Manor of Clovelly

The Manor of Clovelly is a historic manor in North Devon, England. Within the manor are situated the manor house known as Clovelly Court, the parish church of All Saints, and the famous picturesque fishing village of Clovelly. The parish church is unusually well-filled with well-preserved monuments to the lords of the manor, of the families of Cary, Hamlyn, Fane, Manners and Asquith. In 2015 the Rous family, direct descendants via several female lines of Zachary Hamlyn (1677-1759) the only purchaser of Clovelly since the 14th century, still own the estate or former manor, amounting to about 2,000 acres,[1] including Clovelly Court and the advowson of the parish church, and the village of Clovelly, run as a major tourist attraction with annual paying visitor numbers of about 200,000.[2]

Descent

Normans

Brictric/Queen Matilda

The manor of CLOVELIE was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as held at some time in chief from William the Conqueror by the great Saxon nobleman Brictric, but later held by the king's wife Matilda of Flanders (c.1031-1083).[3]

According to the account by the Continuator of Wace and others,[4] in his youth Brictric declined the romantic advances of Matilda and his great fiefdom was thereupon seized by her. Whatever the truth of the matter, years later when she was acting as Regent in England for William the Conqueror, she used her authority to confiscate Brictric's lands and threw him into prison, where he died.[5] Most of Matilda's landholdings, including Clovelly, descended to the Honour of Gloucester.[6]

Feudal barony of Gloucester

Brictric's lands were granted after the death of Matilda in 1083 by her eldest son King William Rufus (1087–1100) to Robert FitzHamon (died 1107),[7] the conqueror of Glamorgan, whose daughter and sole heiress Maud (or Mabel) FitzHamon brought them to her husband Robert de Caen, 1st Earl of Gloucester (pre-1100-1147), a natural son of Matilda's younger son King Henry I (1100–1135). Thus Brictric's fiefdom became the feudal barony of Gloucester.[8] The Giffard family later held Clovelly as feudal tenant of the Honour of Gloucester, and the Book of Fees records Roger Giffard holding Clovelly "from the part of Earl Richard",[9] that is Richard de Clare, 5th Earl of Hertford, 6th Earl of Gloucester (1222-1262), feudal baron of Gloucester. The feudal barony of Gloucester was soon absorbed into the Crown, when the Giffards became tenants in chief.

Giffard

The origin of the Giffard (alias Gifford) family of Devon is unclear. According to the Duchess of Cleveland's 1889 work The Battle Abbey Roll with some Account of the Norman Lineages,[11] the founder of this line was Berenger Giffard of Fonthill Gifford in Wiltshire, a younger brother of the great Walter Giffard (d.circa 1086), Lord of Longueville in Normandy, a Norman magnate and one of the 15 or so known Companions of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Walter was awarded by the Conqueror the feudal barony of Long Crendon,[12] in Buckinghamshire, comprising over 100 manors. He died at about the time of the production of the Domesday Book of 1086, in the Devonshire section of which Walter receives no mention as a landholder.[13]

Berenger's son was Osbern I Giffard (floruit 1130), who held lands in Devon in 1130. Osbern II Giffard held lands there in 1165.[14] According to the Duchess of Cleveland: "Another descendant, Andrew Giffard, in the time of King John (1199-1216), resigned his Wiltshire barony (sic[15]) to Robert Mandeville. Thenceforward the family solely belonged to the county of Devon, and divided into several branches". The Giffards survived in Devon longest at the manor of Brightley, Chittlehampton, which branch, formerly settled at Halsbury in the parish of Parkham, Devon, 4 miles south-west of Bideford, failed in the male line in 1715 on the death of Caesar Giffard. The earliest Giffard family of Devon held Weare Giffard and Clovelly, both in North Devon, but it is not clear how the various Devonshire branches were related.

According to the 1987 Victoria County History of Wiltshire, the family's chief seat of Fonthill Gifford in Wiltshire descended from Berenger Giffard eventually to Robert Giffard (fl. 1135) and to the latter's son Gerard Giffard (fl. 1172), who held Fonthill in 1159. He was succeeded by his son Robert Giffard (d. 1202/9), and then by the latter's brother Andrew Giffard (d.circa 1220), a priest, who with the king's assent resigned the lands to Robert Mauduit, William Cumin, William de Fontibus, and Robert de Mandeville, "presumably the husbands or descendants of four female coheirs". The eldest, Robert de Mandeville, became overlord of Fonthill Gifford.[16]

The Devon historians Tristram Risdon (d.1640)[17] and Sir William Pole (d.1635)[18] broadly agree with each other regarding the descent of Clovelly in the Giffard family, and include de Mandeville in the descent:

- Roger Giffard, who in 1242[19] held Clovelly as one knight's fee from Sir Walter Giffard of Weare Giffard.

