Mare Boreum quadrangle

|

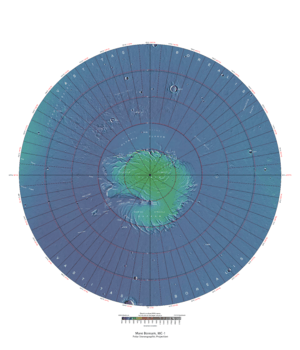

Map of Mare Boreum quadrangle from Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) data. The highest elevations are red and the lowest are blue. | |

| Coordinates | 75°N 0°W / 75°N -0°ECoordinates: 75°N 0°W / 75°N -0°E |

|---|---|

The Mare Boreum quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Mare Boreum quadrangle is also referred to as MC-1 (Mars Chart-1).[1] Its name derives from an older name for a feature that is now called Planum Boreum, a large plain surrounding the polar cap.[2]

The quadrangle covers all of the Martian surface north of latitude 65°. It includes the north polar ice cap, which has a swirl pattern and is roughly 1,100 km across. Mariner 9 in 1972 discovered a belt of sand dunes that ring the polar ice deposits, which is 500 km across in some places and may be the largest dune field in the solar system.[3] The ice cap is surrounded by the vast plains of Planum Boreum and Vastitas Borealis. Close to the pole, there is a large valley, Chasma Boreale, that may have been formed from water melting from the ice cap.[4] An alternative view is that it was made by winds coming off the cold pole.[5][6] Another prominent feature is a smooth rise, called Olympia Planitia. In the summer, a dark collar around the residual cap becomes visible; it is mostly caused by dunes.[7] The quadrangle includes some very large craters that stand out in the north because the area is smooth with little change in topography. These large craters are Lomonosov and Korolev. Although smaller, the crater Stokes is also prominent.

The Phoenix lander landed on Vastitas Borealis within the Mare Boreum quadrangle at 68.218830° N and 234.250778° E on May 25, 2008.[8] The probe collected and analyzed soil samples in an effort to detect water and determine how hospitable the planet might once have been for life to grow. It remained active there until winter conditions became too harsh around five months later.[9]

After the mission ended the journal Science reported that chloride, bicarbonate, magnesium, sodium potassium, calcium, and possibly sulfate were detected in the samples analyzed by Phoenix. The pH was narrowed down to 7.7±0.5. Perchlorate (ClO4), a strong oxidizer at elevated temperatures, was detected. This was a significant discovery because the chemical has the potential of being used for rocket fuel and as a source of oxygen for future colonists. Also, under certain conditions perchlorate can inhibit life; however some microorganisms obtain energy from the substance (by anaerobic reduction). The chemical when mixed with water can greatly lower freezing points, in a manner similar to how salt is applied to roads to melt ice. So, perchlorate may be allowing small amounts of liquid water to form on Mars today. Gullies, which are common in certain areas of Mars, may have formed from perchlorate melting ice and causing water to erode soil on steep slopes.[10]

Proof for ocean

Strong evidence for a one time ancient ocean was found in Mare Boreum near the north pole (as well as the south pole). In March 2015, a team of scientists published results showing that this region was highly enriched with deuterium, heavy hydrogen, by seven times as much as the Earth. This means that Mars has lost a volume of water 6.5 times what is stored in today's polar caps. The water for a time would have formed an ocean in the low-lying Mare Boreum. The amount of water could have covered the planet about 140 meters, but was probably in an ocean that in places would be almost 1 mile deep.

This international team used ESO’s Very Large Telescope, along with instruments at the W. M. Keck Observatory and the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, to map out different forms of water in Mars’s atmosphere over a six-year period.[11] [12]

See also

- Climate of Mars

- Impact crater

- List of quadrangles on Mars

- Patterned ground

- Phoenix Spacecraft

- Martian polar ice caps

- Vastitas Borealis

- Water on Mars

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mare Boreum quadrangle. |

- ↑ Davies, M.E.; Batson, R.M.; Wu, S.S.C. “Geodesy and Cartography” in Kieffer, H.H.; Jakosky, B.M.; Snyder, C.W.; Matthews, M.S., Eds. Mars. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 1992.

