María Rosa Urraca Pastor

| María Rosa Urraca Pastor | |

|---|---|

| Born |

María Rosa Urraca Pastor 1900 Madrid, Spain |

| Died |

1984 Barcelona, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Ethnicity | Spanish |

| Occupation | teacher |

| Known for | orator, propagandist, politician, nurse |

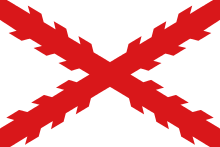

Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista, Falange Española Tradicionalista |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

María Rosa Urraca Pastor (Madrid, 1900 – Barcelona, 1984) was a Spanish Carlist politician and propagandist.

Family and youth

.jpg)

María Rosa Urraca Pastor was born to a profoundly Catholic and religious family. Her father, Juan Urraca Sáenz, originated from Madrid. As a military he served in the Spanish combat units and suffered the POW fate. Married to Rafaela Pastor Ortega, he was transferred to Cuerpo Auxiliar de Intervención Militar and assigned first to Burgos and then to Comisaría de Guerra de Bilbao, where he reached the rank of auxiliar mayor. As a member of numerous religious societies like Hermandad de Nuestra Señora de Valvanera, he passed the pious zeal to the daughter. María Rosa has never married and had no children.

Urraca followed her father's professional lot and as a child moved to Burgos and then to Bilbao. It is there she completed a teacher's college and graduated in 1923, though she pursued her education studying Filosofía y Letras later on. Urraca commenced her professional career by teaching at La Obra del Ave-María, a network of Catholic schools founded by Andrés Manjón and focused on poverty-stricken children.

In the mid-1920s she entered the Biscay section of Acción Católica de la Mujer (to grow into president of the Bilbao section) and got enthusiastically involved in a number of social Roman Catholic educational initiatives, at that time very much encouraged by the Primo de Rivera dictatorship. She became a role model for a new breed of Catholic female public activist, as opposed to the old-style Catholic wife and mother. In 1929 she was nominated Inspectora De Trabajo, which converted her standing from a charity worker to a state labor official, e.g. when contributing to Patronato De Previsión Social de Vizcaya y del Nacional De Recuperación De Inválidos Para El Trabajo; some of her activities brought her to other regions, e.g. to Catalonia. She addressed social issues by publishing in the press, be it local (El Nervión, La Gaceta del Norte, El Pueblo Vasco) or national (La Nación).

Republic

Urraca considered the fall of the monarchy a national disaster. In May 1931 she was detained by the police and fined 500 pesetas for promoting a meeting classified as conspiracy against the Republic. Later on this year she co-organised Agrupación de Defensa Femenina, a conservative female organisation grouping Alfonsine monarchists, Carlists and the Basque Emakumes, and was later asked to write the program draft. Extremely active, she helped to organise 50 meetings during four months. Her engagement did not go unnoticed; one of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party leaders Indalecio Prieto ridiculed her in the press stating that "the cavemen got their miss". Hostile to secular republican social and educational projects, she was fired as labor inspector in 1932.

Impressed by the local Acción Católica leader María Ortega de Pradera, wife of the Traditionalist theorist Victor Pradera, Urraca got exposed to Carlism. As she confessed, the movement attracted her due to its fanatical "courage and determination", especially against the bewilderement background of the alfonsine monarchism. In 1931-1933 she was gradually moving to Carlist positions, publishing in Carlist press and frequenting Carlist meetings; the Carlist militiamen Requetés greeted her with "Long Live Miss Cavemen" cry. Her new identity was confirmed when in 1933 she ran for the Cortes on the Traditionalist ticket from Gipuzkoa, narrowly missing the election. She continued her hectic propaganda activity across Spain, gaining nationwide recognition as an inflammatory and thrilling orator and greeted by homages from the Right and abuse from the Left.

Within Comunión Tradicionalista the role of Urraca was to organise Secciones Femeninas of the local Círculos, known as Margaritas. She continued her favourite social activities when setting up Socorro Blanco, the Carlist organisation for assistance to the members fined, imprisoned or otherwised penalised by the Republic. In the movement's press she campaigned for Cruzada Espiritual, intended as a campaign of prayer and self-sacrifice. Up to 1936 the Urraca-led Margaritas recruited 23,000 women (compared to 70,000 of Juventud Femenina de Acción Católica), mostly in Biscay, Gipuzkoa, Navarre and Catalonia. Urraca encouraged them to take courses in nursing (and took it herself), getting ready to the anticipated violent overthrow of the Republic. In 1936 she run for the parliament again, this time from Teruel, and lost despite a massive support campaign organised by various Carlist structures. In April 1936 she was detained for illegal possession of a pistol, another in a series of sanctions administered by the Republic, but was smuggled out of custody and spent the last few months of peace hiding in Burgos.

