Manila Light Rail Transit System

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Light Rail Transit Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Manila, Philippines | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transit type | Rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of lines | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of stations | 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 2.8 million (2013) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | Light Rail Transit Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Began operation |

December 1, 1984 (LRT-1) April 5, 2003 (LRT-2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Light Rail Transit Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of vehicles |

Line 1 (LRT-1): BN/ACEC Hyundai Precision/Adtranz Kinki Sharyo/Nippon Sharyo Line 2 (LRT-2): Hyundai Rotem | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System length |

33.4 km (20.8 mi) (total) LRT-1: 19.65 km (12.2 mi) LRT-2: 13.8 km (8.6 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Overhead line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Average speed | 40 km/h (25 mph) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Top speed | 80 km/h (50 mph) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Manila Light Rail Transit System, popularly and informally known as the LRT, is a metropolitan rail system serving the Metro Manila area in the Philippines. Although referred to as a light rail system because it originally used light rail vehicles, it has characteristics that make it more akin to a rapid transit (metro) system, such as high passenger throughput, exclusive right-of-way and later use of full metro rolling stock. The system is operated by the Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA), a government-owned and controlled corporation under the authority of the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC). Along with the Manila Metro Rail Transit System (MRT-3, also called the new Yellow Line), and Philippine National Railways's commuter line, the system makes up Metro Manila's rail infrastructure.

Quick and inexpensive to ride, the system serves 2.1 million passengers each day. Its 33.4 kilometers (20.8 mi) of mostly elevated route form two lines which serve 31 stations in total. LRT Line 1 (LRT-1), also called the Green Line (formerly Yellow Line), opened in 1984 and travels a north–south route. LRT Line 2 (LRT-2), the Blue Line (formerly Purple Line), was completed in 2004 and runs east–west. The original LRT-1 was built as a no-frills means of public transport and lacks some features and comforts, but the new LRT-2 has been built with additional standards and criteria in mind like barrier-free access. Security guards at each station conduct inspections and provide assistance. A reusable plastic magnetic ticketing system has replaced the previous token-based system, and the Flash Pass introduced as a step towards a more integrated transportation system.

Many passengers who ride the system also take various forms of road-based public transport, such as buses, to and from a station to reach their intended destination. Although it aims to reduce traffic congestion and travel times in the metropolis, the transportation system has only been partially successful due to the rising number of motor vehicles and rapid urbanization. The network's expansion is set on tackling this problem.

Network

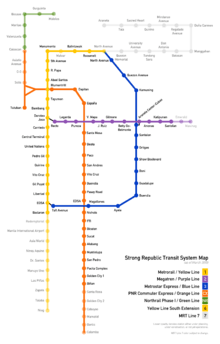

The network consists of two lines: the original LRT Line 1 (LRT-1) or Green Line, and the more modern LRT Line 2 (LRT-2), or Blue Line. The LRT-1 is aligned in a general north–south direction along over 17.2 kilometers (10.7 mi) of fully elevated track. From Monumento it runs south above the hustle and bustle of Rizal and Taft Avenues along grade-separated concrete viaducts allowing exclusive right-of-way before ending in Baclaran.[1][2] A four-station east–west extension along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue that will connect Monumento to the North Avenue MRT Station is currently under construction. Including the extension's two recently opened stations, Balintawak and Roosevelt, the LRT-1 has twenty stations.[3][4] The LRT-2 or Line 2 consists of eleven stations in a general east–west direction over 13.8 kilometers (8.57 mi) of mostly elevated track, with one station lying underground. Commencing in Recto, the line follows a corridor defined by Claro M. Recto and Legarda Avenues, Ramon Magsaysay and Aurora Boulevards, and the Marikina-Infanta Highway before reaching the other end of the line at Santolan.[5] The system passes through the cities of Caloocan, Manila, Marikina, Pasay, Pasig, Quezon City, and San Juan.

Every day around 430,000 passengers board the LRT-1, and 175,000 ride the LRT-2.[6][7] During peak hours, the LRT-1 fields 24 trains; the time interval between the departure of one and the arrival of another, called headway, is a minimum of 3 minutes. The LRT-2 runs 12 trains with a minimum headway of 5 minutes.[8] With the proper upgrades, the Yellow Line is designed to potentially run with headway as low as 1.5 minutes.[9] The LRT-2 can run with headway as low as 2 minutes with throughput of up to 60,000 passengers per hour per direction (pphpd).[10]

In conjunction with the MRT-3—also known as the new Yellow Line, a similar but separate metro rail system operated by the private Metro Rail Transit Corporation (MRTC)—the system provides the platform for the vast majority of rail travel in the Metro Manila area. Together with the PNR, the three constitute the SRTS.[11] Recto and Doroteo Jose serve as the sole interchange between both lines of the LRTA. Araneta Center-Cubao and EDSA stations serve as interchanges between the LRTA and the MRTC networks. To transfer lines, passengers will need to exit from the station they are in then pass through covered walkways connecting the stations.[12] Blumentritt LRT Station meanwhile is immediately above its PNR counterpart.

