Marginal product of labor

In economics, the marginal product of labor (MPL) is the change in output that results from employing an added unit of labor.[1]

Definition

The marginal product of a factor of production is generally defined as the change in output associated with a change in that factor, holding other inputs into production constant.

The marginal product of labor is then the change in output (Y) per unit change in labor (L). In discrete terms the marginal product of labor is:

In continuous terms, the MPL is the first derivative of the production function:

Graphically, the MPL is the slope of the production function.

Examples

There is a factory which produces toys. When there are no workers in the factory, no toys are produced. When there is one worker in the factory, six toys are produced per hour. When there are two workers in the factory, eleven toys are produced per hour. There is a marginal product of labor of five when there are two workers in the factory compared to one. When the marginal product of labor is increasing, this is called increasing marginal returns. However, as the number of workers increases, the marginal product of labor may not increase indefinitely. When not scaled properly, the marginal product of labor may go down when the number of employees goes up, creating a situation known as diminishing marginal returns. When the marginal product of labor becomes negative, it is known as negative marginal returns.

Marginal costs

The marginal product of labor is directly related to costs of production. Costs are divided between fixed and variable costs. Fixed costs are costs that relate to the fixed input, capital, or rK, where r is the rate of return and K is the quantity of capital. Variable costs (VC) are the costs of the variable input, labor, or wL, where w is the wage rate and L is the amount of labor employed. Thus, VC = wL . Marginal costs (MC) is the change in total cost per unit change in output or ∆C/∆Q. In the short run, production can be varied only by changing the variable input. Thus only variable costs change as output increases ∆C = ∆VC = ∆Lw. Marginal costs is ∆Lw/∆Q. Now, ∆L/∆Q is the reciprocal of the marginal product of labor (∆Q/∆L). Therefore, marginal cost is simply the wage rate w divided by the marginal product of labor

- MC = ∆VC∕∆q;

- ∆VC = w∆L;

- ∆L∕∆q the change in quantity of labor to affect a one unit change in output = 1∕MPL.

- Therefore MC = w ∕ MPL

Thus if the marginal product of labor is rising then marginal costs will be falling and if the marginal product of labor is falling marginal costs will be rising (assuming a constant wage rate).[3]

Relation between MPL and APL

The average product of labor is the total product of labor divided by the number of units of labor employed, or Q/L.[2] The average product of labor is a common measure of labor productivity.[4][5] The APL curve is shaped like an inverted “u”. At low production levels the APL tends to increases as additional labor is added. The primary reason for the increase is specialization and division of labor.[6] At the point the APL reaches its maximum value APL equals the MPL.[7] Beyond this point the APL falls.

During the early stages of production MPL is greater than APL. When the MPL is above the APL the APL will increase. Eventually the MPL reaches it maximum value at the point of diminishing returns. Beyond this point MPL will decrease. However, at the point of diminishing returns the MPL is still above the APL and APL will continue to increase until MPL equals APL. When MPL is below APL, APL will decrease.

Graphically, the APL curve can be derived from the total product curve by drawing secants from the origin that intersect (cut) the total product curve. The slope of the secant line equals the average product of labor, where the slope = dQ/dL.[6] The slope of the curve at each intersection marks a point on the average product curve. The slope increases until the line reaches a point of tangency with the total product curve. This point marks the maximum average product of labor. It also marks the point where MPL (which is the slope of the total product curve)[8] equals the APL (the slope of the secant).[9] Beyond this point the slope of the secants become progressively smaller as APL declines. The MPL curve intersects the APL curve from above at the maximum point of the APL curve. Thereafter, the MPL curve is below the APL curve.

Diminishing marginal returns

The falling MPL is due to the law of diminishing marginal returns. The law states, ”as units of one input are added (with all other inputs held constant) a point will be reached where the resulting additions to output will begin to decrease; that is marginal product will decline”.[10] The law of diminishing marginal returns applies regardless of whether the production function exhibits increasing, decreasing or constant returns to scale. The key factor is that the variable input is being changed while all other factors of production are being held constant. Under such circumstances diminishing marginal returns are inevitable at some level of production.[11]

Diminishing marginal returns differs from diminishing returns. Diminishing marginal returns means that the marginal product of the variable input is falling. Diminishing returns occur when the marginal product of the variable input is negative. That is when a unit increase in the variable input causes total product to fall. At the point that diminishing returns begin the MPL is zero.[12]

MPL, MRPL and profit maximization

The general rule is that a firm maximizes profit by producing that quantity of output where marginal revenue equals marginal costs. The profit maximization issue can also be approached from the input side. That is, what is the profit maximizing usage of the variable input? To maximize profits the firm should increase usage "up to the point where the input’s marginal revenue product equals its marginal costs". So, mathematically the profit maximizing rule is MRPL = MCL.[10] The marginal profit per unit of labor equals the marginal revenue product of labor minus the marginal cost of labor or MπL = MRPL − MCLA firm maximizes profits where MπL = 0.