Civil War

During the first weeks of hostilities Urraca threw herself into organizing Carlist medical services, mostly recruiting women as nurses and auxiliary staff; she served as a nurse herself in the Northern and Guadarrama fronts throughout 1936. Following the forced political amalgamation of Carlism into the Francoist Falange Española Tradicionalista early 1937 she entered the party's Sección Femenina and became one of its leaders, along Pilar Primo de Rivera (sister of José Antonio Primo de Rivera) and Mercedes Sanz Bachiller (widow of Onésimo Redondo). Urraca assumed management of Delegación Nacional de Frentes y Hospitales, one of three branches of the feminine section (and one of 3 Carlists among 14 heads of all Nacional Delegaciones). In October 1937 she was appointed (as one of 11 Carlists) to the newly established, 50-member Consejo Nacional, a largely decorative executive body of the Falange.

In the rear of the frontline Urraca made an impressive figure, carrying a bottle in which she carried the cognac that she dispensed at arbitrary doses to the wounded. Even among the Nationalist enemies there are conflicting accounts as to Urraca's attitude towards the Republicans. According to some testimonies, she inflicted her Christian compassion upon the otherwise fanatical Carlist soldiers, and at times led the Requetés preventing the Falangists from executing the Republican prisoners. Other accounts point to her cruelty and suggest that she used to entice hatred and was co-responsible for some manslaughter actions carried out in the Nationalist zone. She is also quoted writing in her memoirs that the orphaned Republican children should not be treated the same way as the Nationalist ones. Paradoxically, in the Republican media Urraca did not enjoy less popularity than in the Nationalist ones. Press articles, when describing atrocities and terror of the Francoists, used to deride Urraca. The Madrid La Libertad deplored Nationalists' forced mobilisation of proletarian women "when ladies and damsels of Urraca Pastor hide in their homes, where they pray for the fascist cause"; the anarchist Solidaridad Obrera informed about the Moroccans raping Republican nurses and asked "what would Urraca Pastor say about this?", while the Barcelona La Vanguardia ridiculed the propaganda of "doña Urraca" during the battle of Teruel.

In the Francoist Falange Urraca clashed with Pilar Primo de Rivera. Apart from the rivalry of strong female personalities, the conflict was fuelled by discrepancy of conservative Catholic and modern sindicalist social visions, held by the two, and by the uneasy relations between the original Falange and the Comunión (during the Republic days Urraca was sometimes whistled down by the Falangists). The conflict crystallised on personal appointments of provincial leaders of Delegación Nacional de Frentes y Hospitales, badges designed for the service and creation of Cuerpo de Enfermeras. In line with general predominance of Falangists versus Carlists in the Francoist structures, Primo de Rivera got the upper hand and Urraca resigned from leadership posts in Sección Femenina in July 1938. She was not appointed to the next Consejo Nacional and dropped out of the FET executive, soon retiring to privacy and settling temporarily with her parents in Zaragoza.

Francoist Spain

.jpg)

Following the death of her mother in the early 1940s, Urraca moved with her aging father to Barcelona. Still in Zaragoza she befriended María Pilar Ros Martínez, widow of the Carlist Aragon leader Jesús Comín Sagüés, who was Catalan herself and who persuaded Urraca to move together. In the new, rather unfamiliar setting she strived to win new friends by turning her home into a cultural circle. On the commercial basis she was delivering charlas throughout the 1940s; she came to be known in the local media as ilustra charlista. The event, typically formatted as a semi-scholarly lecture on a given topic, in her case was often turning into a theatrical monodrama, a genre of a stage performance (and actually delivered in places like Teatro Olympia). Urraca's charlas-recitales tended to focus on art, usually poetry or painting; they were also dedicated to historical events, intended as praises of patriotic virtues.

In 1940 a Bilbao Catholic editing house issued Urraca's wartime memoirs, titled Así empezamos, memorias de una enfermera. When already in Barcelona, Urraca set up her own publishing house named MRUPSA (María Rosa Urraca Pastor Sociedad Anónima), which in the 1940s co-issued two biographical books she had written and edited herself: San Francisco de Borja (dedicated to a 16th-century Spanish Jesuit) and Lola Montes (dedicated to a 19th-century Irish dancer and courtesan). The enterprise did not turn very successful financially and no further books have been published. Starting in the mid-1950s Urraca tried to enhance the family finances, sustained systematically mostly by the military pension of her father, and started giving lessons in oratory skills and making public appearances in general. In the mostly Catalanist ex-Republican environment and with the Civil War memories still alive, the market for services of a former top Spanish Nationalist propagandist was not remarkable. Though initially Urraca advertised also teaching of castellano, later she dropped this feature from her press ads, which were appearing regularly in the local newspapers until the early 1970s. Since the death of her father in 1965, having no close family Urraca was increasingly alienated, also by the changing lifestyle patterns of the Spanish society. She maintained particularly close relationship with María Pilar Comín Ros, almost 20 years her junior and the Barcelona press pundit on women's fashion.