- Matthew Giffard (son), tempore King Edward I (1272-1307), who according to Risdon left two daughters and co-heiresses, one married to Stanton, the other to Mandevile. Matthew Giffard presumably died before 1314 as in that year[20] Clovelly was held jointly by John de Stanton and John Maundeville. In 1345[21] Clovelly was held by Sir John de Stanton and Robert Mandevill. It appears that on an eventual split of the Giffard estates Mandeville inherited Fonthill Gifford in Wiltshire whilst Stanton received Clovelly. John de Stanton left a daughter and sole heiress Matilde de Stanton, wife of John Crewkern of Childhey in Dorset. During the reign of King Richard II (1377-1399) Clovelly was sold to Sir John Cary (d.1395),[22] as is generally accepted, although the Devon historian Thomas Westcote (d. circa 1637) in his View of Devonshire suggested that the latter inherited it from his mother Margaret Bozum, daughter of Richard Bozum[23] apparently of the family seated at Bozum's Hele, in the parish if Dittisham, Devon.[24]

Cary

The earliest known seat of the Cary family was the estate or manor of Cary, the location of which is uncertain, said by the Heraldic Visitations of Devon to be Castle Cary[26] in Somerset (in the recorded history of which a family named Cary does not however feature), elsewhere said to be somewhere in Devon.[27] At Torr Abbey in 1837 was a pedigree of the Cary family drawn up by the College of Arms on the order of Queen Anne Boleyn, whose sister Mary Boleyn was the wife of William Cary (d.1528) (see below), which commenced thus: "This pedigree contains a brief of that most ancient family and surname of the Caryes of Carye in the countie of Devon and it shows that how the family was connected with the noble houses of Beauford (sic), Beauchamp, Spencer, Somerset, Bryan, Fulford, Orchard, Holway, etc."[28] According to the Devon biographer John Prince (d.1723), relying on Risdon, the estate of Cary was in the parish of St Giles in the Heath, Devon, on the border with Cornwall.[29] The Devon historian Tristram Risdon (d.1640) stated the village of St Giles in the Heath to be "Hemmed in with the Tamer River on the one side and a pretty brook called Cary on the other; whereof (if I conceive not amiss) the surname of the Carys took beginning, for in this parish that family possessed an ancient dwelling bearing their name".[30]

The descent of Clovelly in the Cary family was as follows:[31]

Sir John Cary (d.1395)

Sir John Cary (d.1395), who purchased the manor of Clovelly, but probably never lived there and certainly died in exile in Ireland. He was a judge who rose to the position of Chief Baron of the Exchequer (1386-8) and served twice as Member of Parliament for Devon, on both occasions together with his brother Sir William Cary, in 1363/4 and 1368/9.[32] He was a son of Sir John Cary, Knight, by his second wife Jane de Brian, a daughter and co-heiress of Sir Guy de Brian[33] (d.1349) (alias de Brienne), of Walwyn's Castle in Pembrokeshire and Torr Bryan, on the south coast of Devon, and sister of Guy de Bryan, 1st Baron Bryan, KG (d.1390). He married Margaret Holleway, daughter and heiress of Robert Holleway.

Sir Robert I Cary (d. circa 1431)

Sir Robert Cary (d. circa 1431) (eldest son and heir) of Cockington, Devon, 12 times MP for Devon.[34] At some time after 1350[35] the Cary family acquired the manor of Cockington, in Devon, which they made their principal seat. Certainly according to Pole, Robert Cary held Cockington during the reign of King Henry IV (1399-1413).[36] He was an esquire in the households of King Richard II (1377-1399) and of the latter's half-brother John Holland, 1st Duke of Exeter (c.1352-1400).[37] He married as his first wife Margaret Courtenay, a daughter of Sir Philip I Courtenay (1340–1406), of Powderham, Devon, 4th (or 5th or 6th) son of Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (1303–1377) by his wife Margaret de Bohun (d.1391), daughter and heiress of Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford (1298–1322) by his wife Elizabeth Plantagenet, a daughter of King Edward I. Her eldest brother was Richard Courtenay (d.1415), Bishop of Norwich, a close friend and ally of Henry of Monmouth, later King Henry V (1413-1422), who did much to restore Robert Cary to royal favour after his father's attainder.[38][39]

Sir Philip Cary (d.1437)

Sir Philip Cary (d.1437), of Cockington, eldest son and heir, by his father's first wife.[40] He was MP for Devon in 1433. He married Christiana de Orchard (d.1472), daughter and heiress of William de Orchard of Orchard (later Orchard Portman), near Taunton in Somerset.

Sir William I Cary (1437-1471)

Sir William I Cary (1437-1471), of Cockington, son and heir. He was beheaded after the defeat of the Lancastrians at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471.[42] He is believed to be represented by a monumental brass of a knight, without surviving identifying inscription, set into a slate ledger stone on the floor of the chancel of All Saints Church, Clovelly, next to a smaller brass, in similar style, of his son and heir Robert Cary (d.1540).[43] He married twice:

Firstly to Elizabeth Poulett, a daughter of Sir William Poulett of Hinton St George, Somerset (ancestor of Earl Poulett), by whom he had issue:

Firstly to Elizabeth Poulett, a daughter of Sir William Poulett of Hinton St George, Somerset (ancestor of Earl Poulett), by whom he had issue:

- Robert Cary (d.1540), of Cockington, son and heir

Secondly he married Anna (or Alice) Fulford, a daughter of Sir Baldwin Fulford (d.1476) of Fulford, Devon, by whom he had progeny:

Secondly he married Anna (or Alice) Fulford, a daughter of Sir Baldwin Fulford (d.1476) of Fulford, Devon, by whom he had progeny:

- Thomas Cary of Chilton Foliat, Wiltshire, who married Margaret Spencer (1472-1536), (or Eleanor Spencer[44]), one of the two daughters and co-heiresses of Sir Robert Spencer (d. circa 1510), "of Spencer Combe", in the parish of Crediton in Devon, by his wife Eleanor Beaufort (1431-1501), daughter of Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset (1406-1455), KG. By Margaret Spencer he had two sons:

