Malmquist bias

The Malmquist bias is an effect in observational astronomy which leads to the preferential detection of intrinsically bright objects. It was first described in 1922 by Swedish astronomer Gunnar Malmquist (1893–1982), who then greatly elaborated upon this work in 1925.[1][2] In statistics, this bias is referred to as a selection bias and affects the survey results in a brightness limited survey, where stars below a certain apparent brightness are not included. Since observed stars and galaxies appear dimmer when farther away, the brightness that is measured will fall off with distance until their brightness falls below the observational threshold. Objects which are more luminous, or intrinsically brighter, can be observed at a greater distance, creating a false trend of increasing intrinsic brightness, and other related quantities, with distance. This effect has led to many spurious claims in the field of astronomy. Properly correcting for these effects has become an area of great focus.

Understanding the bias

Magnitudes and brightness

In everyday life it is easy to see that light dims as it gets farther away. This can be seen with car headlights, candles, flashlights, and many other lit objects. This dimming follows the inverse square law, which states that the brightness of an object decreases as 1/d2, where d is the distance between the observer and the object.

Starlight also follows the inverse square law. Light rays leave the star in equal amounts in all directions. The light rays create a sphere of light surrounding the star. As time progresses, the sphere grows as the light rays travel through space away from the star. While the sphere of light grows, the number of light rays stays the same. So, the amount of light per unit of surface area of the sphere (called flux in astronomy) decreases with time. When observing a star, only the light rays that are in the given area being viewed can be detected. This is why a star appears dimmer the farther away it is.

If there are two stars with the same intrinsic brightness (called luminosity in astronomy), each at a different distance, the closer star will appear brighter while the further will appear dimmer. In astronomy, the apparent brightness of a star, or any other luminous object, is called the apparent magnitude. The apparent magnitude depends on the intrinsic brightness (also called absolute magnitude) of the object and its distance.

If all stars had the same luminosity, the distance from Earth to a particular star could be easily determined. However, stars have a wide range in luminosities. Therefore, it can be difficult to distinguish a very luminous star that is very far away from a less luminous star that is closer. This is why it is so hard to calculate the distance to astronomical objects.

Source of the Malmquist bias

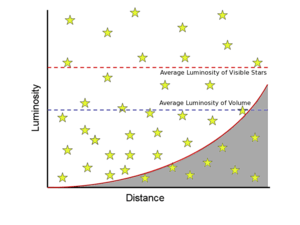

Typically, when looking at an area of sky filled with stars, only stars that are brighter than a limiting apparent magnitude can be seen. As discussed above, the very luminous stars that are farther away will be seen, as well as luminous and faint stars that are closer. There will appear to be more luminous objects within a certain distance from Earth than faint objects. However, there are many more faint stars,[3] they simply cannot be seen because they are so dim. The bias towards luminous stars when observing a patch of sky affects calculations of the average absolute magnitude and average distance to a group of stars. Because of the luminous stars that are at a further distance, it will appear as if our sample of stars is farther away than it actually is, and that each star is intrinsically brighter than it actually is. This effect is known as the Malmquist bias.[1]

When studying a sample of luminous objects, whether they be stars or galaxies, it is important to correct for the bias towards the more luminous objects. There are many different methods that can be used to correct for the Malmquist bias as discussed below.

The Malmquist bias is not limited to luminosities. It affects any observational quantity whose detectability diminishes with distance.[4]

Correction methods

The ideal situation is to somehow avoid this bias from entering a data survey. However, magnitude limited surveys are the simplest to perform, and other methods are difficult to put together, with their own uncertainties involved, and may be impossible for first observations of objects. As such, many different methods exist to attempt to correct the data, removing the bias and allowing the survey to be usable. The methods are presented in order of increasing difficulty, but also increasing accuracy and effectiveness.

Limiting the sample

The simplest method of correction is to only use the non-biased portions of the data set, if any, and throw away the rest of the data.[5] Depending on the limiting magnitude selected, there may be a range of distances in the data set over which all objects of any possible absolute magnitude could be seen. As such, this small subset of data should be free of the Malmquist bias. This is easily accomplished by cutting off the data at the edge of where the lowest absolute magnitude objects would be hitting the limiting magnitude. Unfortunately, this method would waste a great deal of good data, and would limit the analysis to nearby objects only, making it less than desirable. (Looking at the figure to the right, only the first fifth of the data in distance could be kept before a data point is lost to the bias.) Of course, this method assumes that distances are known with relatively good accuracy, which as mentioned before, is a difficult process in astronomy.