Baclaran, Central Terminal, and Monumento are the LRT-1's three terminal stations; Recto, Araneta Center-Cubao, and Santolan are the terminal stations on the LRT-2. All of them are located on or near major transport routes where passengers can take other forms of transportation such as privately run buses and jeepneys to reach their ultimate destination both within Metro Manila and in neighboring provinces. The system has two depots: the LRT-1 uses the Pasay Depot at LRTA headquarters in Pasay, near Baclaran station, while the LRT-2 uses the Santolan Depot built by Sumitomo in Pasig.[1][5][10][13]

The LRT-1 and LRT-2 are open every day of the year from 5:00 am PST (UTC+8) until 10:00 pm on weekdays, and from 5:00 am until 9:30 pm on weekends, except when changes have been announced. Notice of special schedules is given through press releases, via the public address system in every station, and on the LRTA website.[14]

History

The system's roots date back to 1878, when an official from Spain's Department of Public Works for the Philippines submitted a proposal for a Manila streetcar system. The system proposed was a five-line network emanating from Plaza San Gabriel in Binondo, running to Intramuros, Malate, Malacañan Palace, Sampaloc and Tondo. The project was approved and in 1882, Spanish businessman Jacobo Zobel de Zangroniz, Spanish engineer Luciano M. Bremon, and Spanish banker Adolfo Bayo, founded the Compañia de los Tranvias de Filipinas to operate the concession granted by the Spanish colonial government. The Malacañan Palace line was later replaced with a line linking Manila to Malabon, and construction began in 1885. Four German-made steam-operated locomotives and eight coaches for nine passengers each, composed the initial assets of the company. The Manila-Malabon line was the first line of the new system to be finished, opening to the public on October 20, 1888, with the rest of the network opening in 1889.[15] From the beginning it proved to be a very popular line, with services originating from Tondo as early as 5:30 a.m. and ending at 7:30 p.m., while trips from Malabon were from 6:00 a.m. until 8:00 p.m., every hour on the hour in the mornings, and every half hour beginning at 1:30 p.m. in the afternoon.[16]

With the American takeover of the Philippines, the Philippine Commission allowed the Manila Electric Railroad and Light Company (Meralco) to take over the properties of the Compañia de los Tranvias de Filipinas,[17] with the first of twelve mandated electric tranvia (tram) lines operated by Meralco opening in Manila in 1905.[18] At the end of the first year around 63 kilometers (39 mi) of track had been laid.[19] A five-year reconstruction program was initiated in 1920, and by 1924, 170 cars serviced many parts of the city and its outskirts.[19] Although it was an efficient system for the city's 220,000 inhabitants, by the 1930s the streetcar network had stopped expanding.[18][19][20]

The system was closed during World War II. By the war's end, the tram network was damaged beyond repair amid a city that lay in ruins. It was dismantled and jeepneys became the city's primary form of transportation, plying the routes once served by the tram lines.[18] With the return of buses and cars to the streets, traffic congestion became a problem. In 1966, the Philippine government granted a franchise to Philippine Monorail Transport Systems (PMTS) for the operation of an inner-city monorail.[21] The monorail's feasibility was still being evaluated when the government asked the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) to conduct a separate transport study.[20] Prepared between 1971 and 1973, the JICA study proposed a series of circumferential and radial roads, an inner-city rapid transit system, a commuter railway, and an expressway with three branches.[20] After further examination, many recommendations were adopted; however, none of them involved rapid transit and the monorail was never built. PMTS' franchise subsequently expired in 1974.[22]

Another study was performed between 1976 and 1977, this time by Freeman Fox and Associates and funded by the World Bank. It originally suggested a street-level railway, but its recommendations were revised by the newly formed Ministry of Transportation and Communications (now the DOTC). The ministry instead called for an elevated system because of the city's many intersections.[18] However, the revisions increased the price of the project from ₱1.5 billion to ₱2 billion. A supplementary study was conducted and completed within three months.

President Ferdinand Marcos created the Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA) on July 12, 1980, by virtue of Executive Order No. 603[23] giving birth to what was then dubbed the "Metrorail". First Lady Imelda Marcos, then governor of Metro Manila and minister of human settlements, became its first chairman. Although responsible for the operations of the LRT-1 and LRT-2, the LRTA primarily confined itself to setting and regulating fares, planning extensions and determining rules and policies, leaving the day-to-day operations to a sister company of Meralco called the Meralco Transit Organization (METRO Inc.).[24] Initial assistance for the project came in the form of a ₱300 million soft loan from the Belgian government, with an additional ₱700 million coming from a consortium of companies comprising SA Ateliers de Constructions Electriques de Charleroi (ACEC) and BN Constructions Ferroviaires et Métalliques (today both part of Bombardier Transportation), Tractionnel Engineering International (TEI) and Transurb Consult (TC).[24][25] Although expected to pay for itself from revenues within twenty years of the start of operation, it was initially estimated that the system would lose money until at least 1993. For the first year of operation, despite a projected ₱365 million in gross revenue, losses of ₱216 million were thought likely.[20]