- Sir John Cary (1491–1552) of Plashey, eldest son, ancestor to the Cary Viscounts Falkland.[45]

- William Cary, her 2nd son, the first husband of Mary Boleyn, sister of Queen Anne Boleyn, and ancestor to the Cary Barons Hunsdon, Barons Cary of Leppington, Earls of Monmouth, Viscounts Rochford and Earls of Dover.[46]

- Thomas Cary of Chilton Foliat, Wiltshire, who married Margaret Spencer (1472-1536), (or Eleanor Spencer[44]), one of the two daughters and co-heiresses of Sir Robert Spencer (d. circa 1510), "of Spencer Combe", in the parish of Crediton in Devon, by his wife Eleanor Beaufort (1431-1501), daughter of Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset (1406-1455), KG. By Margaret Spencer he had two sons:

Robert II Cary (d.1540)

Robert Cary (d.1540), of Cockington and Clovelly, son and heir by first wife. His monumental brass showing a bare-headed knight dressed in full armour and standing in prayer, survives with its inscription, set into a ledger stone on the floor of the chancel of All Saints Church, Clovelly, inscribed as follows:

- Praye for the soule of Master Robert Cary Esquier sonne & heyer of Sur Will'm Cary, Knyght, whiche Robert decessyd the XVth day of June i(n) the yere of o(u)r Lord God MVCXL o(n) whos sowle J(es)hu have m(er)cy

He married thrice:[47]

- Firstly to Jane Carew, daughter of Nicholas Carew, Baron Carew (1424-1471),[48] of Mohuns Ottery, Luppitt, Devon, by whom he had two sons:

- John Cary (born 1502), eldest son and heir, who inherited the manor of Cary.

- Thomas Cary (d.1567), 2nd son, who inherited Cockington.

- Secondly to Ames Hody (alias Huddye), daughter of Sir William [49] Hody, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer 1486-1512, by whom he had a son:

- William Cary (d.1550) of Ladford

- Thirdly to Margaret Fulkeram (d.1547), daughter and heiress of William Fulkeram of Dartmouth, Devon, by whom he had issue:

- Robert III Cary (d.1586) of Clovelly (4th son).

Robert III Cary (d.1586)

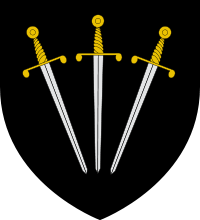

Robert III Cary (d.1586) of Clovelly, 4th son of his father, by his 3rd wife. He was given Clovelly by his father.[50] He was the first Cary to be seated exclusively at Clovelly, the manors of Cary and Cockington having been inherited by his half-brothers. He was a magistrate and along with several other members of the Devonshire gentry then serving as magistrates he died of gaol fever at the Black Assize of Exeter 1586. He married Margaret Milliton, daughter of John Milliton and widow of John Giffard of Yeo in the parish of Alwington, North Devon. His large monument, with strapwork decoration, survives against the south wall of the chancel of All Saints Church, Clovelly. Along the full length of the cornice is inscribed in gilt capitals: Robertus Carius, Armiger, obiit An(no) Do(mini) 1586[51] ("Robert Cary, Esquire, died in the year of Our Lord 1586"). On the base of the north side are shown two relief sculpted heraldic escutcheons, showing Cary impaling Chequy argent and sable, a fess vairy argent and gules[52] (Fulkeram, for his father) and Cary impaling Sable, three swords pilewise points in base proper pomels and hilts or (Poulett, for his grandfather). On the base of the west side is a similar escutcheon showing his own arms of Cary (of four quarters, 1st: Cary; 2nd: Or, three piles in point azure (Bryan);[53] 3rd: Gules, a fess between three crescents argent (Holleway);[54] 4th: A chevron (unknown, possibly Hankford: Sable, a chevron barry nebuly argent and gules[55]) impaling Gules, a chevron or between three millets hauriant argent (Milliton[56])

George I Cary (1543-1601)

George I Cary (1543-1601), eldest son and heir, Sheriff of Devon in 1587. He constructed at Clovelly a harbour wall, surviving today, described by Risdon as "a pile to resist the inrushing of the sea's violent breach, that ships and boats may with the more safety harbour there".[60] Clovelly's main export product was herring fish, which formerly appeared at certain times of the year in huge shoals, close off-shore in the shallow waters of the Bristol Channel, and such a harbour wall was a great benefit to the village fishermen, tenants of the Cary lords of the manor. He married thrice:

- Firstly to Christiana Stretchley, daughter and heiress of William Stretchley of Ermington in Devon and widow of Sir Christopher Chudleigh (1528-1570)[61] of Ashton, by whom he had issue including:

- William Cary (1576-1652) of Clovelly, JP, eldest son and heir.

- Secondly to Elizabeth Bampfield, eldest daughter of Richard Bampfield (1526-1594) of Poltimore, Devon, Sheriff of Devon in 1576;[62] without issue.

- Thirdly in 1586 to Catherine Russell (d.1632), of Sussex, by whom he had 3 sons and 3 daughters.

His monumental brass survives in Clovelly Church in the form of a ledger stone on the floor of the chancel, inset into which is an inscribed brass tablet and below which in the 1860s[63] was added into an empty matrix a reproduction large monumental brass in the form of a bishop's crozier. It is unclear what relevance such an object might have to him and when the original brass which once filled the matrix was removed or robbed. The Latin inscription is as follows:

- Epithaphium inditum viri insignissimi curatoris pacis & qui(eti)ssimi et Musar(um) patroni dignissimi Georgii Caret (sic) Armigeri qui obiit decimo die Julii anno Domini 1601. En ubi vir situs est pietate et pace beatus justitiae cultor relligionis amans multorum exemplar, patriae decus, anchora pacis ingenio, forma Pallade, Marte potens. Dum vixit Christum coluit, sic orbe recessit in sancta stabilis relligione Dei. Nunc capit in caelis solatia grata laborum; nunc requiem aeterni carpit in arce poli.

- ("A funeral oration set in place of a most distinguished man, a most neutral guardian of the peace and a most worthy patron of the Muses, of George Cary, Esquire, who died on the tenth day of July in the year of Our Lord 1601. Behold where is placed a man, blessed with piety and peace, a cultivator of justice, a lover of religion, an example of (for) many, an ornament to his country, in his character an anchor of peace, in his (physical) form like (the Titan) Pallas, powerful in Martial feats. While he lived he worshipped Christ, thus he withdrew from the world firm in the holy religion of God. Now at one time he takes in the Heavens deserved consolation of his labours, at another time he seizes the rest of eternity in the vault of the sky").[64]

William II Cary (1576-1652)

William II Cary (1576-1652), JP for Devon, MP for Mitchell, Cornwall, in 1604,[65] eldest son and heir by his father's first wife. He is sometimes said to be the model for Will Cary featured in Westward Ho!,[66] the 1855 novel by Charles Kingsley (1819-1875), who appears in the narrative concerning the Spanish Armada in 1588, although he would have been a boy aged just 12 at the time. However the "daring foreign exploits attributed to him are entirely fictional".[67] Kingsley spent much of his childhood at Clovelly as his father was Rev. Charles Kingsley, Curate of Clovelly 1826-1832 and Rector 1832-1836. Indeed the author's small brass monumental tablet is affixed to the wall of the church under the mural monument of Sir Robert Cary (1610-1675), eldest son of William II Cary (1576-1652).[68] He married thrice:

- Firstly in 1598 to Gertrude Carew (d.1604), widow of John Arundell of Tolverne, Cornwall and daughter of the antiquarian and historian of Cornwall Richard Carew (1556-1620) of Antony in Cornwall,[69] author of the Survey of Cornwall (1602), Sheriff of Cornwall (1583 and 1586), and MP for Saltash in 1584. Prince relates a "facete fancy" concerning this marriage:[70]

- "That her father the morning after, after observing her a little sad, awakened her with this question: 'What! melancholly, daughter, after the next day of your wedding?' 'Yes sir' said she 'and with great reason; for yesterday 'twas care-you, now 'tis care-I' (which is much better in pronouncing than writing), alluding to the change of her name from Carew to Cary".

By Gertrude Carew he had two daughters, including Phillipa Cary (1603-1633), wife of John Docton of Docton, whose ledger stone survives in Clovelly Church.

- Secondly to Dorothy Gorges (d.1622), eldest daughter of Sir Edward Gorges of Wraxall, Somerset by his wife Dorothy Speke. Her monument survives in the Speke Chantry in Exeter Cathedral. By Dorothy Gorges he had issue including:

- Sir Robert Cary (1610-1675), of Clovelly, eldest son and heir, a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber to King Charles II. He died without progeny. His mural monument survives in Clovelly Church.

- Rev. George Cary (1611-1680), of Clovelly, 2nd son, Dean of Exeter and Rector of Shobrooke in Devon. His mural monument survives in Clovelly Church.

- Thirdly in 1631 to Jane Elworthy, widow of Narcissus Mapowder of Holsworthy, Devon.

His mural monument survives on the south chancel wall of Clovelly Church, erected by his 2nd son and eventual heir George (who erected a similar one also opposite on the north chancel wall to his elder brother Sir Robert),[71] inscribed as follows:

- "In memory of William Cary Esqr who served his king and country in ye office of a Justice of Peace under three princes, Q. Elizabeth, King James and King Charles the I and having served his generation dyed in the 76 yeare of his age Ano Dom 1652: Omnis Caro Foenum".

The arms top centre are Cary; the arms top left and right are: Lozengy or and azure, a chevron gules (Gorges (modern)), for his second wife Dorothy Gorges (d.1622), mother of the erector of the monument. These arms were the subject of one of the earliest and most famous heraldic law cases brought concerning English armory, Warbelton v Gorges in 1347. The final sentence in Latin Omnis Caro Foenum, is from Isiah 40:6 ("All flesh is grass") and is a pun on the name Cary, but was commonly used on monuments elsewhere, for example on the monumental brass coffin plate of Richard III Duke (1567-1641) of Otterton, in Otterton Church, Devon.[72]

Sir Robert IV Cary (1610-1675)

Sir Robert IV Cary (1610-1675), eldest son and heir, a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber to King Charles II. He died unmarried and without progeny. His mural monument survives in Clovelly Church, erected by his younger brother and heir George Cary (1611-1680) and inscribed as follows:

- "In memory of Sr Robert Cary Kt (sonne and heyre of William) Gentleman of the Privy Chamber unto King Charles the 2d who having served faithfully that glorious prince, Charles the Ist, in the long Civil Warr against his rebellious subjects, and both him and his sonne as a Justice of Peace, he dyed a batchelour in the 65 yeare of his age An. Dom. 1675. Peritura Perituris Reliqui".

The last sentence in Latin ("I have left behind those things destined to perish with those people destined to perish") is a reference to Seneca, On Providence.[73] Above are the arms and crest of Cary.

Dr. George II Cary (1611-1680)

Doctor George II Cary (1611[74]-1680), younger brother, was a Professor (Doctor) of Divinity, Dean of Exeter (amongst other duties responsible for the maintenance and decoration of the cathedral building) and Rector of Shobrooke in Devon. He was one of the Worthies of Devon of John Prince (d.1723).[75] He married Anne Hancock, daughter of William II Hancock (d.1625), lord of the manor of Combe Martin, Devon, by whom he had numerous progeny.[76] He was educated at Exeter Grammar School and in 1628 entered Queens College, Oxford but later moved to Exeter College, Oxford, much frequented by Devonians. His first clerical appointment was by his father as Rector of Clovelly. Following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, he was appointed Chaplain in Ordinary to King Charles II, after which he received the honour of a Doctorate in Divinity from Oxford University. At the bequest of the Lord Chamberlain he preached a Lent sermon before the king, for which was much thanked by the Archbishop of Canterbury.[77] During most of his career he lived about 44 miles south-east of Clovelly, at Exeter, and at Shobrooke, near Crediton, 9 miles to the north-west of Exeter. Indeed it appears that until about 1702 Clovelly was occupied by his second cousins, the three brothers John Cary, George Cary (d.1702) and Anthony Cary (d.1694), sons of Robert Cary of Yeo Vale, Alwington,[78] near Clovelly. He rebuilt the rectory house at Shobrooke, which he found in a dilapidated state and made it "a commodious and gentile dwelling".[79] He also rebuilt the "ruinous,...filthy and loathsome" Dean's House in Exeter, which during the Civil War had been let to negligent tenants by the See of Exeter, and "in a short time so well repaired, so thoroughly cleansed and so richly furnished this house that it became a fit receptacle for princes".[80] As the Emperor Augustus with the City of Rome, so did Dean Cary with the Dean's House in Exeter "found it ruines but he left it a palace", as Prince suggests.[81] Indeed King Charles II stayed there on the night of 23 July 1670, having visited the newly built Citadel in Plymouth. It was also the chosen abode of Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle, Lord lieutenant of Devon, for three weeks in 1675 and again during the Monmouth Rebellion. He was a liberal benefactor in assisting the Corporation of Exeter in the completion in 1699 of the cutting of a leat between Exeter Quay and Topsham, which fed into a pool which could shelter 100 ships. He twice refused offers of the Bishopric of Exeter made by King Charles II, on vacancies arising in 1666 and 1676. The reason for his first refusal, or profession of Nolo Episcopari, is unknown, but he refused the second time due to age and infirmity which would prevent him attending Parliament as would be required.[82] He died at Shobrooke but was buried in Cloveely Church. His mural monument survives in Clovelly Church, erected by his eldest son Sir George Cary (1654-1685),[83] the armorials of the latter's two wives appearing on the top of the monument as follows: dexter: Azure, a chevron between three mullets pierced or (Davie of Canonteign, Christow); sinister: Or, a lion reguardant sable langued gules (Jenkyn of Cornwall). The Latin inscription is as follows:[84]

- Georgius Cary S(acrae) T(heologiae) P(rofessor) Decanus B(eat)i Petri Exon(iensis), vir omnibus dignitatibus major quem ipsa latebra licet ei solum in deliciis non potuit abscondere. Nemo magis invitus cepit nemo magis adornavit cathedram ut lux e tenebris sic illustravit ecclesiam. In omnibus concionibus, hospitiis, conciliis antecelluit. Pectore, lingua calamo, praepotens. In justa causa nemini cedens; in injusta abhorrens lites. Fratribus in ecclesiae negotiis nunquam sese opposuit nisi rationibus et in his semper victor. Erga regem iniquissimis temporibus infractae fidelitatis: post reditum erat ei a sacris. Caelestem vero non aulicam petiit gratiam, quae tamen nolentem sequebatur, nam bis vocante Carolo Secundo, bis humillime respondit: Nolo Episcopari. Obiit die Purificationis B(eatae) Virginis A(nn)o Aet(atis) (suae) 72, A(nn)o Dom(ini) 1680.

Which may be translated as:

- "George Cary, Professor of Sacred Theology, Dean of the Blessed St Peter of Exeter, a man greater in all things worthy than concealment allowed to him, ((?)only in delights he was not able to conceal). No man more against his will took possession of, no man more beautified a cathedral; As light out of shadow, thus he lit up the Church. In all assemblies, guest-chambers and councils he distinguished himself. In his heart, tongue and pen, (he was) exceedingly mighty. In a just cause ceding to no man; in an unjust (cause) abhorring strife. In affairs of business he never opposed himself to his brothers in the Church, unless for (good) reasons, and in those always the victor. Towards the king in the most evil times (he was) of unbroken fidelity. Afterwards to him was given back ((?)by those things which are holy). Indeed he sought heavenly grace, not grace in the court of kings, which nevertheless against his wishes followed him, for at the two-fold call of Charles II twice he replied in the greatest humility: "I am unwilling to wear the Bishop's Mitre" (lit: "to be bishoped"). He died on the day of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin, in the year of his age 72,(sic) in the year of Our Lord 1680".

Sir George III Cary (1654-1685)

Sir George III Cary (1654-1685), eldest son and heir. He was knighted by King Charles II during his father's lifetime and in 1681 served as Member of Parliament for Okehampton, Devon,[85] and occupied the honourable position of Recorder of Okehampton. He married twice as follows, but left no progeny:[86]

- Firstly in 1676 to Elizabeth Jenkyn (1656-1677), daughter and co-heiress (with her sisters Anne Jenkyn, wife of Sir John St Aubyn, 1st Baronet (1645–1687), of Trekenning, MP for Mitchell and Catherine Jenkyn, wife of John Trelawny (c.1646-1680) of Trelawny, MP for West Looe) of James Jenkyn of Trekenning, St. Columb Major, Cornwall. The arms of Jenkyn (Or, a lion reguardant sable langued gules) are shown on the top sinister of the monument Sir George Cary erected to his father in Clovelly Church. By Elizabeth Jenkyn, who died aged 21, he had one son Robert Cary who died an infant. Her mural monument survives in Clovelly Church.

- Secondly in 1679 to Martha Davie, daughter and heiress of William Davie of Canonteign, Christow, Devon. The arms of Davie of Canonteign (Azure, a chevron between three mullets pierced or) (a variant of Davie of Creedy, Sandford) are shown on the top dexter of the monument Sir George Cary erected to his father in Clovelly Church. Without issue.

His mural monument survives in Clovelly Church, with arms of Cary above, inscribed thus:

- "In memory of Sr George Cary Kt sonne and heire of Dr George Cary Dean of Exon who dyed the 6th day of Janry in the 31 year of his age Ano Dom 1684/5. Ne amemines vitam quam si in bonis accenseret numen justis non raperet". (Do not .... life, .... God would not seize away the Just if he had not counted them amongst the Good)

William III Cary (c.1661-1710)

William III Cary (c.1661-1710), younger brother, twice Member of Parliament for Okehampton in Devon 1685-1687 and 1689-1695 and also for Launceston in Cornwall 1695-1710.[87] His mural monument survives in Clovelly Church. In 1704 he obtained a private Act of Parliament to allow him to sell entailed lands in Somerset and to re-settle his Devon estates in order to pay debts and provide incomes for his younger children. He was suffering financial difficulties and applied to Robert Harley for a lucrative government post to restore his finances:[88]

- "...by 16 or 17 years of war my estate, which mostly lies near the sea, has felt more than ordinary calamities of it, and hath been lessened in its income beyond most of my neighbours living in the inland country, and that a considerable jointure upon it, and four small children and the Act of Parliament procured last session for dismembering it, are motives which concur with my ambition to serve her Majesty".

He married twice:

- Firstly, after 1683, to Joan Wyndham (1669-1687), a daughter of Sir William Wyndham, 1st Baronet (c.1632-1683) of Orchard Wyndham, Watchet, Somerset, Member of Parliament for Somerset 1656-1658 and for Taunton 1660-1679. She died aged 18 and was buried in the Wyndham Chapel of St Decuman's Church, Watchet, Somerset. Without issue. Her mural monument survives in Clovelly Church, showing at the top the arms of Cary impaling Wyndham: Azure, a chevron between three lion's heads erased or, which arms on escutcheons are also held by a pair of putti below. the monument is inscribed as follows:

- "In memory of Joan the wife of William Cary of Clovelly Esqr daughter of Sr William Wyndham of Orchard Wyndham in the county of Somersett, Baronett, who dyed Febry the 4th 86/7 in the 18th year of her age and lys buryed in St Decomans Church Somersett. En forma, moribus, virtutibus vere egregiam! Sed cum egregiam dicimus hic tacemus lugentes (i.e. "Behold! in her appearance, morals and virtues (she was) truly outstanding! But when we say outstanding, here we are silent, lamenting")

- Secondly in 1694 to Mary Mansel (d.1701), daughter of Thomas I Mansel of Briton Ferry, Glamorgan, MP, and sister of Thomas II Mansel, MP. She brought a large dowry of £5,000. her mural monument survives in Clovelly Church inscribed as follows:

- "In memory of Mary the wife of William Cary of ys parish, Esqr who was buried the 6th of February 1700. Also in memory of Robert Cary of ys parish Esqr who departd ys life ye 7th of March 1723. Als in memory of Mrs Ann Cary who departd ys life ye 23 of May 1728. This monument was erected by the desire of ye said Mrs Ann Cary and performd by her sister Mrs Elizabeth the last of ye family & now wife to Rob'rt Barber Esq of Ashmore in ye county of Dorset"

By Mary Mansel he had progeny 3 sons and 2 daughters, which generation was the last of the Cary family of Clovelly:

- Robert Cary (1698-1724), eldest son, who died aged 26. His ledger stone slab survives on the floor of the chancel of Clovelly Church. He is also mentioned on the monument to his mother in Clovelly Church.

- William Cary (1698-1724), died aged 26.[89]

- George Cary (1701-1701), 3rd son, died an infant.

- Ann Cary (1695-1728), eldest daughter, died unmarried aged 33. Her ledger stone slab survives on the floor of the chancel of Clovelly Church. She is also mentioned on the monument to her mother in Clovelly Church.