Traditional correction

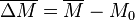

The first solution, proposed by Malmquist in his 1922 work, was to correct the calculated average absolute magnitude ( ) of the sample back to the true average absolute magnitude (M0).[1] The correction would be

) of the sample back to the true average absolute magnitude (M0).[1] The correction would be

To calculate the bias correction, Malmquist, and others following this method follow six main assumptions:[6]

- There exists no interstellar absorption, or that the stuff in space between stars (like gas and dust) is not affecting the light and absorbing parts of it. This assumes that the brightness is simply following the inverse square law, mentioned above.

- The luminosity function (Φ) is independent of the distance (r). This basically just means that the universe is the same everywhere, and that stars will be similarly distributed somewhere else as they are here.

- For a given area on the sky, or more specifically the celestial sphere, the spatial density of stars (ρ) depends only on distance. This assumes that there are the same number of stars in each direction, on average.

- There is completeness, meaning the sample is complete and nothing is missed, to an apparent magnitude limit (mlim).

- The luminosity function can be approximated as a Gaussian function, centered on an intrinsic mean absolute magnitude M0.

- Stars are of the same spectral type, with intrinsic mean absolute magnitude M0 and dispersion σ.

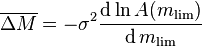

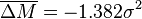

Obviously, this is a very ideal situation, with the final assumption being particularly troubling, but allows for an approximate correction of simple form. By integrating the luminosity function over all distances and all magnitudes brighter than mlim,

where A(mlim) is the total number of stars brighter than mlim. If the spatial distribution of stars can be assumed to be homogeneous, this relation is simplified even further, to the generally accepted form of

Multiple-band observation corrections

The traditional method assumes that the measurements of apparent magnitude and the measurements from which distance is determined are from the same band, or predefined range, of wavelengths (e.g. the H band, a range of infrared wavelengths from roughly about 1300–2000 nanometers), and this leads to the correction form of cσ2, where c is some constant. Unfortunately, this is rarely the case, as many samples of objects are selected from one wavelength band but the distance is calculated from another. For example, astronomers frequently select galaxies from B-band catalogs, which are the most complete, and use these B band magnitudes, but the distances for the galaxies are calculated using the Tully–Fisher relation and the H band. When this happens, the square of the variance is replaced by the covariance between the scatter in the distance measurements and in the galaxy selection property (e.g. magnitude).[7]

Volume weighting

Another fairly straightforward correction method is to use a weighted mean to properly account for the relative contributions at each magnitude. Since the objects at different absolute magnitudes can be seen out to different distances, each point's contribution to the average absolute magnitude or to the luminosity function can be weighted by 1/Vmax, where Vmax is the maximum volume over which the objects could have been seen. Brighter objects (that is, objects with smaller absolute magnitudes) will have a larger volume over which they could have been detected, before falling under the threshold, and thus will be given less weight through this method since these bright objects will be more fully sampled.[8] The maximum volume can be approximated as a sphere with radius found from the distance modulus, using the object’s absolute magnitude and the limiting apparent magnitude.

However, there are two major complications to calculating Vmax. First is the completeness of the area covered in the sky, which is the percentage of the sky that the objects were taken from.[8] A full sky survey would collect objects from the entire sphere, 4π steradians, of sky but this is usually impractical, both from time constraints and geographical limitations (ground based telescopes can only see a limited amount of sky due to the Earth being in the way). Instead, astronomers will generally look at a small patch or area of sky and then infer universal distributions by assuming that space is either isotropic, that it is generally the same in every direction, or is following a known distribution, such as that one will see more stars by looking toward the center of a galaxy than by looking directly away. Generally, the volume can be simply scaled down by the percentage actually viewed, giving the correct number of objects to volume relation. This effect could potentially be ignored in a single sample, all from the same survey, as the objects will basically all be altered by the same numerical factor, but it is incredibly important to account for in order to be able to compare between different surveys with different sky coverage.