Construction of the LRT Line 1 started in September 1981 with the Construction and Development Corporation of the Philippines (now the Philippine National Construction Corporation) as the contractor with assistance from Losinger, a Swiss firm, and the Philippine subsidiary of Dravo, an American firm. The government appointed Electrowatt Engineering Services of Zürich to oversee construction and eventually became responsible for the extension studies of future expansion projects.[20] The line was test-run in March 1984, and the first half of LRT-1, from Baclaran to Central Terminal, was opened on December 1, 1984. The second half, from Central Terminal to Monumento, was opened on May 12, 1985.[1] Overcrowding and poor maintenance took its toll a few years after opening. In 1990, the LRT-1 fell so far into disrepair due to premature wear and tear that trains headed to Central Terminal station had to slow to a crawl to avoid further damage to the support beams below as cracks reportedly began to appear.[18] The premature ageing of LRT-1 led to an extensive refurbishing and structural capacity expansion program with a help of Japan's ODA.[26]

For the next few years LRT-1 operations ran smoothly. In 2000, however, employees of METRO Inc. went on strike, paralyzing LRT-1 operations from July 25 to August 2, 2000. Consequently, the LRTA did not renew its operating contract with METRO Inc. that expired on July 31, 2000, and assumed all operational responsibility.[1] At around 12:15 pm on December 30, 2000, a bomb—later learned to have been planted by Islamic terrorists—went off in the front coach of a LRT-1 train pulling into Blumentritt station, killing 11 and injuring over 60 people in the most devastating of a series of attacks that day, now known as the Rizal Day bombings.[27][28]

With Japan's ODA amounting to 75 billion yen in total, the construction of the LRT Line 2 began in the 1990s, and the first section of the line, from Santolan to Araneta Center-Cubao, was opened on April 5, 2003.[29] The second section, from Araneta Center-Cubao to Legarda, was opened exactly a year later, with the entire line being fully operational by October 29, 2004.[30] During that time the LRT-1 was modernized. Automated fare collection systems using magnetic stripe plastic tickets were installed; air-conditioned trains added; pedestrian walkways between Lines 1, 2, and MRT-3 Lines completed.[12] In 2005, the LRTA made a profit of ₱68 million, the first time the agency made a profit since the LRT-1 became operational in 1984.[31]

Stations

With the exception of Katipunan (which is underground), the LRTA's 31 stations are elevated.[1][3][5] They follow one of two different layouts. Most LRT-1 stations are composed of only one level, accessible from the street below by stairway, containing the station's concourse and platform areas separated by fare gates.[32] The boarding platforms measure 100 meters (328 ft 1 in) long and 3.5 meters (11 ft 6 in) wide.[2] Baclaran, Central Terminal, Carriedo, Balintawak, Roosevelt and North Avenue stations on the LRT-1, and all LRT-2 stations are composed of two levels: a lower concourse level and an upper platform level (reversed in the case of Katipunan). Fare gates separate the concourse level from the stairs and escalators that provide access to the platform level. All stations have side platforms except for Baclaran, which has one side and one island platform, and Santolan, which has an island platform.

The concourse area at LRTA stations typically contain a passenger assistance office (PAO), ticket purchasing areas (ticket counters and/or ticket machines), and at least one stall that sells food and drinks.[33] Terminal stations also have a public relations office.[34] Stores and ATMs are usually found at street level outside the station, although there are instances where they can be found within the concourse.[10] Some stations, such as Monumento, Libertad and Araneta Center-Cubao, are directly connected to shopping malls.[12] LRT-2 stations have two restrooms, but LRT-1 restrooms have been the subject of criticism not only because of the provisioning of a single washroom at each station expected to serve all passengers (whether male, female, disabled or otherwise), but also because of the impression that the lavatories are poorly maintained and unsanitary.[35]

Originally, the LRT Line 1 was not built with accessibility in mind. This is reflected in the LRT-1's lack of barrier-free facilities such as escalators and elevators. It is also inconvenient in other ways: for one, because of the use of side platforms, passengers wishing to access the other platform for the train bound in the opposite direction at single-level LRT-1 stations need to exit the station (and by extension, the system) and pay a new fare. The newer LRT Line 2, unlike its counterpart, is designed to be barrier-free and allows seamless transfer between platforms. Built by a joint venture between Hanjin and Itochu, LRT-2 stations have wheelchair ramps, braille markings, and pathfinding embossed flooring leading to and from the boarding platforms in addition to escalators and elevators.[5][10][36]

In cooperation with the Philippine Daily Inquirer, copies of the Inquirer Libre—a free, tabloid-size, Tagalog version of the Inquirer broadsheet—are available at selected LRTA stations from 6:00 am until the supply runs out.[34]

Rolling stock

Four types of rolling stock run on the system, with three types used on the LRT Line 1 and another used on the LRT Line 2. The LRT Line 1 railway cars were made either in Belgium by La Bruggeoise et Nivelle, South Korea by Hyundai Precision and Adtranz (La bruggeoise et Nivelle and Adtranz are now part of Bombardier Transportation), or Japan by Kinki Sharyo and Nippon Sharyo.[5][24][37] The LRT Line 2, unlike the LRT Line 1, runs heavy rail metro cars made in South Korea by Hyundai Rotem and provided by the Asia-Europe MRT Consortium led by Marubeni Corporation that have higher passenger capacity and maximum speed.[38] All four types of rolling stock are powered by electricity supplied through overhead wires.