- Elizabeth Cary (1699-1738), youngest daughter, wife of Robert Barber (d.1758) of Ashmore in Dorset, by whom she had issue 2 sons and 4 daughters. She was the last of the Carys of Clovelly,[90] which manor was sold in 1739, one year after her death, to Zachary Hamlyn. Her mural monument, a marble tablet, survives in St Nicholas's Church, Ashmore, (now in the vestry, formerly on the north wall) inscribed as follows:[91]

- "In memory of Elizabeth, wife of Robert Barber of Ashmore, in the county of Dorset, Esq., by whom she left two sons, viz. : Robert Cary Barber and Jacob; and four daughters, viz. : Ann, Elizabeth, Lucy and Molly. She was daughter of William Cary of Clovelly, in the county of Devon, Esq. He was member of Parliament for Launceston, in the county of Cornwall. His first wife was Joan, aunt to the present Sir Will. Windham. His second wife Mary, daughter of Thomas Mansell of Britton Ferry, in the county of Glamorgan, Esq., nearly related to Lord Mansell. She was the last of the family of the Carys of Clovelly aforesaid, who descend from the ancient branch of the noble family of which was and are Cary Lord Hunsdon, Cary Lord Faulkland, Cary Lord Lepington and Monmouth, Sir Robert and Sir George Cary. She died in May 1738".

- A space is left for the day of her death, which has never been filled in. She was not buried at Ashmore. On the monument are shown the arms of Barber (Argent, two chevrons between three cinquefoils gules) with inescutcheon of pretence of Cary.

Sources

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitation of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, pp. 150–9, pedigree of Cary

- Lauder, Rosemary, Devon Families, Tiverton, 2002, pp. 131–6, Rous of Clovelly

- Griggs, William, A Guide to All Saints Church, Clovelly, first published 1980, Revised Version 2010

References

- ↑ Lauder, Rosemary, Devon Families, Tiverton, 2002, pp.131-6, Rous of Clovelly, p.136

- ↑ Lauder, p.135

- ↑ Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 1, 1:59 (Bideford). In the Domesday Book a heading above the entry for Northlew, two entries above the entry for Clovelly, states: Infra scriptas terras tenuit Brictric post regina Mathildis ("Brictric held the undermentioned lands and later Queen Matilda")

- ↑ Thorn, Caroline & Frank, (eds.) Domesday Book, (Morris, John, gen.ed.) Vol. 9, Devon, Parts 1 & 2, Phillimore Press, Chichester, 1985, part 2 (notes), 24,21, quoting "Freeman, E.A., The History of the Norman Conquest of England, 6 vols., Oxford, 1867–1879, vol. 4, Appendix, note 0"

- ↑ Edward Augustus Freeman, The History of the Norman Conquest of England, Vol. IV (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1871), pp. 761–64

- ↑ Thorn & Thorn, Part 2 (notes), chapter 25

- ↑ Round, J. Horace, Family Origins and Other Studies, London, 1930, The Granvilles and the Monks, pp.130-169, p.139

- ↑ Sanders, I.J. English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086–1327, Oxford, 1960, p.6, Barony of Gloucester

- ↑ Thorn & Thorn, Part 2 (notes), 1:59

- ↑ Pole, pp.484-5

- ↑ The Battle Abbey Roll with some Account of the Norman Lineages

- ↑ Sanders, I.J. English Baronies: A Study of their Origin and Descent 1086-1327, Oxford, 1960, pp.62-4

- ↑ Thorn & Thorn, part 2, Index of Persons, under Walter, no entry for Walter Giffard

- ↑ Cleveland, Duchess of

- ↑ Fonthill Gifford is not recognised as a feudal barony in Sander's work of 1960

- ↑ Freeman, Jane & Stevenson, Janet H., Victoria County History, Wiltshire, Volume 13: South-West Wiltshire: Chalke and Dunworth Hundreds, ed. D A Crowley (London, 1987), pp. 155-169, Parishes: Fonthill Gifford

- ↑ Risdon, Tristram (d.1640), Survey of Devon, 1811 edition, London, 1811, with 1810 Additions, p.241

- ↑ Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, pp.371-2

- ↑ Per Pole, regnal year 27 King Henry III

- ↑ Per Pole, regnal year 8 King Edward II

- ↑ Per Pole, regnal year 19 King Edward III

- ↑ Pole, p.371; Risdon, p.241

- ↑ As quoted in Prince, p.187; Vivian, p.150

- ↑ Risdon, pp.167-8; Pole, p.291

- ↑ Vivian, p.150

- ↑ Vivian, p.150

- ↑ Vivian, p.151 "John Cary of Cary in Com. Devon" (i.e. Latin: in comitatu Devoniae, "in the county of Devon"), referring to his 16th century descendant

- ↑ Burke, John, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland Enjoying Territorial Possessions or High Official Rank but Uninvested with Heritable Honours, 4 volumes (1833-1838), Vol.2, London, 1837, p.34, pedigree of Cary of Torr Abbey, footnote

- ↑ Prince, p.176

- ↑ Risdon, Tristram (d.1640), Survey of Devon, 1811 edition, London, 1811, with 1810 Additions, p.229

- ↑ Vivian, 1895

- ↑ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitation of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.150, pedigree of Cary; See also biography of his son Sir Robert Cary in History of Parliament

- ↑ Vivian, p.150, the Heraldic Visitation states she was a co-heiress of her father, which appears unlikely as he is known to have had a son and heir Guy de Bryan, 1st Baron Bryan, KG (d.1390)

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of Cary, Robert (d.c.1431), of Cockington, Devon

- ↑ Risdon, p.148, regnal year 24 king Edward III

- ↑ Pole, p.278

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of Cary, Robert (d.c.1431), of Cockington, Devon