The marginal revenue product is the change in total revenue per unit change in the variable input assume labor.[10] That is, MRPL = ∆TR/∆L. MRPL is the product of marginal revenue and the marginal product of labor or MRPL = MR × MPL.

- Derivation:

- MR = ∆TR/∆Q

- MPL = ∆Q/∆L

- MRPL = MR × MPL = (∆TR/∆Q) × (∆Q/∆L) = ∆TR/∆L

Example

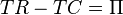

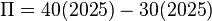

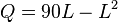

- Assume that the production function is

[10]

[10]

•

• Output price is $40 per unit.

(Profit Max Rule)

(Profit Max Rule)

- 44.625 is the profit maximizing number of workers.

- Thus, the profit maximizing output is 2025 units

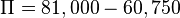

• And the profit is

- Some might be confused by the fact that

as intuition would say that labor should be discrete. Remember, however, that labor is actually a time measure as well. Thus, it can be thought of as a worker not working the entire hour.

as intuition would say that labor should be discrete. Remember, however, that labor is actually a time measure as well. Thus, it can be thought of as a worker not working the entire hour.

Marginal productivity ethics

In the aftermath of the marginal revolution in economics, a number of economists including John Bates Clark and Thomas Nixon Carver sought to derive an ethical theory of income distribution based on the idea that workers were morally entitled to receive a wage exactly equal to their marginal product. In the 20th century, marginal productivity ethics found few supporters among economists, being criticised not only by egalitarians but by economists associated with the Chicago school such as Frank Knight (in The Ethics of Competition) and the Austrian School, such as Leland Yeager.[13] However, marginal productivity ethics were defended by George Stigler.

Footnotes

- ↑ Sullivan, Arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 108. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Perloff, J., Microeconomics Theory and Applications with Calculus, Pearson 2008. p. 173.

- ↑ Pindyck, R. and D. Rubinfeld, Microeconomics, 5th ed. Prentice-Hall 2001.

- ↑ Nicholson, W. and C. Snyder, Intermediate Microeconomics, Thomson 2007, p. 215.

- ↑ Nicholson, W., Microeconomic Theory, 9th ed. Thomson 2005, p. 185.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Perloff, J., Microeconomics Theory and Applications with Calculus, Pearson 2008, p. 176.

- ↑ Binger, B. and E. Hoffman, Microeconomics with Calculus, 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley 1998, p. 253.

- ↑ Krugman, Paul; Robin Wells (2010). Microeconomics. Worth Publishers. p. 306. ISBN 978-1429277914.

- ↑ Perloff, J: Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus page 177. Pearson 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Samuelson, W. and S. Marks, Managerial Economics, 4th ed. Wiley 2003, p. 227.

- ↑ Hal Varian, Microeconomic Analysis, 3rd ed. Norton 1992.

- ↑ Perloff, J., Microeconomics Theory and Applications with Calculus, Pearson 2008, p. 178.

- ↑ "Can a Liberal Be an Equalitarian? Leland B. Yeager - Toward Liberty: Essays in Honor of Ludwig von Mises, vol. 2". Online Library of Liberty. 1971-09-29. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

References

- Binger, B. and E. Hoffman, Microeconomics with Calculus, 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley 1998, ISBN 0-321-01225-9

- Krugman, Paul, and Robin Wells (2009), Microeconomics 2d ed. Worth Publishers, ISBN 978-1429277914

- Nicholson, W., Microeconomic Theory, 9th ed. Thomson 2005.

- Nicholson, W. and C. Snyder, Intermediate Microeconomics, Thomson 2007, ISBN 0-324-31968-1

- Perloff, J., Microeconomics Theory and Applications with Calculus, Pearson 2008, ISBN 978-0-321-27794-7

- Pindyck, R. and D. Rubinfeld, Microeconomics, 5th ed. Prentice-Hall 2001. ISBN 0-13-019673-8

- Samuelson, W. and S. Marks, Managerial Economics, 4th ed. Wiley 2003.

- Varian, Hal, Microeconomic Analysis, 3rd ed. Norton 1992.