Urraca kept out of politics and was not active in the official Francoist structures. She refrained from activity also in the Carlist or Carlist-dominated organisations, some of them technically illegal though partially tolerated, and some functioning officially. She limited herself to maintaining personal relations with a few leaders of the movement, though the other ones regarded her – because of the Falangist episode – a traitor to the Traditionalist cause. Until her death she considered herself a Carlist. In a letter sent to La Vanguardia in 1982, Urraca confirmed her lifetime ideological identity and tried to defend it against critical press notes.

Reception and legacy

In the Francoist Spain Urraca Pastor was largely ignored by the regime's propaganda. Initially it was due to the influence of Pilar Primo de Rivera, who continuing with her Falangist top assignment ensured that the one-time rival to leadership in the female section of partido unico did not enjoy anything approaching prestigious standing. Later on the regime was gradually recalibrating its propaganda to appear less divisive and Urraca's earlier role of inflammatory orator did not quite fit in.

In the tightly censored media of the late 1940s an ex-Republican soldier turned comics artist, Miguel Bernet Toledano, was permitted to create and publicize her malicious alter-ego known as Doña Urraca, a comics figure to become sort of iconic character in the Spanish print. Though a direct reference has never been made and there were some visual differences between a character and its model, there is little doubt that the ugly black-dressed witch, always keen to abuse the weak with a sole purpose to do evil and using umbrella to deliver blows and punches was aimed to mock Urraca Pastor herself. In literature she marginally appeared in Mazurca para dos muertos (1983) by the literature Noble prize winner Camilo José Cela, presented as a lanky moustached nurse fancied by a wounded soldier, Camilo the gunner. She also appears (as bulky and ugly but still young-looking conspirator) in Inquietud en el Paraíso (2005) by Óscar Esquivias, a novel set in Burgos shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War.

Urraca's death in 1984 was acknowledged in the national media with not necessarily hostile melancholy. She is occasionally mentioned in both scholarly and public discourse, especially when discussing the role of women in the recent history of Spain. In this context she is sometimes compared to the famous Communist propagandist and thrilling orator Dolores Ibárruri Gómez as her Nationalist alter ego (or even dubbed la Pasionaria carlista). In a remote tiny Andalusian village of La Dehesa there is a street commemorating Urraca Pastor. Apart from a handful of related scholarly articles, she has earned one monography so far, a master thesis in gender studies accepted at Universidad de Salamanca in 2012. The author abandoned the customary portrait of Urraca as an ultraconservative and tried to re-define her as a modern Catholic women's activist.

See also

References

- María Dolores Andrés Prieto, La mujer en la política y la política de la memoria. María Rosa Urraca Pastor, una estrella fugaz [MA thesis], Salamanca 2012

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, London 1987, ISBN 978-0521086349, 0521086345

- Brian D. Bunk, Ghosts of Passion: Martyrdom, Gender, and the Origins of the Spanish Civil War, Durham 2007, ISBN 0822339439, 9780822339434

- María Beatriz Delgado Bueno, La Sección Femenina en Salamanca y Valladolid durante la Guerra Civil. Alianzas y rivalidades [PhD thesis], Salamanca 2009

- Nicholas Coni, Medicine and Warfare: Spain, 1936–1939, NY 2013, ISBN 1134170696, 9781134170692

- Iker González-Allende, ¿Ángeles en la batalla?: Representaciones de la enfermera en Champourcin y Urraca Pastor durante la guerra civil española, [in:] Anales de la literatura española contemporánea 34.1 (2009): 83-108.

- Frances Lannon, The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939, London 2002, ISBN 1841763691

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis], Valencia 2009

- Antonio Manuel Moral Roncal, María Rosa Urraca Pastor: de la militancia en Acción Católica a la palestra política carlista (1900-1936), [in:] Historia y politica 26 (2011), ISSN 15750361

External links

- MA monography on Urraca

- Urraca's father's military assignments

- Urraca's bio by Lannon

- Urraca by a Catalanist

- Urraca recollecting her youth in 1972

- Urraca's father's obituary

- Urraca's mother's obituary

- Urraca's evolution from ACM to Carlism

- Urraca speaking to a large audience (1933 photo)

- Rulebook of the Margaritas

- Urraca praised for saving lives of the Republicans

- Urraca accused of enticing to murder

- Margaritas as nurses (pro-Carlist site)

- Carlist nurses (a blog piece)

- Urraca's influence on Requetes

- medicine and warfare in Spain

- anarchist daily deriding Urraca (1937)

- Republican daily mocking Urraca (1937)

- rivalries in Seccion Femenina

- Urraca awarded Cruz Roja del Merito Militar (1939)

- Urraca's vision of a nurse analysed

- Urraca delivering charlas (1941)

- doña Urraca comics discussed at length

- Urraca as a traitor to the Carlist cause

- I am a Carlist; 1982 Urraca's letter to La Vanguardia

- Urraca's obituary

- they come, in numbers and weapons far greater than our own - Narnia version of the ultimate battle on YouTube

- Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda