Malatily Bathhouse

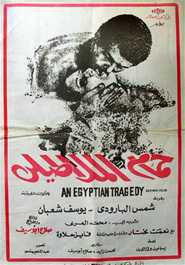

Malaṯily Bathhouse (Arabic: حمام الملاطيلي "Ĥamam al-Malaṯily") is a 1973 Egyptian film directed by Salah Abu Seif. The main actors are Shams al-Baroudi and Yusuf Shåban. It is adapted from a novel by Ismåeel Walieddin. Samar Habib, author of Female Homosexuality in the Middle East: Histories and Representations, said "that the title of the film can "be easily translated" as Malatily Bathhouse."[1] The opening credits of the film have the English title An Egyptian Tragedy. Habib said that it was "strangely translated" into An Egyptian Tragedy.[1]

Plot

The beginning shows what Habib calls a "long scenic tribute" to Cairo and to the general city.[1] Habib said that the director "visually implies the polymorphous vagaries of the city in which an immoral underworld is bound to flourish.[2]

The main character, Aĥmad, leaves rural eastern Egypt for the city hoping to become economically self-sufficient, get an apartment for his parents, and obtain a law degree. He and his family are refugees from a town occupied by the Israeli army, Ismaåilia. Ali, the owner of the Malatily Bathhouse, offers to let him stay there for free. Aĥmad encounters several characters there, including Naåeema, a prostitute who he becomes obsessed with, and Raouf, a male homosexual. Ali later has Aĥmad work as his accountant. Aĥmad eventually has sexual intercourse with Naåeema. Aĥmad finds a lack of employment opportunities and becomes associated with the bathhouse, so his original goals are not met.[3]

Habib said "There appears to be a sensitive awareness that foreign viewers of the film should not regard its content as conspiring with or approving of the morally loose behaviour of the libertines it depicts."[1] Habib argues that this seems to depict Egyptian society in a "state of disarray" likely to be occurring during the Suez Crisis.[3]

Cast and characters

Aĥmad is the main character.

One character, Raouf Bey, is a male homosexual. Habib said that Raouf "subverts popular understanding of homosexuality by being unable to be brought back into the norm of heterosexual desires."[1] Raouf makes advances towards Aĥmad, who initially cannot comprehend them. He is good friends with Åli.[3] Habib wrote that Raouf is "an unsympathetic character" as he exploits men who do not willingly do homosexual acts but require him in order to make a living, and that Raouf's sexuality "initially appears" to be without emotion and only physical.[4] Habib wrote that it appears Raouf wishes to prostitute Aĥmad but in fact he truly wants Aĥmad to be his boyfriend,[5] and while citing the works of the historian Jabarti he laments that he cannot do what he wants in the modern society despite the freedom of the past.[6]

Muålim Åli is the owner of the bathhouse. He gives male prostitutes to Raouf.[3] Police arrest him after Kamal commits murder.[4]

Naåeema, a female prostitute, has her first romantic sexual relation with Ahmad.[4] She comes from a poor background and prostitutes herself in order to support herself.[3]

Kamal, a male prostitute,[3] is an employee of Åli. He murders a casino director who Habib implies is a "sugar daddy" and who is the new employer of Kamal.[4] Habib wrote that the male prostitutes are "incidental to the main plot" and all originate from desperate, impoverished backgrounds.[3]

Samir is a male prostitute. Aĥmad tells him he should find a reliable job that has respectability, and Samir responds stating that he is poor and does not have the luxury of planning for the far future.[4] Through Samir and Fatĥi, Ahmad learns that some people cannot go ahead in life through perseverance, self-education, and diligence, and that some people have to be prostitutes in order to survive.[6]

Fatĥi is another male prostitute.[3] In a conversation with Aĥmad he tells him a concept similar to that given by Samir.[6]

Mohsin is an employee of the bathhouse.[4]

See also

References

- Habib, Samar. Female Homosexuality in the Middle East: Histories and Representations. Routledge, July 18, 2007. ISBN 0415956730, 9780415956734.