- ↑ Patrick Moore and Robin Rees, ed. Patrick Moore's Data Book of Astronomy (Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 130.

- ↑ Hartmann, W. 2003. A Traveler's Guide to Mars. Workman Publishing. NY NY.

- ↑ Clifford, S. 1987. Polar basal melting on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 92: 9135-9152.

- ↑ Howard, A. 2000. The role of eolian processes in forming surface features of the martian polar layered deposits. Icarus. 144: 267-288.

- ↑ Edgett, K. et al. 2003. Mars landscape evolution: influence of stratigraphy on geomorphology of the north polar region. Geomorphology. 52: 289-298.

- ↑ Michael H. Carr (2006). The surface of Mars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87201-0. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, Emily (2008-05-27). "Phoenix Sol 2 press conference, in a nutshell". The Planetary Society weblog. Planetary Society. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ↑ "Mars lander aims for touchdown in 'Green Valley'". New Scientist Space. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ Hecht, M. et al. 2009. Detection of Perchlorate and the Soluble Chemistry of Martian Soil at the Phoenix Lander Site. Science: 325. 64–67

- ↑ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150305140447.htm

- ↑ . Villanueva, L., Mumma, R. Novak, H. Käufl, P. Hartogh, T. Encrenaz, A. Tokunaga, A. Khayat, M. Smith. Strong water isotopic anomalies in the martian atmosphere: Probing current and ancient reservoirs. Science, 2015 DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa3630

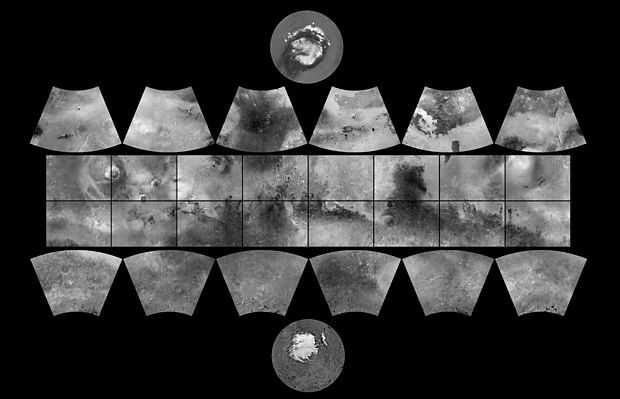

| Quadrangles on Mars | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC-01 Mare Boreum (features) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| MC-05 Ismenius Lacus (features) |

MC-06 Casius (features) |

MC-07 Cebrenia (features) |

MC-02 Diacria (features) |

MC-03 Arcadia (features) |

MC-04 Acidalium (features) | ||||||||||||||||||

| MC-12 Arabia (features) |

MC-13 Syrtis Major (features) |

MC-14 Amenthes (features) |

MC-15 Elysium (features) |

MC-08 Amazonis (features) |

MC-09 Tharsis (features) |

MC-10 Lunae Palus (features) |

MC-11 Oxia Palus (features) | ||||||||||||||||

| MC-20 Sinus Sabaeus (features) |

MC-21 Iapygia (features) |

MC-22 Mare Tyrrhenum (features) |

MC-23 Aeolis (features) |

MC-16 Memnonia (features) |

MC-17 Phoenicis Lacus (features) |

MC-18 Coprates (features) |

MC-19 Margaritifer Sinus (features) | ||||||||||||||||

| MC-27 Noachis (features) |

MC-28 Hellas (features) |

MC-29 Eridania (features) |

MC-24 Phaethontis (features) |

MC-25 Thaumasia (features) |

MC-26 Argyre (features) | ||||||||||||||||||

| MC-30 Mare Australe (features) | |||||||||||||||||||||||