Of the two LRTA lines, the LRT Line 2 prominently employs wrap advertising in its rolling stock. The LRT Line 1 have begun using wrap advertising as well initially for their second-generation trains, followed by their third-generation trains.

LRT Line 1

The LRT Line 1 at various stages in its history has used a two-car, three-car, and four-car train. The two-car trains are the original first-generation BN trains (railway cars numbered from 1000). Most were transformed into three-car trains, although some two-car trains remain in service. The four-car trains are the more modern second-generation Hyundai Precision and Adtranz (numbered from 1100) and third-generation Kinki Sharyo / Nippon Sharyo (1200) trains.[39][40] There are 139 railway cars grouped into 40 trains serving the line: 63 of these are first-generation cars, 28 second-generation, and 48 third-generation. One train car (1037) was severely damaged in the Rizal Day bombings and was subsequently decommissioned.[8] The maximum speed of these cars is 80 kilometers per hour (50 mph).[24][37]

As part of the second phase of expansion on the Yellow Line, 12 new trains made in Japan by Kinki Sharyo and provided by the Manila Tren Consortium were shipped in the third quarter of 2006 and went into service in the first quarter of 2007. The new air-conditioned trains have boosted the capacity of the line from 27,000 to 40,000 passengers per hour per direction.[40][41][42]

LRT Line 2

The LRT Line 2 fleet runs eighteen heavy rail four-car trains with lightweight stainless car bodies and 1,500 volt electric motors. They have a top speed of 80 kilometers per hour (50 mph) and usually take around thirty minutes to journey from one end of the line to the other.[43] Each train measures 3.2 meters (10 ft 6 in) wide and 92.6 meters (303 ft 10 in) long allowing a capacity of 1,628 passengers: 232 seated and 1,396 standing.[5] Twenty sliding doors per side facilitate quick entry and exit. The line's trains also feature air conditioning, driverless automatic train operation from the Operations Control Center (OCC) in Santolan, low-noise control, enabled electric and regenerative braking, and closed-circuit television inside the trains.[44][45] Special open spaces and seats are designated for wheelchair users and elderly passengers, and automatic next station announcements are made for the convenience of passengers, especially for the blind.[5][36]

Safety and security

The system has always presented itself as a safe system to travel on, and despite some incidents a World Bank paper prepared by Halcrow deemed the running of metro rail transit operations overall as "good".[46] Safety notices in both English and Tagalog are a common sight at the stations and inside the trains. Security guards with megaphones can be seen at boarding areas asking crowds to move back from the warning tiles at the edge of platforms to avoid falling onto the tracks.[8] In the event of emergencies or unexpected events aboard the train, alerts are used to inform passengers about the current state of the operations. The LRTA uses three alerts: Codes Blue, Yellow, and Red.

| Alert | Indication |

|---|---|

| Code Blue | Increased interval time between train arrivals |

| Code Yellow | Slight delay in the departure and arrival of trains from stations |

| Code Red | Temporary suspension of all train services due to technical problems |

Smoking, previously banned only at station platforms and inside trains, has been banned at station concourse areas since June 24, 2008.[47] Hazardous chemicals, such as paint and gasoline, as well as sharp pointed objects that could be used as weapons, are forbidden.[48] Full-sized bicycles and skateboards are also not allowed on board the train, although the ban on folding bicycles was lifted on November 8, 2009.[49][50] Those under the influence of alcohol may be denied entry into the stations.[48]

In response to the Rizal Day bombings, a series of attacks on December 30, 2000 that included the bombing of a LRT-1 train among other targets, and in the wake of greater awareness of terrorism following the September 11 attacks, security has been stepped up on board the system. The Philippine National Police has a special police force assigned at LRT-1 and LRT-2 [51] and security police provided by private companies are assigned to all stations with each having a designated head guard. Closed-circuit televisions have been installed to monitor stations and keep track of suspicious activities.[5] To better prepare for and improve response to any adverse incidents, drills simulating terror attacks and earthquakes have been conducted.[8][52] It is standard practice for bags to be inspected upon entry into stations by guards equipped with hand-held metal detectors. Those who refuse to submit to such inspection may be denied entry.[53] Since May 1, 2007, the LRTA has enforced a policy against making false bomb threats, a policy already enforced at airports nationwide. Those who make such threats can face penalties in violation of Presidential Decree No. 1727, as well as face legal action.[54] Posted notices on station walls and inside trains remind passengers to be careful and be wary of criminals who may take advantage of the crowding aboard the trains. To address concerns of inappropriate contact on crowded trains, the first coach of Yellow Line trains have been designated for females only.[34]

Fares

The Manila Light Rail Transit System is one of the least expensive rapid transit systems in Southeast Asia, costing significantly less to ride than other systems in the region.[55][56] Fares are distance-based, ranging from 12 to 20 Philippine pesos (₱), or about 29 to 47 U.S. cents (at US$1 = ₱42 as of September 2011), depending on the number of stations traveled to reach the destination.[57][58] Unlike other transportation systems, in which transfer to another line occurs within a station's paid area, passengers have to exit and then pay a new fare for the line they are entering. This is also the case on the Yellow Line when changing boarding platforms to catch trains going in the opposite direction.

