Manhua

| Manhua | |

|---|---|

|

Zhang Leping's Sanmao is one of the longest-running and most popular manhua series. Shown here is the first compilation published in 1936. | |

| Publishers | |

| Series | |

| Languages | Chinese |

| Related articles | |

| |

Manhua (simplified Chinese: 漫画; traditional Chinese: 漫畫; pinyin: Mànhuà) are Chinese comics produced in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Etymology

The word "manhua", literally "impromptu sketches", is originally an 18th-century term used in Chinese literati painting. It became popular in Japan as manga in the early 19th century. Feng Zikai, in his 1925 series of cartoons entitled Zikai Manhua, reintroduced the term into Chinese in the modern sense.[1]

History

.jpg)

The oldest surviving examples of Chinese drawings are stone reliefs from the 11th century BC and pottery from 5000 to 3000 B.C. Other examples include symbolic brush drawings from the Ming Dynasty, a satirical drawing titled "Peacocks" by the early Qing Dynasty artist Zhu Da, and a work called "Ghosts' Farce Pictures" from around 1771 by Luo Liang-feng. Chinese manhua was born in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, roughly during the years 1867 to 1927.[2]

The introduction of lithographic printing methods derived from the West was a critical step in expanding the art in the early 20th century. Beginning in the 1870s, satirical drawings appeared in newspapers and periodicals. By the 1920s palm-sized picture books like Lianhuanhua were popular in Shanghai.[3] They are considered the predecessor of modern day manhua.

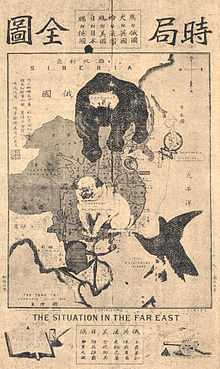

One of the first magazines of satirical cartoons came from the United Kingdom entitled The China Punch.[2] The first piece drawn by a person of Chinese nationality was The Situation in the Far East from Tse Tsan-tai in 1899, printed in Japan. Sun Yat-Sen established the Republic of China in 1911 using Hong Kong's manhua to circulate anti-Qing propaganda. Some of the manhua that mirrored the early struggles of the transitional political and war periods were The True Record and Renjian Pictorial.[2]

Up until the establishment of the Shanghai Sketch Society in 1927, all prior works were Lianhuanhua or loose collections of materials. The first successful manhua magazine, Shanghai Sketch (or Shanghai Manhua) appeared in 1928.[2] Between 1934 and 1937 about 17 manhua magazines were published in Shanghai. This format would once again be put to propaganda use with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. By the time the Japanese occupied Hong Kong in 1941, all manhua activities had stopped. With the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, political mayhem between Chinese Nationalists and Communists took place. One of the critical manhua, This Is a Cartoon Era by Renjian Huahui made note of the political backdrop at the time.[2]

One of the most popular and enduring comics of this period was Zhang Leping's Sanmao, first published in 1935.

The turmoil in China continued into the 50s and 60s. The rise of Chinese immigration turned Hong Kong into the main manhua-ready market, especially with the baby boom generation of children. The most influential manhua magazine for adults was the 1956 Cartoons World, which fueled the best-selling Uncle Choi. The availability of Japanese and Taiwanese comics challenged the local industry, selling at a pirated bargain price of 10 cents.[2] Manhua like Old Master Q were needed to revitalize the local industry.

The arrival of television in the 1970s was a changing point. Bruce Lee's films dominated the era and his popularity launched a new wave of Kung Fu manhua.[2] The explicit violence helped sell comic books, and the Government of Hong Kong intervened with the Indecent Publication Law in 1975.[2] Little Rascals was one of the pieces which absorbed all the social changes. The materials would also bloom in the 90s with work like McMug and three-part stories like "Teddy Boy", "Portland Street" and "Red Light District".[2]

Since the 1950s, Hong Kong's manhua market has been separate from that of mainland China.

Si loin et si proche, by Chinese writer and illustrator Xiao Bai, won the Gold Award at the 4th International Manga Award in 2011.[4][5] Several other manhua have also won the Silver and Bronze Awards at the International Manga Award.

Terminology

In 1925, the political work of Feng Zikai published a collection entitled Zi-Kai Manhua in Wenxue Zhoubao (Literature Weekly).[3] While the term "manhua" had existed before when borrowed from Japanese "manga", this particular publication took precedence over the many other description of cartoon arts that came before it.[2] As a result the term manhua became associated with Chinese comic materials. The Chinese characters for manhua are identical for those used in Japanese manga and Korean manhwa.

Categories

Before the official terminology was established, the art form were known by several names.[2]

| English | Pinyin | Chinese (traditional/simplified) |

|---|---|---|

| Allegorical Pictures | Rúyì Huà | 如意畫 / 如意画 |

| Satirical Pictures | Fĕngcì Huà | 諷刺畫 / 讽刺画 |

| Political Pictures | Zhèngzhì Huà | 政治畫 / 政治画 |

| Current Pictures | Shíshì Huà | 時事畫 / 时事画 |

| Reporting Pictures | Bàodǎo Huà | 報導畫 / 报导画 |

| Recording Pictures | Jìlù Huà | 紀錄畫 / 纪录画 |

| Amusement Pictures | Huáji Huà | 滑稽畫 / 滑稽画 |

| Comedy Pictures | Xiào Huà | 笑畫 / 笑画 |

Today's manhua are simply distinguished by four categories.

| English |

|---|

| Satirical and political manhua |

| Comical manhua |

| Action manhua |

| Children's manhua |

Characteristics

Modern Chinese-style manhua characteristics is credited to the breakthrough art work of the 1982 Chinese Hero.[2] It had innovative, realistic drawings with details resembling real people. Most manhua work from the 1800s to the 1930s contained characters that appeared serious. The cultural openness in Hong Kong brought the translation of American Disney characters like Mickey Mouse and Pinocchio in the 1950s, demonstrating western influence in local work like Little Angeli in 1954. The influx of translated Japanese manga of the 60s, as well as televised anime in Hong Kong also made a significant impression. Unlike manga, manhua comes in full color with some panels rendered entirely in painting for the single issue format.

See also

- List of manhua

- List of manhua publishers

- Lianhuanhua

- Hong Kong Comics

- Ani-Com Hong Kong

- Chinese animation

- Chinese art

- Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua

References

Inline citations

- ↑ Petersen, Robert S. (2011). Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313363306.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 Wong, Wendy Siuyi. [2002] (2001) Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua. Princeton Architectural Press, New York. ISBN 1-56898-269-0

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lent, John A. [2001] (2001) Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2471-7

- ↑ "Xiao Bai's Si loin et si proche Wins 4th Int'l Manga Award". Anime News Network. 2011-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- ↑ "The 4th International MANGA Award". manga-award.jp. International MANGA Award Executive Committee. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

General references

- Wai-ming Ng (2003). "Japanese Elements in Hong Kong Comics: History, Art, and Industry". International Journal of Comic Art. 5 (2):184–193.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||