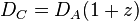

The second complication is cosmological concerns of redshift and the expanding universe, which must be considered when looking at distant objects. In these cases, the quantity of interest is the comoving distance, which is a constant distance between two objects assuming that they are moving away from each other solely with the expansion of the universe, known as the Hubble flow. In effect, this comoving distance is the object's separation if the universe's expansion were neglected, and it can be easily related to the actual distance by accounting for how it would have expanded. The comoving distance can be used to calculate the respective comoving volume as usual, or a relation between the actual and comoving volumes can also be easily established. If z is the objects redshift, relating to how far emitted light is shifted toward longer wavelengths as a result of the object moving away from us with the universal expansion, DA and VA are the actual distance and volume (or what would be measured today) and DC and VC are the comoving distance and volumes of interest, then

A large downside of the volume weighting method is its sensitivity to large-scale structures, or parts of the universe with more or less objects than average, such as a star cluster or a void.[10] Having very overdense or underdense regions of objects will cause an inferred change in our average absolute magnitude and luminosity function, according with the structure. This is a particular issue with the faint objects in calculating a luminosity function, as their smaller maximum volume means that a large-scale structure therein will have a large impact. Brighter objects with large maximum volumes will tend to average out and approach the correct value in spite of some large-scale structures.

Advanced methods

Many more methods exist which become increasingly complicated and powerful in application. A few of the most common are summarized here, with more specific information found in the references.

Stepwise maximum likelihood method

This method is based on the distribution functions of objects (such as stars or galaxies), which is a relation of how many objects are expected with certain intrinsic brightnesses, distances, or other fundamental values. Each of these values have their own distribution function which can be combined with a random number generator to create a theoretical sample of stars. This method takes the distribution function of distances as a known, definite quantity, and then allows the distribution function of absolute magnitudes to change. In this way, it can check different distribution functions of the absolute magnitudes against the actual distribution of detected objects, and find the relation that provides the maximum probability of recreating the same set of objects. By starting with the detected, biased distribution of objects and the appropriate limits to detection, this method recreates the true distribution function. However, this method requires heavy calculations and generally relies on computer programs.[10][11]

Schechter estimators

Paul Schechter found a very interesting relation between the logarithm of a spectral line's line width and its apparent magnitude, when working with galaxies.[12] In an perfect, stationary case, spectral lines should be incredibly narrow bumps, looking like lines, but motions of the object such as rotation or motion in our line of sight will cause shifts and broadening of these lines. The relation is found by starting with the Tully–Fisher relation, wherein the distance to a galaxy is related to its apparent magnitude and its velocity width, or the 'maximum' speed of its rotation curve. From macroscopic Doppler broadening, the logarithm of the line width of an observed spectral line can be related to the width of the velocity distribution. If the distances are assumed to be known very well, then the absolute magnitude and the line width are closely related.[12] For example, working with the commonly used 21cm line, an important line relating to neutral hydrogen, the relation is generally calibrated with a linear regression and given the form

where P is log(line width) and α and β are constants.

The reason that this estimator is useful is that the inverse regression line is actually unaffected by the Malmquist bias, so long as the selection effects are only based on magnitude. As such, the expected value of P given M will be unbiased and will give an unbiased log distance estimator. This estimator has many properties and ramifications which can make it a very useful tool.[13]

Complex mathematical relations

Advanced versions of the traditional correction mentioned above can be found in the literature, limiting or changing the initial assumptions to suit the appropriate author's needs. Often, these other methods will provide very complicated mathematical expressions with very powerful but specific applications. For example, work by Luri et al. found a relation for the bias for stars in a galaxy which relates the correction to the variance of the sample and the apparent magnitude, absolute magnitude, and the height above the galactic disk. This gave a much more exact and accurate result, but also required an assumption about the spatial distribution of stars in the desired galaxy.[14] While useful individually, and there are many examples published, these have very limited scope and are not generally as broadly applicable as the other methods mentioned above.

Applications

Anytime a magnitude-limited sample is used, one of the methods described above should be used to correct for the Malmquist bias. For instance, when trying to obtain a luminosity function, calibrate the Tully–Fisher relation, or obtain the value of the Hubble constant, the Malmquist bias can strongly change the results.

