musical or Comedy. Wilder commented that the film was the biggest success he had ever been associated with.[116] He discussed the problems he encountered during filming, saying "Marilyn was so difficult because she was totally unpredictable. I never knew what kind of day we were going to have ... would she be cooperative or obstructive?"[117] He had little patience with her method-acting technique and said that instead of going to the Actors Studio "she should have gone to a train-engineer's school ... to learn something about arriving on schedule."[118] Wilder had become ill during filming, and explained, "We were in mid-flight—and there was a nut on the plane."[119] In hindsight, he discussed Monroe's "certain indefinable magic" and "absolute genius as a comic actress."[117]

By this time, Monroe had only completed one film, Bus Stop, under her four-picture contract with 20th Century Fox. She agreed to appear in Let's Make Love, which was to be directed by George Cukor, but she was not satisfied with the script, and Arthur Miller rewrote it.[120] Gregory Peck was originally cast in the male lead role, but he refused the role after Miller's rewrite; Cary Grant, Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner and Rock Hudson also refused the role before it was offered to Yves Montand.[121] Monroe and Miller befriended Montand and his wife, actress Simone Signoret, and filming progressed well until Miller was required to travel to Europe on business. Monroe began to leave the film set early and on several occasions failed to attend, but her attitude improved after Montand confronted her. Signoret returned to Europe to make a film, and Monroe and Montand began a brief affair that ended when Montand refused to leave Signoret.[122] The film was not a critical or commercial success.[123]

Monroe's health deteriorated during this period, and she began to see a Los Angeles psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson. He later recalled that during this time she frequently complained of insomnia, and told Greenson that she visited several medical doctors to obtain what Greenson considered an excessive variety of drugs. He concluded that she was progressing to the point of addiction, but also noted that she could give up the drugs for extended periods without suffering any withdrawal symptoms.[124] According to Greenson, the marriage between Miller and Monroe was strained; he said that Miller appeared to genuinely care for Monroe and was willing to help her, but that Monroe rebuffed while also expressing resentment towards him for not doing more to help her.[125] Greenson stated that his main objective at the time was to enforce a drastic reduction in Monroe's drug intake.[126]

In 1956, Arthur Miller had briefly resided in Nevada and wrote a short story about some of the local people he had become acquainted with, a divorced woman and some aging cowboys. By 1960 he had developed the short story into a screenplay, and envisaged it as containing a suitable role for Monroe. It became her last completed film, The Misfits, directed by John Huston and starring Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift, Eli Wallach and Thelma Ritter. Shooting commenced in July 1960, with most taking place in the hot Northern Nevada desert.[127] Monroe was frequently ill and unable to perform, and away from the influence of Dr. Greenson, she had resumed her consumption of sleeping pills and alcohol.[126] A visitor to the set, Susan Strasberg, later described Monroe as "mortally injured in some way,"[128] and in August, Monroe was rushed to Los Angeles where she was hospitalized for ten days. Newspapers reported that she had been near death, although the nature of her illness was not disclosed.[129] Louella Parsons wrote in her newspaper column that Monroe was "a very sick girl, much sicker than at first believed", and disclosed that she was being treated by a psychiatrist.[129] Monroe returned to Nevada and completed the film, but she became hostile towards Arthur Miller, and public arguments were reported by the press.[130] Making the film had proved to be an arduous experience for the actors; in addition to Monroe's distress, Montgomery Clift had frequently been unable to perform due to illness, and by the final day of shooting, Thelma Ritter was in hospital suffering from exhaustion. Gable, commenting that he felt unwell, left the set without attending the wrap party.[131] Monroe and Miller returned to New York on separate flights.[132]

Within ten days Monroe had announced her separation from Miller, and Gable had died from a heart attack.[133] Gable's widow, Kay, commented to Louella Parsons that it had been the "eternal waiting" on the set of The Misfits that had contributed to his death, though she did not name Monroe. When reporters asked Monroe if she felt guilty about Gable's death, she refused to answer,[134] but the journalist Sidney Skolsky recalled that privately she expressed regret for her poor treatment of Gable during filming and described her as being in "a dark pit of despair".[135] Monroe later attended the christening of the Gables' son, at the invitation of Kay Gable.[135]

The Misfits received mixed reviews, and was not a commercial success, though some praised the performances of Monroe and Gable.[135] Despite on-set difficulties, Gable, Monroe, and Clift delivered performances that modern movie critics consider superb.[136] Many critics regard Gable's performance to be his finest, and Gable, after seeing the rough cuts, agreed.[137] Monroe received the 1961 Golden Globe Award as "World Film Favorite" in March 1962, five months before her death. Directors Guild of America nominated Huston as best director. The film is now regarded as a classic. Huston later commented that Monroe's performance was not acting in the true sense, and that she had drawn from her own experiences to show herself, rather than a character. "She had no techniques. It was all the truth. It was only Marilyn."[135]

During the following months, Monroe's dependence on alcohol and prescription medications began to take a toll on her health, and friends such as Susan Strasberg later spoke of her illness.[138] Her divorce from Arthur Miller was finalized in January 1961, with Monroe citing "incompatibility of character",[138] and in February she voluntarily entered the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic. Monroe later described the experience as a "nightmare".[139] She was able to phone Joe DiMaggio from the clinic, and he immediately traveled from Florida to New York to facilitate her transfer to the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. She remained there for three weeks. Illness prevented her from working for the remainder of the year; she underwent surgery to correct a blockage in her Fallopian tubes in May, and the following month underwent gallbladder surgery.[140] She returned to California and lived in a rented apartment as she convalesced.