The Line 1 uses two different fare structures: one for single journey tickets and another for stored value tickets. Passengers using single journey tickets are charged ₱12, ₱15, or ₱20 depending on the number of stations traveled or whether the newly opened Balintawak or Roosevelt station is part of their trip. Stored value tickets are charged on a more finely graduated basis with fares ranging from ₱12 to ₱19.[57][59] The Line 2, on the other hand, has only one fare structure. Passengers are charged ₱12 for the first three stations, ₱13 for a journey of four to six stations, ₱14 for seven to nine stations and ₱15 for a trip along the entire line.[58]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ticketing

Before 2001, passengers on the LRT Line 1 would purchase a token to enter the station. Subsequent upgrades in the fare collection system eventually transitioned the Yellow Line from a token-based system to a ticket-based system, with full conversion to a ticket-based system achieved on September 9, 2001.[60] Passengers can enter the system paid areas with either a single journey or stored value magnetic stripe plastic ticket or a Flash Pass. On the Yellow Line, tickets are sold from ticket booths manned by station agents; on the Purple Line they can also be procured from ticket machines.[5]

Magnetic ticket

Currently the system uses two types of tickets: a single journey (one-way) ticket whose cost is dependent on the destination, and a stored value (multiple-use) ticket available for ₱100.[58] Senior citizens and disabled passengers can receive fare discounts as mandated by law. Tickets would normally bear a picture of the incumbent president, though some ticket designs have done away with this practice.

Single journey tickets are only valid on the day of purchase and will be unusable afterward. They expire if not used to exit the same station after 30 minutes from entry or if not used to exit the system after 120 minutes from entry. If the ticket expires, the passenger will be required to buy a new one.

Stored value tickets are usable on either the LRT-1 or LRT-2 lines although a new fare will be charged when transferring from one line to the other. To reduce ticket queues, the LRTA is promoting the use of stored value tickets. Aside from benefitting from a lower fare structure on the LRT-1, stored value ticket users can avail of a scheme called the Last Ride Bonus that grants the use of any residual amount in a stored value ticket less than the usual minimum ₱12 fare, or the appropriate fare for the station of arrival from the station of departure, as a full fare.[56] Stored value tickets are not reloadable and are captured by the fare gate after the last use. They expire six months after the date of first use.[58]

Tickets are used both to enter and exit the paid area of the system. A ticket inserted into a fare gate at the station of origin is processed and then ejected allowing a passenger through the turnstile. The ejected ticket is then retrieved while passing through so that it can be used at the exit turnstile at the destination station to leave the premises. Tickets are captured by the exit turnstiles to be reused by the system if they no longer have any value. If it is a stored value ticket with some value remaining, however, it is once again ejected by the fare gate to be taken by the passenger for future use.[32]

Flash Pass

To better integrate the LRTA and MRTC networks, a unified ticketing system utilizing contactless smart cards, similar to the Octopus card in Hong Kong and the EZ-Link card in Singapore, was made a goal of the SRTS.[61][62] In a transitional move towards such a unified ticketing system, the Flash Pass was implemented on April 19, 2004, as a stopgap measure.[63] However, plans for a unified ticketing system using smart cards have languished,[64] leaving the Flash Pass to fill the role for the foreseeable future. Originally sold by both the LRTA and the Metro Rail Transit Corporation, the Blue Line operator, the pass was discontinued with the election of Benigno Aquino III as President of the Philippines in 2010.

The pass consisted of two parts: the Flash Pass card and the Flash Pass coupon.[65] A nontransferable Flash Pass card used for validation had to be acquired before a Flash Pass coupon can be purchased. To obtain a card, a passenger needed to visit a designated station and fill out an application form. Although the card is issued free of charge and contains no expiry date, it is expected to be issued only once. Should it be lost, an affidavit of loss had to be submitted before a replacement can be issued. The Flash Pass coupon, which served as a ticket, was linked to the passenger's Flash Pass card through the card number printed on the coupon. Coupons were sold for ₱250 and were valid for unlimited rides on all three lines of the LRTA and MRTC for one week.[65] The card and coupon were used by showing them to a security guard at an opening along the fare gates, who after checking their validity allowed the holder to pass through.[63]

Future expansion

Plans for expanding the LRTA network have been formulated throughout its history, and successive administrations have touted trains as one of the keys to relieving Metro Manila of its long-standing traffic problems.[66] Expansion of the system was one of the main projects mentioned in a ten-point agenda laid out by former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in 2005.[67]

Extensions

A southern extension of LRT-1, also known as LRT-6, is planned. The envisioned line would have 10 stations over 11.7 kilometers (7.3 mi) ending in Bacoor in the province of Cavite. It would be the first line extending outside the Metro Manila area. An unsolicited bid to build and operate this project from Canada's SNC-Lavalin was rejected by the Philippine government in 2005. The government is working with advisers (International Finance Corporation, White & Case, Halcrow, and others) to conduct an open-market invitation to tender for the construction of the extension and a 30-year concession to run it. An additional extension from Bacoor to Imus and from there a further extension to Dasmariñas, both in Cavite, are also being considered.[68][69][70]