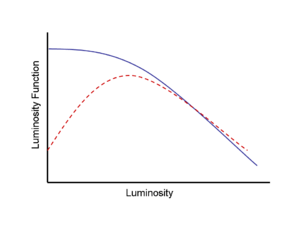

The luminosity function gives the number of stars or galaxies per luminosity or absolute magnitude bin. When using a magnitude-limited sample, the number of faint objects is underrepresented as discussed above. This shifts the peak of the luminosity function from the faint end to a brighter luminosity and changes the shape of the luminosity function. Typically, the volume weighting method is used to correct the Malmquist bias so that the survey is equivalent to a distance-limited survey rather than a magnitude-limited survey.[15] The figure to the right shows two luminosity functions for an example population of stars that is magnitude-limited. The dashed luminosity function shows the effect of the Malmquist bias, while the solid line shows the corrected luminosity function. Malmquist bias drastically changes the shape of the luminosity function.

Another application that is affected by the Malmquist bias is the Tully–Fisher relation, which relates the luminosity of spiral galaxies to their respective velocity width. If a nearby cluster of galaxies is used to calibrate the Tully–Fisher relation, and then that relation is applied to a distant cluster, the distance to the farther cluster will be systematically underestimated.[13] By underestimating the distance to clusters, anything found using those clusters will be incorrect; for example, when finding the value of the Hubble constant.

These are just a few examples where the Malmquist bias can strongly affect results. As mentioned above, anytime a magnitude-limited sample is used, the Malmquist bias needs to be corrected for. A correction is not limited to just the examples above.

Alternatives

Some alternatives do exist to attempt to avoid the Malmquist bias, or to approach it in a different way, with a few of the more common ones summarized below.

Distance-limited sampling

One ideal method to avoid the Malmquist bias is to only select objects within a set distance, and have no limiting magnitude but instead observe all objects within this volume.[5] Clearly, in this case, the Malmquist bias is not an issue as the volume will be fully populated and any distribution or luminosity function will be appropriately sampled. Unfortunately, this method is not always practical. Finding distances to astronomical objects is very difficult, and even with the aid of objects with easily determined distances, called standard candles, and similar things, there are great uncertainties. Further, distances are not generally known for objects until after they have already been observed and analyzed, and so a distance limited survey is usually only an option for a second round of observations, and not initially available. Finally, distance limited surveys are generally only possible over small volumes where the distances are reliably known, and thus it is not practical for large surveys.

Homogeneous and inhomogeneous Malmquist correction

This method attempts to correct the bias again, but through very different means. Rather than trying to fix the absolute magnitudes, this method takes the distances to the objects as being the random variables and attempts to rescale those.[13] In effect, rather than giving the stars in the sample the correct distribution of absolute magnitudes (and average absolute magnitude), it attempts to 'move' the stars such that they would have a correct distribution of distances. Ideally, this should have the same end result as the magnitude correction methods and should result in a correctly represented sample. In either the homogeneous or inhomogeneous case, the bias is defined in terms of a prior distribution of distances, the distance estimator, and the likelihood function of these two being the same distribution. The homogeneous case is much simpler and rescales the raw distance estimates by a constant factor. Unfortunately, this will be very insensitive to large scale structures such as clustering as well as observational selection effects, and will not give a very accurate result. The inhomogeneous case attempts to correct this by creating a more complicated prior distribution of objects by taking into account structures seen in the observed distribution. In both cases though, it is assumed that the probability density function is Gaussian with constant variance and a mean of the true average log distance, which is far from accurate. However, this method is debated and may not be accurate in any implementation due to uncertainties in calculating the raw, observed distance estimates causing the assumptions to use this method to be invalid.[13]

Historical alternatives

The term 'Malmquist bias' has not always been definitively used to refer to the bias outlined above. As recently as the year 2000, the Malmquist bias has appeared in the literature clearly referring to different types of bias and statistical effect.[16] The most common of these other uses is to refer to an effect that takes place with a magnitude limited sample, but in this case the low absolute magnitude objects are overrepresented. In a sample with a magnitude limit, there will be a margin of error near that boundary where objects that should be bright enough to make the cut are excluded and objects that are slightly below the limit are instead included. Since low absolute magnitude objects are more common than brighter ones, and since these dimmer galaxies are more likely to be below the cutoff line and scattered up, while the brighter ones are more likely to be above the line and scattered down, an over-representation of the lower luminosity objects result. However, in modern day literature and consensus, the Malmquist bias refers to the effect outlined above.

