Mandibular advancement splint

A mandibular splint or mandibular advancement splint (MAS) is a device worn in the mouth that is used to treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and snoring. These devices are also known as mandibular advancement devices, sleep apnea oral appliances, Oral Airway Dilators and sleep apnea mouth guards.

The splint treats snoring and sleep apnea by moving the lower jaw forward slightly, which tightens the soft tissue and muscles of the upper airway to prevent obstruction of the airway during sleep. The tightening created by the device also prevents the tissues of the upper airway from vibrating as air passes over them — the most common cause of loud snoring.

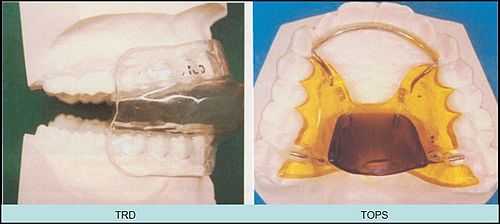

Mandibular advancement splints are widely used in the United States and are beginning to be used in the UK and Israel. Where appropriate, they are considered a good therapy choice as they are non-invasive, easily reversible, quiet, and generally well accepted by the patient. The focus of improvement in appliance design is in reducing bulk, permitting free jaw movement (permitting yawning, speaking, and drinking), and allowing the user to breathe through the mouth (early "welded gum shield"-type devices prevented oral breathing).

Evidence is accumulating to support the use of oral devices in the treatment of OSA, and studies demonstrating their efficacy have been underpinned by increasing recognition of the importance of upper airway anatomy in the pathophysiology of OSA.[1] Oral devices have been shown to have beneficial effects relating to several areas. These include the polysomnographic indexes of OSA, subjective and objective measures of sleepiness, blood pressure, aspects of neuropsychological functioning, and quality of life. Elucidation of the mechanism of action of oral devices has provided insight into the factors that predict treatment response and may improve the selection of patients for this treatment modality.[1] A further study by Dr. Edmund Rose, University of Freiburg, in 2004 successfully treated (apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) < 5) 88% of patients with MAS and proposes optimum patient selection to include AHI < 25, body mass index (BMI) < 30, and good dentition.[2]

A 2008 study published in Sleep on the influence of nasal resistance (NAR) on oral device treatment outcome in OSA demonstrates the need for an interdisciplinary approach between ENT surgeons and sleep physicians to treating OSA. The study suggests that higher levels of NAR may negatively affect outcome with MAS[3] and subsequently methods to lower nasal resistance may improve the outcome of oral device treatment.

A study of the effects of oral devices on blood pressure conducted by the Department of Respiratory and Sleep Medicine, Department of Nephrology, St. George Hospital, and the University of New South Wales in Australia found that oral devices were equally effective as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices in lowering the blood pressure of patients suffering from OSA.[4] The MDSA was clinically proven to conclusively show in a large and complex randomized controlled study that CPAP and MAS are effective in treating sleep-disordered breathing in subjects with AHI 5–30. Until recently CPAP was thought to be more effective, but randomised control evidence (such as that reviewed in 2013) suggests splints may be as effective in patients with a range of severities of obstructive sleep apnoea.[5] Both methods appear effective in alleviating symptoms, improving daytime sleepiness, quality of life and some aspects of neurobehavioral function, with CPAP usage being less than self-reported MAS usage. More test subjects and their domestic partners felt that CPAP was the most effective treatment, although MAS was easier to use. Nocturnal systemic hypertension was shown to improve with MAS but not CPAP, although the changes are small.[6]

Drawbacks

Some health plans may not cover mandibular advancement devices. Patients may pay upwards of $2000 out of pocket to secure these devices. Reportedly, these devices may also be somewhat uncomfortable, although many patients find them less bothersome than CPAP mask treatment. CPAP manufacturers claim that improperly fitted devices may cause teeth to shift over time, like with CPAP, but cite no evidence to support these claims.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-snore prostheses. |

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chan AS, Lee RW, Cistulli PA; Lee; Cistulli (August 2007). "Dental appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea". Chest 132 (2): 693–9. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2038. PMID 17699143.

- ↑ Rose E. (2004). "Identifying the Ideal Oral Appliance Candidate". Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics 65: 6.

- ↑ Zeng B; Ng AT; Qian J; Petocz P; Darendeliler MAS; Cistulli PA (2008). "Influence of nasal resistance on oral appliance treatment outcome in obstructive sleep apnea". Sleep 31 (4): 543–547.

- ↑ Gotsopoulos, H; Kelly, J. J.; Cistulli, P. A. (August 2004). "Oral appliance therapy reduces blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, controlled trial". Sleep 27 (5): 934–41. PMID 15453552.

- ↑ Phillips, C. L.; Grunstein, R. R.; Darendeliler, M. A.; Mihailidou, A. S.; Srinivasan, V. K.; Yee, B. J.; Marks, G. B.; Cistulli, P. A. (2013). "Health outcomes of continuous positive airway pressure versus oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 187 (8): 879–87. doi:10.1164/rccm.201212-2223OC. PMID 23413266.

- ↑ Barnes M, McEvoy RD, Banks S et al. (September 2004). "Efficacy of positive airway pressure and oral appliance in mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 170 (6): 656–64. doi:10.1164/rccm.200311-1571OC. PMID 15201136.