In 1962, Monroe began filming Something's Got to Give, which was to be the third film of her four-film contract with 20th Century Fox. It was to be directed by George Cukor, and co-starred Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse. She was ill with a virus as filming commenced, and suffered from high temperatures and recurrent sinusitis. On one occasion she refused to perform with Martin as he had a cold, and the producer Henry Weinstein recalled seeing her on several occasions being physically ill as she prepared to film her scenes, and attributed it to her dread of performing. He commented, "Very few people experience terror. We all experience anxiety, unhappiness, heartbreaks, but that was sheer primal terror."[141]

On May 19, 1962, she attended the early birthday celebration of President John F. Kennedy at Madison Square Garden, at the suggestion of Kennedy's brother-in-law, actor Peter Lawford. Monroe sang "Happy Birthday" along with a specially written verse based on Bob Hope's "Thanks for the Memory". Kennedy responded to her performance with the remark, "Thank you. I can now retire from politics after having had 'Happy Birthday' sung to me in such a sweet, wholesome way."[142] (also see, Happy Birthday, Mr. President)

Monroe returned to the set of Something's Got to Give and filmed a sequence in which she appeared nude in a swimming pool. Commenting that she wanted to "push Liz Taylor off the magazine covers", she gave permission for several partially nude photographs to be published by Life. Having only reported for work on twelve occasions out of a total of 35 days of production,[141] Monroe was dismissed. The studio 20th Century Fox filed a lawsuit against her for half a million dollars,[143] and the studio's vice president, Peter Levathes, issued a statement saying "The star system has gotten way out of hand. We've let the inmates run the asylum, and they've practically destroyed it."[143] Monroe was replaced by Lee Remick, and when Dean Martin refused to work with any other actress, he was also threatened with a lawsuit.[143] Following her dismissal, Monroe engaged in several high-profile publicity ventures. She gave an interview to Cosmopolitan and was photographed at Peter Lawford's beach house sipping champagne and walking on the beach.[144] She next posed for Bert Stern for Vogue in a series of photographs that included several nudes.[144] Published after her death, they became known as 'The Last Sitting'.

Richard Meryman interviewed her for Life, in which Monroe reflected upon her relationship with her fans and her uncertainties in identifying herself as a "star" and a "sex symbol". She referred to the events surrounding Arthur Miller's appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956, and her studio's warning that she would be "finished" if she showed public support for him, and commented,[145]

You have to start all over again. But I believe you're always as good as your potential. I now live in my work and in a few relationships with the few people I can really count on. Fame will go by, and, so long, I've had you, fame. If it goes by, I've always known it was fickle. So at least it's something I experienced, but that's not where I live.

In the final weeks of her life, Monroe engaged in discussions about future film projects, and firm arrangements were made to continue negotiations on Something's Got to Give.[146] Among the projects was a biography of Jean Harlow filmed two years later unsuccessfully with Carroll Baker. Starring roles in Billy Wilder's Irma la Douce[147] and What a Way to Go! were also discussed; Shirley MacLaine eventually played the roles in both films. Kim Novak replaced her in Kiss Me, Stupid, a comedy in which she was to star opposite Dean Martin. A film version of the Broadway musical, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, and an unnamed World War I-themed musical co-starring Gene Kelly were also discussed, but the projects never materialized due to her death.[146] Her dispute with 20th Century Fox was resolved, her contract was renewed into a $1 million two-picture deal, and filming of Something's Got to Give was scheduled to resume in early fall 1962. Marilyn, having fired her own agent and MCA in 1961, managed her own negotiations as President of Marilyn Monroe Productions. Also on the table was an Italian four-film deal worth 10 million giving her script, director, and co-star approval.[148] Allan "Whitey" Snyder who saw her during the last week of her life, said Monroe was pleased by the opportunities available to her, and that she "never looked better [and] was in great spirits".[146]

Personal life

Monroe had three marriages, all of which ended in divorce. The first, soon after she turned 16, was to James Dougherty, a sheet-metal worker five years her senior. They married in June 1942, six-months after the U.S. entered World War II. He chose to enlist the following year, becoming a Marine trainer, which left Monroe home alone and bored.[149]:21 They divorced after he returned from serving in Asia in 1946. She later blamed her legal guardian, Grace McKee, for encouraging her to marry him while she was still very young.[150]

