Margaret Hamilton (scientist)

| Margaret Hamilton | |

|---|---|

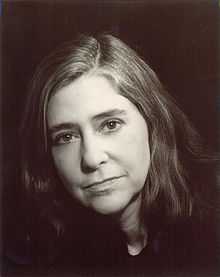

Hamilton in 1995 | |

| Born |

August 17, 1936 Paoli, Indiana |

| Education |

University of Michigan Earlham College |

| Occupation |

CEO of Hamilton Technologies, Inc. Computer scientist |

| Spouse(s) | James Cox Hamilton |

Margaret Heafield Hamilton (born August 17, 1936)[1] is a computer scientist, systems engineer, and business owner. She was Director of the Software Engineering Division of the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, which developed on-board flight software for the Apollo space program.[2] Hamilton's team's work prevented an abort of the Apollo 11 moon landing.[3] In 1986, she became the founder and CEO of Hamilton Technologies, Inc. in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The company was developed around the Universal Systems Language based on her paradigm of Development Before the Fact (DBTF) for systems and software design.[4]

Hamilton has published over 130 papers, proceedings, and reports concerned with the 60 projects and six major programs in which she has been involved.

Early life

Margaret Heafield was born to Kenneth Heafield and Ruth Esther Heafield (née Partington).[5] She graduated from Hancock High School in 1954, majored in mathematics at the University of Michigan and earned a B.A. in mathematics with a minor in philosophy from Earlham College in 1958.[6] After graduation, she briefly taught high school math and French while her husband finished earning his undergraduate degree. She moved to Boston, Massachusetts, with the intention of doing graduate study in abstract mathematics at Brandeis University. In 1960 she took an interim position at MIT to develop software for predicting weather on the LGP-30 and the PDP-1 computers (at Marvin Minsky's Project MAC) for professor Edward Norton Lorenz in the meteorology department.[1][7] At that time, computer science and software engineering were not yet disciplines; instead, programmers learned on the job with hands-on experience.[2]

From 1961 to 1963, she worked on the SAGE Project at Lincoln Labs where she wrote software for the first AN/FSQ-7 computer (the XD-1 computer) to search for "unfriendly" aircraft; she also wrote software for the Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories.

NASA

Hamilton then joined the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory at MIT, which at the time was working on the Apollo space mission. She became the director and supervisor of software programming[8] in 1965.

At NASA, Hamilton's team was responsible for helping pioneer the Apollo on-board guidance software required to navigate and land on the Moon, and its multiple variations used on numerous missions (including the subsequent Skylab).[2] She worked to gain hands-on experience during a time when computer science and software engineering courses or disciplines were non-existent.

Her areas of expertise include system design and software development, enterprise and process modelling, development paradigm, formal systems modelling languages, system-oriented objects for systems modelling and development, automated life-cycle environments, methods for maximizing software reliability and reuse, domain analysis, correctness by built-in language properties, open-architecture techniques for robust systems, full life-cycle automation, quality assurance, seamless integration, error detection and recovery techniques, man/machine interface systems, operating systems, end-to-end testing techniques, and life-cycle management techniques.[2]

She developed concepts of asynchronous software, priority scheduling, and Human-in-the-loop decision capability, which became the foundation for modern, ultra-reliable software design.

Apollo 11

Hamilton's work prevented an abort of the Apollo 11 Moon landing:[3] Three minutes before the Lunar lander reached the Moon's surface, several computer alarms were triggered. The computer was overloaded with incoming data, because the rendezvous radar system (not necessary for landing) updated an involuntary counter in the computer, which stole cycles from the computer. Due to its robust architecture, the computer was able to keep running; the Apollo onboard flight software was developed using an asynchronous executive so that higher priority jobs (important for landing) could interrupt lower priority jobs. The fault was attributed to a faulty checklist and the radar being erroneously activated by the crew.

Due to an error in the checklist manual, the rendezvous radar switch was placed in the wrong position. This caused it to send erroneous signals to the computer. The result was that the computer was being asked to perform all of its normal functions for landing while receiving an extra load of spurious data which used up 15% of its time. The computer (or rather the software in it) was smart enough to recognize that it was being asked to perform more tasks than it should be performing. It then sent out an alarm, which meant to the astronaut, I'm overloaded with more tasks than I should be doing at this time and I'm going to keep only the more important tasks; i.e., the ones needed for landing ... Actually, the computer was programmed to do more than recognize error conditions. A complete set of recovery programs was incorporated into the software. The software's action, in this case, was to eliminate lower priority tasks and re-establish the more important ones ... If the computer hadn't recognized this problem and taken recovery action, I doubt if Apollo 11 would have been the successful moon landing it was.—Margaret Hamilton, Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming MIT Draper Laboratory, Cambridge, Massachusetts, "Computer Got Loaded", Letter to Datamation, March 1, 1971[9]

Businesses

Hamilton was the CEO from 1976 through 1984 of a company she co-founded called Higher Order Software (HOS) that created a product called USE.IT, based on the HOS methodology.[10][11][12]