Further reading

- Galactic Astronomy, James Binney & Michael Merrifield (1998); pages 111–115. Strict derivation of the Malmquist bias.[17]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Malmquist, Gunnar (1922). Jour. Medd. Lund Astron. Obs. Ser. II. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Malmquist, Gunnar (1925). "A Contribution to the Problem of Determining the Distribution in Space of the Stars". Ark Mat Astr Fys Bd.

- ↑ Salpeter, Edwin (1955). "The luminosity function and stellar evolution". ApJ 121: 161. Bibcode:1955ApJ...121..161S. doi:10.1086/145971.

- ↑ Wall, J. V.; Jenkins, C. R. (2012). Practical Statistics for Astronomers. Cambridge Observing Handbooks for Research Astronomers (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-521-73249-9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sandage, Allan (November 2000). "Malmquist Bias and Completeness Limits". In Murdin, P. The Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Bristol: Institute of Physics Publishing. Article 1940. Bibcode:2000eaa..bookE1940S. doi:10.1888/0333750888/1940. ISBN 0-333-75088-8.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Butkevich, A. G.; Berdyugin, A. V.; Terrikorpi, P. (Sep 2005). "Statistical biases in stellar astronomy: the Malmquist bias revisited". MNRAS 362 (1): 321–330. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.362..321B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09306.x.

- ↑ Gould, Andrew (Aug 1993). "Selection, Covariance, and Malmquist Bias". The Astrophysical Journal 412: 55–58. Bibcode:1993ApJ...412L..55G. doi:10.1086/186939.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Blanton, Michael; Schlegel, D.J.; Strauss, M.A.; Brinkmann, J.; Finkbeiner, D.; Fukugita, M.; Gunn, J.E.; Hogg, D.W. et al. (June 2005). "New York University Value-Added Galaxy Catalog: A Galaxy Catalog Based on New Public Surveys". The Astronomical Journal 129 (6): 2562–2578. arXiv:astro-ph/0410166. Bibcode:2005AJ....129.2562B. doi:10.1086/429803.

- ↑ Hogg, David W. (Dec 2000). "Distance measures in cosmology". Astro-ph. arXiv:astro-ph/9905116.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Blanton, Michael R.; Lupton, R.H.; Schlegel, D.J.; Strauss, M.A.; Brinkmann, J.; Fukugita, M.; Loveday, J. (Sep 2005). "The Properties and Luminosity Function of Extremely Low Luminosity Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal 631 (1): 208–230. arXiv:astro-ph/0410164. Bibcode:2005ApJ...631..208B. doi:10.1086/431416.

- ↑ Efstathiou, George; Frenk, C.S.; White, S.D.M.; Davis, M. (Dec 1988). "Gravitational clustering from scale-free initial conditions". MNRAS 235: 715–748. Bibcode:1988MNRAS.235..715E.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Schechter, P.L. (July 1980). "Mass-to-light ratios for elliptical galaxies". Astronomical Journal 85: 801–811. Bibcode:1980AJ.....85..801S. doi:10.1086/112742.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Hendry, M.A.; Simmons, J.F.L.; Newsam, A.M. (Oct 1993). "What Do We Mean by 'Malmquist Bias'?". Astro-ph. arXiv:astro-ph/9310028. Bibcode:1993cvf..conf...23H.

- ↑ Luri, X.; Mennessier, M.O.; Torra, J.; Figueras, F. (Jan 1993). "A new approach to the Malmquist bias". Astronomy and Astrophysics 267: 305–307. Bibcode:1993A&A...267..305L.

- ↑ Binney, James; Merrifield, Michael (1998). Galactic Astronomy. Princeton University Press. pp. 111–115.

- ↑ Murdin, Paul (2000). "Malmquist, Gunnar (1893–1982)". Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Bibcode:2000eaa..bookE3837. doi:10.1888/0333750888/3837. ISBN 0-333-75088-8.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ James Binney & Michael Merrifield (1998). Galactic Astronomy.