As of March 2012, the government announced that the P60 billion LRT-1 south extension project has already been approved by the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) with the bidding expected to take place by the end of March or early April 2012.[71]

The LRTA is also currently conducting studies on the feasibility of a 6.2-kilometer (3.9 mi), four-station LRT-1 spur from Baclaran towards Terminal 3 of the Ninoy Aquino International Airport, with a projected daily capacity of 40,000 passengers. Funding for the project could be sourced from either official development assistance or a public-private partnership.[72]

There is also a proposal for a 4-kilometer (2.5 mi) eastern extension of the LRT Line 2 from Marikina, crossing into Cainta in Rizal and finally to Masinag Junction in Antipolo, also in Rizal. The line could later be extended as far west as Manila North Harbor and as far east as Cogeo in Antipolo.[73] The construction of the eastern extension to Masinag was approved by the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) in September 2012.[74]

New lines

MRT-7 is a planned 13-station, 21-kilometer (13 mi) line that starts in Quezon City and traverses Commonwealth Avenue, passing through Caloocan City and ending in the city of San Jose del Monte in Bulacan. This line finished the bidding stage and has been approved by the Department of Justice and the Department of Transportation and Communications.[75] As of August 2010 the MRT-7 project is under review due to various concerns from several local governments where the rail project is proposed to run through, and may undergo major changes from the original. On May 2012, the consortium of Marubeni-DMCI won the contract to build MRT-7 for around $1 billion and would take an estimated 42 months to build starting early 2013.[76]

MRT-8, or the East Rail Line, is a proposed 48-kilometer (30 mi) line crossing through Metro Manila and the provinces of Laguna and Rizal. Several tunnel sections between the municipalities of Pililla in Rizal and Santa Cruz in Laguna would be built in the process. Phase I of the line would begin in Santa Mesa in Manila and end in Angono in Rizal, and would consist of 16.8 kilometers (10.4 mi) of elevated track, following the general alignment of Shaw Boulevard and Ortigas Avenue.[77]

Transfer of line operations

DOTC Undersecretary for Public Information Dante Velasco has unveiled a study being conducted by the DOTC looking at the possibility of transferring operations of Line 3 (MRT 3) from Metro Rail Transit Corporation (MRTC) to LRTA thus uniting Lines 1, 2,and 3 under one operator to improve maintenance costs and to form a more integrated transportation system. According to DOTC Undersecretary For Rails Glicerio Sicat, the transfer is set by the government in June 2011.[78]

As of January 13, 2011, Light Rail Transit Authority Chief Rafael S. Rodriguez took over as officer-in-charge of MRT-3 in preparation for the integration of operations of LRT-1, LRT-2, and MRT-3 Lines.[79]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 The LRT Line 1 System - The Yellow Line. [ca. 2010]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 United Nations Centre for Human Settlements. (1993). Provision of Travelway Space for Urban Public Transport in Developing Countries. UN–HABITAT. pp. 15, 26–70, 160–179. ISBN 92-1-131220-5.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "LRT opens Balintawak station". (March 22, 2010). ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ↑ Kwok, Abigail (October 22, 2010). "New LRT station opens in Quezon City". Philippine Daily Inquirer (Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inc.). Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 The LRT Line 2 System - The Purple Line. [ca. 2010]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.lrta.gov.ph/kpi_line1.htm

- ↑ http://www.lrta.gov.ph/kpi_line2.htm

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Light Rail Transit Authority. Planning Department/MIS Division. (2007). Light Rail Transit Authority Annual Report 2006 (PDF). Author. pp. 18–20. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ Gardner, Geoff and Francis Kuhn. (1992). Appropriate Mass Transit in Developing Cities. Paper presented at the 6th World Conference on Transport Research, Lyon, June, 1992. p. 7. Retrieved March 11, 2010 from UK Department for International Development's Transport-Links Website.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Halcrow. (2010). Manila light rail transit – Purple Line. Retrieved May 16, 2010 from Halcrow Website.

- ↑ Villanueva, Marichu. (July 15, 2003). "GMA Launches transit system". The Philippine Star. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 The Missing Links: Now a Reality. [ca. 2006]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ "Contact Us". [ca. 2010]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ↑ Train Schedule. [ca. 2010]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ↑ R. De la Torre, Visitacion (1981). Landmarks of Manila, 1571-1930. Manila: Filipinas Foundation. p. 41.

- ↑ de los Reyes, Isabelo (1890). "III". El folk-lore Filipino. University of the Philippines Press. Appendix "Malabon Monográfico".