In 1986, she became the founder and CEO of Hamilton Technologies, Inc. in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The company was developed around the Universal Systems Language (USL) and its associated automated environment, the 001 Tool Suite, based on her paradigm of Development Before The Fact (DBTF) for systems design and software development.[4][13][14][15]

Legacy

Hamilton is credited with coining the term "software engineering".[16] In this field she was one of those who developed the concepts of asynchronous software, priority scheduling, end-to-end testing, and human-in-the-loop decision capability, such as priority displays which then became the foundation for ultra reliable software design.[17]

Awards

- 1986, Augusta Ada Lovelace Award, Association for Women in Computing.[6]

- 2003, NASA Exceptional Space Act Award for scientific and technical contributions. The award included $37,200, the largest amount awarded to any individual in NASA's history.[3][17][18]

- 2009, Outstanding Alumni Award, Earlham College.[6]

Personal life

She met her husband James Cox Hamilton while at Earlham College. They married in the late 1950s after Heafield earned her bachelor's degree. They had a daughter together named Lauren. The couple eventually divorced.[19]

Publications

- M. Hamilton (1994), "Inside Development Before the Fact," cover story, Special Editorial Supplement, 8ES-24ES. Electronic Design, Apr. 1994.

- M. Hamilton (1994), "001: A Full Life Cycle Systems Engineering and Software Development Environment," cover story, Special Editorial Supplement, 22ES-30ES. Electronic Design, Jun. 1994.

- M. Hamilton, Hackler, W. R.. (2004), Deeply Integrated Guidance Navigation Unit (DI-GNU) Common Software Architecture Principles (revised dec-29-04), DAAAE30-02-D-1020 and DAAB07-98-D-H502/0180, Picatinny Arsenal, NJ, 2003-2004.

- M. Hamilton and W. R. Hackler (2007), "Universal Systems Language for Preventative Systems Engineering," Proc. 5th Ann. Conf. Systems Eng. Res. (CSER), Stevens Institute of Technology, Mar. 2007, paper #36.

- M. Hamilton and W. R. Hackler (2007), "A Formal Universal Systems Semantics for SysML", 17th Annual International Symposium, INCOSE 2007, San Diego, CA, Jun. 2007.

- M. Hamilton and W. R. Hackler (2008), "Universal Systems Language: Lessons Learned from Apollo", IEEE Computer, Dec. 2008.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tiffany K. Wayne (2011). American Women of Science Since 1900. ABC-CLIO. pp. 480–1. ISBN 978-1-59884-158-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 NASA Office of Logic Design "About Margaret Hamilton" (Last Revised: February 03, 2010)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Michael Braukus NASA News "NASA Honors Apollo Engineer" (Sept. 3, 2003)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 M. Hamilton, W.R. Hackler (December 2008). "Universal Systems Language: Lessons Learned from Apollo". IEEE Computer. doi:10.1109/MC.2008.541.

- ↑ "Ruth Esther Heafield". Wujek-Calcaterra & Sons. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "2009 Outstanding Alumni and Distinguished Service Awards". Earlham College. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ↑ Steven Levy (1984), Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19195-2

- ↑ "Margaret Hamilton". Cambridge Women's Heritage Project. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Hamilton, Margaret H. (March 1, 1971). "Computer Got Loaded". Datamation (Letter) (Cahners Publishing Company). ISSN 0011-6963.

- ↑ M. Hamilton, S. Zeldin (1976) "Higher order software—A methodology for defining software" IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. SE-2, no. 1, Mar. 1976.

- ↑ Thompson, Arthur A.; Strickland, A. J., (1996), "Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases", McGraw-Hill Companies, ISBN=0-256-16205-0

- ↑ Rowena Barrett (1 June 2004). Management, Labour Process and Software Development: Reality Bites. Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-134-36117-5.

- ↑ Krut, Jr., B., (1993) “Integrating 001 Tool Support in the Feature-Oriented Domain Analysis Methodology” (CMU/SEI-93-TR-11, ESC-TR-93-188), Pittsburgh, SEI, Carnegie Mellon University.

- ↑ Ouyang, M., Golay, M.W. (1995), An Integrated Formal Approach for Developing High Quality Software of Safety-Critical Systems, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, Report No. MIT-ANP-TR-035.

- ↑ Software Productivity Consortium, (SPC) (December 1998), Object-Oriented Methods and Tools Survey, Herndon, VA.SPC-98022-MC, Version 02.00.02.

- ↑ Rayl, A.J.S. (October 16, 2008). "NASA Engineers and Scientists-Transforming Dreams Into Reality". http://www.nasa.gov/index.html''. NASA. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 NASA Press Release "NASA Honors Apollo Engineer" (September 03, 2003)

- ↑ NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe has commented saying "The concepts she and her team created became the building blocks for modern software engineering. It's an honor to recognize Ms. Hamilton for her extraordinary contributions to NASA.".

- ↑ Stickgold, Emma (August 31, 2014). "James Cox Hamilton, at 77; lawyer was quiet warrior for First Amendment". Boston Globe. Retrieved December 15, 2014.