Her second marriage was to Joe DiMaggio, a retired baseball star with the New York Yankees, and took place on January 14, 1954 in San Francisco. Arguments related to mental cruelty, jealousy and fame ended their marriage later that same year. Monroe later commented: "He was jealous of me because I was more famous than he was. That is what ended our marriage."[151] Other biographers also noted that DiMaggio's jealousy resulted from his possessiveness and his worries about Monroe's possible marital infidelity.[152]

In June 1956 she married playwright and screenwriter Arthur Miller, who would later write two of her film's screenplays. They first met in 1950 during the filming of Bus Stop, and began seeing one another a year after her divorce from DiMaggio. Months later, Miller was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee to explain his supposed communist affiliations. Monroe was urged by studio executives to abandon Miller rather than risk her career, but she refused, calling them "born cowards".[153] When they married, one headline announced, "Egghead Weds Hourglass."[149]:155

Monroe had just turned 30 when they married, and never having a real family of her own, she was eager to join the family of her new husband. Monroe chose to convert to Judaism to "express her loyalty and get close to both Miller and his parents," writes biographer Jeffrey Meyers.[149]:156 Monroe explained to her close friend, Susan Strasberg: "I can identify with the Jews. Everybody's always out to get them, no matter what they do, like me."[149]:156 After she became Jewish, Egypt retaliated by banning all her movies.[149]:157 They divorced five years later after they completed The Misfits (1961), which Miller wrote and Monroe starred in, due to ongoing personality conflicts.

Director Billy Wilder, who described Monroe as "Cinderella without the happy ending," tried to sum up her marriage problems. He directed her in The Seven Year Itch, when she was married to DiMaggio, and in Some Like It Hot, when she was married to Miller:

Her marriages didn't work out because Joe DiMaggio found out she was Marilyn Monroe, and Arthur Miller found out she wasn't Marilyn Monroe.[154]

Monroe's other relationships have garnered much press. The extent of a relationship between President Kennedy and Monroe will never be known, although the White House switchboard did note calls from her during 1962.[155][156] In the opinion of one writer, Monroe was in love with President Kennedy and wanted to marry him, and when their affair ended, she turned to Robert Kennedy, who reportedly visited Monroe in Los Angeles the day that she died.[157]

Monroe had a long experience with psychoanalysis. She was in analysis with Margaret Herz Hohenberg, Anna Freud, Marianne Rie Kris, Ralph Greenson (who found Monroe dead), and Milton Wexler.[158]

Death and aftermath

On August 5, 1962, at 4:25 a.m., LAPD sergeant Jack Clemmons received a call from Dr. Ralph Greenson, Monroe's psychiatrist, saying that Monroe was found dead at her home at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive in Brentwood, Los Angeles, California.[159] She was 36 years old. At the subsequent autopsy, 8 mg/dL of chloral hydrate and 4.5 mg/dL of Nembutal were found in her system,[160] and Dr. Thomas Noguchi (known as the "coroner to the stars") of the Los Angeles County Coroners office recorded cause of death as "acute barbiturate poisoning", resulting from a "probable suicide".[161] Many theories, including murder, circulated about the circumstances of her death and the timeline after the body was found. Some conspiracy theories involved John and Robert Kennedy, while other theories suggested CIA or Mafia complicity. It was reported that President Kennedy was the last person Monroe called.[162][163]

Monroe was interred on August 8, 1962, in a crypt at Corridor of Memories No. 24, at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles. Joe DiMaggio took control of the funeral arrangements, which consisted of only 31 close family and friends, excluding Hollywood's elite. Lee Strasberg, her acting teacher, delivered the eulogy, and had once claimed that of all his acting students, she was the one who stood out above the rest, second only to Marlon Brando. As part of her eulogy, he stated:

In her eyes, and in mine, her career was just beginning.... She had a luminous quality. A combination of wistfulness, radiance, and yearning that set her apart and made everyone wish to be part of it – to share in the childish naivete which was at once so shy and yet so vibrant.[164]

Police were also present to keep the press away.[165] Her casket was silver finished solid bronze and was lined with champagne colored silk.[166] Allan "Whitey" Snyder did her make-up, which was supposedly a promise made in earlier years if she were to die before him.[166] She was wearing her favorite green Emilio Pucci dress.[166] In her hands was a small bouquet of pink teacup roses.[166] For the next 20 years, red roses were placed in a vase attached to the crypt, courtesy of DiMaggio.[165]

In 1992, Playboy magazine founder Hugh Hefner, who never met Monroe, bought the crypt immediately to the left of hers at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery.[167] He was proud of the fact that Monroe had graced the first Playboy centerfold.[168] In August 2009, the crypt space directly above that of Monroe was placed for auction[169] on eBay. Elsie Poncher planned to exhume her husband and move him to an adjacent plot. She advertised the crypt, hoping "to make enough money to pay off the $1.6 million mortgage" on her Beverly Hills mansion.[167] The winning bid was placed by an anonymous Japanese man for $4.6 million,[170] but the winning bidder later backed out "because of the paying problem".