- ↑ The Philippines’ Oldest Business House. Makati: Filipinas Foundation. 1984. pp. 68–70.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Satre, Gary L. (June 1998). "The Metro Manila LRT System—A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Japan Railway and Transport Review 16: 33–37. Retrieved May 8, 2006.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Manila Electric Company (Meralco). (November 10, 2004). "History of Meralco". Retrieved January 18, 2010 from the Meralco Website.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "Light Rail Transit Authority Company History". Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ Republic of the Philippines. (Approved: June 14, 1966). Republic Act No. 4652 - An Act Granting the Philippine Monorail Transit System, Incorporated a Franchise to Establish, Maintain and Operate a Monorail Transportation Service in the City of Manila and Suburbs and Cebu City and Province. Retrieved December 13, 2009 from the Chan Robles Virtual Law Library.

- ↑ Republic of the Philippines. (Enacted: October 4, 1971). Republic Act No. 6417 - An Act Amending Sections Three And Seven Of Republic Act Numbered Forty-Six Hundred Fifty-Two, Entitled "An Act Granting the Philippine Monorail Transit System, Incorporated a Franchise to Establish, Maintain and Operate a Monorail Transportation Service in the City Of Manila and Suburbs and Cebu City and Province". Retrieved December 13, 2009 from the Chan Robles Virtual Law Library.

- ↑ ,Republic of the Philippines. (July 12, 1980). "Executive Order No. 603". Retrieved February 15, 2010 from the Light Rail Transit Authority Website.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Razon, Evangeline M. (June 1998). "The Manila LRT System" (PDF). Japan Railway and Transport Review 16: 38–39. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- ↑ Net Resources International. [ca. 2010]. "Manila Light Rail Extension, Philippines". Railway Technology. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ↑ Japan International Cooperation Agency. "LRT Line 1 Capacity Expansion Project" (PDF). JICA official page.

- ↑ Aning, Jerome. (December 31, 2000). "Bodies tell of deadly force of LRT blast". The Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ↑ GMA News Research. (January 23, 2009). "Rizal Day bombing chronology". GMA News. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ↑ Japan International Cooperation Agency. "Metro Manila Strategic Mass Rail Transit Development" (PDF). JICA Official Page.

- ↑ Bergonia, Allan. (October 28, 2004). "LRT-2 Recto Station Opens". People's Journal. Retrieved May 11, 2006 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ "LRTA posts profit, pays P23M in income taxes". (April 24, 2006). Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved May 6, 2006 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Mga Gabay sa Pasaherong Sasakay ng LRT [Tips for Passengers Riding the LRT]. [ca. 2010] (in Filipino). Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ↑ Light Rail Transit Authority. (August 21, 2008). Environmental Impact Statement for the Light Rail Transit Line 1 South Extension Project (Report No. E1970). Retrieved March 26, 2010 from the World Bank Website.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Customer Services. [ca. 2010]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ↑ Ongoy, Lym R. (December 25, 2007). "Just one restroom for everyone at every LRT station". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "LRT 2, Victory Liner are PWD-Friendly: PAVIC". Light Rail Transit Authority. August 2, 2004. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Otaki, Tsutomu. (2007). "The Commissioning – In Case of a Project in Manila" (PDF). KS World (Kinki Sharyo) 14: 12–13. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ Marubeni Philippines. [ca. 2010]. Infrastructure. Retrieved February 17, 2010 from the Marubeni Philippines Website.

- ↑ The LRT Line 1 Capacity Expansion Project (Phase I). [ca. 2003]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Kinki Sharyo. [ca. 2010]. Light Rail Transit Authority, Manila Philippines, Light Rail Vehicle. Retrieved March 8, 2010 from the Kinki Sharyo Website.

- ↑ "3rd Generation LRV Mock Up on Display". Light Rail Transit Authority. March 9, 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2006. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ Olchondra, Riza T. (December 7, 2006). "'3G' trains to serve LRTA riders Dec. 11: More comfortable, safer rides assured for commuter". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ↑ Rotem. Total Rail Systems Division. (January 2005). "Rotem Ranks 3rd in Global Metro System Supply: SCI" (PDF). Rolling into the Future 1: 5. Retrieved February 10, 2010 from www.industrykorea.net.

- ↑ Toshiba. (2003). "Power Systems and Industrial Equipment" (PDF). Science and Technology Highlights 2003: A Special Issue of Toshiba Review. p. 19. Retrieved February 10, 2010 from the Toshiba Website.

- ↑ Electronics Systems Package for Manila LRT Line 2, Philippines (PDF). Singapore Technologies Engineering. ST Electronics. [ca. 2006]. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ↑ World Bank. (December 2, 2004). "A Tale of Three Cities: Urban Rail Concessions in Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Manila – Final Report" (PDF). Author. p. 17. (Prepared by Halcrow Group Limited).