- ↑ HoP biography of Robert Cary

- ↑ Vivian, pp.244,246, pedigree of Courtenay; p.150, pedigree of Cary, in which wife given incorrectly as Elizabeth Courtenay (footnote 6)

- ↑ Roskell History of Parliament; Vivian, apparently incorrectly, gives him as the son of his father's 2nd wife Jane Hankford

- ↑ Griggs, William, A Guide to All Saints Church, Clovelly, first published 1980, Revised Version, 2010, p.5

- ↑ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitation of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.150, pedigree of Cary

- ↑ Griggs, William, A Guide to All Saints Church, Clovelly, first published 1980, Revised Version, 2010, p.5

- ↑ Vivian, p.150, pedigree of Cary

- ↑ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitation of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, pp.150, 154-6, pedigree of Cary

- ↑ Vivian, pp.150, 154-6, pedigree of Cary

- ↑ Vivian, p.150

- ↑ Vivian, p.135, pedigree of Carew

- ↑ "John" Hody, per Vivian, p.150. he was the son of Sir John Hody (died 1441) (see History of Parliament biography of John Hody ) Chief Justice of the King’s Bench

- ↑ Pole, p.371

- ↑ Griggs, p.4

- ↑ Pole, p.483 Fulkeray

- ↑ Pole, p.473

- ↑ Pole, p.488

- ↑ Pole, p.486; Griggs, p.4, states the chevron is for Fulford, yet his grandfather's 2nd wife Anna/Alice Fulford, daughter of Sir Baldwin Fulford, was not an heiress (she had a brother) and thus the Fulford arms would not be quartered by the Cary family, according to the laws of heraldry

- ↑ Pole, p.493; A "millet" is a type of fish, possibly a mullet

- ↑ Pole, p.372; Risdon, p.241

- ↑ Griggs, 2010, p.5

- ↑ Griggs, William, A Guide to All Saints Church, Clovelly, first published 1980, Revised Version 2010, p.5

- ↑ Risdon, p.241

- ↑ Vivian, p.189, pedigree of Chudleigh

- ↑ Vivian, p.39, pedigree of bampfield

- ↑ Griggs, 2010, p.5

- ↑ Translation based on Griggs, p.5, corrected and expanded

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of Cary, William (c.1578-1652), of Clovelly Court and Exeter, Devon

- ↑ Griggs, p.7

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of Cary, William (c.1578-1652), of Clovelly Court and Exeter, Devon

- ↑ Griggs, p.7

- ↑ Vivian, p.139, pedigree of Carew

- ↑ Prince, p.187

- ↑ Prince, p.189

- ↑ see File:RichardDuke MargaretBasset Brass OttertonChurch Devon.JPG

- ↑ L. ANNAEI SENECAE DIALOGORVM LIBER I AD LVCILIVM QVARE ALIQVA INCOMMODA BONIS VIRIS ACCIDANT, CVM PROVIDENTIA SIT DE PROVIDENTIA) V, 7: accipimus peritura perituri ("we receive what is perishable and shall ourselves perish", literally: "we who are about to perish receive things about to perish"; See works of Robert Leighton, Archbishop of Glasgow: "We are here inter peritura perituri; the things are passing which we enjoy, and we are passing who enjoy them", and "We accept that we, destined ourselves to perish, live amongst things also destined to perish".

- ↑ Some doubt exists as to the date of his birth, which his mural monument makes 1608, derived from the date of his death being given as 1680 and his age 72. However that would have made him his father's eldest son and heir of Clovelly before his brother Sir Robert Cary (1610-1675), which was not the case. Vivian gives his date of birth as 1611. Prince, who transcribed his monumental inscription otherwise entirely accurately, appears to have deliberately mis-transcribed the last line as "MDCLXXX" (i.e. 1680) in place of "1680" and "LXIX" (i.e. 69) in place of "72"

- ↑ Prince, John, (1643–1723) The Worthies of Devon, 1810 edition, London

- ↑ Vivian, p.441, pedigree of Hancock; given erroneously on p.159 as "John" Handcock (sic)

- ↑ Prince, p.188

- ↑ Vivian, p.158, refers to the brothers George Cary (d.1702) and Anthony Cary (d.1694) (sons of Robert Cary of Yeo Vale, Alwington) as "of Clovelly", and notes that the infant son of their eldest brother John Cary was buried at Clovelly

- ↑ Prince, p.188

- ↑ Prince, p.189

- ↑ Prince, p.189

- ↑ Prince, p.188

- ↑ Prince, John, (1643–1723) The Worthies of Devon, 1810 edition, London, p.190, states it was erected by his second son William Cary (c.1661-1710), apparently incorrect on the basis of the armorials

- ↑ Transcribed from monument 2015; transcript, with date of death mis-transcribed, given in Prince, p.191

- ↑ History of parliament biography of Cary, Sir George (c.1653-85), of Clovelly, Devon

- ↑ History of parliament biography of Cary, Sir George (c.1653-85), of Clovelly, Devon

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of Cary, William (c.1661-1710), of Clovelly, Devon

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of Cary, William (c.1661-1710), of Clovelly, Devon

- ↑ According to Vivian, p.159, he was buried in Bristol Cathedral where survives his monument. This appears to confuse him with another Willian Cary (1713-1759) who was Chancellor of Bristol cathedral

- ↑ Vivian, p.159

- ↑ Watson, E.W., Ashmore, Co. Dorset: A History of the Parish with Index to the Registers, 1651 to 1820, published 1890, p.84