Administration of estate

In her will, Monroe stated she would leave Lee Strasberg her personal effects, which amounted to just over half of her residuary estate, expressing her desire that he "distribute [the effects] among my friends, colleagues and those to whom I am devoted".[171] Instead, Strasberg stored them in a warehouse, and willed them to his widow, Anna, who successfully sued Los Angeles–based Odyssey Auctions in 1994 to prevent the sale of items consigned by the nephew of Monroe's business manager, Inez Melson. In October 1999, Christie's auctioned the bulk of Monroe's effects, including those recovered from Melson's nephew, netting an amount of $13,405,785. Subsequently, Strasberg sued the children of four photographers to determine rights of publicity, which permits the licensing of images of deceased personages for commercial purposes. The decision as to whether Monroe was a resident of California, where she died and where her will was probated,[172] or New York, which she considered her primary residence, was worth millions.[173]

On May 4, 2007, a New York judge ruled that Monroe's rights of publicity ended at her death.[174][175][176] In October 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed Senate Bill 771.[177] The legislation, supported by Anna Strasberg and the Screen Actors Guild, established that non-family members may inherit rights of publicity through the residuary clause of the deceased's will, provided that the person was a resident of California at the time of death.[178][179] In March 2008, the United States District Court in Los Angeles ruled that Monroe was a resident of New York at the time of her death, citing the statement of the executor of her estate to California tax authorities, and a 1966 affidavit by her housekeeper.[180] The decision was reaffirmed by the United States District Court of New York in September 2008.[181]

In July 2010, Monroe's Brentwood home was put up for sale by Prudential California Realty. The house was sold for $3.6 million.[182] Monroe left to Lee Strasberg an archive of her own writing—diaries, poems, and letters, which Anna discovered in October 1999. In October 2010, the documents were published as a book, Fragments (ISBN 0-00-739534-5).[183]

Books

Many books have been written about Marilyn Monroe. A selection is below:

- Marilyn: Her Life in Her Own Words: Marilyn Monroe's Revealing Last Words and Photographs by George Barris (April 1, 2001)

- My Story by Marilyn Monroe and Ben Hecht (September 29, 2006)

- Marilyn in Art by Roger Taylor (May 1, 2006)

- Marilyn Monroe: Metamorphosis by David Wills (November 8, 2011)

Portrayals

Film

Monroe has been portrayed by:

- Misty Rowe in Goodbye Norma Jeane (a highly fictionalized telling of Marilyn's early years) (1976)

- Catherine Hicks in Marilyn: The Untold Story (1980)

- Linda Kerridge plays a Monroe look-alike in the horror film Fade to Black (1980)

- Theresa Russell in Insignificance, where an unnamed Monroe goes to a fictional meeting with Albert Einstein, Joseph McCarthy, and husband Joe DiMaggio (1985)

- Susan Griffiths is a Marilyn Monroe impersonator who has either portrayed Monroe or a look-alike, in the biopic Marilyn & Me (1991), in the 1994 film Pulp Fiction, and in the TV series Quantum Leap, Dark Skies, Curb Your Enthusiasm and Timecop

- Melody Anderson in Marilyn & Bobby: Her Final Affair (1993)

- Ashley Judd as the younger Marilyn, and by Mira Sorvino as the older Marilyn in the film Norma Jean & Marilyn (1996)

- Barbara Niven in The Rat Pack (1998)

- Kerri Randles in Introducing Dorothy Dandridge (1999)

- Poppy Montgomery in Blonde (2001)

- Holly Beavon in James Dean (2001)

- Sophie Monk in The Mystery of Natalie Wood (2004)

- Samantha Morton plays a Marilyn Monroe impersonator in Mister Lonely (2007)

- Michelle Williams in My Week with Marilyn (2011)

Television

Monroe has been portrayed by:

- Constance Forslund in This Year's Blonde (1980)

- Suzie Kennedy impersonated Marilyn Monroe in the episode Who Killed Marilyn Monroe? (2003) of the TV series Revealed and in the Italian movie Io & Marilyn (2009)

- Charlotte Sullivan in The Kennedys (2011)

- Megan Hilty, Uma Thurman and Katharine McPhee play actresses who portray Monroe in the TV series Smash (2012–13).

Theatre

Monroe has been portrayed by:

- Laura Aikin in Robin de Raaff's opera Waiting for Miss Monroe (2012)[184]

- Sunny Thompson in the one woman production Marilyn: Forever Blonde[185]

- Eivør Pálsdóttir in Gavin Bryars' opera Marilyn Forever[186]

Music

Monroe has been portrayed by:

- Lorenzo Ferrero in the opera Marilyn (1980)

- Madonna in the Material Girl music video (1985)

- Mariah Carey in her music video "I Still Believe" (1998)

- Lana del Rey in "National Anthem" (2012)

Tributes

Troy Talton and Donald Kinder wrote a song, entitled "Marilyn", in honor of Marilyn after her death in 1962. It was recorded by Talton and released as a single by Crest Records.[187][188]

Elton John (music) and Bernie Taupin (lyrics) wrote another song in her honor, "Candle in the Wind".[189]

Glenn Danzig of the American rock band The Misfits (who were named after Monroe's final film[190]) released a song named "Who Killed Marilyn?" in 1981.

Filmography

Songs

| Year | Film title | Song title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Ladies of the Chorus | "Every Baby Needs a Da-Da-Daddy" | |

| "Anyone Can See I Love You" | |||

| "Ladies of the Chorus" | |||

| 1950 | A Ticket to Tomahawk | "Oh, What a Forward Young Man You Are" | |

| 1953 | Niagara | "Kiss" | |

| 1953 | Gentlemen Prefer Blondes | "Two Little Girls from Little Rock" | |

| "When Love Goes Wrong" | |||

| "Bye Bye Baby" | |||

| "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend" | |||

| 1953 | Recordings for RCA | "She Acts Like A Woman Should" | |

| "You'd Be Surprised" | |||

| "A Fine Romance" | |||

| "Do It Again" | |||

| 1954 | River of No Return | "I'm Gonna File My Claim" | |

| "One Silver Dollar" | Covered by Vaya Con Dios (album track) | ||

| "Down in the Meadow" | |||

| "River of No Return" | |||

| 1954 | There's No Business Like Show Business | "Heat Wave" | |

| "Lazy" | |||

| "After You Get What You Want" | |||

| "A Man Chases a Girl" | |||

| 1956 | Bus Stop | "That Old Black Magic" | |

| 1957 | The Prince and the Showgirl | "I Found a Dream" | |

| 1959 | Some Like It Hot | "Runnin' Wild" | |

| "I Wanna Be Loved By You" | |||

| "I'm Through With Love" | |||

| "Some Like It Hot" | |||

| 1960 | Let's Make Love | "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" | |

| "Specialization" | |||

| "Let's Make Love" | |||

| "Incurably Romantic" | |||

| 1962 | – | "Happy Birthday, Mr. President" |

"When I Fall In Love"

Contrary to popular belief, Monroe did not ever record the song "When I Fall In Love". The version widely attributed to her and included on many compilation CDs[191] was actually recorded in 1960 by actress Sandra Dee.[192]

Awards and nominations

- 1951 Henrietta Award: The Best Young Box Office Personality

- 1952 Photoplay Award: Fastest Rising Star of 1952

- 1952 Photoplay Award: Special Award

- 1952 Look American Magazine Achievement Award: Most Promising Female Newcomer of 1952

- 1953 Golden Globe Henrietta Award: World Film Favorite Female.

- 1953 Sweetheart of the Month (Playboy)

- 1953 Photoplay Award: Most Popular Female Star

- 1954 Photoplay Award for Best Actress: for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire

- 1956 BAFTA Film Award nomination: Best Foreign Actress for The Seven Year Itch

- 1956 Golden Globe nomination: Best Motion Picture Actress in Comedy or Musical for Bus Stop

- 1958 BAFTA Film Award nomination: Best Foreign Actress for The Prince and the Showgirl

- 1958 David di Donatello Award (Italian): Best Foreign Actress for The Prince and the Showgirl

- 1959 Crystal Star Award (French): Best Foreign Actress for The Prince and the Showgirl

- 1960 Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame 6104 Hollywood Blvd.[193]

- 1960 Golden Globe, Best Motion Picture Actress in Comedy or Musical for Some Like It Hot

- 1962 Golden Globe, World Film Favorite: Female

- 1995 and 2012 (re-dedication) Palm Springs, California, Golden Palm Star – Palm Springs Walk of Stars[194]

- 1999 she was ranked as the sixth greatest female star of all time by the American Film Institute in their list AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars.

See also

- Berniece Baker Miracle, Monroe's half-sister

- Forever Marilyn – a giant statue of Monroe by John Seward Johnson II, now in New Jersey

- Love, Marilyn (2012, biographical documentary film directed by Liz Garbus)

- Marilyn Monroe in popular culture

Notes

- ↑ She obtained an order from the City Court of the State of New York and legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe on February 23, 1956.

- ↑ Tricia Strayer. "Marilyn Monroe's Official Web site .::. Fast Facts". Cmgww.com. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Marilyn Monroe Biography". Biography.com. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ↑ Obituary Variety, August 8, 1962, page 63.

- ↑ "February 20, 2003: IN THE NEWS". North Coast Journal. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ↑ Hall, Susan G. (2006). American Icons: An Encyclopedia of the People, Places, and Things that Have Shaped Our Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-275-98429-8.

- ↑ Rollyson, Carl (2005). Female Icons: Marilyn Monroe to Susan Sontag. iUniverse. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-595-35726-0.

- ↑ Churchwell, Sarah (2005). The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7818-3.

- ↑ "Film's Sexiest Women of All Time". TV Guide Network. 2009.

- ↑ Churchwell, pp. 150–51.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 33.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 151.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Summers, p. 5.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 150, citing previous biographers Anthony Summers, Donald Spoto and Fred Guiles.

- ↑ L.A.County Hall of Records Case No. D-53720, 05MAR1927.

- ↑ AP (February 13, 1981). "Mortensen's Death and documents". New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 154.

- ↑ Taraborrelli JR (2009). The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe. New York: Grand Central Publishing, pp. 35–56.

- ↑ "Milestones". EMQ/Families First. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ↑ Taraborrelli JR (2009). The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe. New York: Grand Central Publishing, pp. 81–83.

- ↑ Daniel Schechter, Erica Willheim (2009). Evaluation of possible child sexual abuse and its sequelae in the case of an adult female patient. In JW Barnhill (Ed.) Approach to the Psychiatric Patient. American Psychiatric Association Press. pp. 328–332.

- ↑ She obtained an order from the City Court of the State of New York and legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe on February 23, 1956.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 McLellan, Dennis (August 18, 2005). "James Dougherty, 84; Was Married to Marilyn Monroe Before She Became a Star". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Personal Letter from a 16-Year Old Marilyn Monroe Sells for $52,460 at Bonhams & Butterfields". artdaily.org. April 20, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, p. 129-30, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ↑ Hurlburt, Roger (January 6, 1991). "Monroe An Exhibit Of The Early Days Of Marilyn Monroe – Before She Became A Legend – Brings The Star`s History In Focus". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ↑ "YANK USA 1945". Wartime Press.Com. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, p. 130, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchen, p. 288.

- ↑ Spoto, Donald (2001). Marilyn Monroe: The Biography. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1183-9., p.115.

- ↑ Summers, p. 27.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Doll, Susan, PhD (n.d.). "Marilyn Monroe's Early Career". HowStuffWorks.com (Planet Green). Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ↑ von Sorge, Helmut (April 30, 1984). "Palm Springs – das Goldene Kaff". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ↑ Summers, p. 38.

- ↑ Summers, p. 43.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Summers, p. 45.

- ↑ Sarah Churchwell (2004). The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe. Henry Holt and Company. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8050-7818-3. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

De Dienes took many of the Monroe's most famous early photographs as 'Norma Jeane,"' including those of her climbing a hillside in khakis and green sweater, and sitting on the highway, as well as the shots on Tobay Beach in August 1949. ... Those pictures of Marilyn in a bathing suit recall the art picture, but they also subvert the pinup, in being far more active, playful, even romping, than the usually static pinup girl.

- ↑ Staggs, p. 92.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 228.

- ↑ Summers, p. 50.

- ↑ Evans, pp. 98–109.

- ↑ Wiley and Bona, p. 208.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Summers, p. 58.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Summers, p. 59.

- ↑ Les Harding (2012). They Knew Marilyn Monroe: Famous Persons in the Life of the Hollywood Icon. McFarland. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7864-9014-1. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Susan Gunelius (2009). Building Brand Value the Playboy Way. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-230-23958-6. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Gordon Jensen (July 2012). Marilyn: A Great Woman's Struggles: Who Killed Her and Why. the Psychiatric Biography. Xlibris Corporation. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-4771-4150-2. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Evans, p. 112.

- ↑ Mary Sims (November 23, 1936). "Marilyn Monroe Photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt". Immortal Marilyn. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Alfred Eisenstaedt". Artscenecal.com. August 15, 1945. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Stars at Home", Life magazine

- ↑ "Life on Both Sides of the Camera" Life magazine

- ↑ "In Eisie's Camera: The most published photographer"Life magazine article about Eisenstaedt, September 16, 1966 pp. 111–118 (includes similar image from session)

- ↑ Evans, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Summers, p. 67.

- ↑ Jewell and Harbin, p. 266.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 93.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 545.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Riese and Hitchens, p. 132.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 336.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Churchwell, p. 233.

- ↑ Summers, p. 74.

- ↑ W., A. (January 22, 1953). "Niagara (1952) Niagara Falls Vies With Marilyn Monroe". The New York Times. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Churchwell, p. 62.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 340.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 234.

- ↑ Summers, p. 71.

- ↑ Russell, p. 137.

- ↑ Russell, p. 138.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 63.

- ↑ "Palmspringslife.com". Palmspringslife.com. January 13, 2009. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 222.

- ↑ Summers, p. 86.

- ↑ "The 2006 Motion Picture Almanac, Top Ten Money Making Stars". Quigley Publishing Company. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ↑ Summers, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 139.

- ↑ Server, p. 249.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Churchwell, p. 65.

- ↑ Summers, p. 92.

- ↑ Summers, pp. 93–95.

- ↑ Summers, p. 96.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 338.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 440.

- ↑ Summers, p. 101.

- ↑ Summers, p. 103.

- ↑ Summers, pp. 103–105.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 129.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Riese and Hitchens, p. 475.

- ↑ Summers, p. 146.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 309.

- ↑ Summers, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ "Milton H Greene — Archives of The World Famous Photographer". Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ↑ "Milton H. Greene, Amy Greene, Marilyn Monroe on Edward R. Murrow's Person to Person — Video". Miltons-marilyn-monroe.com. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ↑ Summers, p. 128.

- ↑ Strasberg, p. 54.

- ↑ Summers, p. 129.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 325.

- ↑ Summers, p. 142.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 124.

- ↑ Summers, p. 130.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 Summers, p. 145.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 275.

- ↑ Summers, p. 151.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 276.

- ↑ Summers, p. 154.

- ↑ Olivier, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Olivier, p. 213.

- ↑ "Marilyn Monroe and Queen Elizabeth II". Womenshistory.about.com. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 261.

- ↑ "Marilyn Monroe Loses Her Baby By Miscarriage". Moberly Monitor-Index, (Moberly, MO), August 2, 1957, p. 6, cols 6–7,

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 262.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 264.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 111

- ↑ Wyatt, Petronella (April 18, 2008). "Tony Curtis on Marilyn Monroe: It was like kissing Hitler!". The Daily Mail (UK). Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 265.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 489.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Summers, p. 178

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 2.

- ↑ Summers, p. 177.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 269.

- ↑ Summers, p. 183.

- ↑ Summers, p. 186.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 270.

- ↑ Summers, p. 188.

- ↑ Summers, p.189

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Summers, p. 190.

- ↑ Rocha, Guy. "Myth #60 — Myths and "The Misfits"". Retrieved April 17, 2010Sierra Sage, Carson City/Carson Valley, Nevada, January 2001 edition

- ↑ Strasberg, p. 134.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Summers, p. 194.

- ↑ Summers, pp. 192 & 194.

- ↑ Goode, p. 284.

- ↑ Summers, p. 195.

- ↑ Goode, pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Harris, p. 379.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 135.2 135.3 Summers, p. 196.

- ↑ "The Misfits – Movie Reviews, Trailers, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ↑ Miller, Arthur (1987). Timebends. New York: Grove Press. p. 485. ISBN 0-8021-0015-5.

- ↑ 138.0 138.1 Summers, p. 198.

- ↑ Summers, p. 199.

- ↑ Summers, p. 202.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 Summers, p. 268

- ↑ Summers, p. 271.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 143.2 Summers, p. 274.

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 Summers, p. 275.

- ↑ Richard, Meryman (September 14, 1997). "Great interviews of the 20th century: Marilyn Monroe interviewed by Richard Meryman (excerpts of the original interview published by Life Magazine, August 7, 1962)". The Guardian (London). Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 146.2 Summers, p. 301.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 552.

- ↑ Riese and Hitchens, p. 491.

- ↑ 149.0 149.1 149.2 149.3 149.4 Meyers, Jeffrey. The Genius and the Goddess, Univ. of Illinois Press (2009)

- ↑ Monroe, Marilyn. My Story, Cooper Square Press. ISBN 1-58979-316-1.

- ↑ Allen, Howard G. Marilyn Monroe Her Shoe and Me, Xlibris Corp. (2010) e-book

- ↑ Churchwell, p. 232

- ↑ Summers. p.157

- ↑ Chandler, Charlotte. Nobody's Perfect: Billy Wilder, a Personal Biography, Applause Theatre & Cinema Books (2002) pp. 9-10

- ↑ Leaming, Barbara (2006). Jack Kennedy: The Education of a Statesman. pp. 379–380. ISBN 978-0-393051-61-2.

- ↑ Dallek, Robert (2003). An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917–1963. p. 581. ISBN 978-0-316-17238-7.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony (1993). Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover. ISBN 0-575-04236-2.

- ↑ Mecacci, Luciano (2009). Freudian Slips: The Casualties of Psychoanalysis from the Wolf Man to Marilyn Monroe (pp. 1–36, 181–183). Vagabondd Voices, Sulaisiadar 'san Rudha (Scotland). ISBN 978-0-9560560-1-6.

- ↑ Wolfe, Donald H. The Last Days of Marilyn Monroe. (1998) ISBN 0-7871-1807-9.

- ↑ Clayton, p. 361.

- ↑ Summers, pp. 319–320.

- ↑ Reed, Jonathan M. & Squire, Larry R. The Journal of Neuroscience, May 15, 1998, 18(10):3943–3954.

- ↑ Laurence Leamer (October 15, 2002). The Kennedy Men: 1901-1963. HarperCollins. p. 605. ISBN 978-0-06-050288-1. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ↑ Marilyn Monroe's funeral video clip on YouTube, narrated by director John Huston

- ↑ 165.0 165.1 Frank Wilkins. "The Death of Marilyn Monroe". Reel Reviews.

- ↑ 166.0 166.1 166.2 166.3 "Marilyn's Funeral". marilynmonroe.ca.

- ↑ 167.0 167.1 "Monroe 'burial plot' up for sale". BBC News. August 16, 2009. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ↑ Los Angeles Magazine, December 2002, page 30

- ↑ "eBay: Crypt Above Marilyn Monroe For Sale". eBay. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ↑ Dillon, Nancy (August 24, 2009). "Winning bid for tomb above Marilyn Monroe at $4.6 million". Daily News (New York). Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ↑ "The Will of Marilyn Monroe". Court TV. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Clip of December 24, 1962 announcement in Los Angeles Metropolitan News-Enterprise of January 17, 1963 Hearing of Petition for the Probate in the Matter of the Estate of Marilyn Monroe" www.cursumperficio.net July 9, 2010

- ↑ Koppel, Nathan (April 10, 2006). "A battle erupts over the right to market Monroe". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Judge rejects Monroe claim to photographer profits". ABC News. May 5, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Photographer's Heirs Prevail in Dispute over Marilyn Monroe Images, et al". Thearchivesstore.com. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ↑ Hoskins, Michael W. (March 19, 2008). "Indy firm loses Marilyn Monroe rights case". cms.ibj.com. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- ↑ info.sen.ca.gov SB 771. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ↑ Screen Actors Guild on SB 771. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Long-Dead Celebrities Can Now Breathe Easier". The New York Times, October 24, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Marilyn Monroe Estate Takes a Hit" The Wall Street Journal, April 1, 2008. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Indiana Company Loses Marilyn Monroe Lawsuit". Inside Indiana Business, September 4, 2008. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Celebrity Real Estate — Marilyn Monroe Home (Photos) for Sale in Brentwood". National Ledger. July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ↑ Kashner, Sam (November 2010). "Marilyn and Her Monsters". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ↑ Shirley Apthorp (2012-06-12). "Waiting for Miss Monroe, Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam". Financial Times. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ November-18-Following-A-UK-Tour-20090817 "'MARILYN: FOREVER BLONDE' Will Play Leicester Square Theatre October 20 – November 18 Following A UK Tour". Broadwayworld.com. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ↑ Kevin Bazzana (2013-09-15). "Thread of melancholy runs through Marilyn Monroe opera". Times Colonist. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ "1113 TROY TALTON". Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ↑ "Record Details". 45cat.com. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Candle in the Wind by Elton John | Song Stories". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- ↑ Dome, Malcolm (2011). "The Story Behind...Danzig". Metal Hammer (Future plc) (May 2011): 70–72.

- ↑ "Marilyn Monroe – When I Fall in Love". Last.fm.

- ↑ "Songs Marilyn Never Sang". marilynmonroe.ca.

- ↑ Hollywood Walk of Fame Marilyn Monroe dedicated February 8, 1960

- ↑ Golden Palm Star dedicated on December 1, 1995 Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated

References

- Churchwell, Sarah (2004). The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-7818-5.

- Clayton, Marie (2004). Marilyn Monroe: Unseen Archives. Barnes & Noble Inc. ISBN 0-7607-4673-7.

- Evans, Mike (2004). Marilyn: The Ultimate Book. MQ Publications. ASIN B000FL52LG.

- Kouvaros, George. ""The Misfits": What Happened Around the Camera". Film Quarterly (University of California Press) 55 (4): 28–33. doi:10.1525/fq.2002.55.4.28. JSTOR 1213933.

- Gilmore, John (2007). Inside Marilyn Monroe, A Memoir. Ferine Books, Los Angeles. ISBN 0-9788968-0-7.

- Goode, James (1986). The Making of "The Misfits". Limelight Editions, New York. ISBN 0-87910-065-6.

- Guiles, Fred Lawrence (1993). Norma Jean: The Life of Marilyn Monroe. Paragon House Publishers. ISBN 1-55778-583-X.

- Harris, Warren G. (2002). Clark Gable, A Biography. Aurum Press, London. ISBN 1-85410-904-9.

- Jacke, Andreas: Marilyn Monroe und die Psychoanalyse. Psychosozial Verlag, Gießen 2005, ISBN 978-3-89806-398-2, ISBN 3-89806-398-4

- Jewell, Richard B.; Harbin, Vernon (1982). The RKO Story. Octopus Books, London. ISBN 0-7064-1285-0.

- Meaker, M. J. Sudden Endings: 13 Profiles in Depth of Famous Suicides Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, NY: 1964 p. 26–45: "Marilyn and Norma Jean: Marilyn Monroe"

- Mecacci, Luciano (2009). Freudian Slips: The Casualties of Psychoanalysis from the Wolf Man to Marilyn Monroe. Vagabondd Voices, Sulaisiadar 'san Rudha (Scotland). ISBN 978-0-9560560-1-6.

- Monroe, Marilyn; Hecht, Ben (2000). My Story. Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1102-2. Retrieved August 5, 2008.