- ↑ Uy, Veronica. (June 24, 2008). LRTA enforces no smoking policy. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Ruiz, JC Bello. (October 26, 2009). "LRTA reminders for holidays". The Manila Bulletin. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ↑ Kwok, Abigail. (November 6, 2009). "Bike your way to work on board LRT’s ‘green zones’". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Bike O2 Project". Light Rail Transit Authority. 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ↑ Del Puerto, Luigi A. and Tara V. Quismundo. (November 13, 2004). "New task force formed to keep LRT, MRT safe". The Daily Tribune. Retrieved February 15, 2010 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ Punay, Edu. (July 31, 2006). LRTA holds bomb drill at Central terminal. The Philippine Star. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ↑ Ruiz, JC Bello. (December 7, 2009). Wrapped gift items inspected at LRT, MRT rail stations. The Manila Bulletin. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ↑ Olchondra, Riza T. (May 3, 2007). LRTA warns commuters: No bomb jokes, or else.... Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ↑ "LRT Fares Lowest in Southeast Asia". Light Rail Transit Authority. December 5, 2003. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "LRT Passengers Urged to Use Stored Value Ticket". Light Rail Transit Authority. December 10, 2003. Retrieved April 8, 2006.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "LRTA Rationalizes Fare Structure". Light Rail Transit Authority. December 12, 2003. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 Ticket and Fare Structure. [ca. 2010]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ↑ Fare Rationalization Matrix for LRT Line 1 System. (March 22, 2010). Retrieved March 26, 2010 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ The Automated Fare Collection System (AFCS) Project. [ca. 2006]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ↑ "LRT, MRT smart cards for commuters". The Manila Bulletin. December 10, 2003. Retrieved February 22, 2010 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ Casanova, Sheryll B. (February 4, 2004). "Single Pass Rail Ticket May Be Ready Ahead of Schedule". The Manila Times. Retrieved April 7, 2006 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Marfil, Jude O. (April 20, 2004). "For LRT, MRT riders: 1 ticket, 3 lines". Manila Standard. Retrieved February 22, 2010 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ "Integrated Ticketing Systems for Various LRT Lines". National Economic and Development Authority. Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Flash Pass Ticketing System. [ca. 2006]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ↑ Virola, Romulo A. (October 12, 2009). "Land Transport in the Philippines: Retrogressing Towards Motorcycles?". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ Republic of the Philippines. Office of the President. (July 21, 2005). "SONA 2005 Executive Summary". Retrieved February 20, 2010 from the Republic of the Philippines Office of the Press Secretary Website.

- ↑ Ho, Abigail L. (October 13, 2003). "LRTA set to bid out $841-M light rail project". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved April 7, 2006 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ Batino, Clarissa S. (April 20, 2005). "LRT-1 consortium seeks gov't. guarantee". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved April 7, 2006 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ Light Rail Transit Authority. (2010). The LRT Line 1 South Extension Project. Retrieved February 20, 2010 from the LRTA Website.

- ↑ NEDA approves LRT-1 extension, 11 other projects, Public-Private Partnership Center, Retrieved March 23, 2012

- ↑ "NAIA Rail Link Project". Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ↑ "The Metro Manila Strategic Mass Rail Transit Development Project: Line 2". [ca. 2006]. Light Rail Transit Authority. Retrieved April 6, 2006.

- ↑ Neda Board OKs 9 big projects, Business Mirror, retrieved September 6, 2012

- ↑ Cruz, Neal. (November 14, 2007). "MRT 7 may end Metro traffic problems". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ↑ http://business.inquirer.net/59447/marubeni-to-build-1b-philippine-rail-project

- ↑ Wakefield, Francis T. (2009). "American firm proposes $900-M MRT project in Rizal". The Manila Bulletin. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ↑ Govt creates team for MRT 3 due dilligence, sets June takeover, The Manila Times, December 28, 2010

- ↑ LRTA chief takes over MRT-3, BusinessWorld, January 13, 2011

Further reading

- Allport, R. J. (1986). Appropriate mass transit for developing cities. Transport Reviews: A Transnational Transdisciplinary Journal, 6(4), 365–384. doi:10.1080/01441648608716636

- Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre (APERC). Institute of Energy Economics, Japan. (2008). Urban Transport Energy Use in the APEC Region – Benefits and Costs (PDF). Tokyo: Author. ISBN 978-4-931482-39-5.

- Dans, Jose P. Jr. (1990). "The Metro Manila LRT system: its future". In Institution of Civil Engineers. Rail Mass Transit Systems for Developing Countries. London: Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-1560-7.

- Midgley, Peter. (1994-03-31). Urban Transport in Asia : An Operational Agenda for the 1990s (World Bank technical paper no. 224). Washington D.C.: World Bank. ISBN 0-8213-2624-4.

- Thomson, J.M., R.J. Allport and P.R. Fouracre. (1990). "Rail mass transit in developing cities – the Transport and Road Research Laboratory study". In Institution of Civil Engineers. Rail Mass Transit Systems for Developing Countries. London: Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-1560-7.

- United States Agency for International Development. (June 2005). Integrated Environmental Strategies – Philippines Project Report – Metropolitan Manila. Author. (With United States Environmental Protection Agency, NREL, and the Manila Observatory).

- Uranza, Rogelio. (2002). The Role of Traffic Engineering and Management in Metro Manila. Workshop paper presented in the Regional Workshop: Transport Planning, Demand Management and Air Quality, February 2002, Manila, Philippines. Asian Development Bank (ADB).

- World Bank. (2001-05-23). "Project Appraisal Document for the Metro Manila Urban Transport Integration Project" (PDF). Author.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manila Light Rail Transit System. |

- Light Rail Transit Authority

- Facebook page of Philippine Railways

- Twitter page of Philippine Railways

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||